PRESENTATION: Worldbuilding-Gaming and Art in the Digital Age

The aesthetics of games entered artistic practice decades ago, when artists began to integrate, modify, and subvert the visual language of video games to address issues of our existence within virtual worlds. Some artists have also brought to light a critique of games from within the system itself. Recently, artists have begun to harness the mainstream power of gaming to communicate new forms of engagement that reach the massive audience of this borderless global industry.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Julia Stoschek Collection Archive

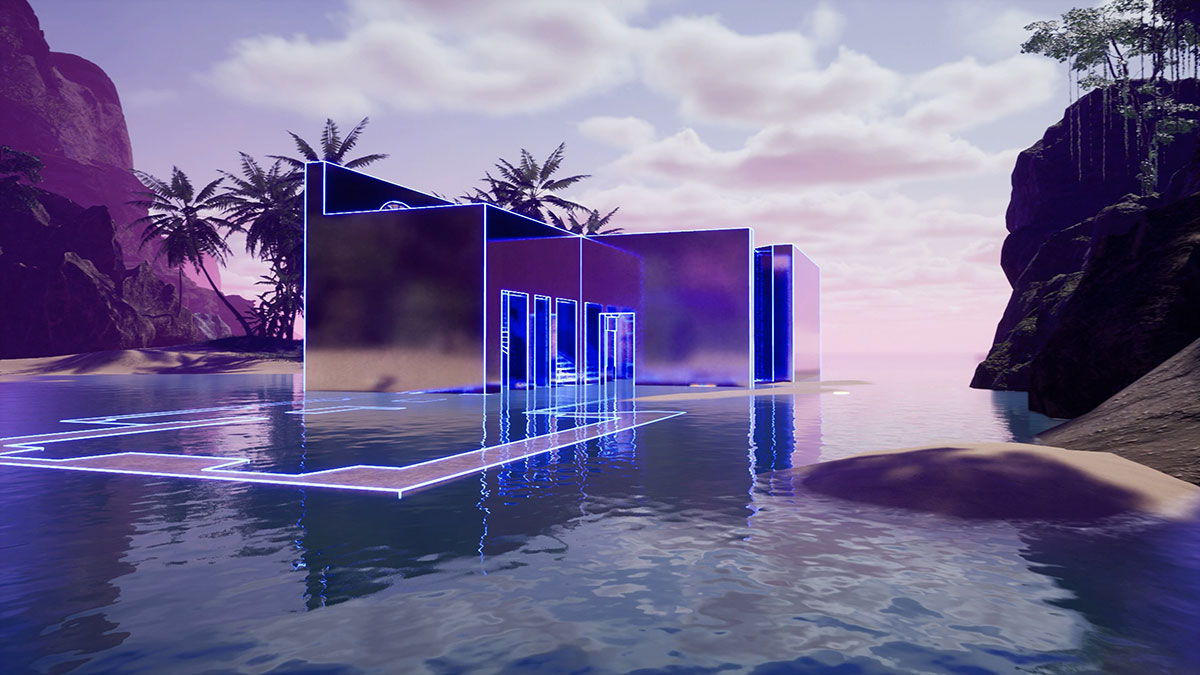

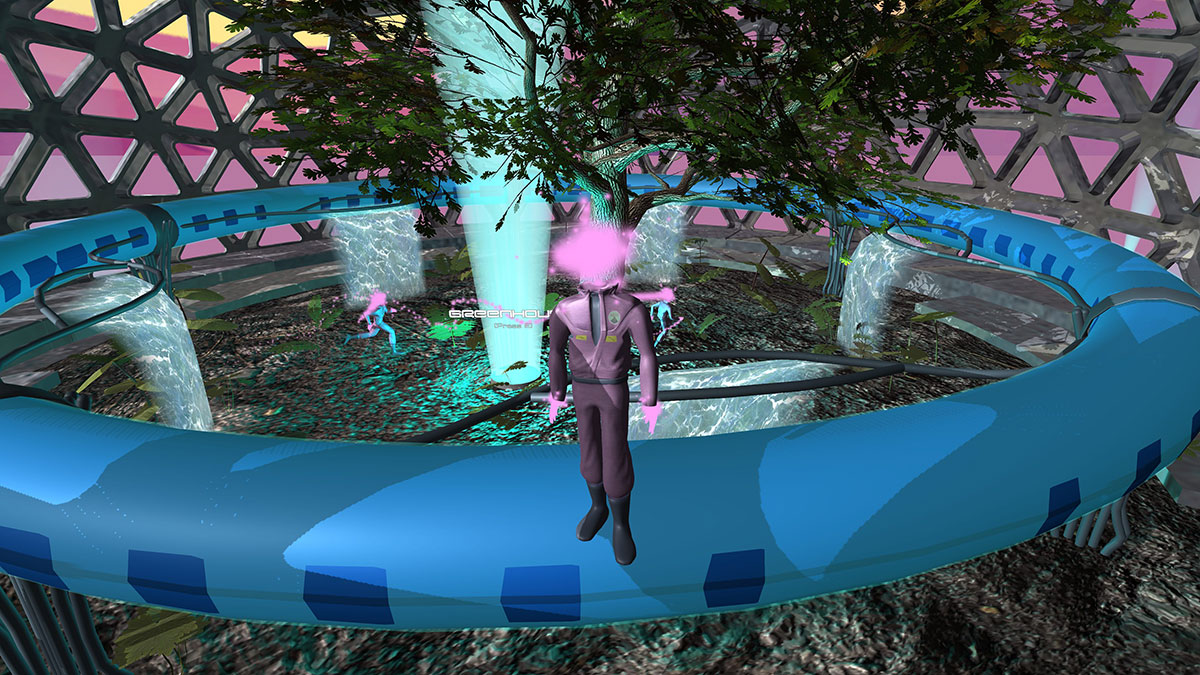

The exhibition “WORLDBUILDING: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age” examines the relationship between gaming and time-based media art with a journey through various ways in which artists have interacted with video games and made them into an art form. From single-channel video works to site-specific, immersive, and interactive environments, the exhibition encompasses over thirty artworks from the mid-1990s to the present. Works from the Julia Stoschek Collection, some of them especially adapted for the exhibition, are joined by newly commissioned works. Including video, virtual reality (VR), artificial intelligence (AI), and game-based works, most of the works are interactive and openly invite visitors to immerse themselves in the multitude of alternative realities created by artists, spanning past, present, and future. The “Jirry Tribe Stop” (2021) by Basmah Felemban is an elaborate cosmography that is experienced as an interactive game. The work is the artist’s most comprehensive worldbuilding venture to date and is developed around stories she has scripted as a foundation for a new (simulated) world with its own logic, language, and order. Formally, the work is composed of surrealistic tempered abstractions. Semiotically, the rhythmic array of shapes, colors, and imagery form a complex sys-tem of signification developed by Felemban over a two-year period and programmed in collaboration with a team of 3D artists and game designers. Theo Triantafyllidis creates a range of works that reference simulation, gaming, and NFT (non-fungible token) aesthetics in his studio practice. Trained as an architect in Athens, Triantafyllidis began working with digital art communities while practicing architecture in Beijing. The pervasive influence of his training is evident in the immersive environments he creates, and the strong sense of spatial awareness is connected to the scenes he generates with virtual tools. In Triantafyllidis’s “Pastoral” (2019), a three-dimensional work for VR (virtual reality) and installation, players find themselves situated in the middle of an expansive virtual hayfield in a video game–like envi-ronment. Using a game controller or common game navigation keys on the keyboard, the players control the body of the central character, a hyper-bodied, hybrid-gendered Orc character wearing a bikini. The excessively muscular figure, which also serves as Triantafyllidis’s avatar in other works, is unlike Orcs depicted in popular culture. In other fictional scenarios, Orcs tend toward the monstrous and violent—tough hunters with a keen sense of smell, out to kill. They are featured prominently in online fantasy games such as the mas-sively multiplayer online role-playing game World of Warcraft. But Triantafyllidis’s Orc is nearly nude, brushing its way through the rus-tling waist-high hayfield in a bikini, positioned to explore and search the bucolic and bountiful field.

In the digital game/mobile app “Salaam” (2016–ongoing) developed by Lual Mayen everybody is able to experience how to survive escaping from a war zone while helping people actually living in refugee camps. Players take on the role of a person fleeing a war zone. In order to survive, they must evade enemies attempting to shoot or capture them. They also have to obtain sufficient food, water, and medical supplies. The game employs mechanisms familiar from dig-ital running games such as a depleting energy bar and the need to source provisions. The subject of fleeing turns Salaam into a “serious game,” not only serving to entertain, but also playfully and purposefully conveying the skills and knowledge that bring the communities of the players and refugees together. Players develop an empathy for refugees, becoming responsible for the actions of their avatars, which places them in a more active role than merely reading or watching films about the issue. In Salaam, Mayen has developed a new category of serious games that he termed “gaming for good.” The virtuous cause involves the gamers paying in real terms for the needs of their figures in the game; for all the resources they purchase money flows via an app directly to NGOs that are involved in humanitarian work in refugee camps. “Bathing, Climbing, Falling, Sitting, Sleeping, and Swimming” (2015) is a series of animations that follow the avatar of artist Ed Fornieles , a fox hijacked into static-soaked worlds. As the protagonist swims through surveillance footage, his anxieties are entangled in a web of pixels. Climbing data mountains and corporate junk feeds, he is overwhelmed by a series of abstract challenges. These simulations reflect the ways in which we express emotional states through digital appendages. In the face of quandaries, the artist’s proposition is cunningly simple: become your avatar. A digital ethnographer, Ed Fornieles is known for social perfor-mances that appropriate gaming structures. His immersive instal-lations, films, and sculptures investigate the nuances of self-repre-sentation in an era of virtuality. Fornieles’s practice draws on what curator Paul Luckraft has aptly termed “emotional supply chains”—the fabrication of the self in digital environments, through the supply of complex emotions and experiences. This term originates from psychoanalyst Otto Fenichel’s 1938 idea of “narcissistic supply,” namely the requirement of narcissists to have a constant supply of admi-ration from their environments. As virtual spaces increasingly map social worlds, the emotional supplies that we require to maintain our identities are multiple and demanding. Affect is the chief commodity of such cultures, a powerful tool to gain capital. In his participato-ry works, Fornieles establishes temporary social structures through which alternative forms of intimacy can emerge.

Ed Atkins uses 3D computer-generated moving images and its aesthetics, situated between seductive hyperreality and lifeless arti-ficiality, to express the (im)possibility of emotions in the digital. His disembodied avatars eerily approach the human by imitating powerful emotions. Yet, they frequently remain stuck in the digital, their awkward, jerky movements reminiscent of figures in platform games. Entirely generated in 3D software, Atkins’s works reflect the intricate relations between human and machine through the ever-evolving stylistic devices of the gaming and film industries. In the video collage “Even Pricks” (2013), virtual tracking shots through templates from After Effects are advertised by exploding title sequences as if they were part of a game preview. Whether shards of glass, snowflakes, flames, or water, Atkins integrates a range of simulations that simulate the singularity of a situation. However, similar to the high-resolution renderings of skin, hair, and fingernails, such simulations often appear overly slick and perfect. Texture, materiality, and the corporeal continue to challenge the cinema and advertising industry’s skills in creating illusion, disrupting any immersive experience. The career of KAWS (Brian Donnelly) has been marked by his ability to cross disciplines’ boundaries and push our conceptions of what an artist, artwork, exhibition, collector, and audience can be. Within the Pop Art tradition, he has created a prolific body of influential work, which both engages young people with contemporary art and straddles the worlds of art and design to include street art, graphic and product design, paintings, murals, and large-scale sculptures. The exhibition presents a video documentation of “NEW FICTION” (2022), the Serpentine Galleries’ multilayered global project with KAWS, developed in collaboration with Acute Art and the globally popular online video game Fortnite. For his exhibition “NEW FICTION”, KAWS presented new and recent works in physical and augmented reality at Serpentine Galleries. A virtual recreation of the show was launched simultaneously in Fortnite, allowing mil-lions of players from all over the world to experience the exhibition from anywhere. All built by the Fortnite Creative Community, play-ers were able to explore the Serpentine’s grounds and experience KAWS’s artworks and his iconic sculptures in a completely new way. The video shown in the exhibition is a documentation of a gameplay: viewers can watch the player’s avatar moving through KAWS’s virtual exhibition in Fortnite.

Participating Artists: Larry Achiampong & David Blandy, Peggy Ahwesh, Rebecca Allen, Cory Arcangel, Ed Atkins, LaTurbo Avedon, Balenciaga, Meriem Bennani, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Cao Fei, Ian Cheng, Harun Farocki, Basmah Felemban, Ed Fornieles, Sarah Friend, The Institute of Queer Ecology, JODI, Rindon Johnson, KAWS, Keiken, Kim Heecheon, Lawrence Lek, LuYang, Gabriel Massan, Lual Mayen, Sondra Perry, Jacolby Satterwhite, Frances Stark, Jakob Kudsk Steensen, STURTEVANT, Transmoderna, Suzanne Treister, Theo Triantafyllidis, Angela Washko, Thomas Webb

Photo: Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), 2018–2019, artificial lifeform, infinite duration, color, sound, dimensions variable. Video still. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels/Seoul/Los Angeles and Pilar Corrias, London

Info: Curator: Hans Ulrich Obrist, Julia Stoschek Collection, Schanzenstrasse 54, Düsseldorf, Germany, Duration: 5/6-10/12/2022, Days & Hours: Sun 11:00-18:00, www.jsc.art/