TRACES: Joseph Kosuth

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist and theoretician, a founder and leading figure of the Conceptual Art Movement Joseph Kosuth (31/1/1945- ). He is known for his interest in the relationship between words and objects, between language and meaning in art. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the American artist and theoretician, a founder and leading figure of the Conceptual Art Movement Joseph Kosuth (31/1/1945- ). He is known for his interest in the relationship between words and objects, between language and meaning in art. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

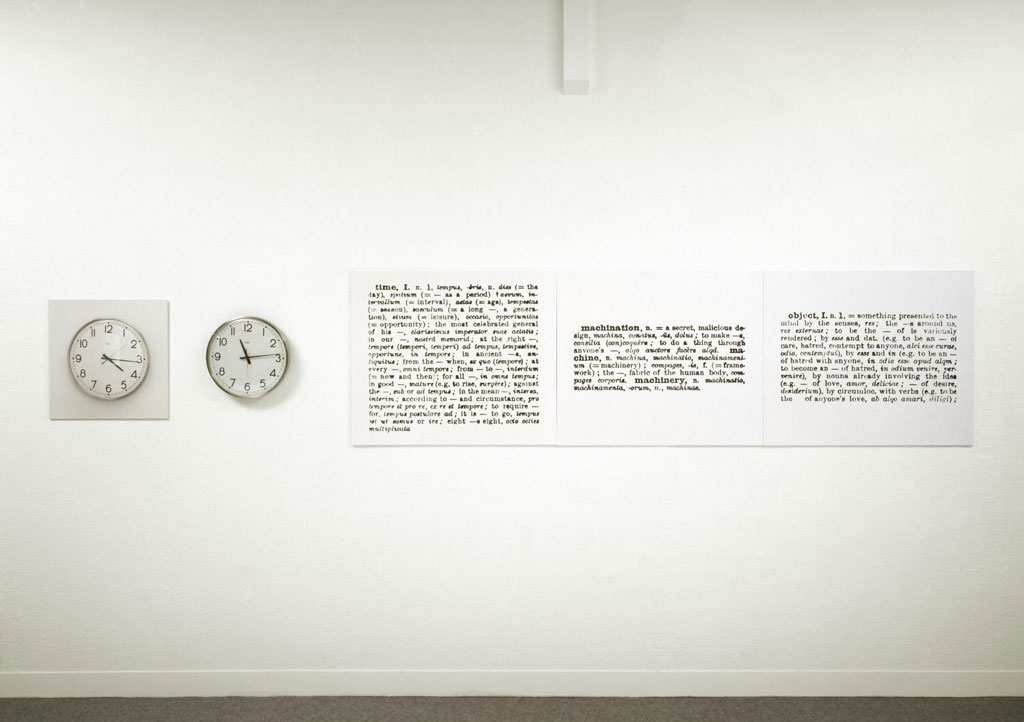

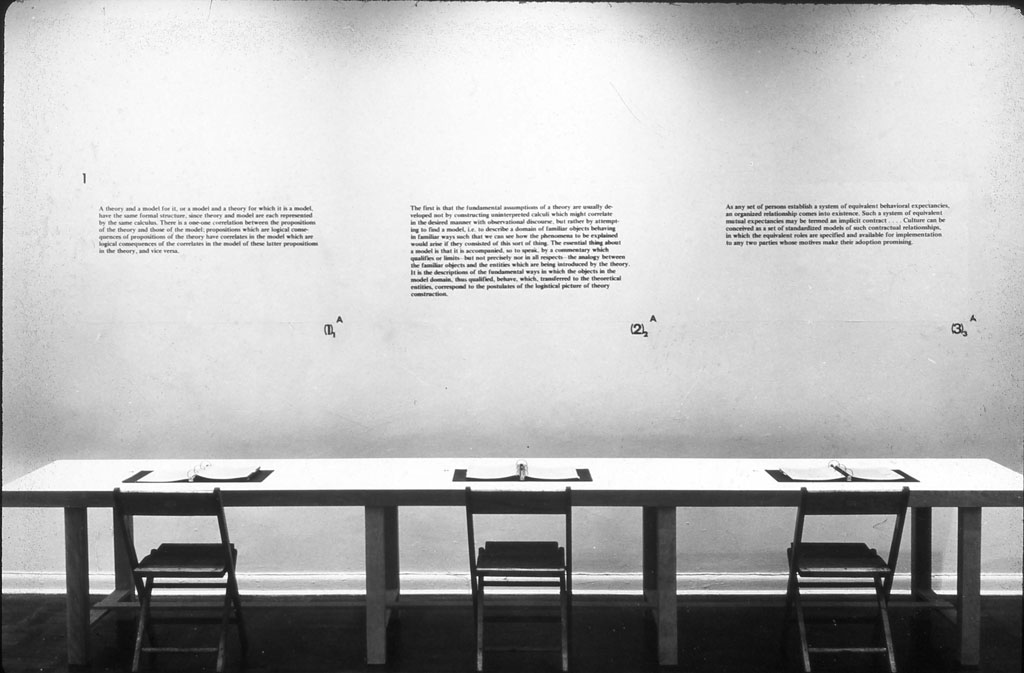

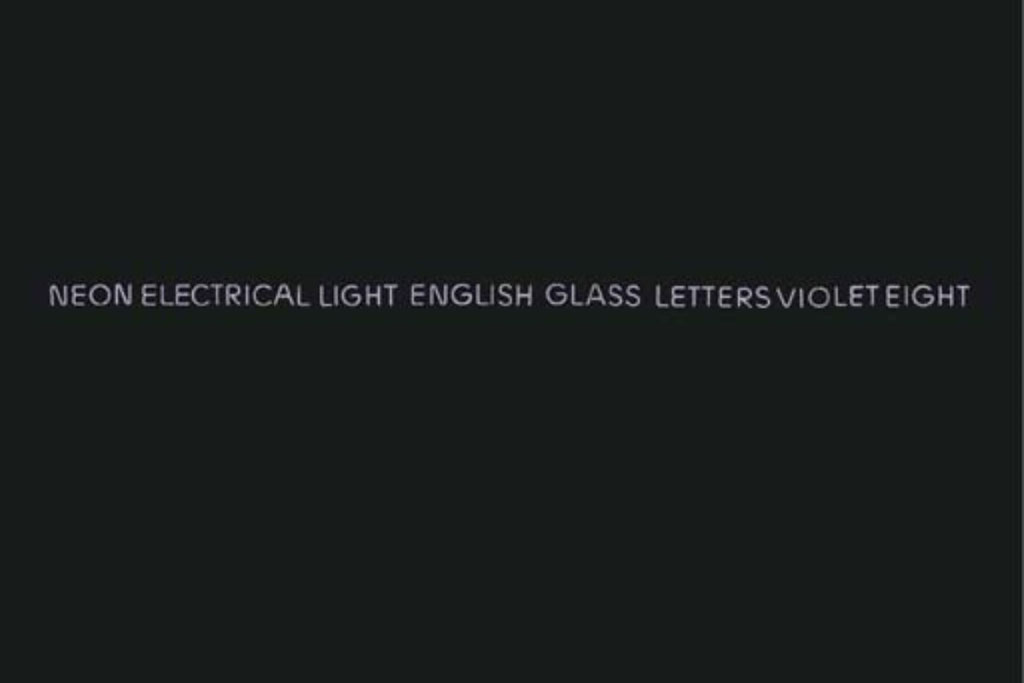

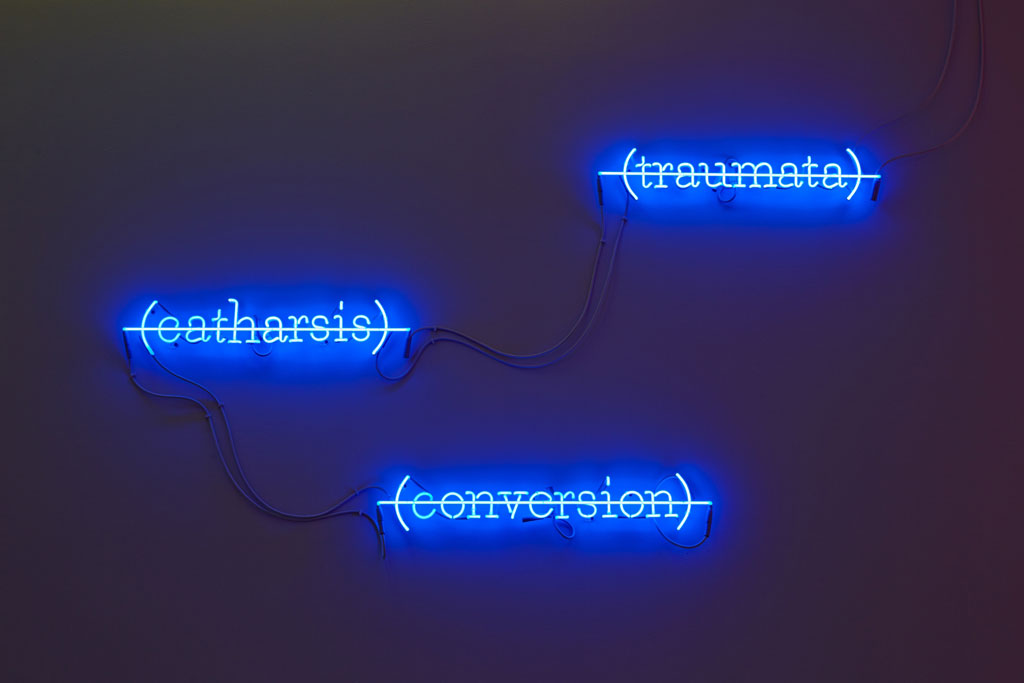

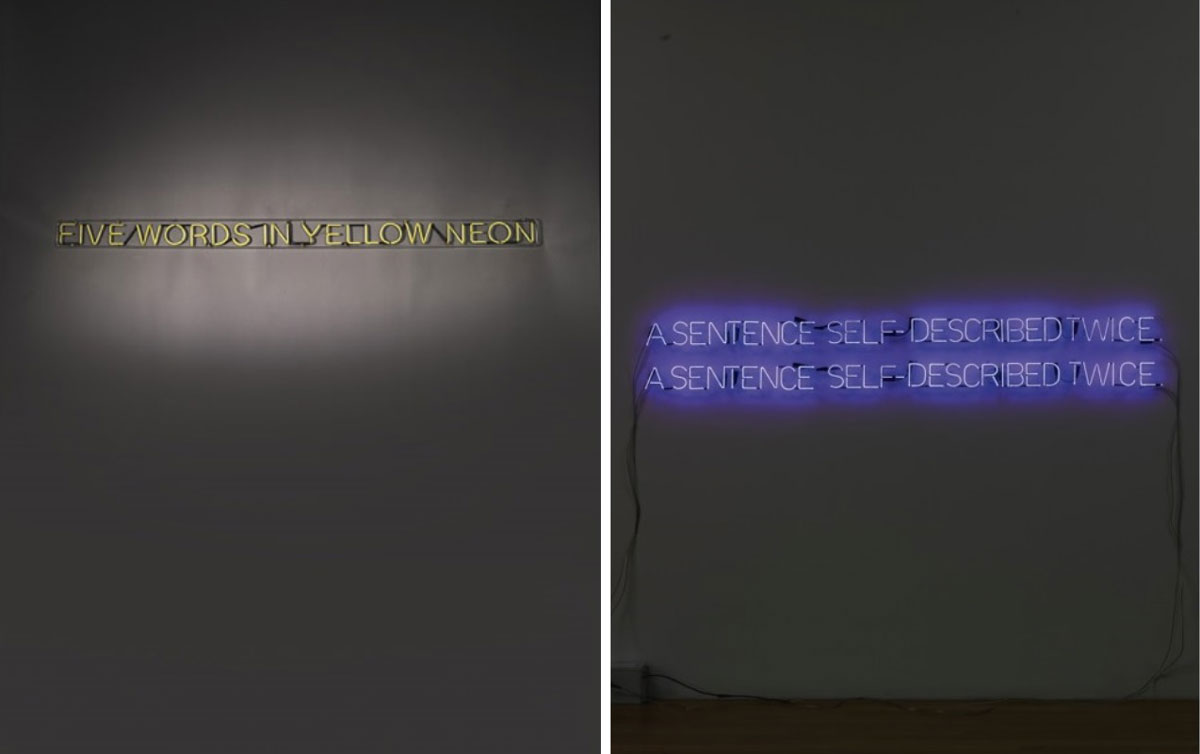

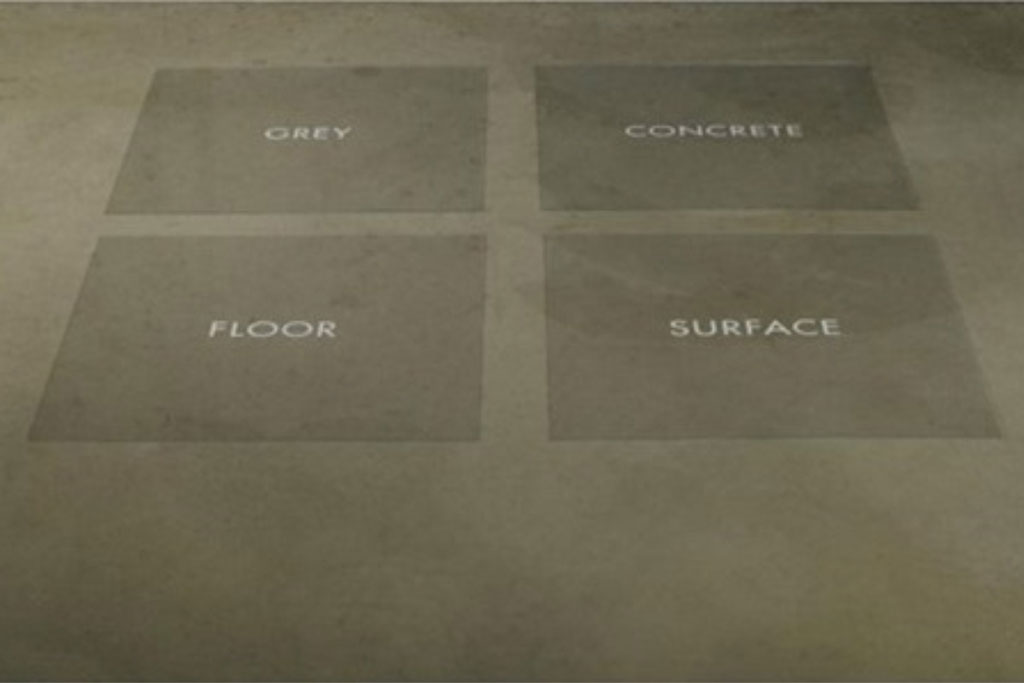

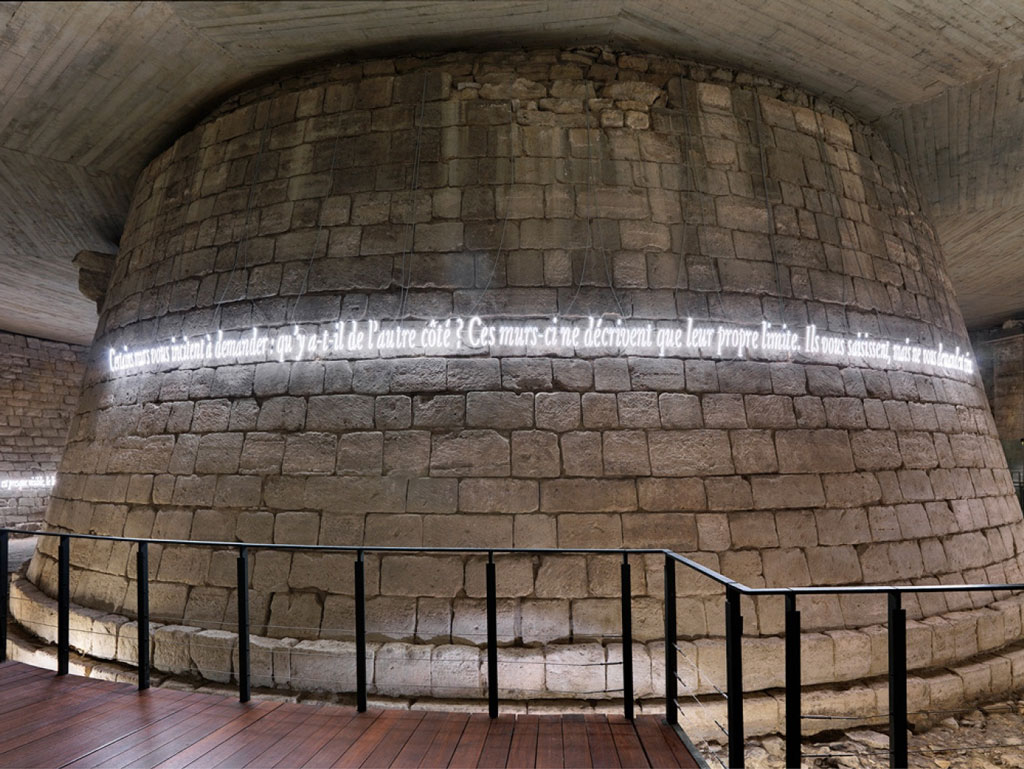

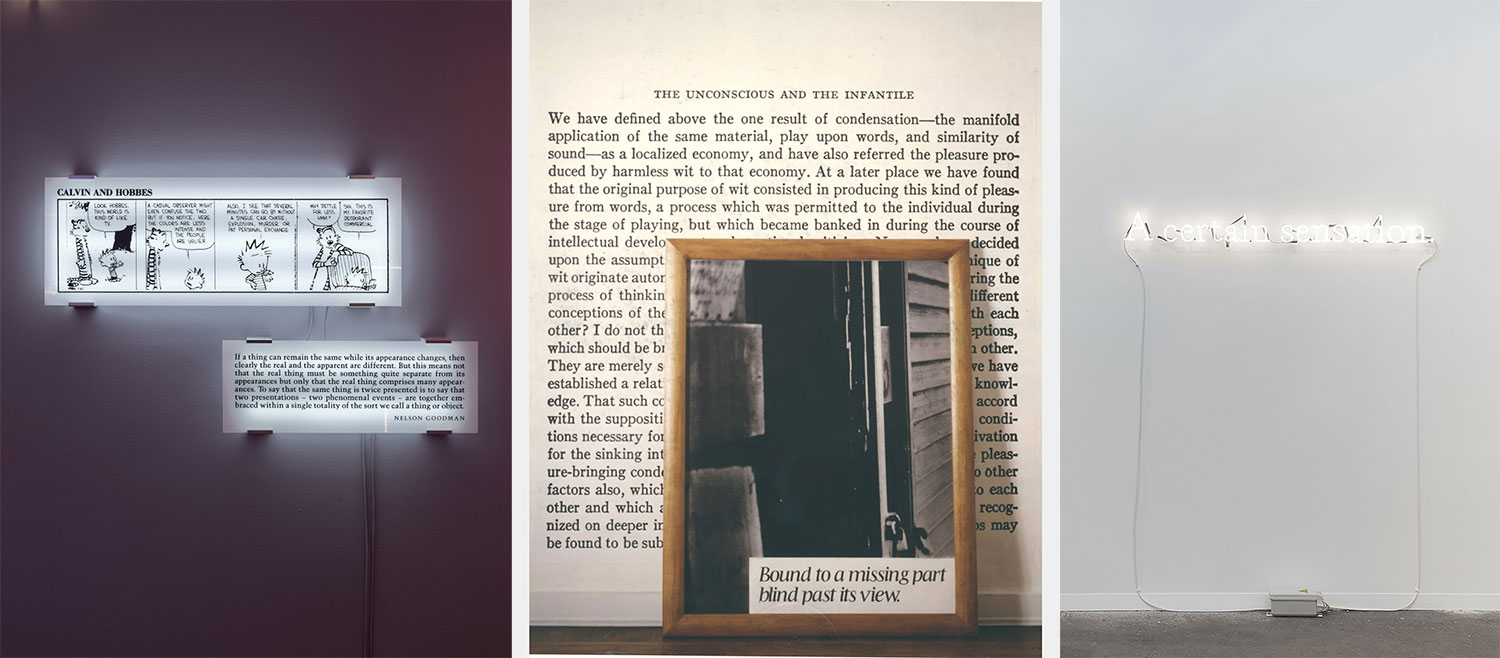

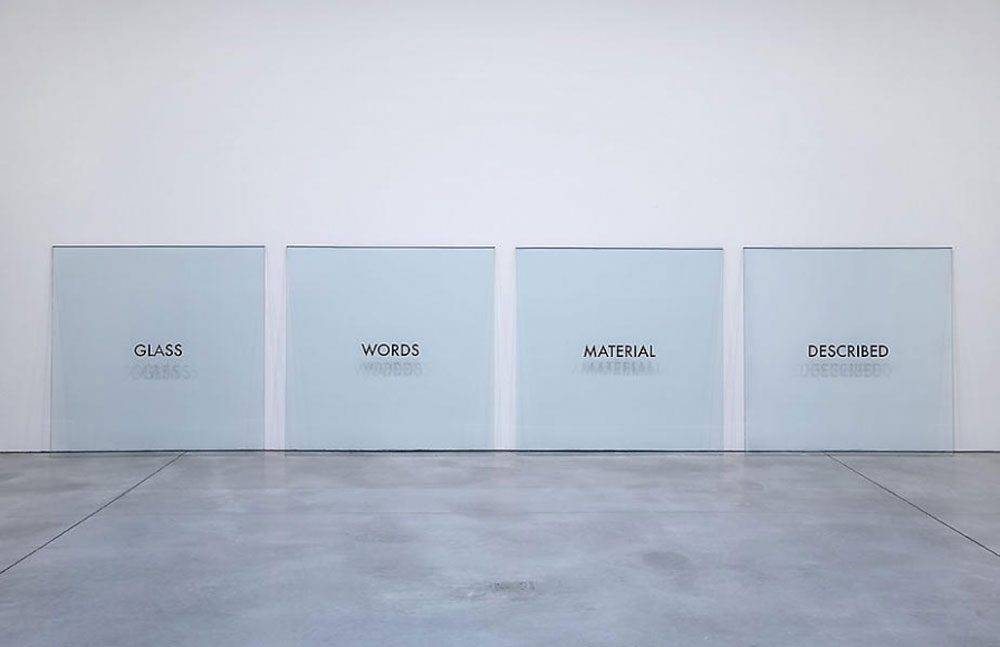

Joseph Kosuth believed that images and any traces of artistic skill and craft should be eliminated from art so that ideas could be conveyed as directly, immediately, and purely as possible. There should be no obstacles to conveying ideas, and so images should be eliminated since he considered them obstacles. This notion became one of the major forces that made Conceptual Art a Movement in the late-1960s. “The art I call Conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art. Thus, it is . . . a working out, a thinking out, of all the implications of all aspects of the concept ‘art. Born in 1945 in Toledo, Ohio, Kosuth attended the Toledo Museum School of Design from 1955 to 1962 and studied privately under the Belgian painter Line Bloom Draper. From 1963 to 1964, he was enrolled at the Cleveland Art Institute. In 1965 Kosuth moved to New York to attend the School of Visual Arts, he would later join the faculty. He soon abandoned painting and began making Conceptual works, which were first shown in 1967 at the exhibition space he co-founded, known as the Museum of Normal Art. In 1965 he created his first conceptual work, “One and Three Chairs”, which displayed an actual chair, its photograph, and a text with the definition of the word chair. This work was a milestone in the development of Western art, and it started a trend that favoured the idea or the concept of a work over a physical object. He continued his “One and Three” series of installations and created his “First Investigations”, which were subtitled “Art as Idea as Idea”. The title for the series was inspired by Ad Reinhardt’s comment in 1958 that “art is art as art and everything else is everything else”. Kosuth’s reductive presentation of words has been compared to Reinhardt’s reductive, geometric abstract painting. Reinhardt submitted a copy of Julia R. de Forest’s “Short History of Art” to Kosuth’s 1967 exhibition “Fifteen People Submit Their Favorite Book”. In 1967, he established the New York City exhibition space Museum of Normal Art. In 1969 Kosuth held his first solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York and in the same year became the American editor of the journal “Art and Language”, that was based in the United Kingdom. Kosuth had served at the periodical until 1979 when its contributors had dissidences on the content. Later, he fulfilled the similar duties at the art magazine “The Fox” (1975-76) and “Marxist Perspectives” (1977-78). In 1969, he published his seminal “Art after Philosophy” a three-part essay published in “Studio International”, in which he explained how Marcel Duchamp was crucial for altering the direction of modernist art from radical visual developments to radical ideas and meanings expressed with ordinary, non-artistic materials and asserted that visual art could be adapted for investigations of meaning in language. In the late-1960s, he also started to make installations with words applied to various objects or surfaces, shaped with neon light tubes. These words usually created short, simple statements that were quite straightforward and self-evident. From 1971-72 he studied anthropology and philosophy at the New School for Social Research, New York. The philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, among others, influenced the development of his art from the late ‘60s to mid ‘70s. By the 1970s, as people were saving his “Photostats” (quick photographic copies of text” as souvenirs and thus “objectifying” and “fetishizing” them, Kosuth published these artworks as advertisements in magazines to further undermine their object-like value. Kosuth’s work has consistently explored the production and role of language and meaning within art. His nearly forty year inquiry into the relation of language to art has taken the form of installations, museum exhibitions, public commissions and publications throughout Europe, the Americas and Asia, including Documenta V, VI, VII and IX (1972, 1978, 1982, 1992) and the Biennale di Venezia in 1976, 1993 and 1999. Since the beginning of the 1990s, Joseph Kosuth has also worked on large installations commissioned by many public institutions in various countries, which include Government-sponsored monument to the Egyptologist Jean Francois Champollion, “Words of a Spell, for Noëma” for the city of Tachikawa (1994), the Deutsche Bundesbank (1997), the Parliament House in Stockholm (1998), the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (1999), the renovated Bundestag building in Berlin (2001), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (2003), the Louvre in Paris (2009), the work on the façade of the Council of State of the Netherlands (2011) and the National Library of France in Paris (2012). He exhibited “Il Linguaggio dell’Equilibrio / The Language of Equilibrium” at the Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order on the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, Venice. This was presented concurrently with the 2007 Biennale di Venezia and “Neither Appearance nor Illusion” (2009–10) at the Louvre in Paris.

Joseph Kosuth believed that images and any traces of artistic skill and craft should be eliminated from art so that ideas could be conveyed as directly, immediately, and purely as possible. There should be no obstacles to conveying ideas, and so images should be eliminated since he considered them obstacles. This notion became one of the major forces that made Conceptual Art a Movement in the late-1960s. “The art I call Conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art. Thus, it is . . . a working out, a thinking out, of all the implications of all aspects of the concept ‘art. Born in 1945 in Toledo, Ohio, Kosuth attended the Toledo Museum School of Design from 1955 to 1962 and studied privately under the Belgian painter Line Bloom Draper. From 1963 to 1964, he was enrolled at the Cleveland Art Institute. In 1965 Kosuth moved to New York to attend the School of Visual Arts, he would later join the faculty. He soon abandoned painting and began making Conceptual works, which were first shown in 1967 at the exhibition space he co-founded, known as the Museum of Normal Art. In 1965 he created his first conceptual work, “One and Three Chairs”, which displayed an actual chair, its photograph, and a text with the definition of the word chair. This work was a milestone in the development of Western art, and it started a trend that favoured the idea or the concept of a work over a physical object. He continued his “One and Three” series of installations and created his “First Investigations”, which were subtitled “Art as Idea as Idea”. The title for the series was inspired by Ad Reinhardt’s comment in 1958 that “art is art as art and everything else is everything else”. Kosuth’s reductive presentation of words has been compared to Reinhardt’s reductive, geometric abstract painting. Reinhardt submitted a copy of Julia R. de Forest’s “Short History of Art” to Kosuth’s 1967 exhibition “Fifteen People Submit Their Favorite Book”. In 1967, he established the New York City exhibition space Museum of Normal Art. In 1969 Kosuth held his first solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York and in the same year became the American editor of the journal “Art and Language”, that was based in the United Kingdom. Kosuth had served at the periodical until 1979 when its contributors had dissidences on the content. Later, he fulfilled the similar duties at the art magazine “The Fox” (1975-76) and “Marxist Perspectives” (1977-78). In 1969, he published his seminal “Art after Philosophy” a three-part essay published in “Studio International”, in which he explained how Marcel Duchamp was crucial for altering the direction of modernist art from radical visual developments to radical ideas and meanings expressed with ordinary, non-artistic materials and asserted that visual art could be adapted for investigations of meaning in language. In the late-1960s, he also started to make installations with words applied to various objects or surfaces, shaped with neon light tubes. These words usually created short, simple statements that were quite straightforward and self-evident. From 1971-72 he studied anthropology and philosophy at the New School for Social Research, New York. The philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, among others, influenced the development of his art from the late ‘60s to mid ‘70s. By the 1970s, as people were saving his “Photostats” (quick photographic copies of text” as souvenirs and thus “objectifying” and “fetishizing” them, Kosuth published these artworks as advertisements in magazines to further undermine their object-like value. Kosuth’s work has consistently explored the production and role of language and meaning within art. His nearly forty year inquiry into the relation of language to art has taken the form of installations, museum exhibitions, public commissions and publications throughout Europe, the Americas and Asia, including Documenta V, VI, VII and IX (1972, 1978, 1982, 1992) and the Biennale di Venezia in 1976, 1993 and 1999. Since the beginning of the 1990s, Joseph Kosuth has also worked on large installations commissioned by many public institutions in various countries, which include Government-sponsored monument to the Egyptologist Jean Francois Champollion, “Words of a Spell, for Noëma” for the city of Tachikawa (1994), the Deutsche Bundesbank (1997), the Parliament House in Stockholm (1998), the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region (1999), the renovated Bundestag building in Berlin (2001), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (2003), the Louvre in Paris (2009), the work on the façade of the Council of State of the Netherlands (2011) and the National Library of France in Paris (2012). He exhibited “Il Linguaggio dell’Equilibrio / The Language of Equilibrium” at the Monastic Headquarters of the Mekhitarian Order on the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, Venice. This was presented concurrently with the 2007 Biennale di Venezia and “Neither Appearance nor Illusion” (2009–10) at the Louvre in Paris.