PRESENTATION: Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture

Since the invention of the automobile, both its appearance and its association with speed, a sense of adventure, autonomy, modernity and progress seduced artists and architects to the point of quickly becoming a constant in their creations. The exhibition “Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture” covers over a century’s worth of automotive creation, exploring its multiple connections with the visual arts and architecture

Since the invention of the automobile, both its appearance and its association with speed, a sense of adventure, autonomy, modernity and progress seduced artists and architects to the point of quickly becoming a constant in their creations. The exhibition “Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture” covers over a century’s worth of automotive creation, exploring its multiple connections with the visual arts and architecture

By DimitrisLempesis

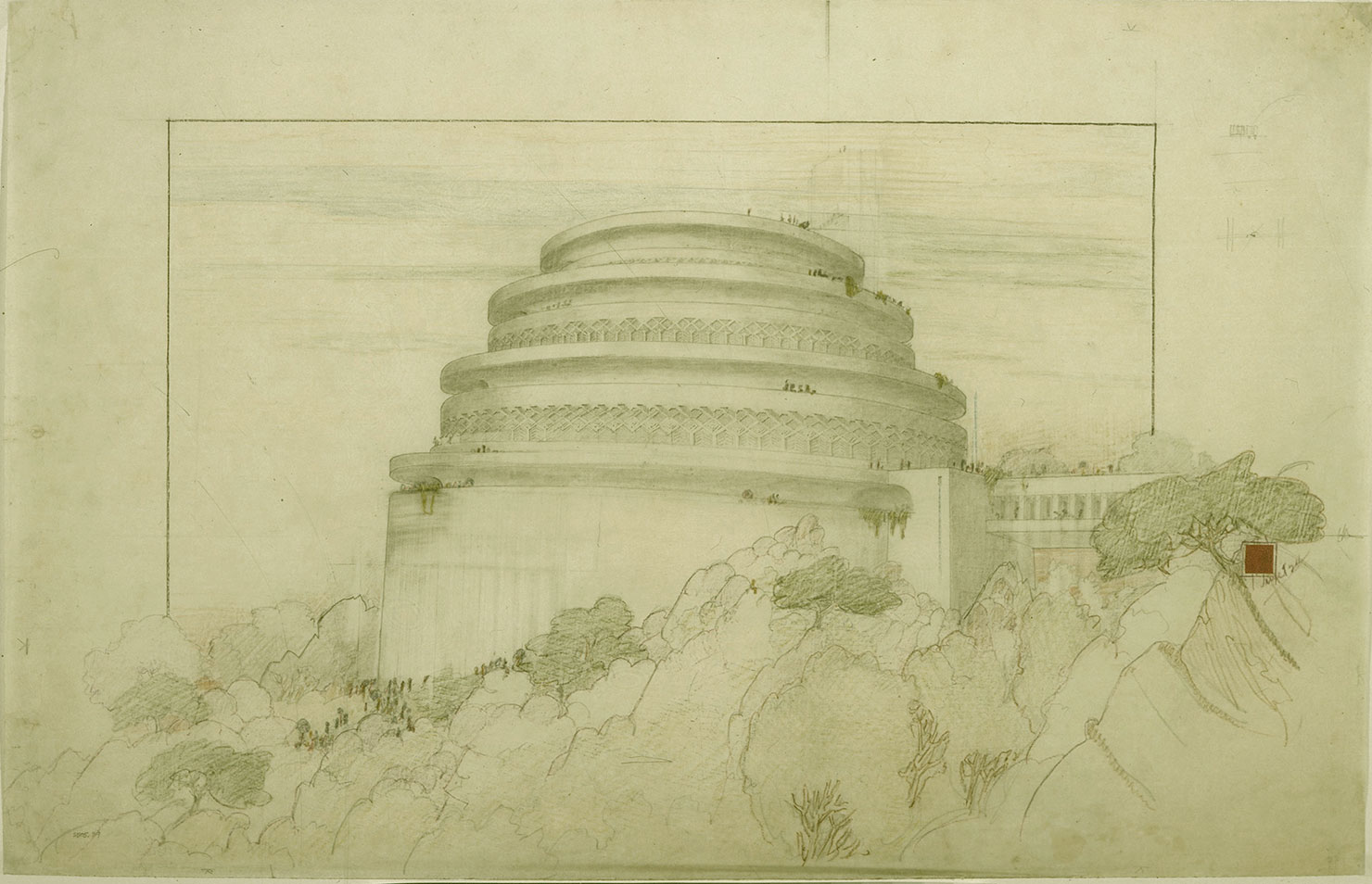

Photo: Guggenheim Museum Archive

Ideas and forms originating in the artistic avant‐garde impregnated automobile design, giving rise to the important collaborations of figures from art and architecture that we all know. The selection of vehicles, artworks of art and architectural documents that it comprises the exhibition “Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture” covers the main technological achievements in the sector and melds them with their enormous social and cultural implications. The exhibition brings together around forty automobiles – each the best of its kind in such terms as beauty, rarity, technical progress and a vision of the future. These are placed centre stage in the galleries and surrounded by significant works of art and architecture. Many of these have never before left their homes in private collections and public institutions, and as such, are being presented to a wider audience for the first time. The exhibition is spread over ten spaces in the museum. Each of seven galleries is themed in a roughly chronological order. These start with Beginnings and continue as Sculptures , Popularising, Sporting, Visionaries and Americana and close with a gallery dedicated to what the future of mobility may hold. Future shows the work of a younger generation of students from sixteen schools of design and architecture on four continents, who were invited by the Norman Foster Foundation to imagine what mobility might be at the end of the century, coinciding roughly with the 200th anniversary of the birth of the automobile. The remaining four spaces comprise a corridor containing a timeline and immersive sound experience, a live clay-modelling studio and an area devoted to models.

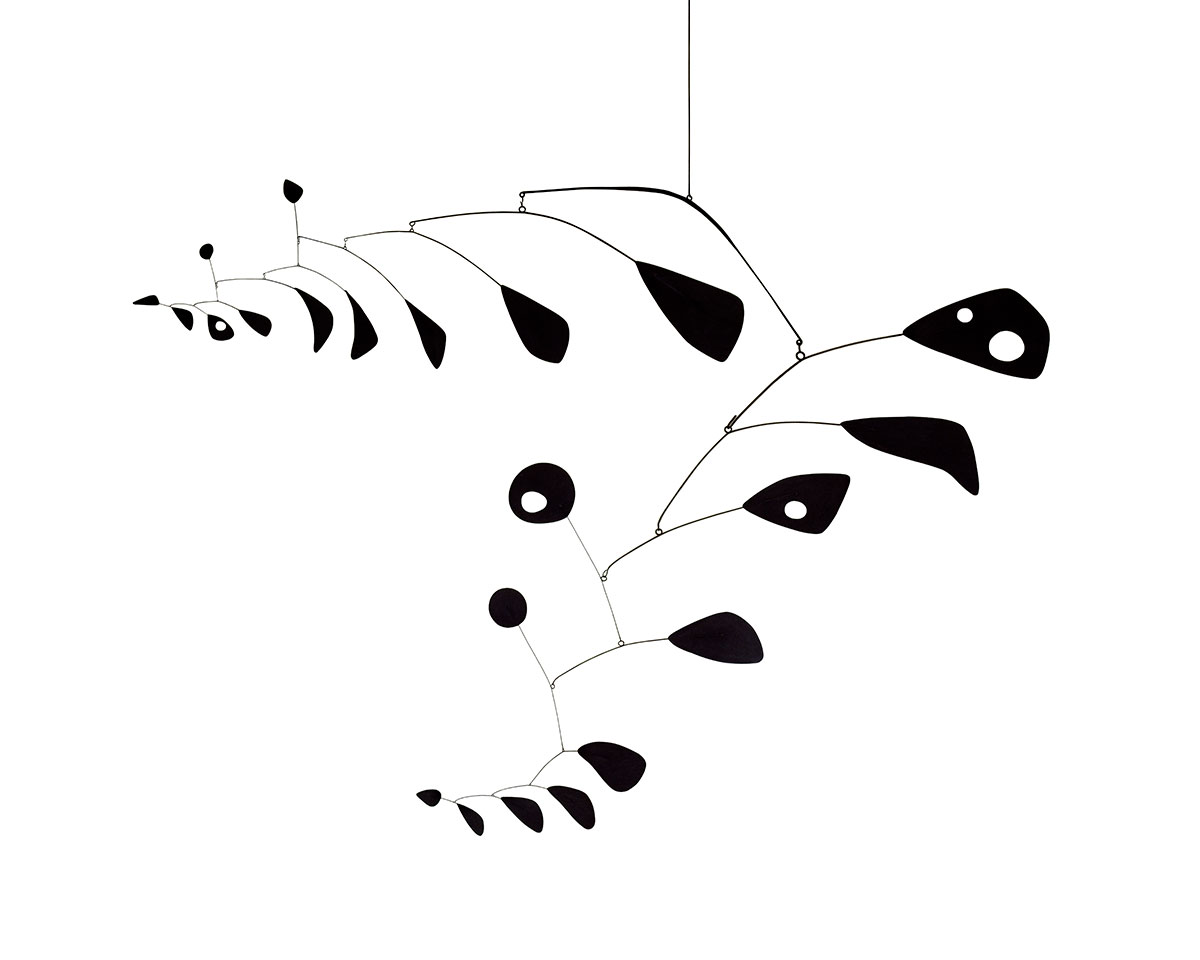

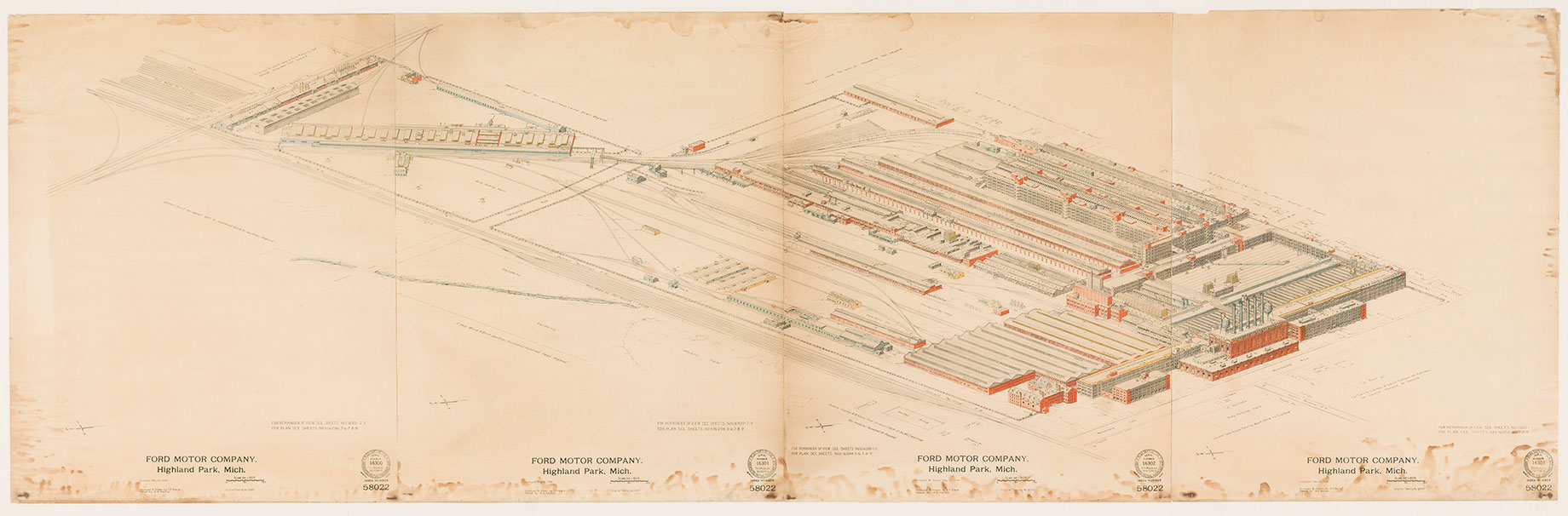

Beginnings: This gallery traces the birth of the automobile from the customised horseless carriage through to its mass-production – a process viewed within the concept of motion in the late 19th century using new technologies of photography and film. The automobile evolved from box-like angularity to sleek aerodynamic shapes, influenced by utilisation of the wind tunnel. This streamlined form was anticipated by the work of artists and architects in the first decades of the 20th century, and in the automobile, it became the very symbol of modernity. In the beginning, the automobile rescued cities from the stench, disease and pollution caused by horse-drawn vehicles. In an era of climate change the automobile has now become the polluting urban villain. However, battery power was also a dominant force from the earliest days of motoring. Included in the show is an example of the Porsche Phaeton of 1900 with electric motors embedded in the wheel hubs – a concept considered revolutionary when it drove NASA’s first buggy on the moon. Sculptures: The description of automobiles as “hollow rolling sculptures” was made by the Arthur Drexler in the early 1950’s. That proposition is affirmed by juxtaposing four of the most beautiful automobiles of the twentieth century with sculptures by two of the greatest artists of the same period – the soft curves of Henry Moore’s “Reclining Figure” and the restlessly fluid motions of Alexander Calder’s monumental “mobile 31st January”. Like great works of art, the Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic, Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia and Pegaso Z-102 Cúpula hold rare value as limited editions for connoisseurs. Even the mass-produced Bentley R-Type Continental numbered only around 200 examples. Popularising: This gallery shows how attempts to produce a reliable and affordable modern “people’s car” marked the next step in the evolution of the automobile. The process started in the 1930s with the deployment of national scale industries, often with political overtones. After the WWII, during a period of economic recovery and shortages, the automobile became a symbol of national pride and regeneration. Post war austerity-imposed limitations of size, cost and availability of materials but did not inhibit the creativity of designers – on the contrary they were spurs to encourage innovation and ingenuity – to do more with less. The art and fashion of the period fused with the mass appeal of mobility. For example, the Austin Mini and the mini skirt – Op Art and the logo by Victor Vasarely for Renault. Displayed automobiles like the Beetle and the VW Microbus are examples of how companies like Volkswagen have contributed to the democratization of the automobile.

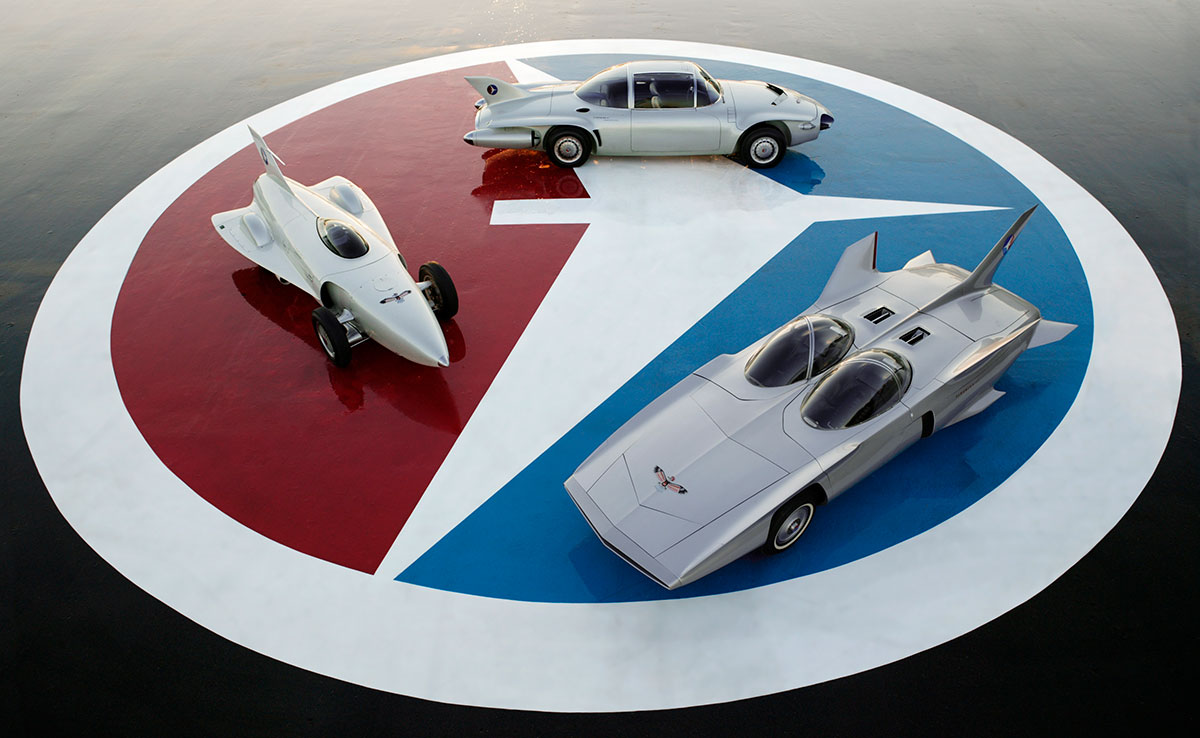

Sporting: In the post war economic boom years of the1950s and 60s the technical demands of competitive racing – particularly Formula 1 – saw racing and road automotive design diverge further into separate design disciplines. The market for fast sports cars expanded and drew on the technology of their racing counterparts. The five examples selected are each in their own way a delight to behold, quite aside from their racing pedigrees on roads and closed circuits. They merge art and fashion to satisfy the fantasy of speed and adventure – glamorous and desirable as objects of contemporary culture. The most emblematic examples became powerful images on the big screen, emulating the Hollywood stars in their degree of celebrity. These automobiles were portrayed as cult objects by artists and designers such as Andy Warhol and Ken Adams. In his lifetime, Frank Lloyd Wright owned more than eighty cars – many of which are classics and are featured in this exhibition. His unbuilt project in 1925, for Gordon Strong, the “Automobile Objective” shown here, was the first use of a central spiralling ramp which would later be the central feature of his Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Visionaries: Visionaries starts in the mid-20th century when the stage was set for utopian vehicles, and artists and designers explored radical new forms on the themes of speed and motion. Many anticipated possibilities for the future of driving that were decades ahead of their time. Automobiles inspired by the desire to go ever faster pushed the limits of engine technology and aerodynamic forms, inspired by the new technologies of turbine, jet, nuclear, and automation. This space celebrates a diverse range of visionary vehicles and their designers and contemplates the beauty of their fluid forms and aerodynamic achievements. These are exhibited alongside works from the Futurist Movement and its obsession with motion and speed, notably Umberto Boccioni’s “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space” (1913), with its bronze robes flowing as if in a wind tunnel. The utopian vison of automobile design is mirrored in the art and architecture of Eero Saarinen’s modernist masterpiece the General Motors Technical Center – described as an “industrial Versailles”. Americana: Nowhere has felt the impact of the automobile as fully as the United States. It has shaped the American economy, landscape, urban and suburban spaces as well as popular culture to a degree unseen anywhere else. It was the first country to feel the benefits of mass ownership – and the first to have to confront the environmental consequences of an auto-based society, with its energy consuming commutes and social isolation. The romance of the road, the transcontinental trip across the “big country” and its endless horizon, is emblematic of American culture with its enroute diners and filling stations. The storied road trip has been the subject of photographs, paintings, music, and literary tracts from the 1930’s new deal era through the present. Here, we can view through the camera lens of Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott, O. Winston Link, as well as the paintings of Ed Ruscha and Robert Indiana. As a backdrop to the automobiles, we can experience the precision of a sculpture by Donald Judd and compare it with the crushed relics of the automobile in a work by John Chamberlain.

Future: The exhibition’s finale is devoted to works by a young generation of students who were invited to imagine what mobility may be like at the end of this century, which coincidentally marks the 200th Anniversary of the birth of the automobile. The exhibition’s journey comes full circle by considering the same problems that auto inventors faced more than a hundred years ago – urban congestion, resource scarcity, and pollution – all exaggerated by climate change and now projected onto the future. Clay Modelling Studio: This mock-up of a section of an active studio shows the production of full-size clay models as part of the automotive design process and was pioneered during the 1930’s by Harley Earl, the Chief of Design of General Motors. This important process cannot be replicated and persists today across the industry despite advances in computer technology and virtual reality. General Motors’ Cadillac brand has enabled a working replica of the clay modelling studio featuring LYRIQ EV to be a live element of the exhibition. There are parallels with the studios of artists – today and in the past. Model cars: This area shows that the cultural significance of the automobile extends beyond the vehicles themselves to encompass the world of models and toys. With the help of the Hans-Peter Porsche Traumwerk collection a selection of clockwork toys provides fascinating artefacts from an era that celebrated mechanical objects. These are complimented by scale replica model automobiles that exhibit the same artistry found in miniature paintings, figurines, or jewellery.

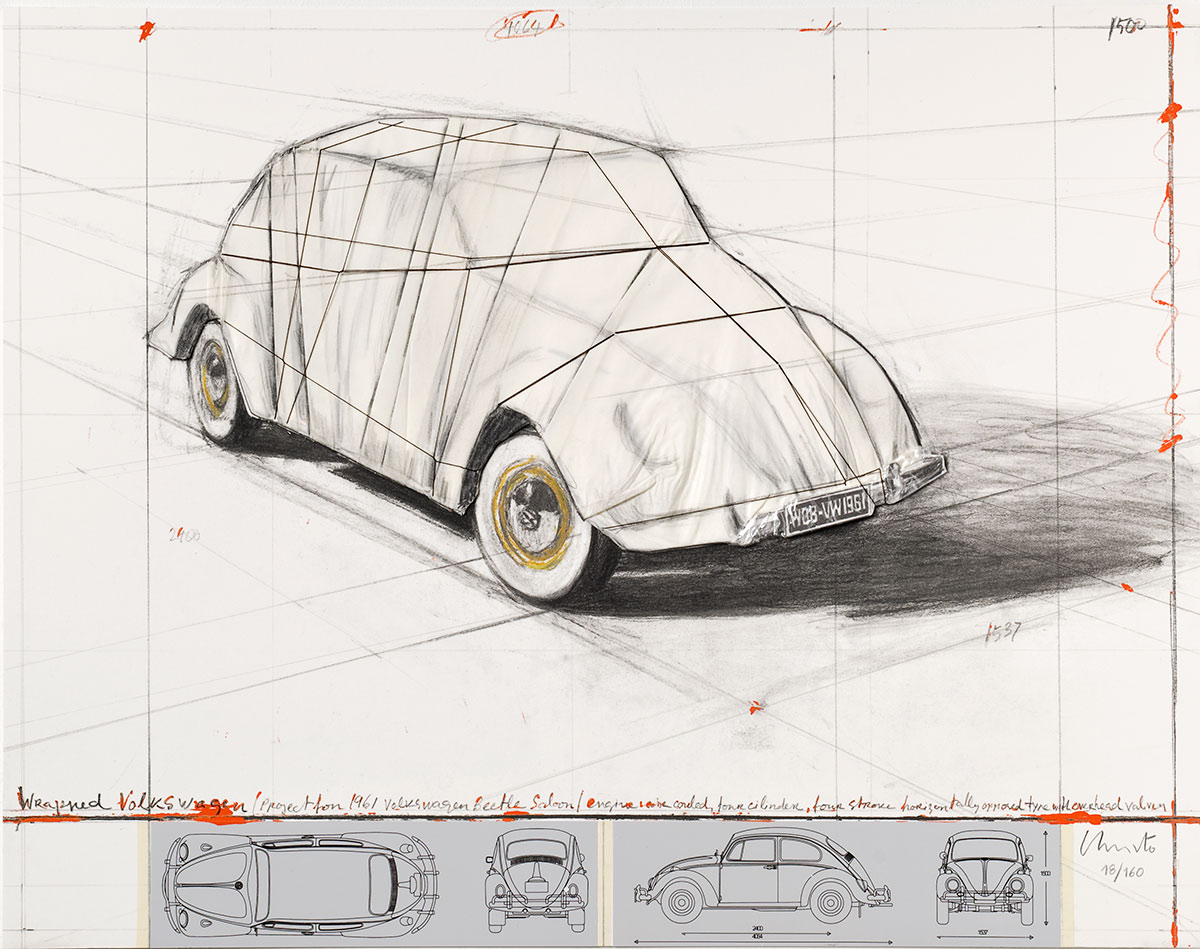

Photo: Christo, Wrapped Volkswagen (Project for 1961 Volkswagen Beetle Salon), 2013 (Project 1961), Collage graphic with original Volkswagen covered in fabric and hand- overpainting, 55.8 cm x 71 cm, Ed. Nr.: L/XC + 160 + 50 AP + 15 HC, Galerie Breckner, © Christo, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2022

Info: Curators: Norman Foster, Lekha Hileman Waitoller and Manuel Cirauqui, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Avenida Abandoibarra 2, Bilbao, Spain, Duration: 8/4-18/9/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-19:00, www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus

Constantin Brancusi, Fish (Le Poisson ), 1926, Polished bronze, 13.5 x 42 cm, Edition 3 of 8, Courtesy Kasmin Gallery, © Succession Brancusi – All rights reserved, VEGAP, 2022

Right: Andy Warhol, Benz Patent Motor Car (1886), 1986, Silkscreen, acrylic on canvas, 153 x 128 cm, Acquired 1986, Mercedes-Benz Art Collection, Stuttgart / Berlin , © 2022, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./VEGAP Photograph: Uwe Seyl, Stuttgar