PRESENTATION: León Ferrari-Amiable Cruelty

![León Ferrari, La civilización occidental y cristiana (Western Christian Civilization) [detail], 1965. Assemblage, © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/000-3.jpg)

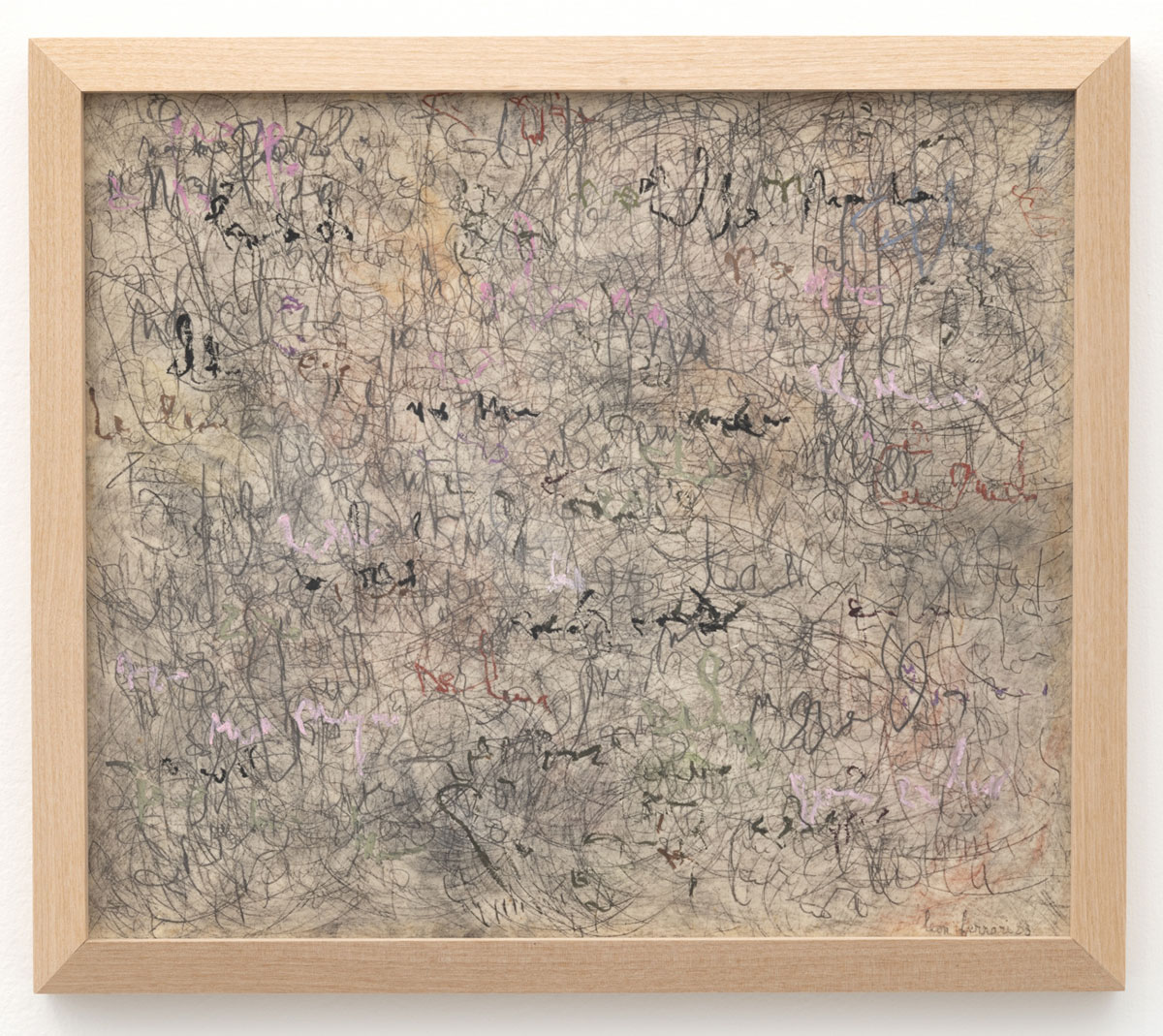

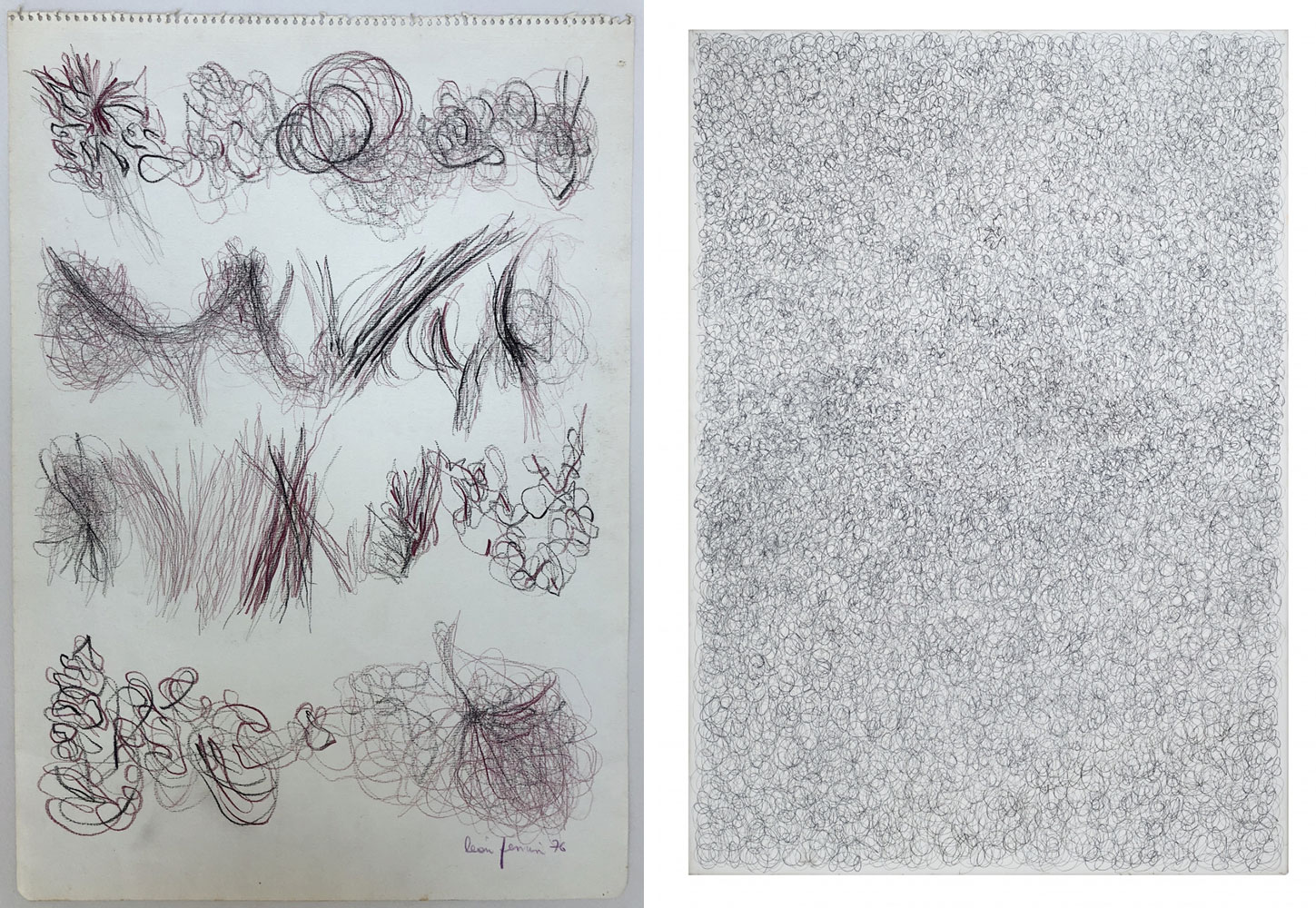

Despite being one of the most influential artists of his generation in Latin America, León Ferrari is surprisingly little known across Europe. Having initially trained as an electrical engineer, he would pursue an artistic career purely by chance in the 1950s. Returning to Buenos Aires in 1955, he would diversify his sculpting practices by delving into new artistic creations in cement, plaster, and wood, as well as wire from the 1960s. It was not until 1962 that Ferrari conceived his first works on paper. From 1963, words and calligraphy found a home in his repertoire. In 1976, Ferrari fled the Argentine dictatorship, self-exiled in Brazil for 15 years. He began exploring new artistic practices, such as mail art, photocopying, lithography, and even artist books.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Centre Pompidou Archive

The Centre Pompidou presents “Amiable Cruelty” the very first museum exhibition of Léon Ferrari’s work in France. Léon Ferrari is the creator of a protean, alternately mysterious and literal body of work whose formal rigour is on a par with his subversive power. An engineer by profession, León Ferrari began practicing as a self-taught artist in the 1950s in Rome, where he made his first terracotta sculptures. From then on, his work developed in a process of continuous metamorphosis. He explored various materials, from the plaster and cement, wood and wire, in his sculptures, to the diverse pigments and inks in his drawings. He introduced conceptual strategies to his work by linking drawing with writing in his “written visual art” and he experimented with thinking in images through the use of collage. After the military coup in Argentina, he lived in exile from 1976 to 1991 in São Paulo, Brazil. There he made his large-format sculptures, explored serialization by working with engravings, photocopies, and heliographies, and continued his confrontations with forms of political and religious power. His work as an artist is inseparable from his lifelong commitment to various political causes, especially in defense of human rights. His work was included in the 1999 exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s at the Queens Museum of Art in New York, and in Heterotopías. Medio siglo sin lugar: 1918–1968 at the Museo Reina Sofía in 2000. These exhibitions can be considered milestones in the internationalization of his work, which reached a high point in 2007 when he was awarded the Golden Lion at the 52nd Venice Biennale. León Ferrari’s multifaceted and challenging oeuvre resists a linear reading and traditional artistic categorizations. His complex production can be seen as a pendulum moving between the decodification of violence and playful exploration at the limits of meaning. Despite its apparent heterogeneity, his work maintains an organicism and musicality within series that are repeated, reformulated, superimposed, and allowed to contaminate one another, touching on the social and political issues to which he was committed throughout his life. Rather than conceiving of art as a restricted practice aimed at an elite, from the outset Ferrari was dedicated to the idea of an “art of meanings” (the title of one of his 1968 essays, “Arte de los significados”) based on an aesthetic-political experimentation that would have the social significance necessary to engage a broad public. In fact, in the 1960s Ferrari was a key figure in the politicization of the avant-garde artists who broke away from the Instituto Di Tella, the emblematic institution that fostered experimentation in Argentine art during that decade. This rift began to open with the exhibition Homenaje al Viet-Nam (Homage to Vietnam, 1966) and reached its high point with Tucumán arde (Tucumán Burns, 1968). Ferrari was also a link between the political radicalization of Argentine art and the regional debates on art and revolution that took place in the early 1970s at the Encuentro de artistas plásticos latinoamericanos (Encounter of Latin American Visual Artists) group shows in Chile and Cuba, countries then experimenting with the construction of socialist societies on the American continent.

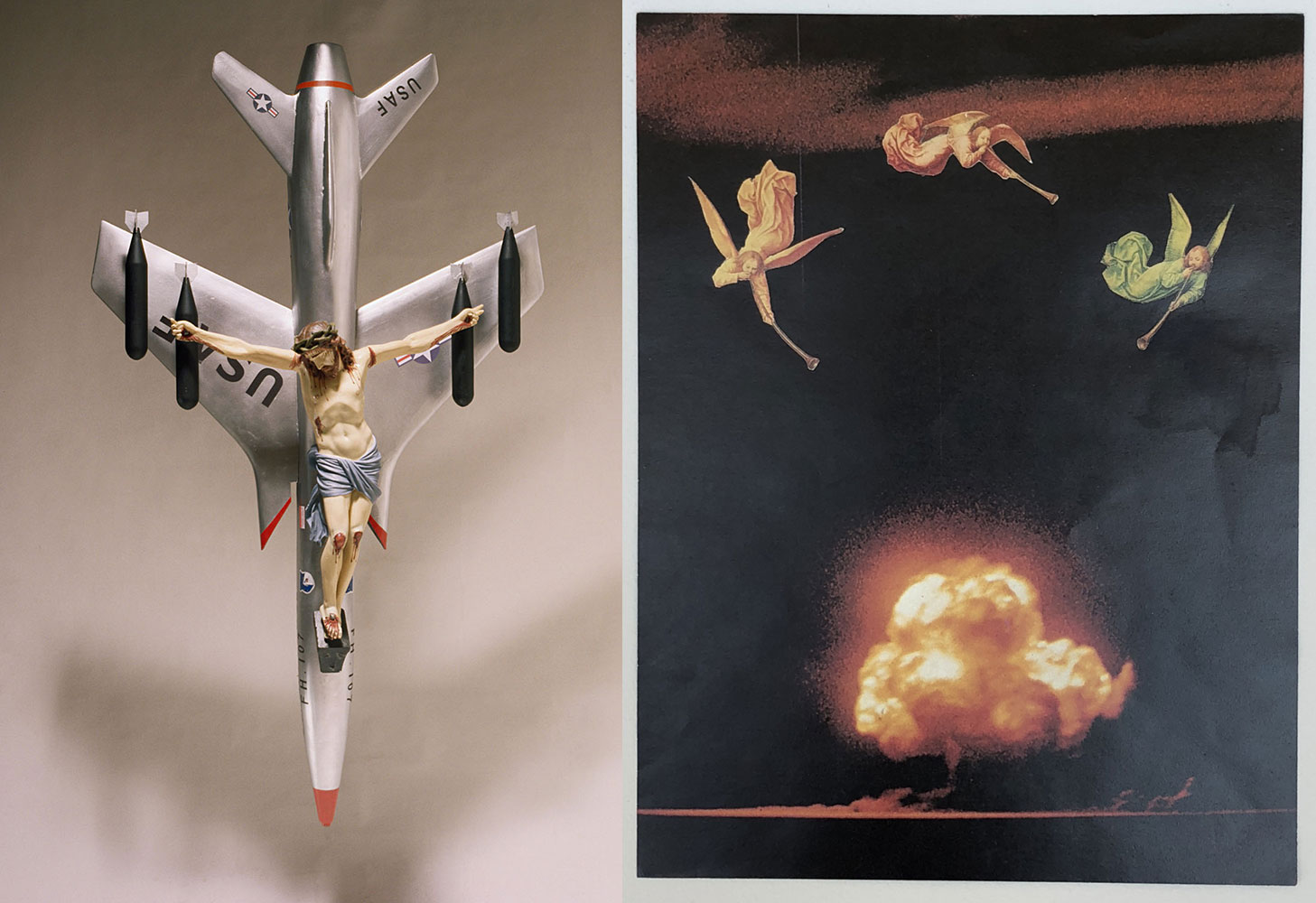

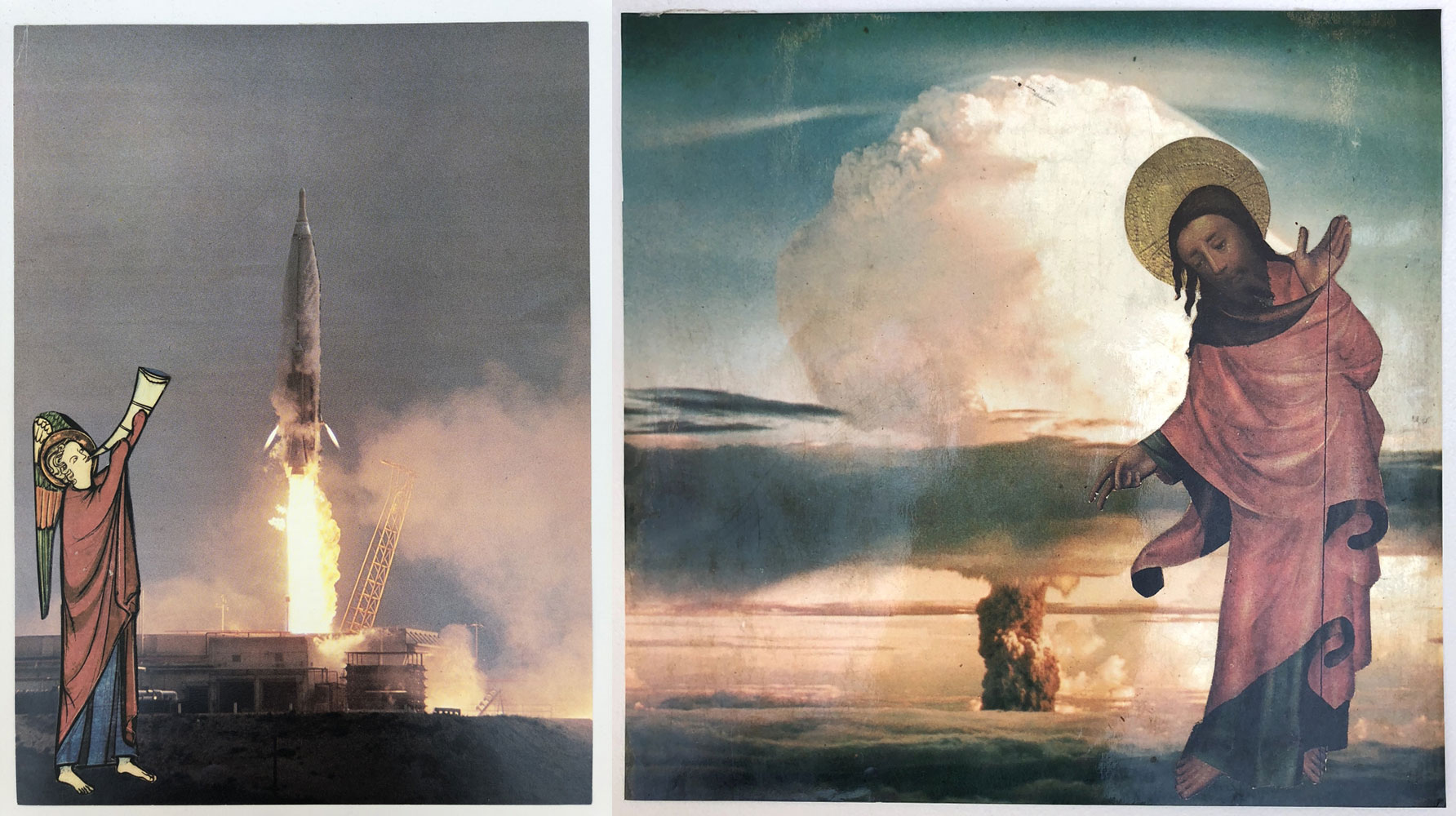

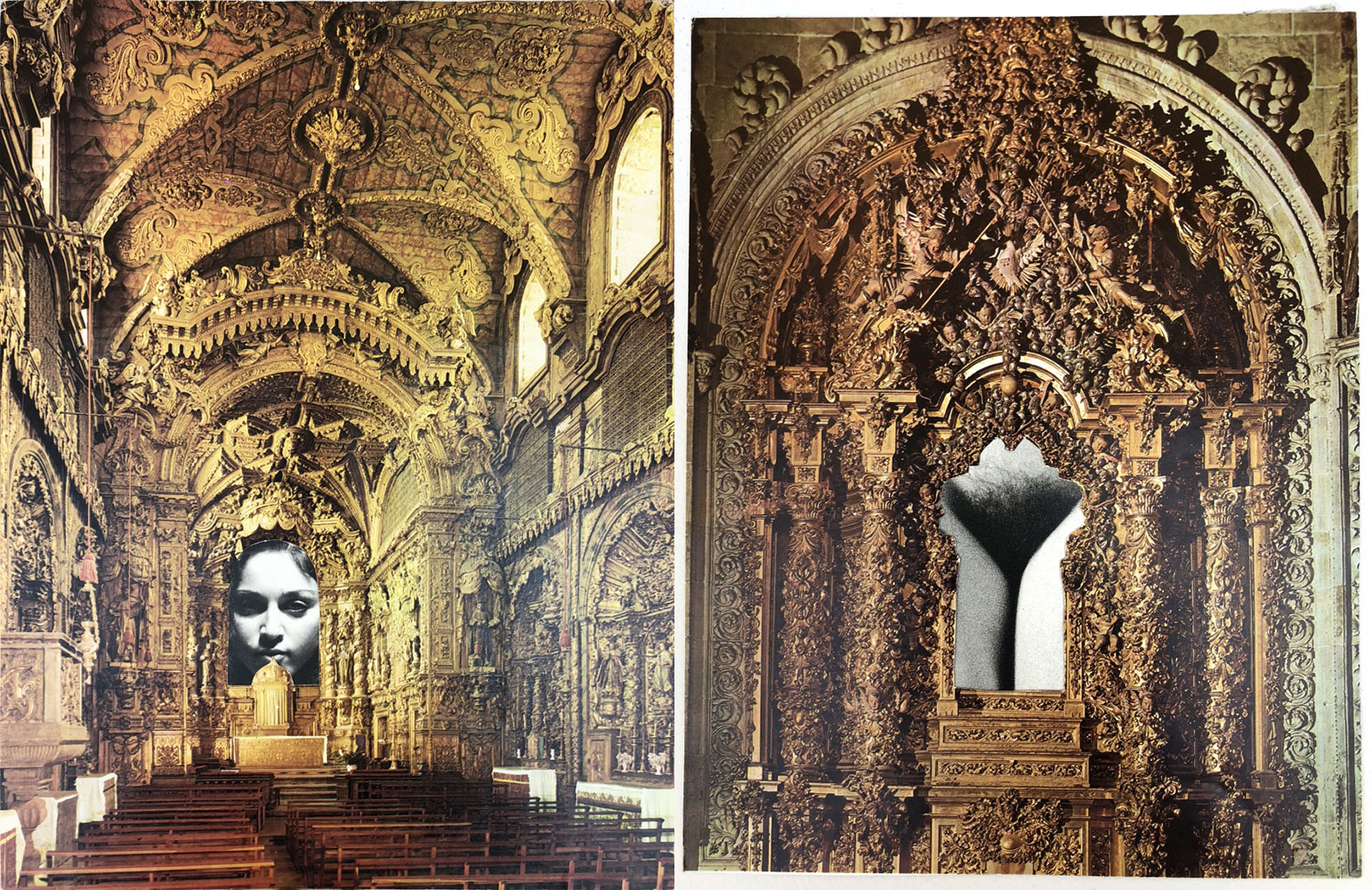

Ferrari reads the uses of the image in Western culture—from iconic figures of painting like Giotto, Fra Angelico or Michelangelo, to contemporary photojournalism—as an aesthetic enchantment that leads people to forget its ethical narrative. He therefore creates an “archive of cruelty” in which he shows how the image has served power as a means of justifying the most vicious forms of torture and extermination, from the Catholic Inquisition and the Crusades to the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, and the Argentine dictatorship. Through his visual and object montages and his literary collages, Ferrari experiments with forms to readjust the gaze, stir up emotions, and, at the same time, challenge the viewer to adopt a position. Moreover, his aesthetic-political investigations explore the communicative fault lines in language, blindness, error, illegible writings, or humor as ways to tense the literality of the word and the image, exploring other forms of beauty in order to extend the limits of the possible and the expressible. Rereading as a methodology runs through León Ferrari’s oeuvre. It is another name for his technique of collage and reassembly of meanings. Reading and rereading is also an archaeological exercise, a way of activating knowledge that does not emerge at first glance. Ferrari identifies the seed of war in the discourse of intolerance and punishment directed by the Judeo-Christian tradition at those who do not profess its faith. He rereads the Vietnam War from the standpoint of the religious justification for extermination of the other. From that archaeology of violence came “La civilización occidental y Cristiana” (Western Christian Civilization, 1965), in which a crucified Christ appears on an American warplane, a work he installed at the Instituto Di Tella in Buenos Aires. The institutional decision to withdraw the piece from the exhibition marked the beginning of a history of censorship that would follow his career. Ferrari sought to question a society whose apathy led it to naturalize these forms of violence. In the series “Relecturas de la Biblia” (Rereadings of the Bible), a set of collages produced beginning in 1985, Ferrari introduces images of war, but also of sex, science, and pagan culture, to rewrite the iconography of the religious texts of the Old and New Testaments. Several pieces in this series, which contain photographs of nuclear bombs superimposed on angels of the Apocalypse, resound and are reformulated in the material explosion of the polyurethane “Hongo nuclear” (Nuclear Mushroom, 2007), an image of the atomic bomb as the materialization of hell on Earth. In some of his visual and object collages, Ferrari denounces the Catholic Church’s discourse on hell as a form of illustration and exaltation of torture and the punishment of those who are different. Here he uses household utensils, trinkets, and religious articles to show saints and clerics exposed to the tortures of hell. Ferrari thought that the infernos depicted throughout history aroused no reaction or condemnation, and he therefore made his own version in which humans were replaced by the figures of those who had supposedly created or disseminated hell: saints, virgins, and Christs. Thus among these objects are plaster saints inside a blender, or a virgin covered with plastic cockroaches and scorpions, making up an ironic series on divine justice. Ferrari sought to reveal the absurdity of a faith that wins over the faithful with threats. He suggested that the true hell was mental: living with the idea of eternal punishment as a form of introjecting fear. Ferrari’s inferno objects provoked persistent reaction from different religious groups, whose protests culminated in the closure of the artist’s retrospective at the Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires. The protests were spurred on by and exaltation of torture and the punishment of those who are different. Here he uses household utensils, trinkets, and religious articles to show saints and clerics exposed to the tortures of hell. Ferrari thought that the infernos depicted throughout history aroused no reaction or condemnation, and he therefore made his own version in which humans were replaced by the figures of those who had supposedly created or disseminated hell: saints, virgins, and Christs. Thus among these objects are plaster saints inside a blender, or a virgin covered with plastic cockroaches and scorpions, making up an ironic series on divine justice. Ferrari sought to reveal the absurdity of a faith that wins over the faithful with threats. He suggested that the true hell was mental: living with the idea of eternal punishment as a form of introjecting fear. Ferrari’s inferno objects provoked persistent reaction from different religious groups, whose protests culminated in the closure of the artist’s retrospective at the Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires. The protests were spurred on by Jorge Bergoglio, today Pope Francis, who played a role in the judicial censorship of the exhibition., today Pope Francis, who played a role in the judicial censorship of the exhibition.

From the second half of the 1960s, the climate of political and cultural revolution led him to explore what he called an “art of meanings,” and to involve himself with a series of collective initiatives of artistic politicization that reached their high point with the experiment of “Tucumán arde” (1968). After this, he broke off his artistic work for ten years until the civil and military coup d’état of 1976 in Argentina. The dictatorship introduced a time of disappearance and death that brought with it a breakdown in frameworks of meaning. At this time, Ferrari started to draw again, as though he needed to find a new language to link him to the inexpressible. He also returned to collage in his series “Nosotros no sabíamos” (We Didn’t Know, 1976), news clippings from diverse Argentine newspapers explaining the disappearance of people, everyday traces of horror exhibited for all to see. Almost immediately, he went into exile in São Paulo with his family until 1991. Ferrari worked on a time scale that was simultaneously synchronic and diachronic. He moved between the intensity of historical detail and the perspective offered by an extensive time frame. On his return from exile, he reinforced his commitment against the impunity of the crimes of state terrorism. In 1992 he produced “La justicia” (Justice), a work that connects such distant and dissimilar historical processes as the conquest of America and the dictatorship in order to show us the continuity of an illegitimate and cyclically reproduced violence. La justicia evokes an altarpiece decorated with hundreds of encrypted messages in objects that point to the role of religion in the violent appropriation of America. After it was first exhibited in Germany in 1992, the work went missing for more than ten years. Retrieved in 2004, it was exhibited once more, under the title “1492–1992. Quinto centenario de la Conquista”, in the r/etrospective held on the artist at the Centro Cultural Recoleta, where it was vandalized by a group of orthodox Catholics.

Photo: León Ferrari, La civilización occidental y cristiana (Western Christian Civilization) [detail], 1965. Assemblage, © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou

Info: Curator: Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov, Assistant Curator: Diane Toubert, Guest Curator: Andrea Wain, Centre Pompidou, Place Georges-Pompidou, Paris, France, Duration: 20/4-29/8/2022, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 11:00-22:00, www.centrepompidou.fr

Right: León Ferrari. Apocalípsis, from the Relecturas de la Biblia series, 1986. Collage, 9 15/32 x 7 7/32 in. (24.1 x 18.4 cm.), © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou

Right: León Ferrari. Sin Título, 1986. Collage, 9 1/16 x 9 1/16 in. (23 x 23 cm.), © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou

Right: León Ferrari. Retablo, 1994. Collage, 8 21/32 x 6 11/16 in. (22 x 17 cm.), © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou

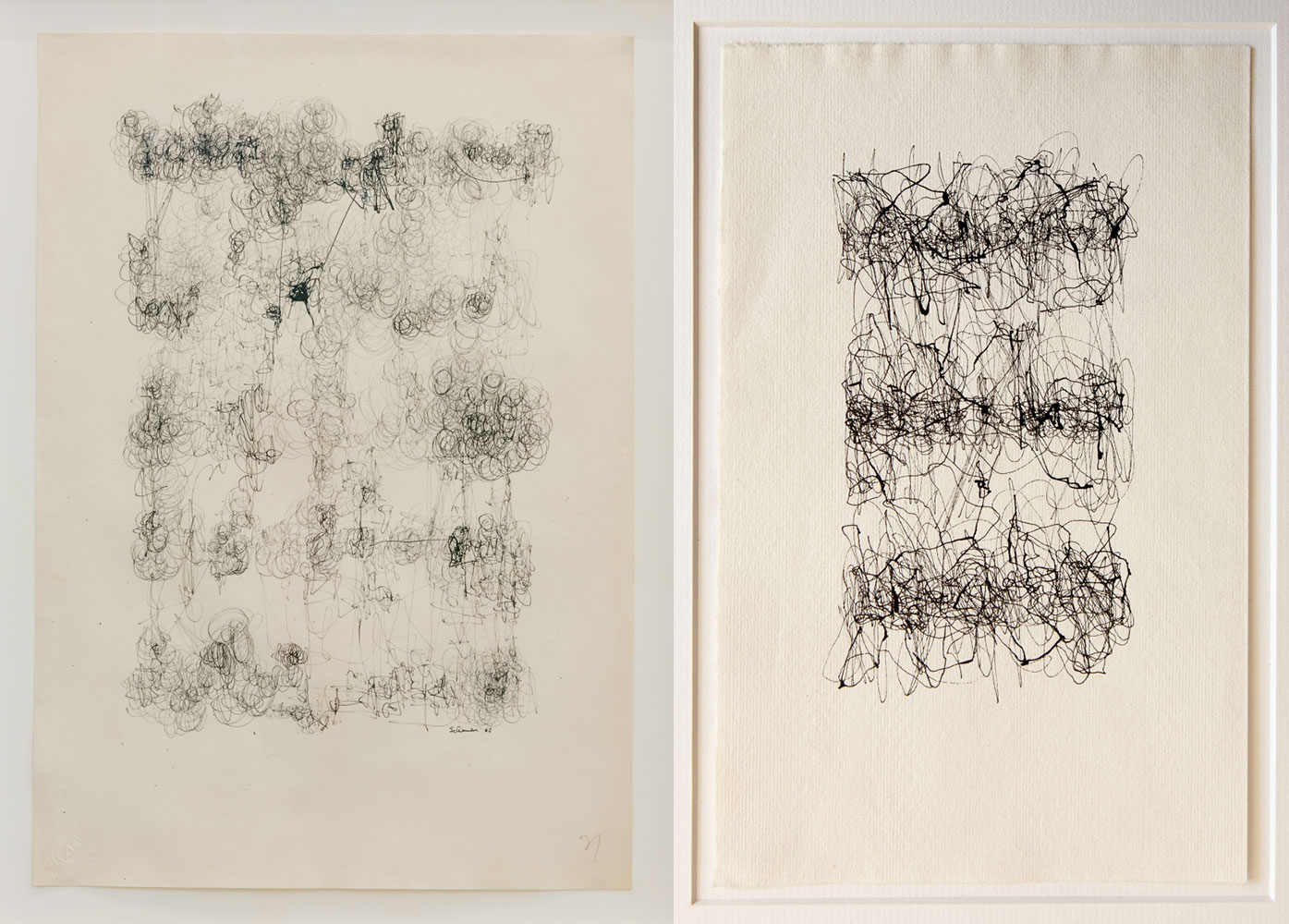

Right: León Ferrari. Sin Título, 1962. Ink on paper, 9 15/32 x 6 1/16 in. (24.1 x 15.4 cm.), © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou

Right: León Ferrari. Sin Título, 2009, Drawing, Ink and graphite on canvas, 39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in. (100 x 70 cm.), © León Ferrari Estate, Courtesy León Ferrari Estate & Centre Pompidou