PREVIEW: Shirin Neshat-Land of Dreams

Shirin Neshat’s powerful photographs and video installations illuminate the gender and cultural conflicts of her native Iran. From her first series of photographs, “Woman of Allah” (1993–97), combines images of women with written words taken from religious texts. Neshat further explored cultural taboos through video and video installations. In 1997, she won the 48th Venice Biennial prize for her film “Turbulent”, which contrasts a man singing in front of an all-male audience, with a woman singing to an empty concert hall.

Shirin Neshat’s powerful photographs and video installations illuminate the gender and cultural conflicts of her native Iran. From her first series of photographs, “Woman of Allah” (1993–97), combines images of women with written words taken from religious texts. Neshat further explored cultural taboos through video and video installations. In 1997, she won the 48th Venice Biennial prize for her film “Turbulent”, which contrasts a man singing in front of an all-male audience, with a woman singing to an empty concert hall.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MOCA Archive

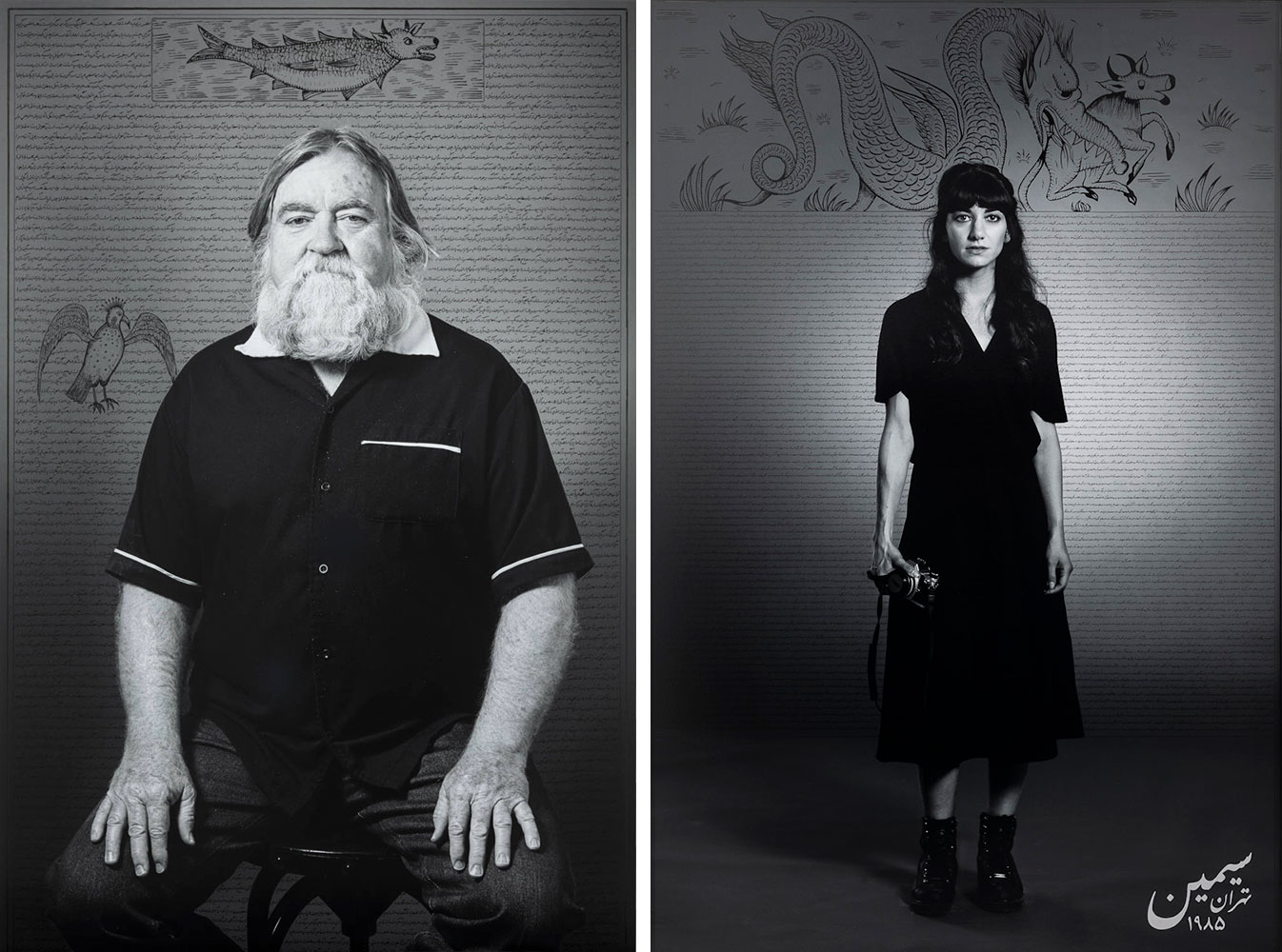

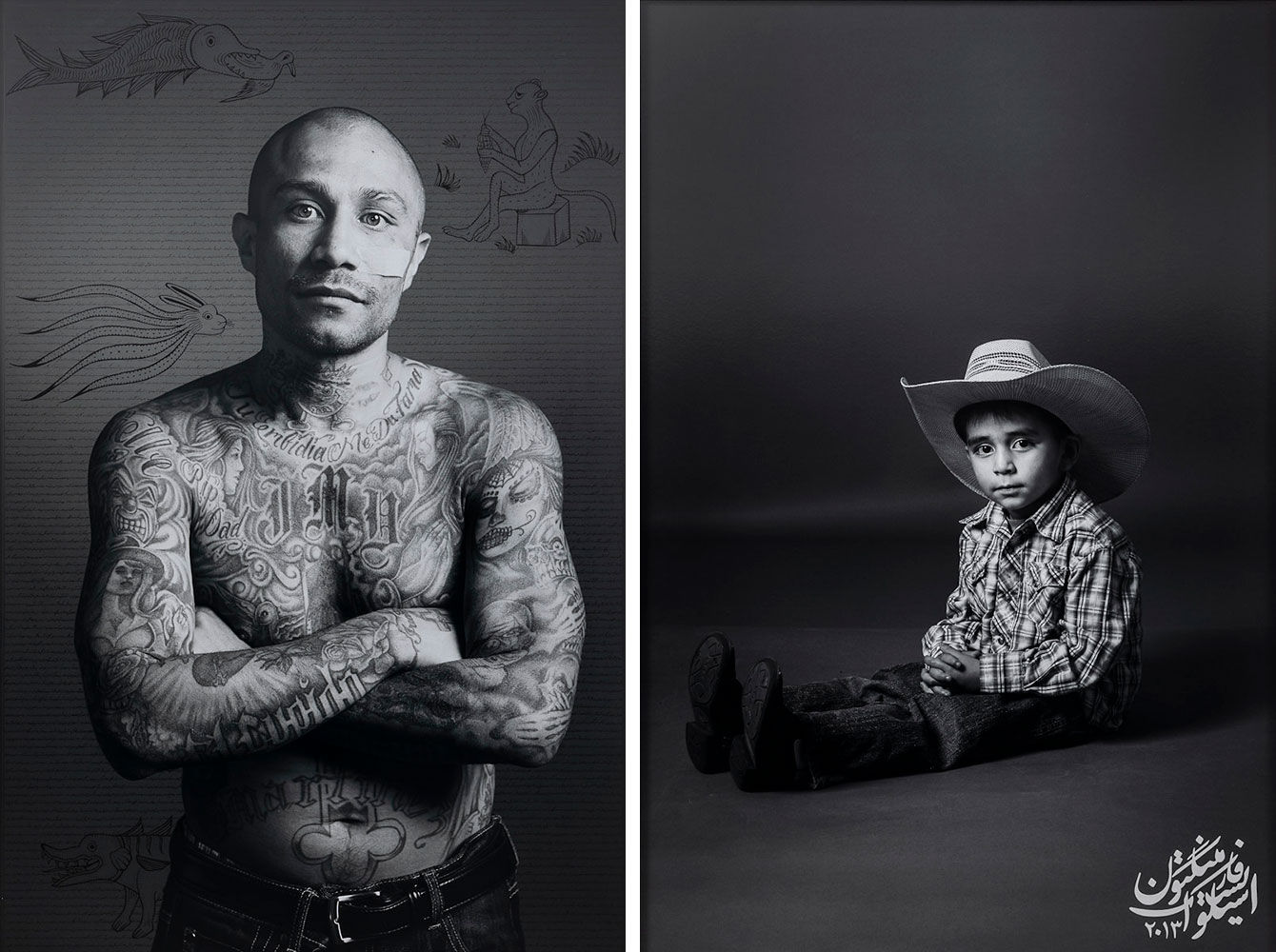

“Land of Dreams”, Shirin Neshat’s first major exhibition in Canada in 20 years, includes her recent work of the same title that sees the convergence of photography and film into one immersive experience that presents a portrait of contemporary America. Created in 2019 in New Mexico, “Land of Dreams” is a multidisciplinary project, both fictitious and documentary in nature, that captures the state’s diverse American population. The first film on the two-channel video installation follows a young Iranian art student named Simin, who travels around suburban and rural areas of New Mexico photographing local residents in their homes. As part of the protagonist’s assignment, Simin asks her subjects about their most recent dreams. As the people she encounters vividly detail their dreams, the viewer is transported into these imagined narratives alongside Simin, who wanders inside each participant’s subconscious mind. Neshat infuses the film with cinematic views of New Mexico’s sublime landscape alongside the everyday streets and neighborhoods where Simin travels. The second film reveals a sinister twist to the protagonist’s seemingly innocuous assignment: Simin is uncovered as an Iranian spy tasked with archiving the dreams and portraits she captures, which are recorded and analyzed in a bunker set within the mountains of New Mexico. Unlike the dozens of dream scientists who quietly work and diligently follow orders in the factory-like facility, Simin is noticeably perplexed by one of her subjects, leading her on a path to try and find their subliminal connection. Through her incisive ability to allude to the absurdities and similarities between the United States and Iran, Neshat astutely explores the complexities between the ephemeral nature of dreams and the dangerous impact of oppressive political ideologies and policies to reveal a shared humanity. Alongside the film, the photographic installation “Land of Dreams” comprises 111 photographs of New Mexico residents who Neshat captured throughout filming. Similarly to Simin, Neshat asked her subjects about their dreams, which she recorded in Farsi on many of the portraits, along with the sitters’ names and dates and places of birth. The artist’s practice of applying calligraphy to portraits recurs throughout her oeuvre, and in many of these new photographs, Neshat additionally included technically intricate, ornate drawings that depict fantastical elements of the dreams. The artist notes, “We drove across the country to search for a landscape that at once looked like Iran and America’s Southwest. We settled on New Mexico not only for its spectacular nature but also for its demographically diverse communities of Native Americans, African Americans, Hispanic, and Anglos.” Through making these complex and interwoven works, Neshat formed a deep interpersonal connection with each. To complement this important installation, the exhibition at MOCA also includes two of Neshat’s seminal films “Roja” (2016) and “Rapture” (1999), as well as photographs from the series “Women of Allah” (1993-1997), introducing the expanse of her work to a new generation of audiences in Canada.

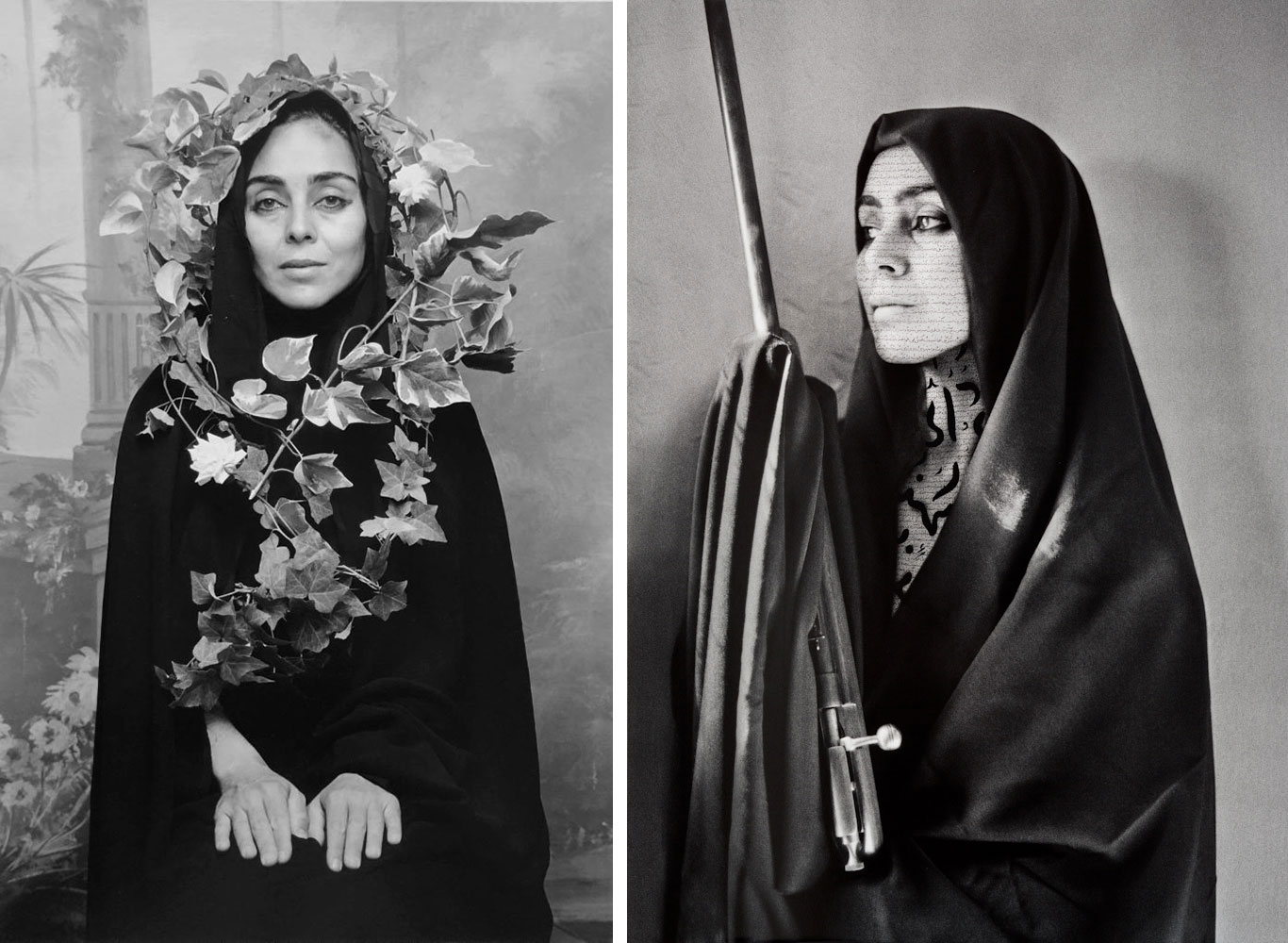

“Roja” (2016), drawn from Neshat’s own recurring dreams, memories, and desires, traces an Iranian woman’s disquieting attempts at connection with American culture while reconciling her identification with her home country. Encountering her own sense of alienation from both, the titular protagonist experiences how both the foreign and the familiar can become unnerving and hostile. Neshat undermines Roja’s social and affective attachments—from a cabaret performance that becomes a nightmarish challenge to her identity, to a recovery of familial bonds that turns increasingly frightening. Throughout the film, she estranges American landscapes—the utopic attempts of government architecture and coalmines that evoke the terrain of the Middle East—to situate Roja within an ambiguous psychic and political terrain. Using nonlinear narratives and destabilizing in-camera techniques, the film questions the relationships that tie us to the world and reveals the transcendence of release into spaces unbounded by socio-historical demarcations. “Rapture” is an installation of two synchronized black-and-white video sequences that are projected on opposite walls; large in scale, they evoke cinema screens. Working with hours of footage and a team of editors, the artist constructed two parallel narratives: on one side of the room, men populate an architectural environment; in the other sequence, women move within a natural one. The piece begins with images of a stone fortress and a hostile desert, respectively. The fortress dissolves into a shot of over one hundred men—uniformly dressed in plain white shirts and black pants—walking quickly through the cobblestone streets of an old city and entering the gates of the fortress. Simultaneously, the desert scene dissolves into a shot of an apparently equal number of women, wearing flowing, full-length veils, or chadors, emerging from different points in the barren landscape. As the video progresses, the men busy themselves with a variety of mundane, sometimes absurd activities that contradict the intended function of the space. On the other side of the installation, the women chant, pray, and later, having made their way across the desert, launch a boat into the sea with six of their own aboard. In Rapture, Neshat self-consciously exploits entrenched clichés about gender and space: namely, the equation of woman with irrational, wild nature and man with rational, ordered culture. The video installation is itself a study of gendered group dynamics, with the viewer literally positioned between two opposing worlds. The players in Neshat’s surreal, segregated narratives are deployed in a syncopated rhythm of action and nonaction, mutual recognition and nonrecognition, advance and retreat. “Women of Allah” is a series Neshat worked on from 1993 to 1997, investigating the complexity of the women’s lives in Iran after the Islamic revolution. In sharp black and white, which would become one of the hallmarks of her photography, Neshat portrayed Iranian women veiled and often wielding firearms. The few areas of skin left uncovered by the chador – face, hands and, more rarely, feet – are covered with inscriptions in “Farsi” (Persian). Taken from the books of Iranian writers, the inscriptions interact with the images to give them a more complex meaning; prose and poetry are often combined, and the contents range from religious to more profane subjects, exploring the spheres of intimacy and sexuality. The image of women in Islamic culture is thus rendered in all its complexity and ambiguity, represented in the duality of the roles that post-revolutionary Iranian society assigns them: on the one hand the restrictions imposed by rigid religious dictates; on the other the paradoxical condition that seeks to make women responsible and committed (see the presence of guns). Neshat’s gaze avoids judgment to focus on the many cultural, social and psychological facets of these figures.

Photo: Shirin Neshat, All Demons Flee, from Women of Allah Series, 1995, LE gelatin silver print (photo taken by Bahman Jallali), Work: 115 x 166 x 4.8 cm, © Shirin Neshat, Courtesy the artist and MOCA-Toronto

Info: MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art), 158 Sterling Road, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Duration: 10/3-31/7/2022, Days & Hours: Wed-Thu & Sat-Sun 11:00-18:00, Fri 11:00-21:00, https://moca.ca

Right: Shirin Neshat, Katalina Espinoza, from Land of Dreams series, 2019, Digital c-print with ink and acrylic paint, 47 x 31 1/4 inches (119.4 x 79.4 cm), © Shirin Neshat, Courtesy the artist and MOCA-Toronto

Right: Shirin Neshat, Simin, from Land of Dreams series, 2019, Digital c-print with ink and acrylic paint, 81 x 54 inches (205.7 x 137.2 cm), © Shirin Neshat, Courtesy the artist and MOCA-Toronto

Right: Shirin Neshat, Isaac Silva, from Land of Dreams series, 2019, Digital c-print and acrylic paint, 60 x 40 inches (152.4 x 101.6 cm), © Shirin Neshat, Courtesy the artist and MOCA-Toronto