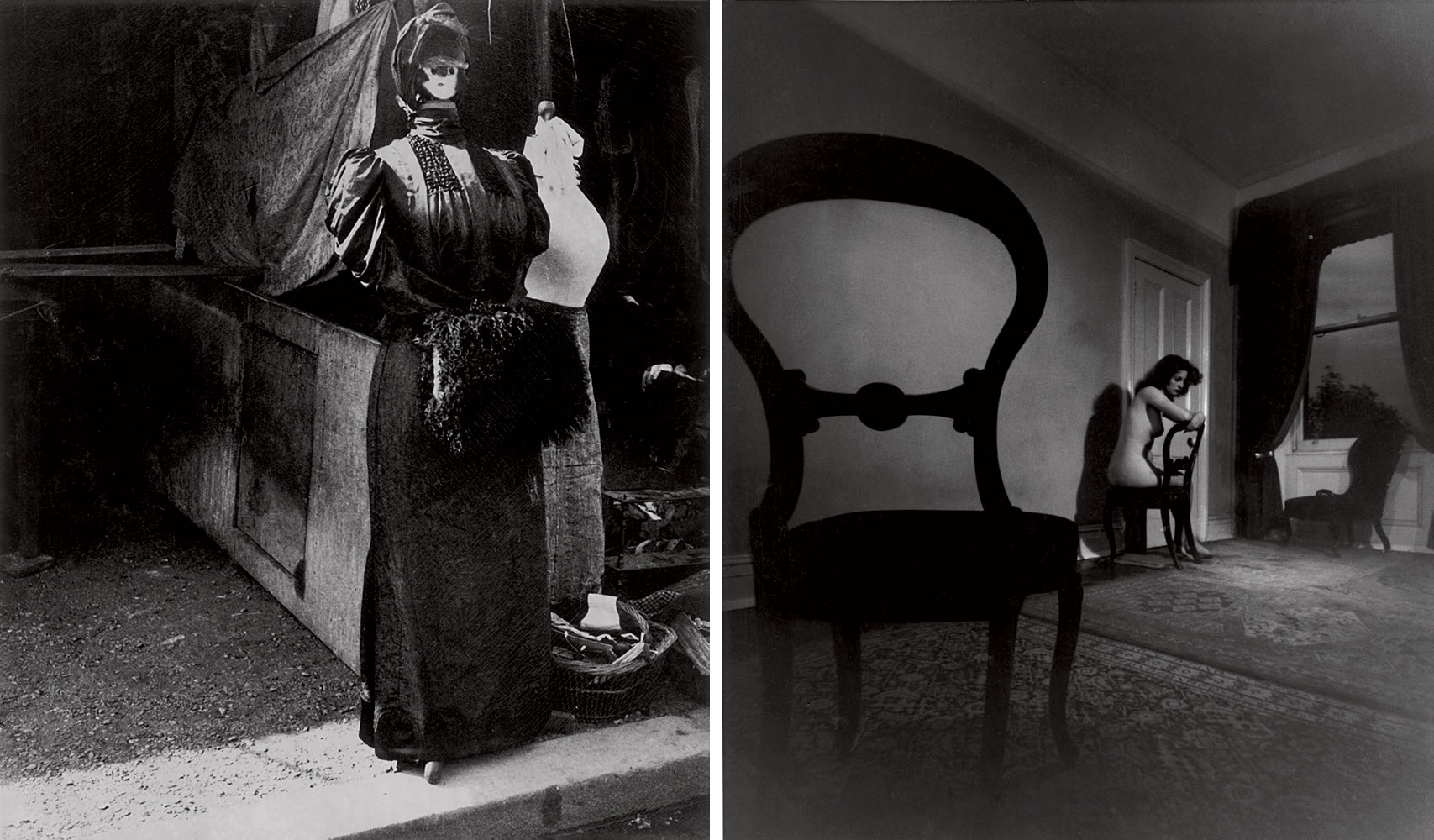

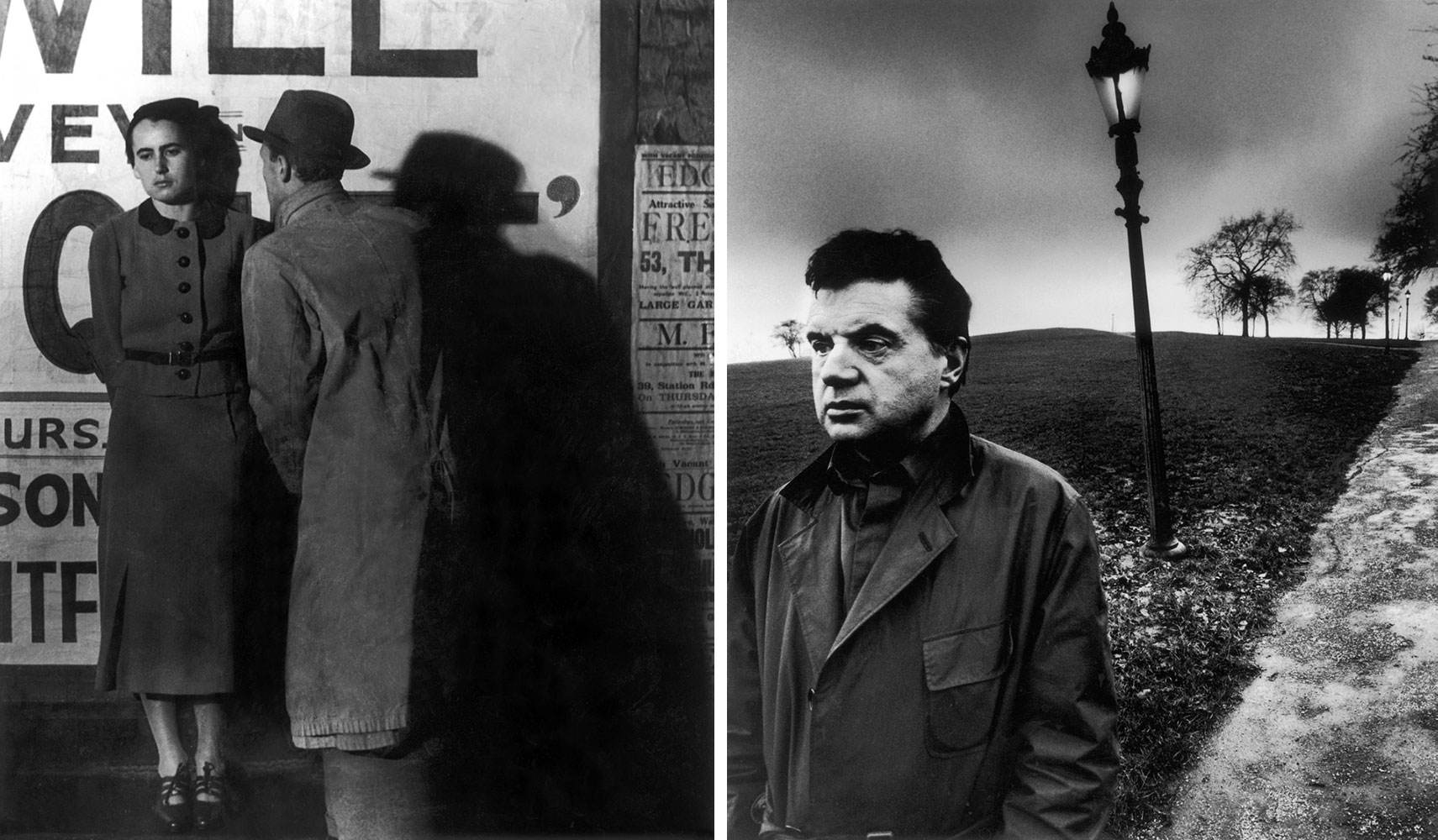

PHOTO: Bill Brandt-The Beautiful and the Sinister

Bill Brandt was one of the most influential British photographers of the 20th century. He photographed vivid interactions of social life and the realities of labour and class with imagination, compassion and humour. He was a witness to the Depression of the 1930s and the Blitz of 1940 and is credited with revising and renewing the major artistic genres of portraiture, landscape and the nude.

Bill Brandt was one of the most influential British photographers of the 20th century. He photographed vivid interactions of social life and the realities of labour and class with imagination, compassion and humour. He was a witness to the Depression of the 1930s and the Blitz of 1940 and is credited with revising and renewing the major artistic genres of portraiture, landscape and the nude.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Foam Archive

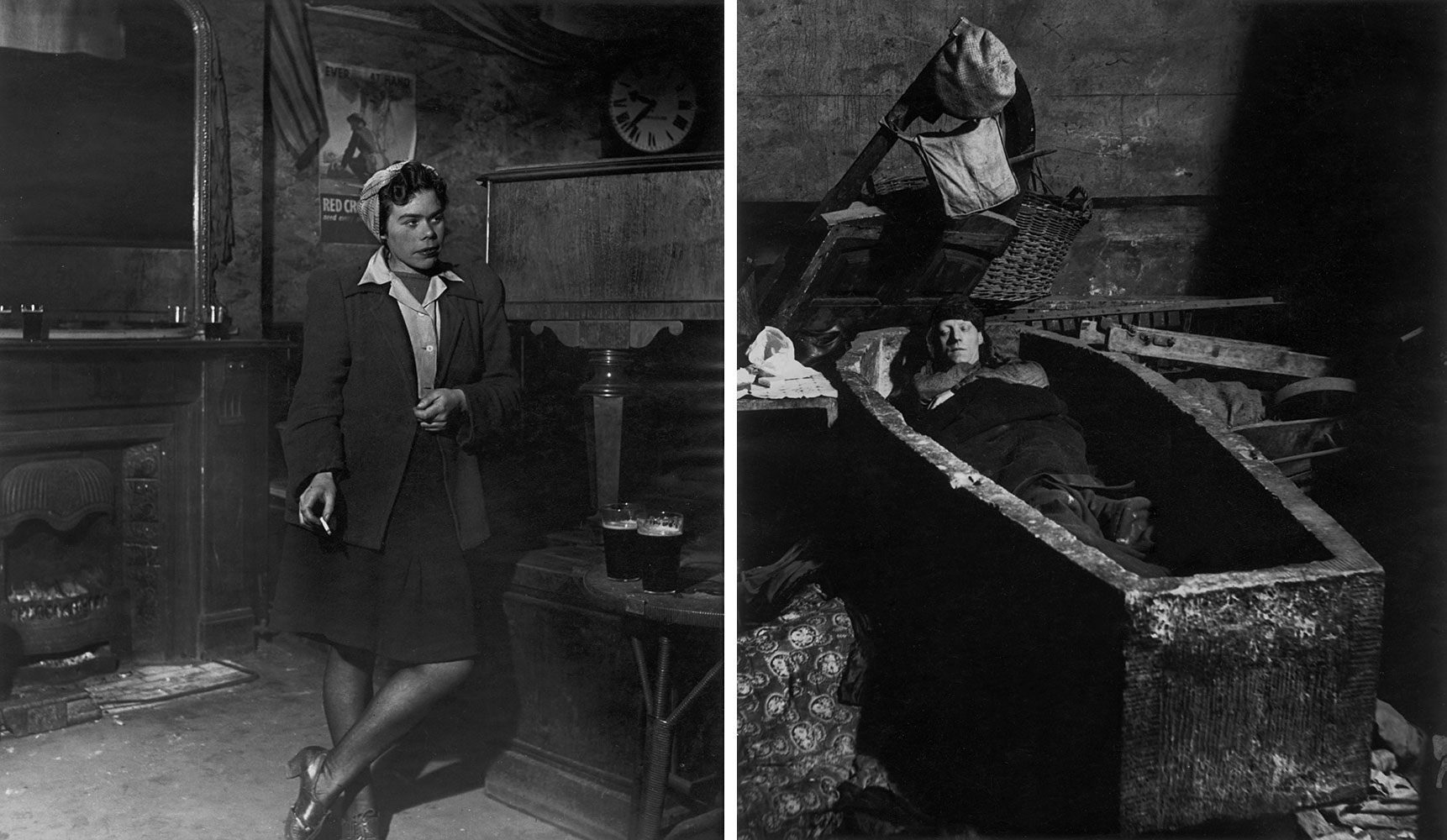

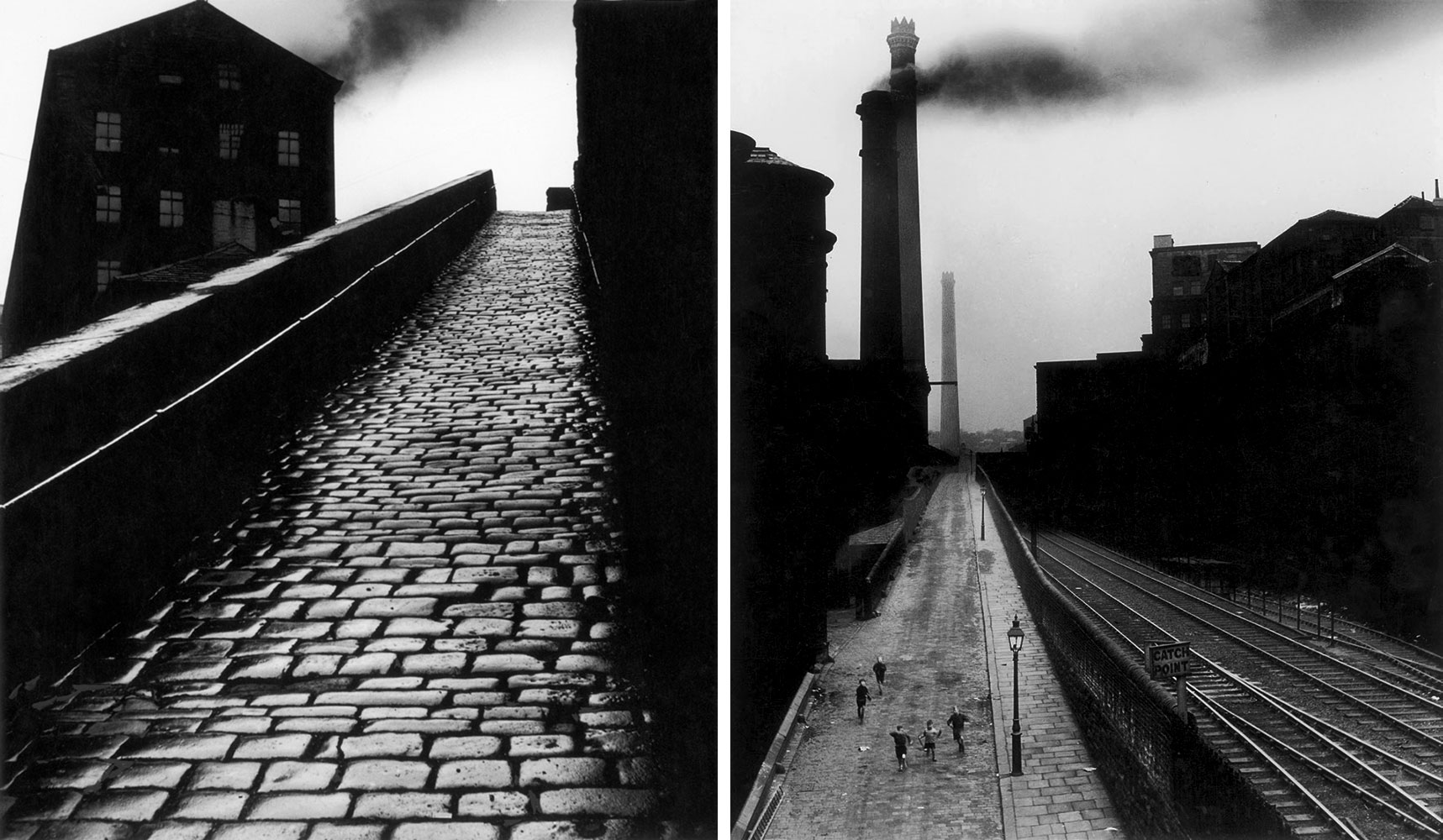

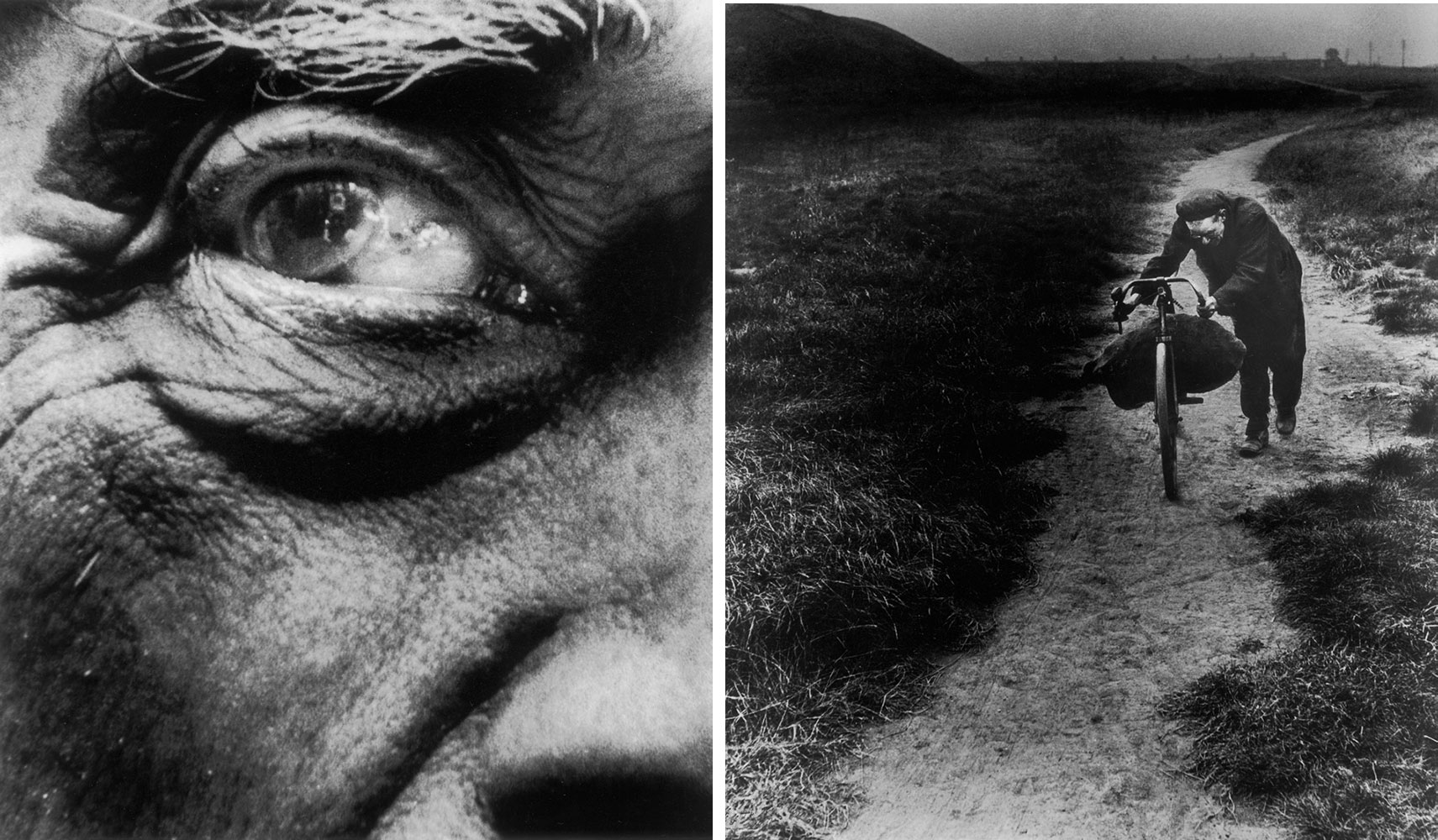

The exhibition “The Beautiful and the Sinister” demonstrates the close relationship existing between the work of Bill Brandt and the art of the European avant-garde, in particular Surrealism. Departing from the notion that the sinister (unheimlich) is an ever present element of Brandt’s photographs, the exhibition shows how this characteristic manifests itself in both his artistic and documentary practice. The exhibition also reveals the relationship between Brandt’s images and Dada and Surrealism. This interest is reflected in clear references to psychoanalytical issues, expressed through increasingly sombre tones and an obsession with collecting found objects. Considered one of the most influential British photographers of the 20th century and one of the artists who, together with Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson and others, laid the foundations of modern photography, Bill Brandt’s oeuvre can be considered an eclectic one, reflecting a career of nearly five decades during which he encompassed almost all the photographic genres: social documentary, portraiture, the nude and landscape. Born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt in Hamburg in 1904 to a wealthy family of Russian origin, after a period living in Vienna and Paris Brandt decided to settle in London in 1934. Within the context of growing hostility to all things German due to the rise of Nazism, he attempted to erase all traces of his origins to the point of stating that he was British by nationality. This concealment and the creation of a new personality enveloped Brandt’s life in an aura of mystery and conflict that was directly reflected in his work. His images aim to construct a vision of the country that he embraced as his own, although not of the real country but rather of the idea that he had created of it during his childhood through reading and from stories told by relatives. Brandt had tuberculosis as a child and it was seemingly in the Swiss sanatoriums at Agra and Davos where his family sent him to convalesce that he first became interested in photography. After some years in Switzerland he moved to Vienna to undergo an innovative treatment for tuberculosis based on psychoanalysis. Imbued with a post-Romantic air, Brandt’s photography always seems to be located on the edge, provoking simultaneous attraction and rejection. It can be related to the concept of unheimlich, a term first used by Sigmund Freud in 1919. The adjective unheimlich – generally translated as “the uncanny”, “the sinister” or “the disturbing”, and which according to Eugenio Trías “constitutes the condition and limit of the beautiful” – is one of the characteristic traits that remains present throughout Brandt’s career. Psychoanalytical theories were among the fundamental pillars of Surrealism and their influence extended to the entire Parisian cultural scene in the 1930s. Brandt and his first partner, Eva Boros, moved to the French capital in 1930 where he worked as an assistant in Man Ray’s studio. It was at this point that he assimilated the ideas circulating in a city filled with young artists, many of them immigrants looking to make their way in the professional art world. His images of this initial period suggest a catalogue of psychoanalytical “themes”, clearly reflecting the influence of Surrealism on him even though he never actively participated in any of the historic avant-garde groups. Almost all Brandt’s images, both the pre-war social documentary type and those from his subsequent more “artistic” phase, possess a powerful poetic charge as well as that very typical aura of strangeness and mystery in which, as in his own life, reality and fiction are always combined. During his years in Paris Brandt established connections with the Surrealist circle and with groups of photographers who aimed to make the camera both a means of expression and of earning a living. He never followed the principal trends and focused his attention on the daily life of the suburbs rather than on events of the day. Brandt’s photographs of this period reveal how he increasingly assimilated Surrealist concepts into his way of seeing.

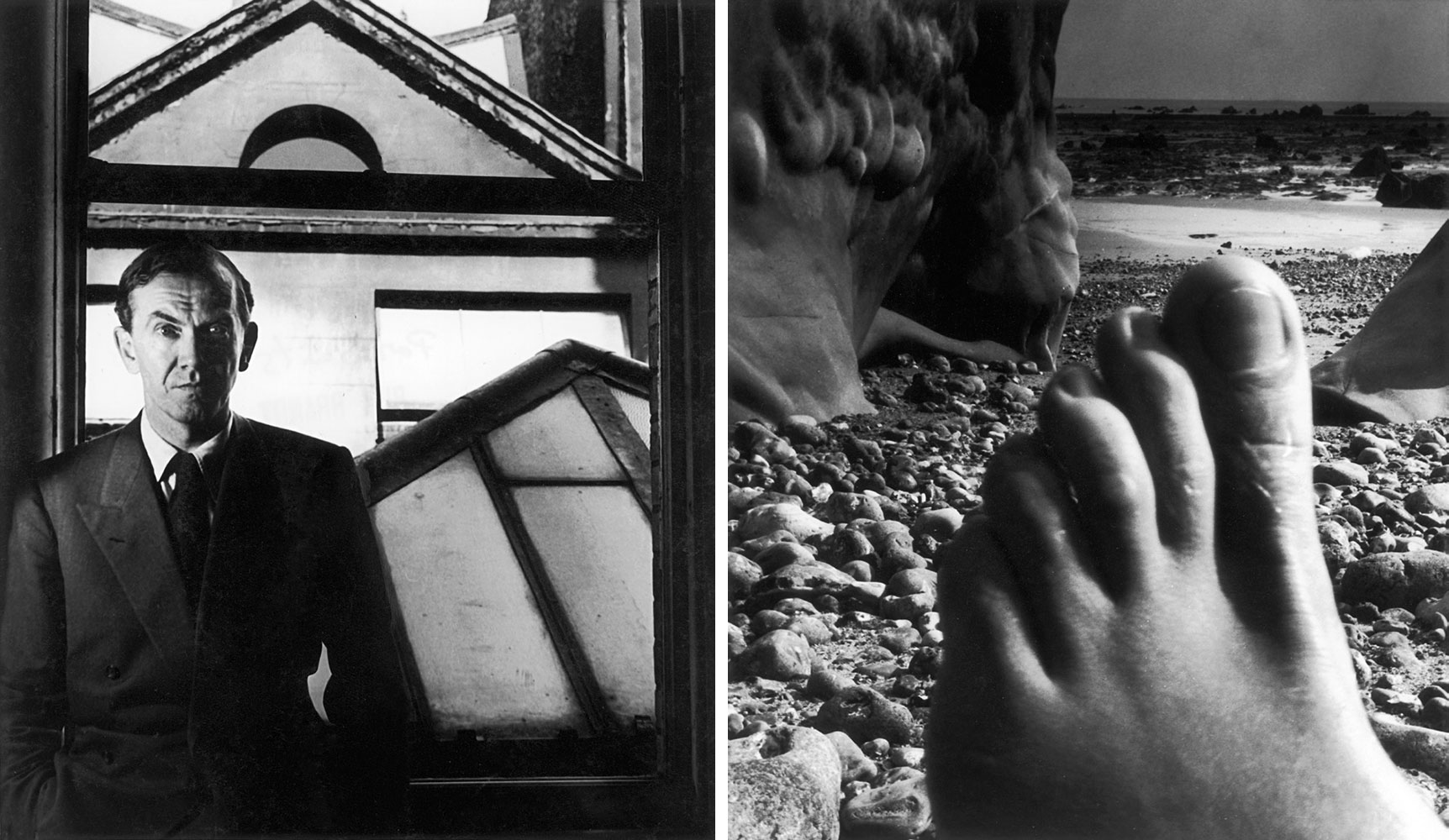

The growing antipathy on the part of the British towards Nazi Germany meant that many immigrants who had arrived from the latter country changed their name. Brandt went even further than this as he completely concealed his origins and for more than twenty-five years passed himself off as a British citizen. The 1930s was the decade of the great social protest movements and of strikes over working conditions following the 1929 financial crash. It was within this context that in 1936 Brandt published his first book, “The English at Home”, produced in a wide, album format. He employed a design particularly favoured by Central European graphic publications based on the combination of opposites in order to achieve a significant contrast between each pair of photographs. With these double-page spreads Brandt aimed to juxtapose two opposing social classes, thus generating two parallel narrative discourses without mixing them together. Following the outbreak of World War II Brandt started to work for the Ministry of Information. It was at this point that he produced two of his most famous series of images: his photographs of Londoners sleeping in Underground stations converted into improvised shelters; and his images of the city at ground level, showing a ghostly London lit only by the moon as protection against the air raids. Brandt abandoned the class differences that he had previously portrayed in favour of other types of scenes which denounced the effects of the war on the civilian population. As a portraitist, a genre to which he devoted himself professionally from 1943, Bill Brandt considered that the photographer’s aim should be that of capturing a “suspended” moment rather than just the appearance: “I think a good portrait ought to tell something about a subject’s past and suggest something about their future”; in other words, achieving an image that asks questions and raises issues about both the sitter and the viewer. Some of Brandt’s portraits mark a break from tradition, such as the ones published in the magazine Lilliput in 1941 to accompany the article “Young Poets of Democracy”, which includes images of some of the leading names of the Auden generation. Brandt subsequently began to distort the space in his portraits, for example “Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, London” (1963). He also produced a new series of portraits of eyes of clearly Surrealist inspiration. The eyes of Henry Moore, Georges Braque and Antoni Tàpies are among the examples of gazes that transformed the way of seeing and representing the world. In 1944 Brandt returned to the theme of the nude. For the artist, documentary photography had become a widely extended fashion while the old Great Britain with its marked class divisions was now something of the past. It should also be remembered that the nude is one of the traditional themes of painting and as such signals Brandt’s evolution from documentary photography to the social status of “artist”. In the 1950s he visited the French Channel Coast beaches in order to make a series of portraits of the painter Georges Braque. Seeing those pebble beaches led to a change of direction and he started to photograph stones and parts of the female body as if they were stones themselves. He combined flesh and rock, heat and cold, hardness and softness in a single formal discourse. The distortions are often so pronounced that the parts of the body have lost any reference point but they nonetheless produce sensations that are more poetic or profound. It may be that for Brandt these “fragments” of the human body in comparison or communion with natural forms represented primordial forms of some type through which we can perceive “the totality of the world”, as with the Urformen of the Gestalt School and its theory of perception. Brandt’s nudes of the late 1970s bear no relation to his earlier ones. They transmit a certain sense of violence which reveals the alienation of an artist who no longer felt himself part of the world in which he lived.

Photo: © Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Info: Curator: Ramón Esparza, Foam, Keizersgracht 609, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Duration: 18/2-11/5/2022, Days & Hours: Mon-Wed & Sat-Sun 10:00-21:00, www.foam.org