ART CITIES: N.York-Charles Ray

For over five decades, Charles Ray has experimented with a wide range of methods, including performance, photography, and sculpture, the medium for which he is best recognized today. In the process, he has utilized a variety of materials, expanded the fundamental terms of sculptural language, and pioneered major advances in production, combining the analog and the digital as well as human and robotic hands. Additionally, Ray’s work addresses in elliptical, often irreverent ways not only art history, popular culture, and mass media but also identity, mortality, race, and gender.

For over five decades, Charles Ray has experimented with a wide range of methods, including performance, photography, and sculpture, the medium for which he is best recognized today. In the process, he has utilized a variety of materials, expanded the fundamental terms of sculptural language, and pioneered major advances in production, combining the analog and the digital as well as human and robotic hands. Additionally, Ray’s work addresses in elliptical, often irreverent ways not only art history, popular culture, and mass media but also identity, mortality, race, and gender.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: MET Archive

The exhibition “Figure Ground” presents sculptures from every period of Charles Ray’s work with key photographs from the 1970s and 1980s, exploring central aspects of his challenging and sometimes provocative oeuvre. It also brings together for the first time all the works that Ray loosely patterned on Mark Twain’s 1885 novel “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. Throughout his career, Ray has expanded the fundamental terms of sculptural language. Long engaged with the history of Western sculpture, his work self-consciously reinvents traditions associated with the past, from classicism to Minimalism. Ray has also experimented with an astonishing variety of materials, from fiberglass and porcelain to wood, aluminum, and steel, and pioneered major advances in production, combining the analog and the digital as well as human and robotic hands. His work addresses in elliptical, often irreverent ways not only popular culture and mass media but also identity, mortality, race, and gender. From the beginning of his career, Ray has been acutely aware of the myriad ways in which the body is implicated in the form and meaning of sculpture. His interest in indexing his own body, whether as organic matter or as structural dimensions, can be traced to works such as “Untitled” (1973) realized while he was a student at the University of Iowa. The photograph documents a performance in which the artist had himself trussed up and tied to a tree for several hours, hovering above passersby. Ray’s silhouetted figure appears entangled in the branches and dangerously suspended in midair. Straddling satire and gravity, the work presents as an audacious prank as well as a more disquieting confrontation with a body in extremis. In “Table” (1990) the setup for a painterly still life is transformed into a sculptural meditation on the conditions of space. The work deftly yokes the transparency and permeability of the bottomless vessels with the opacity and solidity of the tabletop in which they are embedded. Overall, it presents as a unified object through which the eye can travel and space can flow unimpeded, at least until arriving at the lid of a cotton jar. This subtle interruption serves as a perceptual short circuit, bringing the deliberate spatial arrangements into focus. The work follows a series in which Ray used the simple structure of a table as a site for exploring the complex sculptural dynamics of utilitarian objects. While these earlier iterations relied on the juxtaposition of items in a range of materials and occasionally included kinetic elements, here, all excess is expunged, distilling the relationship between forms and space into a liminal composition.

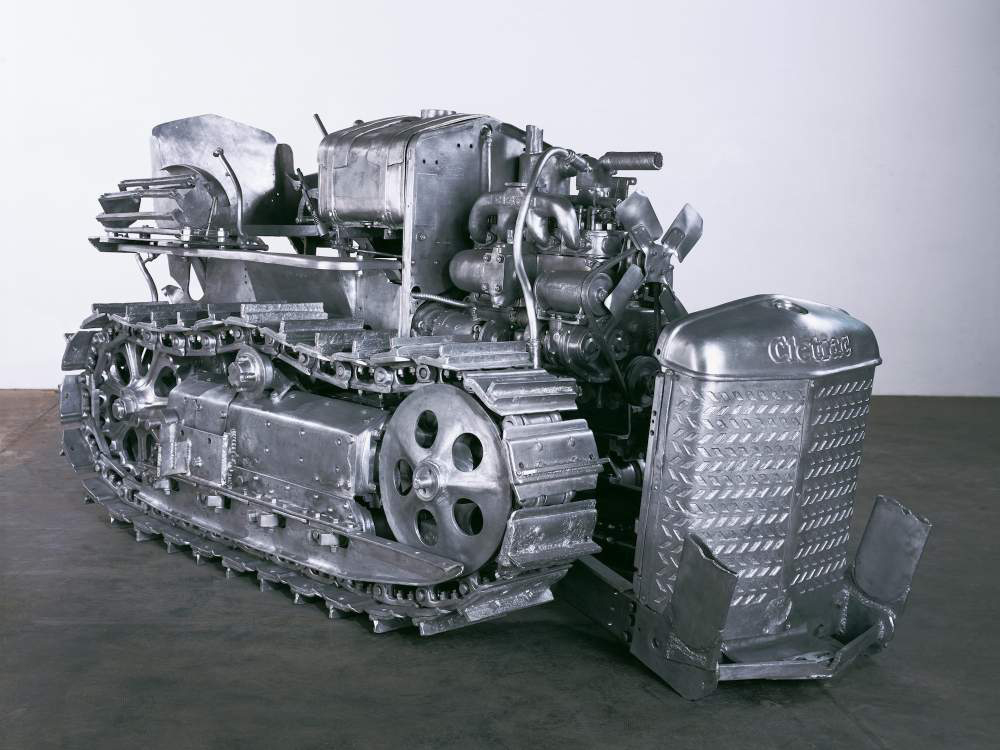

Although “Family romance” (1993) relies on the technology of mannequin making, Ray considers it one of his earliest sculptures of figures. The title alludes to a 1909 essay by Sigmund Freud on intrafamilial conflict as well as to the slogan “family values,” instrumentalized by President George H. W. Bush in the early 1990s. The sculpture, which Ray has called “an abstraction of a relationship of parts,” parodies the archetype of the heteronormative family. Its four figures with interlocked hands read like a chain of three-dimensional paper dolls. All are the same height, making them either too tall or too short for their age. The overall composition is strict, repetitive, and modular. Logic bests passion, while mechanical reproduction trumps procreation. In its dramatization of artificiality, Family romance also decouples the human and the “natural,” disassociating sex, gender, and race from biology. Ray’s sculptures are often loosely patterned on preexisting ideas and things. Such is the case with “Tractor” (2005) which takes as its point of departure a boyhood memory and, more directly, an abandoned vintage tractor found in the San Fernando Valley, California. In order to sculpt the entire vehicle inside and out, Ray had the original retrieved and disassembled. Studio assistants modeled each part in clay, creating representations that retain evidence of their makers’ hands. After molds were taken and waxes created, the elements were cast in aluminum and reassembled to make a complete, topological object that is both relic and reliquary. With its uniformity of color, patina, and material as well as its semireflective surface, Tractor asserts its abstract qualities. The composition of “Boy with a Frog” (2009) is a precise arrangement of forms: a nude young boy, with back arched and tummy thrust forward, tilts his head and gazes blithely at a frog dangling precariously, even cruelly, from his outstretched arm. The sculpture was commissioned by François Pinault for the exterior of the Punta della Dogana, a bustling civic space along the Grand Canal in Venice. The work’s riverine associations persist beyond its original location, loosely recalling the tales of Huckleberry Finn that unfold along the shoreline of the Mississippi. With its stance suggesting both outward inquiry and self-absorption, Boy with frog also reflects Ray’s sculptural engagement with the formative conditions of boyhood, in which a sense of the world may be grasped through curious and sometimes callous play.

Full of gravitas and portent, “Huck and Jim” (2014) interprets a moment in Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”, when the protagonists debate the origin of the stars while floating down the Mississippi River on a raft. The figures are about twice life-size and are shown in a state of acute absorption. Youthful and curious, Huck bends forward to scoop an invisible object off the ground. Stoic and self-possessed, Jim stares into the distance, his hand hovering over Huck’s back. Twain’s characters are often not wearing clothes in the novel. Ray, who has been exploring the nude figure since the 1980s, thought nudity also suited the sculpture, which was originally conceived for a fountain outside the Whitney Museum of American Art. What signals freedom and homosociality in the book introduces the troubling possibility of transgenerational desire in the sculpture, bringing about what Ray has described as a “layered dynamic”. “Mime” (2014) was produced via a circuitous process that began with three-dimensional digital scans of a human model and ended with the machining of commercial-grade aluminum. A male figure—modeled on professional mime Lorin Eric Salm—lies on a cot with his chest slightly inflated, suspended in space and time. Illusion is fundamental to the art of miming as well as the sculpture itself. Indeed, Ray’s work self-consciously addresses the imitative ability of both its subject and its medium. Mime also leaves the figure’s precise comportment open to interpretation, resulting in a dizzying array of potential readings. The sculpture might represent a mime who is sleeping, a mime who is miming sleep, or a mime who is miming the onset of death. In fact, the figure’s raised arm recalls historical sculptures of mortally wounded or deceased warriors. “Archangel” (2021) was conceived for an exhibition in Paris. Shocked by terrorist attacks like the one that occurred in the offices of Charlie Hebdo in 2015, Ray envisioned the archangel Gabriel, a guardian figure in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, alighting onto unstable ground. This initial inspiration was subsequently filtered through what the artist has called a “tangled heap” of personal and cultural references, including “illustrations from primary-school catechism textbooks.” In the final work, the title is the only direct trace of the original idea. The sculpture was carved from Japanese cypress (hinoki) in Osaka by expert woodworker Yuboku Mukoyoshi and his apprentices using a single block of laminated timber. An adult male figure perches precariously but gracefully atop a simple box. Like much of Ray’s work, Archangel crisscrosses the historical and art historical timeline. While the figure’s exposed torso and outstretched arms evoke a Christian crucifixion scene, his rolled-up pants, flip-flops, and man bun identify him with the contemporary moment.

Photo: Charles Ray, Mime, 2014, Aluminum, 25 . × 77 . × 29 in. (64.8 x 196.2 x 73.7 cm), Hill Charitable Collection, © Charles Ray, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Info: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Met Fifth Avenue, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, USA, Duration: 31/1-5/6/2022, Days & Hours: Sun-Tue & Thu 10:00-17:00, Fri-Sat 10:00-21:00, www.metmuseum.org

Right: Charles Ray, Huck and Jim, 2014, Stainless steel, 9 ft. 3 . in. × 54 in. × 53 . in. (283.2 x 137.2 x 136.5 cm), Collection of Lisa and Steven Tananbaum, © Charles Ray, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Right: Charles Ray, Boy with frog, 2009, Painted stainless steel, 96 x 29 . × 41 . in. (243.8 x 74.9 x 104.7 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Promised gift of Keith L. and Katherine Sachs, © Charles Ray, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery