ART-TRIBUTE:MoMA-Transmissions 1960–80

If great distances separate the imagined geographies of Eastern Europe and Latin America, resonances between artists working there can also be found. Both regions have strong constructivist traditions, and both developed a variety of alternative models for art production and circulation post 1945 precipitated by their respective political situations (Soviet control in Eastern Europe and populist or dictatorial regimes in Latin America). While the revolutionary spirit of 1968 expressed itself very differently in each of these regions, between 1960 and 1980 artists forged relationships across distances, transmitting their artistic ideas and political beliefs through travel, mail, publications and word-of-mouth. Many of the artists worked outside the official institutional frameworks of their home countries and some of their production didn’t necessarily have the status of art at the time, which poses many challenges to collecting and exhibiting it today.

If great distances separate the imagined geographies of Eastern Europe and Latin America, resonances between artists working there can also be found. Both regions have strong constructivist traditions, and both developed a variety of alternative models for art production and circulation post 1945 precipitated by their respective political situations (Soviet control in Eastern Europe and populist or dictatorial regimes in Latin America). While the revolutionary spirit of 1968 expressed itself very differently in each of these regions, between 1960 and 1980 artists forged relationships across distances, transmitting their artistic ideas and political beliefs through travel, mail, publications and word-of-mouth. Many of the artists worked outside the official institutional frameworks of their home countries and some of their production didn’t necessarily have the status of art at the time, which poses many challenges to collecting and exhibiting it today.

By Dimitris Lempesis

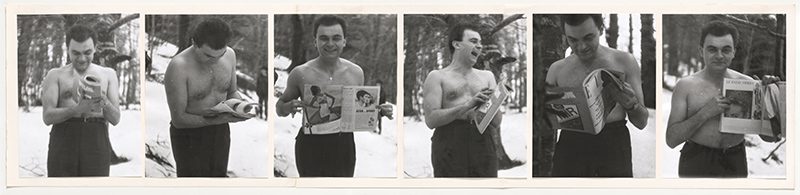

Photo: MoMA Archive

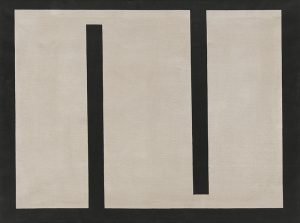

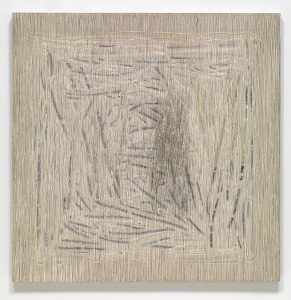

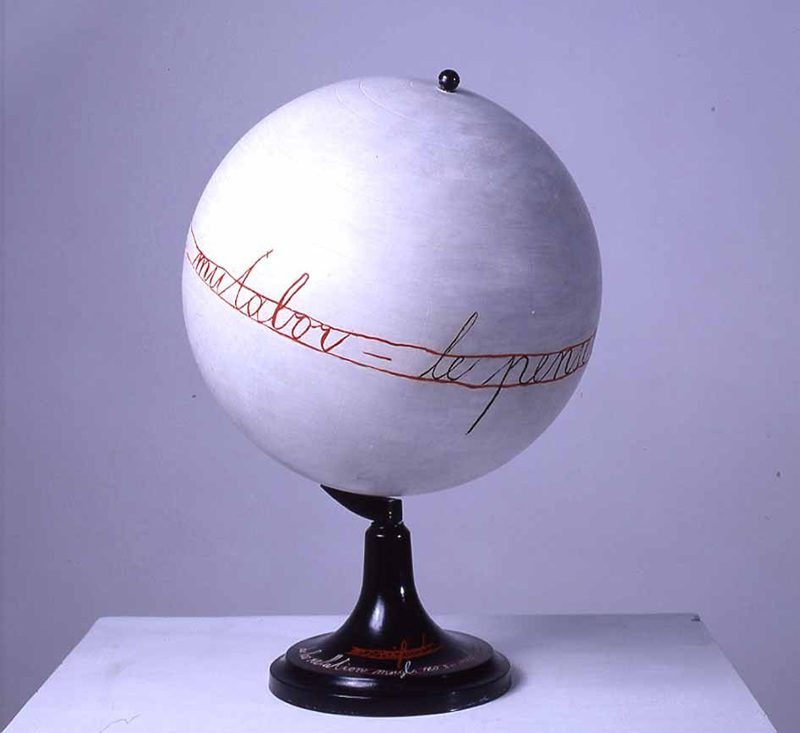

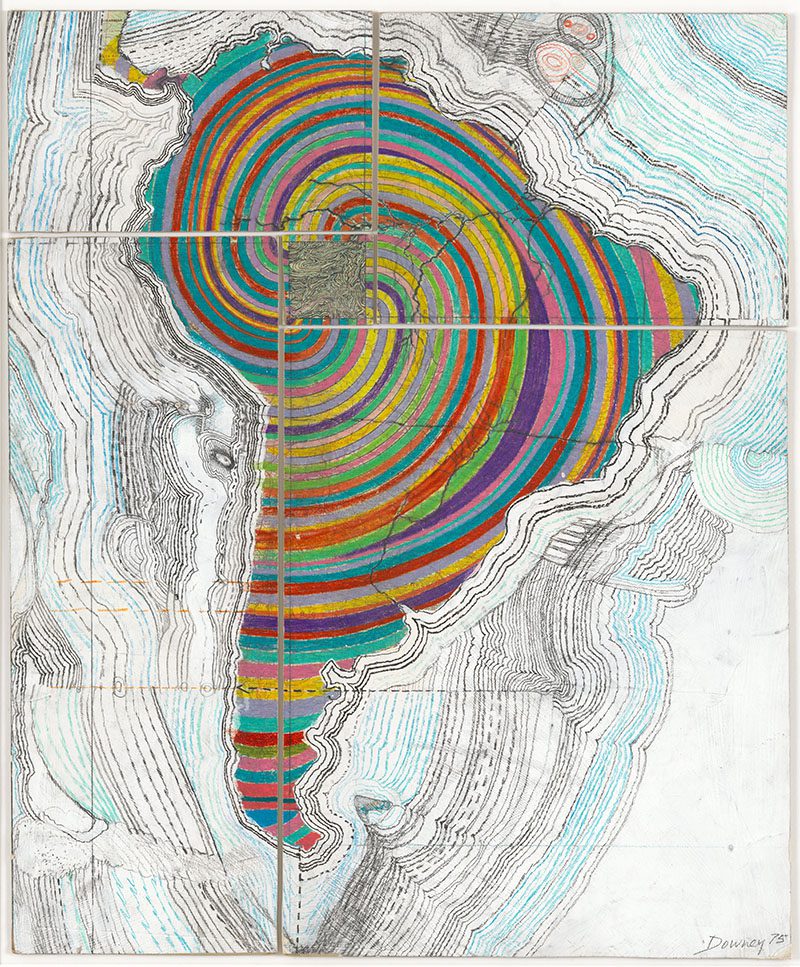

The exhibition “Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980” focuses on parallels and connections among artists active in Latin America and Eastern Europe in the ‘60s and ‘70s. During these decades, which flanked the widespread student protests of 1968, artists working in distinct political and economic contexts, from Prague to Buenos Aires, developed cross-cultural networks to circulate their artworks and ideas. The exhibition opens with a reconsideration of an international group of artists, including: Willys de Castro, Julije Knifer and Julio Le Parc, as well as Lucio Fontana, François Morellet , Victor Vasarely and Ellsworth Kelly among others, who were featured in the influential exhibition “Art Abstrait Constructif International”, which took place at Denise René Gallery in Paris from Dec. 1961 to Feb. 1962. These artists’ engagement with practices from geometric abstract paintings to kinetic light installations based on predetermined systems prepared a path from the abstract vocabularies of prewar modernism to an experience of art in constant flux, probing the roles of the artist, the spectator, and the institution. One major transformation across Latin American and Eastern European art scenes in the ‘60s and ‘70s was the embrace of anti-institutional gestures. This skepticism toward authority, including that of art itself, emphasized creative production outside a market context. The second section brings together several anti-art groups such as: Gorgona, Aktual, OHO, El techo della ballena and Fluxus East. These loose-knit collectives of independent-minded artists began operating outside “Official” cultural policies by engaging with process-directed exercises, games, gatherings, walks, alternative music, and concrete poetry. A section centers on a community of artists, including: Oscar Bony, David Lamelas, Lea Lublin and Marta Minujín, who confronted the aesthetic and political implications of mass media communication, including film, television, and the telex, during a vibrant, experimental period of technological innovation and political tension. Clustered around the influential Instituto Torcuato Di Tella an epicenter for avant-garde art production in Buenos Aires, these artists’ political engagement emerged from their experiences of repression under the regime of General Juan Carlos Onganía, as well as news from New York, Paris, and Vietnam. Another section is devoted to the conceptual links forged in the late ‘60s and ‘70s between the work of Edward Krasiński, Daniel Buren, André Cadere and Henryk Stażewski, who challenged the definition of art, the ways of looking at it, and even the spaces where one would encounter it. Staging unofficial, itinerant “exhibitions” that ran parallel with licensed programming, all four artists shared an interest in minimalist sculptural gestures and interventionist artistic strategies. The eruptive force of 1968, followed by social unrest flaring across the globe and the second-wave feminist movement, led to the expansion of art into political life and praxis, presenting a new generation of activist, performance, and video pioneers, including: Marina Abramović, VALIE EXPORT, Sanja Iveković, Ana Mendieta and Ewa Partum, who produced works of cross-cultural reference with a critical eye to the visual depictions of women in official culture. In the 1970s artists began increasingly to relocate their work to public spaces, aiming to further test the boundaries between art and life and challenge the prescribed positions of artist and spectator. Braco’s Dimitrijević multiyear project “Casual Passersby I Met At” consisted of oversized photographic portraits of anonymous people that he displayed on billboards around the city of Zagreb and in public squares previously reserved for images of Marshal Tito and high-ranking party officials. Similarly, in the radicalized climate of Prague after the 1968 Soviet reoccupation of Czechoslovakia, during a period of forced “Normalization” by the Soviet military, Jiří Kovanda, found meaning in barely perceptible yet politically disruptive gestures that were illegal under Soviet rule, such as in ”Contact” (1979), when the artist walked around Prague casually and gently touching passersby. Also included in this section are the street actions of the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte, a Chilean activist group of artists, sociologists, and poets who used strategies of theatricality and performance to challenge the Pinochet dictatorship. The parallel developments and individual achievements of artists working collaboratively such as: Luis Camnitzer, Liliana Porter, Geta Brătescu, Ion Gigorescu, Běla Kolářová, Jiří Kolář, Waltercio Caldas, Leandro Katz and Dóra Maurer. While clearly connected to a system of global debates, these Conceptual artists employed diverse strategies grounded in the newfound agency of photography and film, in the sway of countercultural activities, and in direct response to events of political significance. While artists found rigor and formal clarity in their often-concise conceptual conceits, their agenda extended beyond the narrow confines of art to an allegorical understanding of political commentary. In reaction to the increasing dominance of American Pop art and the realities of expansive media culture around the world, a section considers aspects of popular art in Latin America that critiqued images associated with state representation. The inflated proportions of Marisol’s (Marisol Escobar), iconic sculpture “Love”, instills a sense of deadpan humor and devastating critique in the form of a Coca-Cola bottle thrust deep into a woman’s mouth. Throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s Beatriz Gonzalez explored subject matters specific to her native Colombia’s history and vernacular culture. A parallel section highlights the exceptional production in Eastern Europe and Latin America of posters made for cultural events in film, theater, music, art festivals, and political events, as well as in commercial design and advertising. The exhibition concludes with a section centered on the video installation “Video Trans Americas” (1976), by Juan Downey, which is a rich intertextual investigation of the self through the lens of historical Western art and culture and the rituals of Downey’s native Latin America. The work is an odyssey of Downey’s life among indigenous peoples of South America. The artist’s encounters with otherness function as a metaphor for understanding his own cultural identity, which is central to the exhibition’s thesis of possible counter-geographies, realignments, alternative models of solidarity, and ways of rethinking the historical narratives of postwar art.

Info: Curators: Stuart Comer, Roxana Marcoci &Christian Rattemeyer, Curatorial Assistants: Giampaolo Bianconi & Martha Joseph, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 11 West 53 Street, New York, Duration: 5/11/15-3/1/16, Days & Hours: Sun-Thu 10:30-17:30, Fri 10:30-20:00, www.moma.org