PREVIEW: Nobuyoshi Araki

Fascinated by the fundamental and inextricable triangle of sex, life, and death (it is to him we owe the words “I was no sooner out of my mother’s womb than I turned around and photographed her vagina”), Nobuyoshi Araki is tireless as a photographer, obsessed by women, often bound, and flowers, captured in the all the intimacy of their colored folds.

Fascinated by the fundamental and inextricable triangle of sex, life, and death (it is to him we owe the words “I was no sooner out of my mother’s womb than I turned around and photographed her vagina”), Nobuyoshi Araki is tireless as a photographer, obsessed by women, often bound, and flowers, captured in the all the intimacy of their colored folds.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Hamiltons Gallery Archive

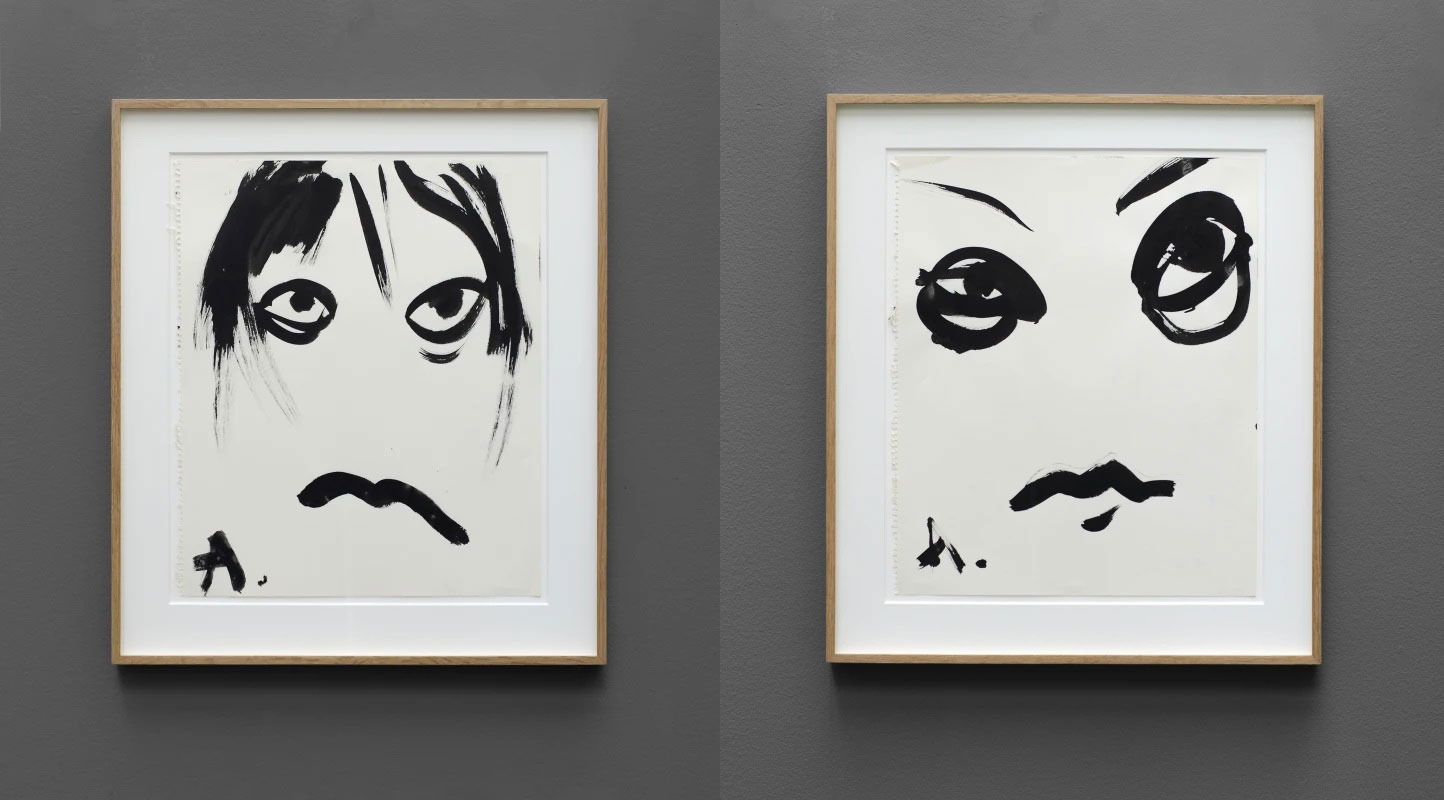

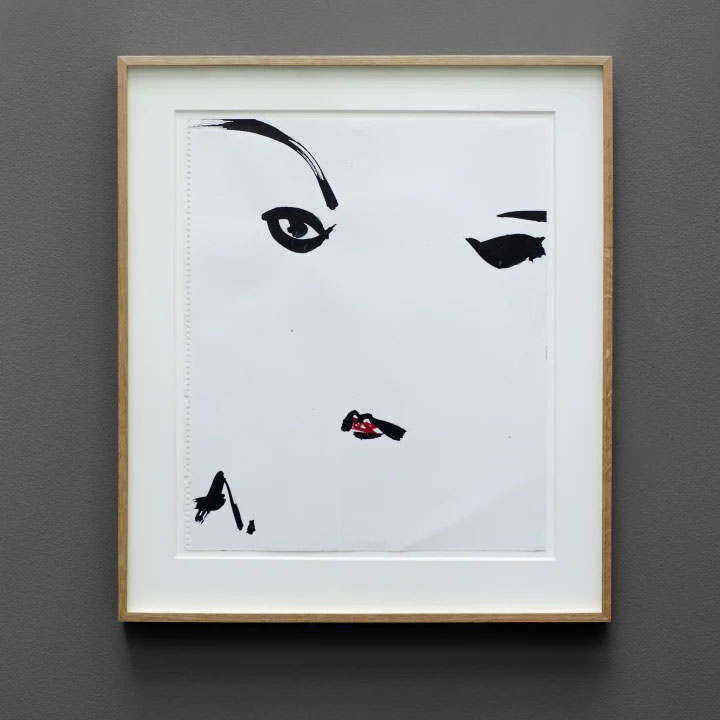

Nobuyoshi Araki presents a series of rare, unique sumi ink drawings, these unseen artworks will be presented alongside a series of well-known photographs from the artist’s career. Nobuyoshi Araki is one of Japan’s most renowned photographers and contemporary artists. Araki’s work is often controversial, but his artistic genius is undeniable; every image reveals extreme technical mastery which influences many creative fields, including photography, film, painting, and in this case, ink drawing. Araki’s inspiration for these expressive ink drawings derives from his regular jaunts in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district at a bar named Hanaguruma, which translates to ‘Flower Carriage’. The artist spent many nights in Hanaguruma, where he would sketch portraits, photograph, drink and generally hang out into the late hours. The tiny bar, which closed its doors in 2015, consisted of a simple counter and two seats, and was frequented by an array of visual artists and peformers from Nan Goldin, Robert Frank to Bjork and Lady Gaga. Those who visited were encouraged to make their mark on the walls with signatures, drawings, and Polaroids. The portraits that Araki created in Hanaguruma were made using sumi ink which is an ancient monochrome ink derived of specific soot, ground with water and gelatine, used for calligraphy and painting. The technique of sumi ink drawing first developed in Japan around the mid-14th Century and is the embodiment of Japanese aesthetics. Using a simply made, natural black ink often applied to handmade paper, the artists are able to capture a timeless beauty and complexity of the natural world. The focus of the art of ink drawing or sumi-e has since its inception has been on the quality of the line, the goal of sumi drawing is not to accurately represent a subject but instead to convey a general sentiment or feeling of it. The bold or subtle use of brushstrokes allowed sumi artists to eliminate from their paintings all but the essential character of their subject. This is clear in Araki’s portraits from Hanaguruma; his lightning- quick sketches barley trace the outline of his subjects’ faces, sometimes with vibrant accents such as a blaze of red lips or the outline of an eye. The confidence with which Araki illustrates his sitters allows the viewer to imagine sitting next to him in Hanaguruma as his brush flashes across his sketchbook capturing the essence of everyone around him.

From 1959-1963, Nobuyoshi Araki studied photography and filmmaking at Chiba university, Tokyo. His influences were Italian Neo-Realist and French NouvelleVague-Films; his favourite directors, Cari Theodor Dreyer and Robert Bresson. In 1963, he graduated from the Department of Engineering at Chiba University; majored in Photography and Film Making. After college he went on to work at Dentsu Advertising. Along with company’s official work, he used the equipments for his own work as well. He won The Sun Magazine’s photo contest for Satchin in 1964. In 1965, Nobuyoshi Araki had his first one-man show at Shinjuku Station Building. He published two books, “Gemi” and “Gemi the Whore”. Both these works were thought to be lost but were recovered and published as Jeanne in 1997. He compiled his all artworks in 25 volumes, printing 70 copies each in 1970 and distributing them to his friends, art critics and random people. He calls this year “The First Year of Araki”. In same year April, he held an exhibition called “Sur-sentimentalist No. 2: The Truth about Carmen Marie”. The artworks were enlargement of the singer’s genitals. Likewise, similar show was held at a noodle shop, which was exhibited until 1976. Araki distanced himself from photojournalism in the 1970s and turned towards nudes: scandalous large photos of vaginas, shot in effective black-and-white. His erotic photos exist not as a self-contained group but interact with his other work groups. As part of a series the nudes correspond with the flower photographies, architectural images and sky- and landscapes. He sees the themes city, woman and nature as metaphors for sexuality, birth, life and death. “To talk about death is the real taboo today”, Araki says and describes a leitmotif of his work: the connection of eros and death. In 1971, he married Yoko Araki and released a book that consists of photos taken while the couple went to honeymoon, this book was published as “Sentimental Journey”. In 1974, he helped found the Workshop School of Photography in collaboration with Shōmei Tōmatsu and Daido Moriyama. He opened Araki Private Photo School with about ten students in 1976. Nobuyoshi Araki started working for the magazine New Self. In 1977, he started publishing two series in Weekend Super magazine, Actresses and Pseudo-Reportage. He later created further series’ like “A Sentimental Journey in Pursuit of Women”, a photo novel, stills about the stunning views of Tokyo, Girlfriends and more. From 1980, he worked as a still photographer for films and recitals. Later he produced his first film, “High School Girl Fake Diary” in 1981. He began shooting stills for Japan edition of PlayBoy and Camera Mainichi though he was asked to discontinue this work in 1981. Araki published “Nostalgic Nights” as a wedding anniversary gift to Yoko in 1984. These stills were inspired by Andrei Tarkovsky’s film “Nostalghia”. These images were published as “Love Life” in 1985. He held a slide show at Cinema Rise in 1986, it was about Araki’s neighborhood, his studio, hotels and nude women. In 1987, he created Hokeited Nichijo in collaboration with Yoko. Araki’s wife Yoko aged 42, passed away on 27th January 1990. That year, he was awarded with Annual Award of the Photographic Society of Japan. Later on, A Pep Rally for Araki was held. He also participated in NHK-TV’s program The Future of Photography. In 1991, Araki published “Winter Journey”, in memory of his wife. The photos were taken during Yoko’s hospitalization and funeral. Araki received the Domestic Photographer’s Award at the 7th Hishikawa International Photo Festival. He was requested to photograph cover for Icelandic musician Björk’s 1997 remix album. He has also photographed Lady Gaga. Since their meeting in 2001, Kaori has appeared in thousands of photographs. In image after image, like a Japanese Scheherazade, this Tokyo muse seems to be reconciling to life a man wounded by the death of his beloved wife Yōko, the photographs are printed both in stark black-and-white and in lush colour. More recently, Araki has been adding hand-painted elements to some of these portraits. The effect is a Kaori captured by a rainbow. In his notorious bondage photographs, Araki shows women bound by tight ropes, trussed-up and helpless, often dangling precariously above the floor. “It’s not a punishment. It’s an expression of affection”, says Araki, “In Japan, it’s called kinbaku and it’s not the same thing as the Western notion of bondage. For me, when the girl is tied up, she gets more sexy, more beautiful”. His hand-painted photographs of Kaori show her imprisoned by waves of paint instead, tossed around naked in a swirling maelstrom of colour. In many images, Kaori wear’s a traditional kimono, partly open to reveal her pale skin in contrast with the boldly patterned fabric. The stylisation echoes the graphic art of erotic 19th Century Japanese wood-block prints. At the same time, Araki nods to the high brow with the low brow. The elaborate, symbolic poses of Kabuki theatre and Noh drama, clash with the trash culture of cheap sex and Godzilla. With a knowing glance, Kaori clasps plastic dinosaurs in her hands. Reclining provocatively on a bed, the toy monster peeks into the folds in her kimono. In 2005, Travis Klose produced a documentary film, “Arakimentari”, on life and work of Nobuyoshi Araki. His work has been exhibited at Tate and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art(SFMOMA). He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2008 and has undergone a surgery successfully. In the same year, he was awarded with Austrian Decoration for Science and Art. Araki’s newest series, “Flower Cemetery” are Still Life photographs of flower arrangements haunted by disused, children’s dolls, toys and plastic figures. Focusing his lens on cut flowers, a source of intense but temporary beauty, the artist reflects on mortality. Populated by ungainly plastic figures in scenes that are both humorous and disquieting, these images can be read as a method of deflected self-portraiture.

Photo: Nobuyoshi Araki, Mad Old Man 76th Birthday, 2016, © Nobuyoshi Araki, Courtesy the artist and Hamiltons Gallery

Info: Hamiltons Gallery, 13 Carlos Place, London, United Kingdom, Duration: 3/5-10/6/2022, Days & Hours: Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat 11:00-16:00, www.hamiltonsgallery.com/

Right: Nobuyoshi Araki, Hanaguruma 3, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Sumi Ink on Sketchbook Paper, Unique, © Nobuyoshi Araki, Courtesy the artist and Hamiltons Gallery

Right: Nobuyoshi Araki, Hanaguruma 14, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Sumi Ink on Sketchbook Paper, Unique, © Nobuyoshi Araki, Courtesy the artist and Hamiltons Gallery