ART CITIES: Berlin-Peter Friedl

Peter Friedl’s practice eludes unequivocal media- and style-specific attributions. A recurring element in his oeuvre is a highly specific mode of approach. Rather than showing dedication to particular topics or stylistic principles, Friedl’s works, which often touch on politically charged issues follow an aesthetic strategy of “radical neutrality”. Instead of arguing for a certain reading or interpretation of a cultural or political artefact, Friedl explores the social and media-specific conditions under which these readings, interpretations, and meanings become established. In this sense, his works are not so much theses but rather exemplary models for the renegotiation of political and historical certainties.

Peter Friedl’s practice eludes unequivocal media- and style-specific attributions. A recurring element in his oeuvre is a highly specific mode of approach. Rather than showing dedication to particular topics or stylistic principles, Friedl’s works, which often touch on politically charged issues follow an aesthetic strategy of “radical neutrality”. Instead of arguing for a certain reading or interpretation of a cultural or political artefact, Friedl explores the social and media-specific conditions under which these readings, interpretations, and meanings become established. In this sense, his works are not so much theses but rather exemplary models for the renegotiation of political and historical certainties.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: KW Archive

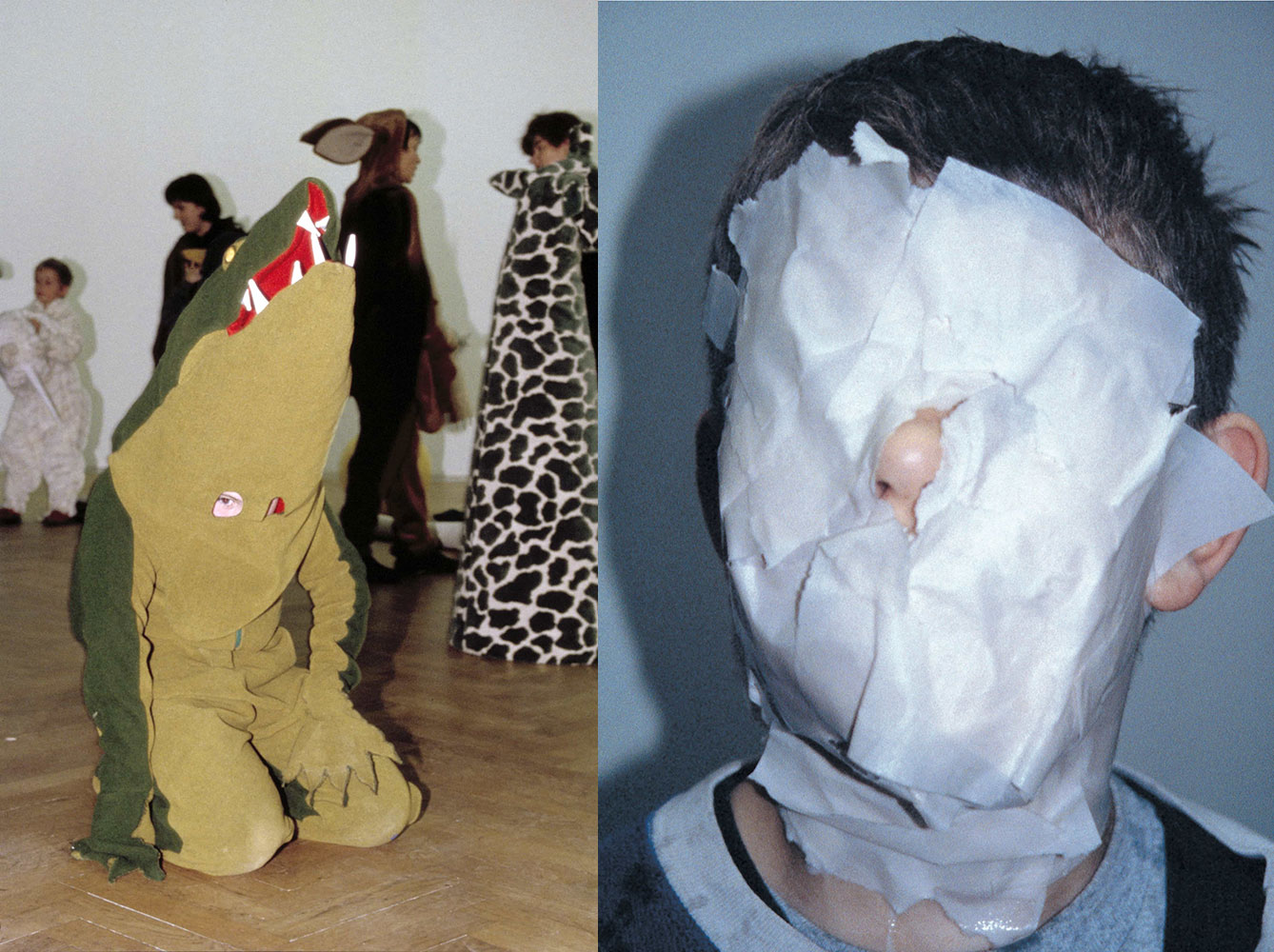

Report 1964–2022” is Peter Friedl’s most extensive institutional survey in Germany to date. Adopting a variety of genres, media, and forms of display, Friedl’s works seek to explore the construction of history and the concepts within our political and aesthetical consciousness. His artistic practice is aimed at creating new models of narration in which time, permanent displacement, and critical intimacy all play a central role. Friedl often refers to and employs theatrical representation and poetics in his works (e.g., scale models, tableaux vivants, props, puppet theatre, restaging) to highlight hidden or overlooked mechanisms intrinsic to historiography, language, and cultural identities. Archival rigor is the key organizational strategy behind some of his long-term projects, which have strict chronology and other principles of order call into question notions of visibility and context. Drawing as a lyrical voice, which documents and comments on both personal and socio-political histories, is equally important in Friedl’s oeuvre. As a monographic exhibition, “Report 1964–2022” brings together works from five decades. Its title stems from an eponymous video installation that Friedl created for documenta 14, which explores the permeability of language and the boundaries of identity. Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are facing three custom-made showcases filled with stacks of diaries. “The Diaries” (1981–2022) contains thousands upon thousands of densely filled hand-written pages covering each day over a period of forty years and testifying the futility of capturing a life in words. By denying access to the contents of his enshrined, closed diaries, Friedl invites the viewer to contemplate how aesthetic experience and imagination work. Early photographic collages from 1971 can be seen as Friedl’s first attempt at photography, in which he juxtaposes found imagery and text, in this case from the fantasy world of Native American people. The video “Untouched” (1995–1997) features Friedl’s first son popping balloons that have the slogan “Nobody knows science” printed on them. The footage was taken in Berlin and Italy over a period of two years. “New Kurdish Flag” (1994–2001) uses color as a means to reflect on a concrete object—the flag (and logo) of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)— and its political history as a symbol of resistance. The flag’s original red colour has been brightened to pink; the programmatic star in the center is cut out and missing. “Playgrounds” (1995–2021) is one of Friedl’s longterm projects showing documentary-style photos of play areas taken by the artist around the globe. The pictures play with the genre of conceptual photography and research underscoring urban typologies of modernist planning, which can be interpreted as a remnant of twentieth-century utopias. While place and time are stated, the distanced view (always through the same analogue camera), which favours aesthetics over functionality, emphasizes their apparent similarities and diversity. The work contains over 1,200 digitized color slides arranged alphabetically according to the location names. The notion of scale and model play a pivotal role in Friedl’s artistic practice. “Rehousing” (2012–2019) is presented in two rooms and consists of 12 true-to- scale models that reproduce historical, sometimes destroyed, or never realised housing structures. The first model (Gründbergstraße 22, 2012) is the artist’s childhood home in Austria; following models comprise of Ho Chi Minh’s private residence, a traditional stilt house structure in Hanoi (Uncle Ho, 2012); a slave hut on the Evergreen plantation established in Louisiana in the eighteenth century (Evergreen, 2013); a never realized residential building in the razionalismo style designed by Luigi Piccinato for East Africa during the Fascist era (Villa tropicale, 2012–13); a replica of philosopher Martin Heidegger’s cabin in the Black Forest (Heidegger, 2014); a reconstruction of a shack built by African refugees in Berlin and taken down by the police in 2014 (Oranienplatz, 2014); a so-called “nail house” or dingzihu—representing one of many local structures resisting the Chinese building boom (Holdout, 2016); and one of the few derelict buildings left from Van Molyvann’s 100 Houses project completed in 1967 for employees of National Bank of Cambodia in Phnom Penh (101, 2016). The dome construction is from Drop City, the short-lived hippie commune founded in Southern Colorado in 1965 and abandoned in the mid-1970s, which implemented Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic design principles into DIY buildings (Dome, 2016); a container home comes from a refugee camp in Jordan (Azraq, 2016). The two most recent models show Winnie and Nelson Mandela’s former home in Soweto, now transformed into a museum (8115 Vilakazi Street, 2018–2019) and one of the prefabricated container houses that made up Amona—the Israeli outpost in the Palestinian territories on the West Bank, which was cleared in 2017 (Amona, 2018–2019).

Walking down into main hall, the visitor encounters four delicately handcrafted marionettes standing on the ground and hanging on their strings from the gallery ceiling. The “Dramatist (Black Hamlet, Crazy Henry, Giulia, Toussaint)”(2013) embodies the figures of Toussaint Louverture, the multi-faceted leader of the Haitian Revolution in 1791, who helped shape the first independent nation in the Caribbean; Henry Ford, the automobile magnate from Detroit, who perfected mass production; Giulia Schucht, the wife of Antonio Gramsci; and John Chavafambira, a Manyika nganga (healer- diviner) who moved from his home in Zimbabwe to Johannesburg in the late 1920s and became the subject of the novelistic narrative Black Hamlet (1937) by South African psychoanalyst Wulf Sachs. By bringing these four characters together, Friedl opens new possibilities for reflection on how historiography is being constructed. On the opposite walls, there is a selection of more than 150 drawings created by the artist between 1964 (when Friedl was four years old) and late 2021. The long timeline that binds them together doesn’t feign any chronology. The central space of the main hall hosts two of Friedl’s most prominent works: “Theory of Justice” (1992–2010) and “Report” (2016). The title “Theory of Justice” refers to the attempt at renewing social contract theory undertaken in the early 1970s by US philosopher John Rawls. Friedl adheres to a rigid system of newspaper and magazine clippings collected over the course of roughly two decades and displayed in specifically designed showcases following solely the chronology of the documented, depicted events. By omitting any further information on context and time, Friedl creates a new narrative of protest and resistance, that is based purely on imagery and selection. Cinematographically “Report” (2016) is perhaps the most complex of Friedl’s film installations. The source text is “A Report to an Academy” (1917), Franz Kafka’s short story about Red Peter, an ape who reports on his experience of becoming human. Set in the National Theatre in Athens24 performers—mostly amateur actors—appear on stage and recite extracts from Kafka’s monological text, either in their own first languages or in languages of their choice, including Arabic, Dari, English, French, Greek, Kurdish, Russian, and Kiswahili. German, the text’s original language, and subtitles are deliberately left out. What unites the people on stage are their physical presence, gestures, speech, and the fact that many of them came to Greece in the wake of recent immigration movements. “No prey, no pay” (2018–19) is a continuation of Friedl’s long-standing interest in looking at outcast and marginalised positions differently and within. As a starting point, the theatrical installation refers to the heyday of piracy between the 1650s and the 1730s. “No prey, no pay” consists of a cast of distinctive fringe characters whose fascinating biographies are situated somewhere between reality, fiction, and legend. To each of these characters, Friedl dedicates a colourful plinth or pedestal like those used in a circus, beneath an apocryphal Jolly Roger (entitled King Death), with pirate costumes lying around. The pedestals are both sculptures and tiny stages, reminiscent of Speakers’ Corners, waiting to be activated.

Info: Curator: Krist Gruijthuijsen, Assistant Curator: Léon Kruijswijk, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Auguststraße 69, Berlin, Germany, Duration: 19/2-1/5/2022, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 11:00-19:00, Thu 11L00-21:00, www.kw-berlin.de