TRACES:Luciano Fabro

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Italian Sculptor, Conceptual Artist and Writer Luciano Fabro (20/11/1936-22/6/2007). His work expands the expressive possibilities of sculpture in the second half of the 20th century. His art associates the use of simple and common materials that redefine the nature of the object and its space with a constant poetic reflection on the practice of sculpture, evident in the numerous texts in which the artist has always related thought with experimentation in new practices. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind the Italian Sculptor, Conceptual Artist and Writer Luciano Fabro (20/11/1936-22/6/2007). His work expands the expressive possibilities of sculpture in the second half of the 20th century. His art associates the use of simple and common materials that redefine the nature of the object and its space with a constant poetic reflection on the practice of sculpture, evident in the numerous texts in which the artist has always related thought with experimentation in new practices. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

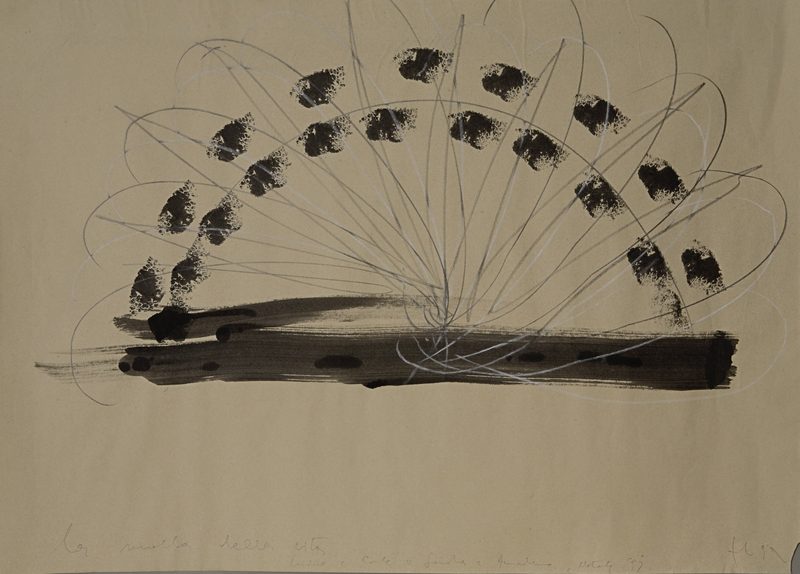

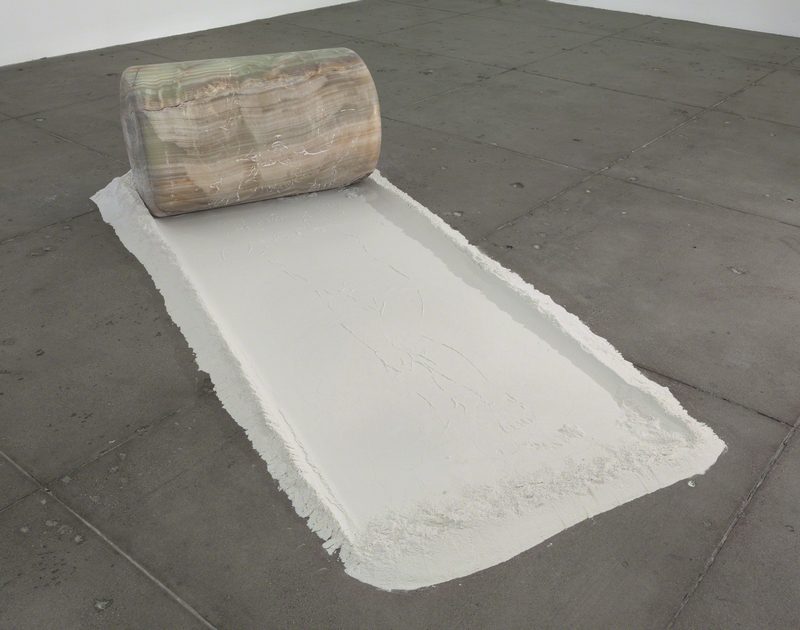

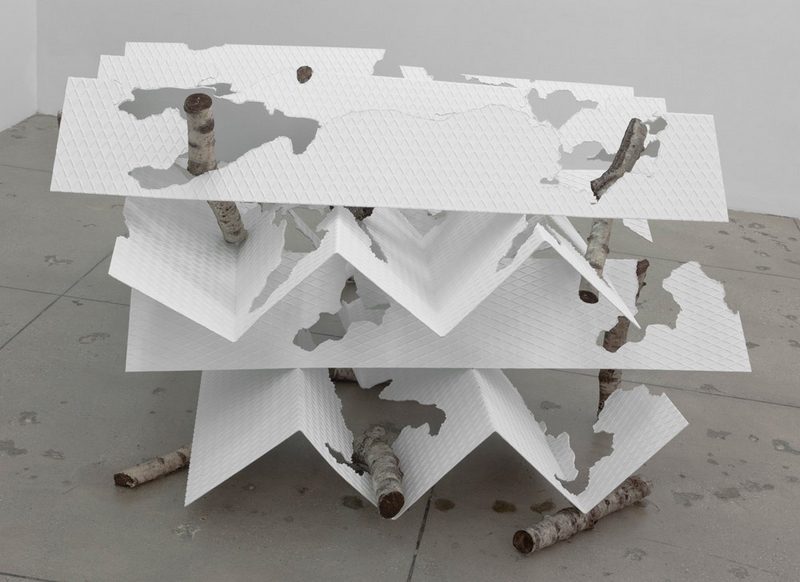

Luciano Fabro, is best known for a series of sculptures in which the outline of the Italian peninsula was metamorphosed into an array of expressive, often disturbing shapes. The materials used were unconventional: thin, curling shreds of paper, a tight roll of copper strips, a twisted sheet of iron wire. It is no accident that he began these works in the late 1960s, at a time of exceptional political and social upheaval, but they exemplify the audacity that marked his whole career. Fabro was born in Turin, but spent his most formative years in Treppo Grande, near Udine, where, he quickly developed a fascination for avant-garde art. This led him in 1958 to visit the Venice Biennale: the experience of Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases, which dramatically introduced the element of space into otherwise flat surfaces, was succeeded by direct contact with Piero Manzoni, whom Fabro met when he moved to Milan in the following year. Above all, he was impressed by Manzoni’s attempts to encourage real interaction between the object and its public. One of Fabro’s first works in 1963 was had the title “Tubo da mettere tra i fiori”. It was a site-specific installation designed for a Milanese garden, even if it was never displayed there, it was made of telescopic steel tubes. He made several works that deals with steel tubes in dialogue with basic physical laws of nature. Four years later, in 1967, Fabro created an installation totally covered with mirrors on the inside and outside walls. The unsettling sensation that this produced was enhanced by interior microphones broadcasting the visitor’s reaction to the rest of the gallery. Fabro’s interest in exploring modes of perception was shared with other young artists, he took part in the exhibition “Arte Povera -IM Spazio” (27/9-20/10/67) at the galleria La Bertesca, in Genoa. This was the first exhibition to apply the name Arte Povera to this type of work. The exhibition was divided into two sections : “Arte Povera”, with contributions by Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali and Emilio Prini, and “IM Spazio”, featuring works Umberto Bignardi, Mario Ceroli, Paolo Icaro, Renato Mambor, Eliseo Mattiacci and Cesare Tacchi. An entertaining but idiosyncratic character, Fabro fiercely protected his independence, even unsuccessfully trying in 1971 to have the movement’s exhibition retitled as simply a list of names. Despite this ambivalent attitude, he was unquestionably one of the most important exponents of Arte Povera, often working with appropriately humble, mundane materials, as well as with more traditional media. In 1972 the pleats and creases of women’s skirts, photographed in minute detail, briefly became one of his most obsessive subjects, while in the same year he also completed a series of grotesque clawed feet, placed at the end of immense tree-like legs, sheathed in shantung silk. This fantastic, mythical quality only intensified in later decades. Like many contemporaries, Fabro increasingly drew on Italy’s ancient heritage, interpreted with an almost baroque energy and flair. This tendency culminated in “The Sun” (1997), in which seven hollow segments of a column, arranged horizontally on the Tate gallery’s floor, created a series of ray-like shapes around, in Fabro’s words, “A nucleus of geometric emptiness”. Fabro frequently made references to other 20th-century artists, ranging from Marcel Duchamp to Piet Mondrian and Lucio Fontana. Evidently he felt as much nostalgia for the heroic days of Modernism as for the age of Pericles. By the end of his career he was aware that he himself had passed from the shock of the new to the comfort of the familiar. One of his most successful later works, “Sisyphus” (1994), required the museum visitor to roll an engraved marble cylinder over a layer of flour, leaving an impression of the Corinthian king condemned to push a boulder for all eternity. He died on 22 June 2007 in Milan by a heart attack.

Luciano Fabro, is best known for a series of sculptures in which the outline of the Italian peninsula was metamorphosed into an array of expressive, often disturbing shapes. The materials used were unconventional: thin, curling shreds of paper, a tight roll of copper strips, a twisted sheet of iron wire. It is no accident that he began these works in the late 1960s, at a time of exceptional political and social upheaval, but they exemplify the audacity that marked his whole career. Fabro was born in Turin, but spent his most formative years in Treppo Grande, near Udine, where, he quickly developed a fascination for avant-garde art. This led him in 1958 to visit the Venice Biennale: the experience of Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases, which dramatically introduced the element of space into otherwise flat surfaces, was succeeded by direct contact with Piero Manzoni, whom Fabro met when he moved to Milan in the following year. Above all, he was impressed by Manzoni’s attempts to encourage real interaction between the object and its public. One of Fabro’s first works in 1963 was had the title “Tubo da mettere tra i fiori”. It was a site-specific installation designed for a Milanese garden, even if it was never displayed there, it was made of telescopic steel tubes. He made several works that deals with steel tubes in dialogue with basic physical laws of nature. Four years later, in 1967, Fabro created an installation totally covered with mirrors on the inside and outside walls. The unsettling sensation that this produced was enhanced by interior microphones broadcasting the visitor’s reaction to the rest of the gallery. Fabro’s interest in exploring modes of perception was shared with other young artists, he took part in the exhibition “Arte Povera -IM Spazio” (27/9-20/10/67) at the galleria La Bertesca, in Genoa. This was the first exhibition to apply the name Arte Povera to this type of work. The exhibition was divided into two sections : “Arte Povera”, with contributions by Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali and Emilio Prini, and “IM Spazio”, featuring works Umberto Bignardi, Mario Ceroli, Paolo Icaro, Renato Mambor, Eliseo Mattiacci and Cesare Tacchi. An entertaining but idiosyncratic character, Fabro fiercely protected his independence, even unsuccessfully trying in 1971 to have the movement’s exhibition retitled as simply a list of names. Despite this ambivalent attitude, he was unquestionably one of the most important exponents of Arte Povera, often working with appropriately humble, mundane materials, as well as with more traditional media. In 1972 the pleats and creases of women’s skirts, photographed in minute detail, briefly became one of his most obsessive subjects, while in the same year he also completed a series of grotesque clawed feet, placed at the end of immense tree-like legs, sheathed in shantung silk. This fantastic, mythical quality only intensified in later decades. Like many contemporaries, Fabro increasingly drew on Italy’s ancient heritage, interpreted with an almost baroque energy and flair. This tendency culminated in “The Sun” (1997), in which seven hollow segments of a column, arranged horizontally on the Tate gallery’s floor, created a series of ray-like shapes around, in Fabro’s words, “A nucleus of geometric emptiness”. Fabro frequently made references to other 20th-century artists, ranging from Marcel Duchamp to Piet Mondrian and Lucio Fontana. Evidently he felt as much nostalgia for the heroic days of Modernism as for the age of Pericles. By the end of his career he was aware that he himself had passed from the shock of the new to the comfort of the familiar. One of his most successful later works, “Sisyphus” (1994), required the museum visitor to roll an engraved marble cylinder over a layer of flour, leaving an impression of the Corinthian king condemned to push a boulder for all eternity. He died on 22 June 2007 in Milan by a heart attack.