ART CITIES:Zurich-Chase Hall

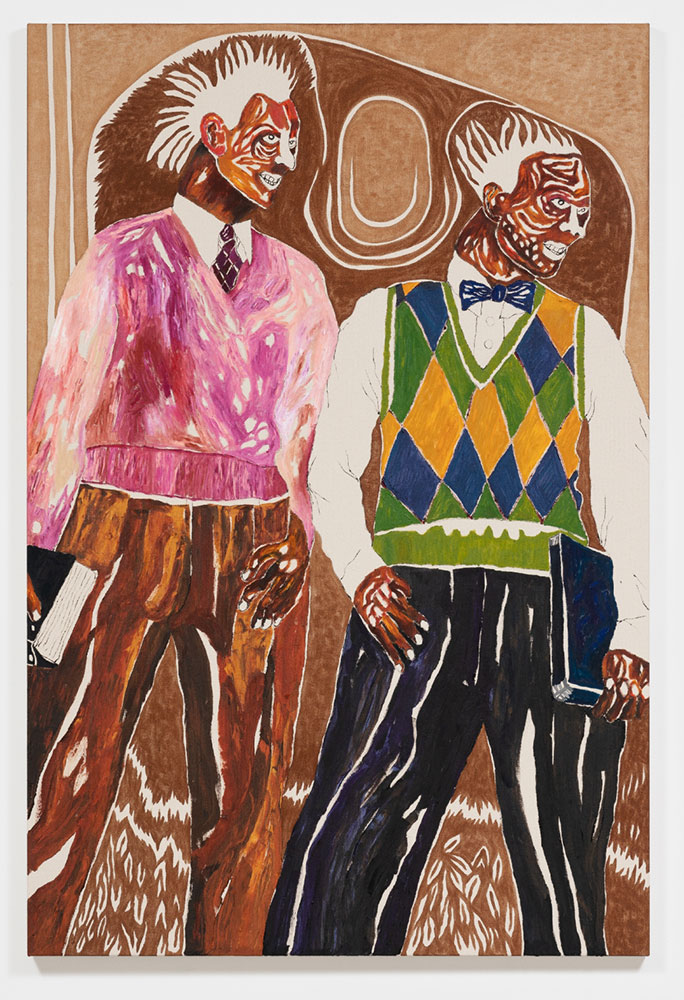

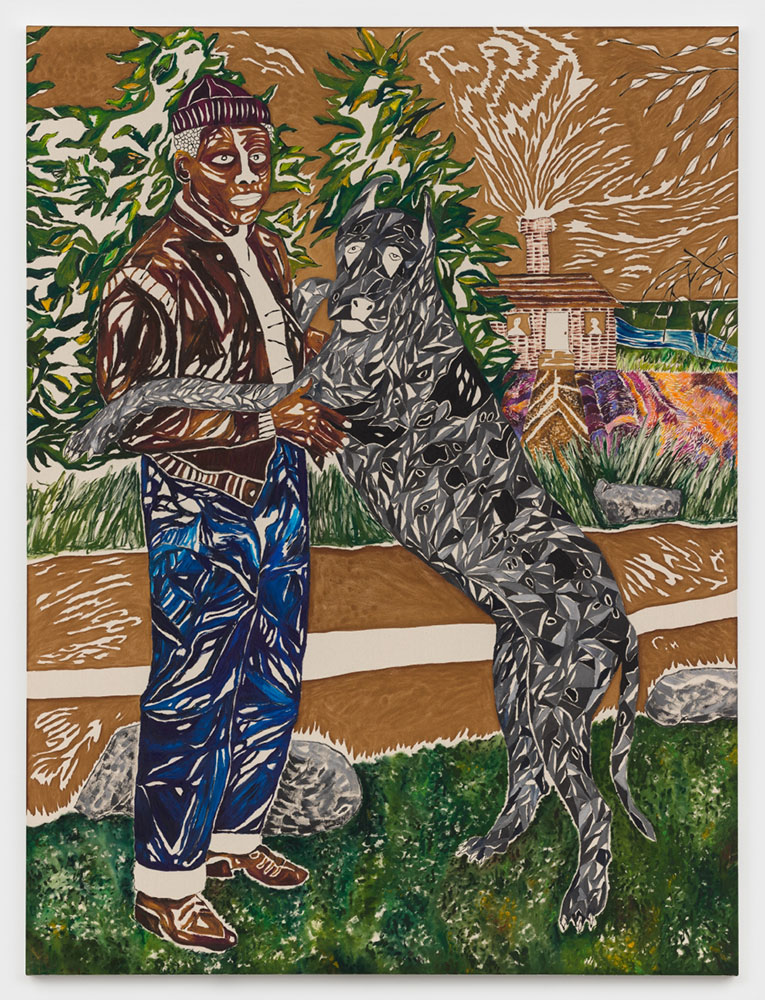

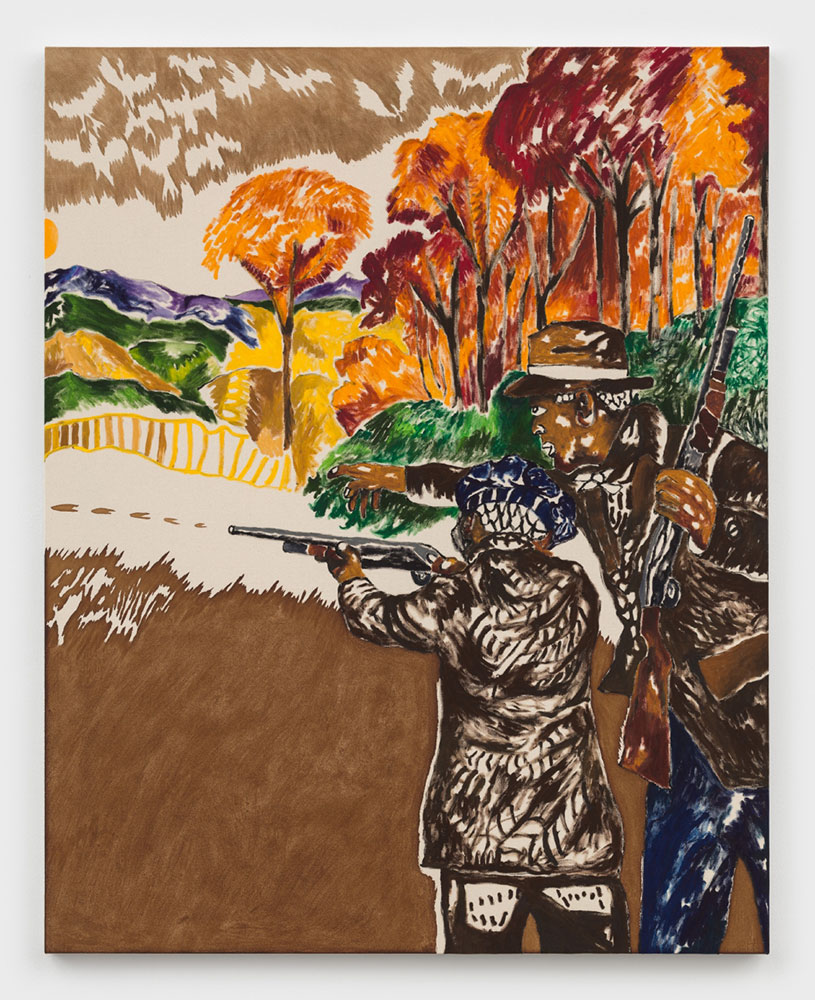

A self-trained artist, Chase Hall works in painting, sculpture, photography, video, and audio to scrutinize America’s past and present while interrogating the realities of being biracial. As a mixed-race male raised across America, Hall examines humanity through his individual hybridity and his usage of coffee as a pigment and cotton canvas as a conceptual white paint. Each canvas is imbued with the legacy of Hall’s personal history and a non-monolithic Black experience.

A self-trained artist, Chase Hall works in painting, sculpture, photography, video, and audio to scrutinize America’s past and present while interrogating the realities of being biracial. As a mixed-race male raised across America, Hall examines humanity through his individual hybridity and his usage of coffee as a pigment and cotton canvas as a conceptual white paint. Each canvas is imbued with the legacy of Hall’s personal history and a non-monolithic Black experience.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Galerie Eva Presenhuber Archive

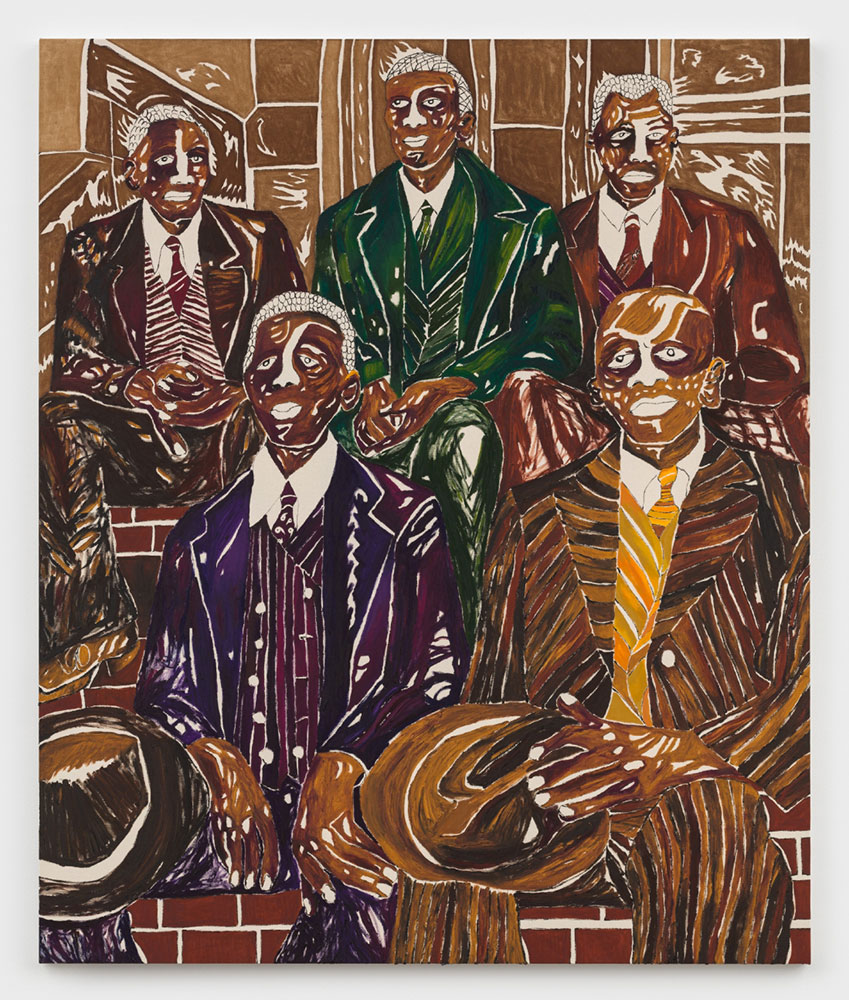

Chase Hall presents his solo exhibition “Clouds in My Coffee” in Galerie Eva Presenhuber. Growing up mixed-race and too-grown in spaces no child should be, Hall became all-too-conversant all-too-early with the national psychosis of race and desire. But rather than drowning in lifelong phenomenologies of anger, Hall turned to making and reading and music. His autodidact studies were fluid and unbounded by categories of knowledge, allowing Hall to forge his own ethics of attention. Rather than pursue a formal arts education, he used a nearby art school’s trash. As the departing students left their materials behind after each semester, he appropriated the discarded stretcher bars and partially-used tubes of paint. With these supplies, new cotton canvas, and the inventive use of brewed coffee grounds as a pigment, Hall has produced a powerful, art historically significant body of work that addresses a wide range of socio-cultural issues, from the complexities of race, the weighty histories of coffee and cotton and the ways they are interwoven with the transatlantic trade, a myriad of other specific cultural references and personages as subject matter, and personal meditations on his own place in society. In painting’s visual typologies, Hall discovered gestural kinship with jazz prosody and critical theory, and he leveraged his fluency to reframe the structures of America’s dream deferred into a viable, self-reliant future of beauty and purpose. But an artistic life never goes uncontested. Especially when your skin is material memory and your very being amplifies the political stakes of your personal practice. For all the recent talk of decolonizing and disavowing “the canon,” we rarely admit that American art for the past century has multiple canons: the canon of black figuration which proclaims baroque-era presence, and the Eurocentric modalities of modernism that connote aspiration, mastery, and power, being merely the most dialectically-opposed. From which tradition does the young artist draw inspiration when life evinces dual citizenship in both worlds? What material can hold the simultaneous sepia-like vignette of colonial trauma and light-skinned privilege that frames an artist’s being and becoming? Half-and-half, with 20/20 vision, Hall is still no more than three-fifths a man in the eyes of the law. What materials are historic enough, durable enough, suffuse and itinerant enough, to visually-represent grace at, and beyond borders? In Chase Hall’s orchestral compositions of acrylic and coffee on unprimed cotton canvas, coffee and cotton foreclose the ease of reaching for binaries of white and black, good or bad, when we stand before them as viewers, and as heirs to art history’s omissions and fixations around black and brown bodies; including the necessary commodities the labor of those bodies provide. Like silk, like sugar and indigo, like the saltlick of tears from human bodies, coffee unites the four corners and belly of the world. Whether we drink it is immaterial. Coffee, like the acerbic aftertaste of enslavement, is inseparable from modernity. Coffee’s deep painterly soak into the absorbent fibers both balances and counteracts the loose, intuitive brushwork of Hall’s hand by adding a bit of chance and abstraction to deftly-modeled scenes. But raw cotton has fibrous teeth. And in syncopated breaks of whiteness, the canvas holds coffee’s sweep at bay, pooling the brew in some zones, and not others. In these rhythmic uncolored passages of void and lacuna, the white fibers trick the eye into thinking absence is a presence. In these instances where raw cotton asserts its white vacuity, Hall activates the liminal correspondence between whiteness and everything else. By enticing the viewer to look closer and to understand, Hall is challenging the viewer’s assumptions about material capacity and by extension, binary racial constructions. The globular dimensionality of the acrylic pigments rests on the surface of the mosaic ground like a marble, serving as a opaque resist to the gouache effect of the coffee and symbolizing the knuckled muck of the present and the ambivalent, if dogged hope black and brown peoples have in a future of their own imagining. Hall has managed to do what the impressionists are revered for 180 years later: he has found a way to make history and material molten, airy, and poetic. He has found a way to turn the dark shadow of shame in hyper/invisibility toward the light. And he did not have to dilute coffee’s power with sugar or cream to do so.

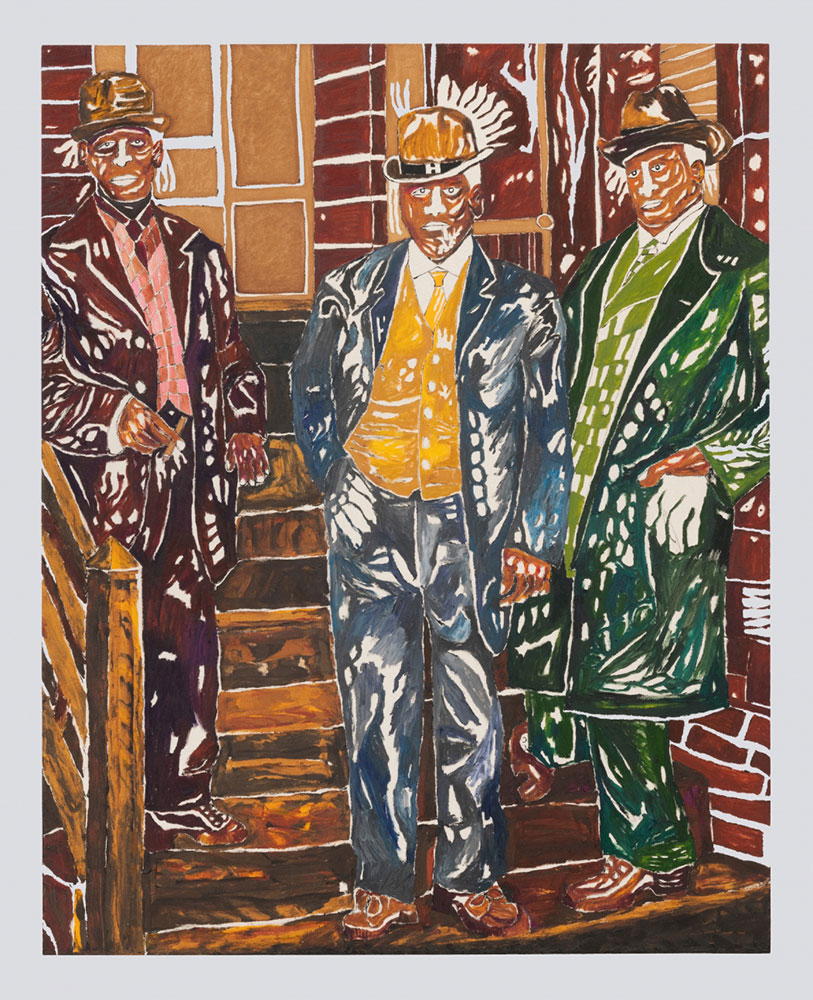

Photo Left: Chase Hall, the family was all around me, 2020, Acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 183 x 152.5 cm / 72 x 60 in, © Chase Hall, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber. Right: Chase Hall, The Ocean’s Floor, 2021, Acrylic and coffee on cotton canvas, 183 x 152.5 cm / 72 x 60 in, © Chase Hall, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber

Info: Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Waldmannstrasse 6, Zurich, Switzerland, Duration: 5/3-9/4/2022, Days & Hours: Wed-Fri 12:00-18:00, Sat 11:00-17:00, www.presenhuber.com