ARCHITECTURE: Serious Fun-Architecture & Games, Part II

We are all familiar with the classic architecture games, from building blocks that become daring structures to board games where the players compete for spatial-strategic ad-vantages. What are, though, the architecture narratives invested in doll’s houses, along which guidelines do cities grow in computer games, and what kind of buildings shield ego-shooters from their assailants? The exhibition “Serious Fun – Architecture & Games “ shows and examines architecture games and toys (Part I).

We are all familiar with the classic architecture games, from building blocks that become daring structures to board games where the players compete for spatial-strategic ad-vantages. What are, though, the architecture narratives invested in doll’s houses, along which guidelines do cities grow in computer games, and what kind of buildings shield ego-shooters from their assailants? The exhibition “Serious Fun – Architecture & Games “ shows and examines architecture games and toys (Part I).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Architekturzentrum Wien Archive

The exhibition “Serious Fun – Architecture & Games“ presents games and reflections on games. The exhibits, many of which are interactive, were created by architects, artists and game developers. The visitor’s gaze is frequently drawn to specific, sometimes strange but frequently innovative aspects of architecture games. What are the utopias and dystopias that they evoke, what are the values and ideas they convey, criticise or endorse? What kind of places, themes and ways of life are frequently left out, and which games fill these gaps? Visitors can take an alternative city tour through a videogame environment, they can dabble on the virtual London property market, experience doll’s houses as lurid minidramas or emancipatory narratives, stimulate the spatial experience of a blind person in a purely acoustic videogame, or develop eco-friendly city districts in collaboration with others. The exhibition invites visitors to play and to ponder. It provides an opportunity to become immersed in both familiar and in less familiar games, while it also encourages people to take a step back and to take a critical look at the world of games and the constructed worlds that they create. Games can both celebrate and trivialise architecture, they can delimit and they can de-limit whole worlds. They do not only integrate architectural practice, they also hold a mirror up to it. In Maykel Roovers ,“Critical Blocks” (2012), a mega farm, a power plant or a highway as toy building blocks. For the designer Maykel Roovers, they embody essential elements of today’s architecture and spatial planning. Large-scale architecture is abstracted by the toy blocks and the contrast between the hardness of these urban buildings and the playful children’s world, which feigns friendliness and limitless possibilities, is emphasized. The “Listening House” by architect Machiel Spaan and composer Rozalie Hirs is a doll-house that children with and without disabilities can play together with. The house-shaped wooden sculpture has seven hollow spaces that you can explore with your ears. A dollhouse has a time and a life of its own. It appears as if detached from the environment. Weather, catastrophes and deterioration pass it by. Artist Alice Pasquini causes these foundations to sway in “The Unchanging Worl” (2018). History has left deep marks on her dollhouse with broken windows, glass shards and ruined furniture. Viewed from the outside, Yinka Shonibare’s “Utitled (Dollhouse)” (2002) is a miniature copy of the upper-class Victorian house in London’s East End where the artist himself lives. The humorless, smug architectural style contrasts with the shrill interior design, which boasts colorful wallpaper and upholstery made of Vlisco batik fabric. The material embodies the complexity of (post-)colonial relations against the background of globalization and the shaping of multicultural identities.

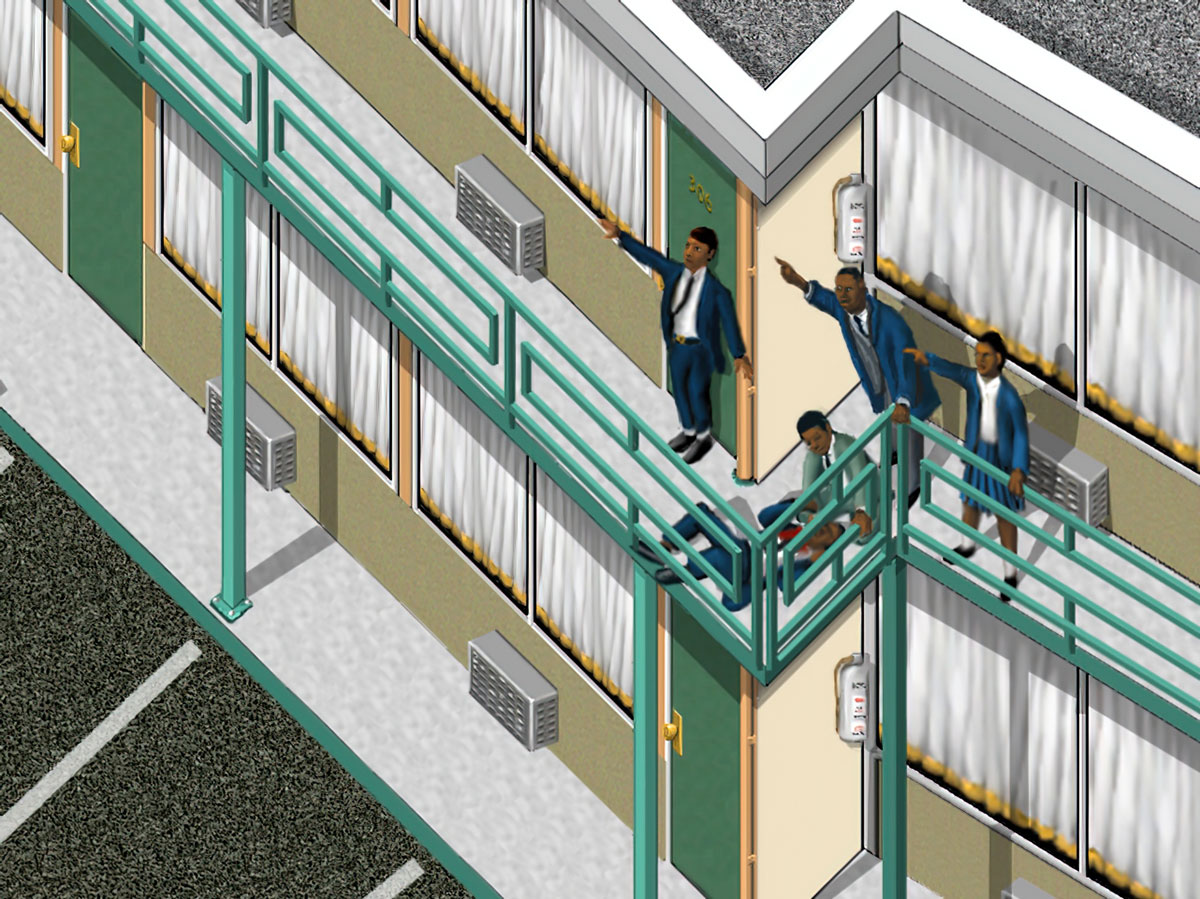

Heather Benning’s film “The dollhouse” (2014) is a modest farmhouse on the Canadian prairies that appears to have been hastily abandoned by its residents. It looks like an enlarged miniature: The artist transformed a real house into a dollhouse. After six years of decay, the artist let it go up in flames and filmmaker Chad Galloway turned this event into a film. Dollhouses from the GDR play the main role in the documentary Eigenheim” (2012) by Anja Dornieden & Juan David González Monroy: Slow close-ups move the viewer through the East German miniature world of the 1960s and 1970s. From a child’s per-spective, the houses convey the living ideals of the era. In addition to the moving images, frag-ments of interviews with old and new owners can be heard. “Dust” (2011) and “Dust Scapes: (2013) by Aram Bartholl are a 1:333 scale model of the spaces of one of the most played computer games in the world. Passionate gamers spend whole days and weeks in such environments; for Bartholl they have long been part of our cultural heritage: They appear more real than many other places such as artificially laid out supermarkets or airports. In “The Continuous City” (2018), British artist and game designer Gareth Damian Martin explores video game scenarios and captures projected scenes with a 35mm analog camera. The resulting images move be-tween reality and fiction, between the digital and analog world. They testify to the ability of video games to create worlds that have absorbed real architecture. In his “Isometric Screenshots” (2000), Jon Haddock imitates the isometric representations and the pixelated style of the first version of the world-famous computer game The Sims. Dramatic events of world importance, such as the assassination of Martin Luther King, are mixed with fictional scenes such as the picnic from The Sound of Music. Alan Butler’s “Down and Out in Los Santos” (2015) consists of screenshots from the well-known video game Grand Theft Auto V. The artist moves like a social reporter through the streets and uses his avatar’s virtual smartphone to record poverty and homelessness. He criticizes both the aesthetic representations of street photography and the society that is apparently portrayed here so realistically. The starting point for Hans Venhuizen’s “Parquette” (1991 & 2008) was the observation that no meaningful urban development can arise on a tabula rasa. Parquette therefore simulates a development process. In the course of the game, constantly growing framework conditions are created and the participants are asked, in consultation with one another, to position themselves. This enables the players to gain insight into the dynamics of urban development, the positions of the other participants, and the potential of the area.

Photo:Exhibition view “Serious Fun. Architecture & Games”, © Architekturzentrum Wien, photograph: Lisa Rastl

Info: Curator: Mélanie van der Hoorn, Architekturzentrum Wien, Museumsplatz 1, Vienna, Austria, Duration: 17/3-5/9/2022, Days & Hours: Daily 10:00-19:00, www.azw.at