PRESENTATION: Sophie Taeuber Arp-Living Abstraction, Part II

The Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp was a pioneer of abstraction. With an air of playful ease, her interdisciplinary creations dismantled longstanding barriers between art and life. Fusing the experimentalism of the avant-garde circles in which she moved in Zurich and Paris with her technical training and experience as a teacher of applied art, she devised a form of abstraction brought to life by expert craftsmanship. At the time of her death in a tragic accident in 1943, her oeuvre encompassed textile pieces, bead works, a puppet theater, costumes, murals, furniture, architecture, graphic designs, paintings, drawings, sculptures, and reliefs (Part II).

The Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp was a pioneer of abstraction. With an air of playful ease, her interdisciplinary creations dismantled longstanding barriers between art and life. Fusing the experimentalism of the avant-garde circles in which she moved in Zurich and Paris with her technical training and experience as a teacher of applied art, she devised a form of abstraction brought to life by expert craftsmanship. At the time of her death in a tragic accident in 1943, her oeuvre encompassed textile pieces, bead works, a puppet theater, costumes, murals, furniture, architecture, graphic designs, paintings, drawings, sculptures, and reliefs (Part II).

By Dimitris Lempesis

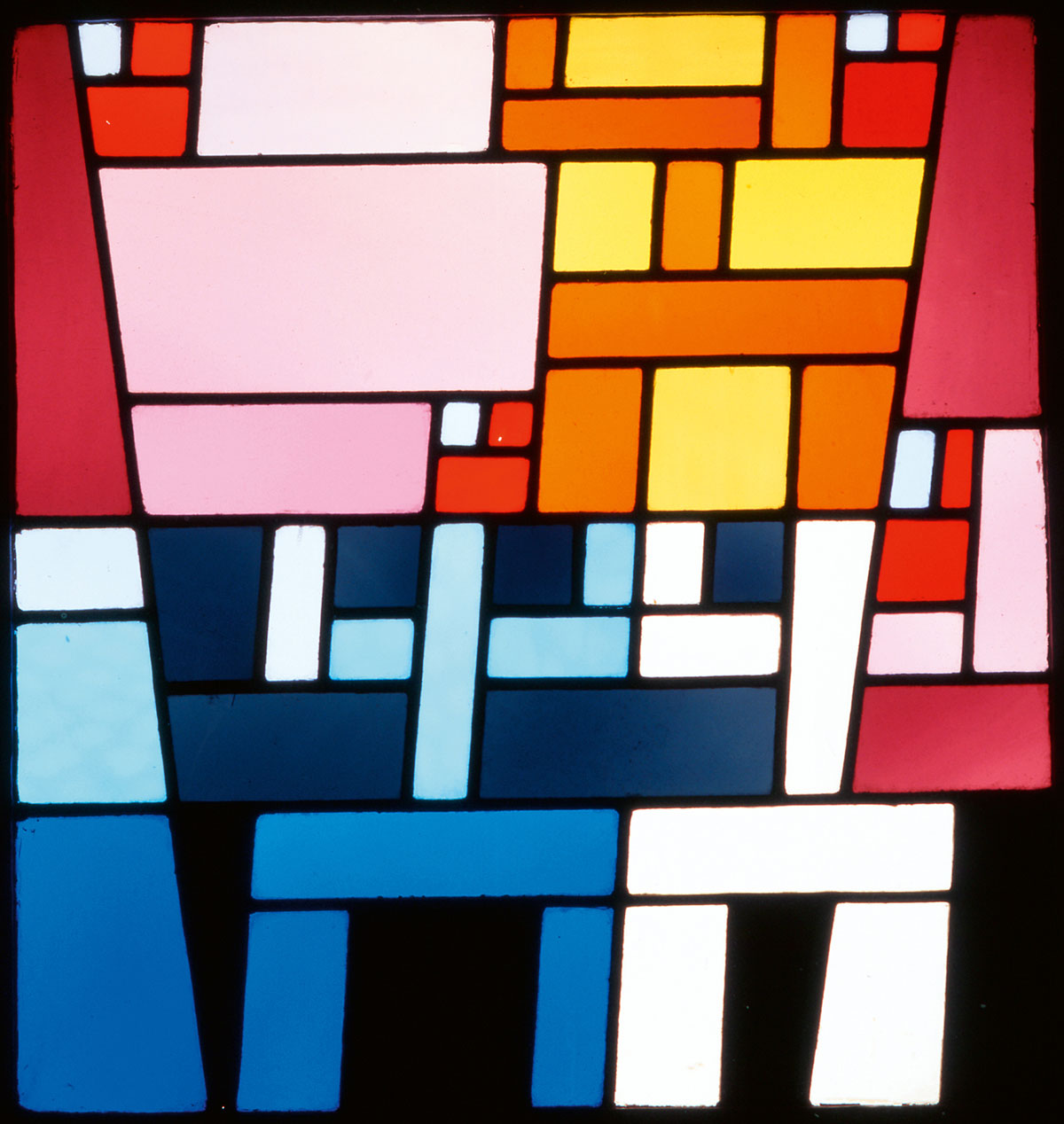

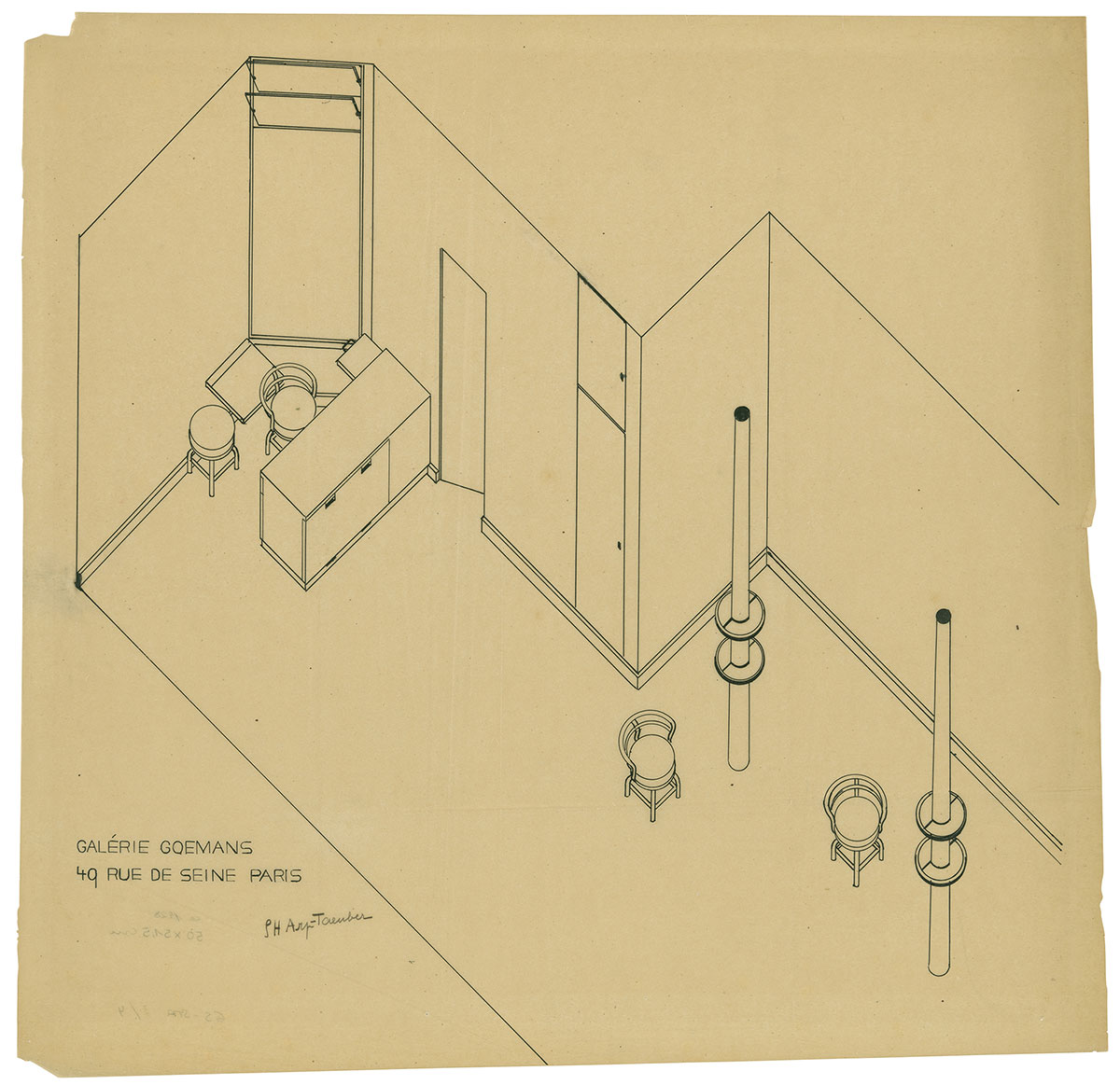

Photo: MoMA Archive

Bringing Together Some 300 Works including textiles, beadwork, polychrome marionettes, architectural and interior designs, stained glass windows, works on paper, paintings, and relief sculptures, the exhibition “Living Abstraction” highlights Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s Distinctive Cross-Pollinating Approach to Abstraction, this is the first major US exhibition in 40 years to survey this multifaceted abstract artist’s innovative and wide-ranging body of work. The exhibition is organized chronologically, beginning with works produced soon after the artist’s move to Zurich in 1914, and ending with those created during World War II, in the months immediately preceding her untimely death in 1943. Sophie Taeuber was born in Davos on 19/1/1889 and grew up near St. Gallen following the death of her father. With her mother and three siblings she spent her childhood and youth in Trogen, surrounded by nature as well as architecture of historical significance. From her eldest brother, a seafarer, she gained impressions of different cultures such as those of indigenous North American peoples while still a child. The twentieth century is still young when Sophie Taeuber-Arp decides to study applied arts. It is a time when the prevalence of industrial mass production prompts a newfound appreciation for manual craftsmanship and the beauty of simple materials. She enrolls at the progressive Deb-schitz School in Munich, where students of both sexes learn together. Its teachers believe that applied and fine arts — the creative design of objects and art created for its own sake — are closely allied. Decorative floral patterns are in fashion. The motifs with which Taeuber-Arp adorns necklaces, beaded bags, and pillowcases, how- ever, are increasingly abstract. Colorful drawings and gouaches (a wa-ter medium) help her develop her ideas. She presents only the finished craftwork to the public, not these design sketches. In a contemporary perspective, they appear as works of — in some instances, radical — abstract art in their own right. In 1914, Sophie Taeuber-Arp settles in Zurich. During the First World War, the city in neutral Switzerland becomes a sanctuary for many members of Europe’s artistic avant-gardes. Taeuber-Arp studies modern expressive dance with Rudolf von Laban. Hans Arp, whom she will later marry, introduces her to members of the anti-bourgeois Dada movement, and she translates a sound poem by Hugo Ball into dance. Thanks to her training in applied art, Taeuber-Arp is a skilled woodwork-er. She designs turned vessels and a series of abstract heads, and has her photograph taken with the so-called Dada Head. In 1918, the Swiss Marionette Theater in Zurich puts on the play King Stag, for which she creates an entire ensemble of wooden puppets with movable limbs. Unfortunately, due to the Spanish Flu pandemic, the production sees no more than three performances. In 1916, Zurich’s Trade School hires Sophie Taeuber-Arp to teach design and embroidery. For the next twelve years, the steady income from this position will sustain her and Hans Arp, whom she marries in 1922, through a period of economic difficulty. She presents her textile works in exhibitions, including those held by the Swiss Werkbund and the Basel-based artists’ association Das Neue Leben (The New Life), which seeks to undo the division between applied and fine art. Her pillows, tablecloths, and rugs feature geometric shapes as well as abstract renderings of animal and human figures. To test the effect of her motifs, Taeuber-Arp works with painted scraps of paper, which she shifts around and assembles in varying combinations. In the second half of the 1920s, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and her husband become French citizens. She regularly spends time in Strasbourg, where she receives a series of commissions to design interiors. A recurring motif in her works from this period is the figure with bent arms. It appears in the designs for Hotel Hannong, the murals at the Heimendinger residence, and the stained-glass windows for the pharmacist André Horn’s apartment. Photographs she takes on her travels with Hans Arp and artist friends like Kurt Schwitters and Sonia Delaunay-Terk in the 1920s and 1930s attest to her interest in distinctive shapes: in the arcades of Roman architecture, rock formations, and the sea of beach chairs on the German island of Rügen, life in all its variety provides her with inspiration. The revolutionary visual language of geometric abstraction encounters the fulness of life in Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s biggest project in Strasbourg: her designs for the Aubette, an amusement center in the heart of the city, are based on compositions of square and rectangular fields of color. She herself takes on the tearoom, the Aubette bar, and the bar in the lobby, bringing in Hans Arp and Theo van Doesburg, the cofounder of the Dutch artists’ association De Stijl, for other components of the project. Critics later extol the Aubette as the “Sistine Chapel of modernism”. The building’s contemporary users, however, never warm to the innovative materials and clean lines. Major alterations in the 1930s destroy this Gesamtkunstwerk, and only a partial reconstruction can be experienced today. The Aubette commission enables Sophie Taeuber-Arp and her husband to buy a piece of land on the outskirts of Paris, and she draws up plans for a modern studio built of local limestone. Moving to France for good, she resigns from her teaching post at the Zurich Trade School. Taeuber-Arp’s designs for interior decorations and furnishings emphasize their functionality with bold colors and clean forms, reflecting a desire for the modernization of all domains of life that unites creative minds all over Europe. The art critic Michel Seuphor introduces her to his circle of friends, including members of the Paris avant-garde, and she joins the association Cercle et Carré. In 1930, she exhibits her first abstract paintings. When the group Cercle et Carré disbands, Sophie Taeuber-Arp becomes a member of its successor organization, the association Abstraction- Création. Her abstract compositions are shown in exhibitions in France and abroad. Taeuber-Arp’s style is a variant of Constructivism, whose very name suggests an architectonic treatment of abstract forms. Her preference for bold colors is unchanged. The rhythmic arrangement of elements in her work conveys an impression of inward motion—perhaps a vivid reminiscence of the bodily experiences of dance and choreography from her Zurich years? As a coeditor, managing director, correspondent, and layout de-signer of the trilingual magazine Plastique/Plastic, Taeuber-Arp seeks to foster the exchange of ideas between avant-gardes on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1937, Sophie Taeuber-Arp has twenty-four works in the group exhibition “Konstruktivisten” at Kunsthalle Basel. Although it is arguably the single most important presentation of her art in her lifetime, only one extant installation photograph includes a glimpse of her work: a segment of “Animated Circle Picture” can be seen between contributions by Naum Gabo, El Lissitzky, and László Moholy-Nagy. Georg Schmidt, who will later lead the Kunstmuseum Basel, de-scribes the abstraction on display in the exhibition as a universal medium: an unequivocal, truthful, and serene visual language, he writes, it represents a vigorous affirmation of life and optimism amid the contemporary political upheavals. As Basel demonstrates its openness to the avant-garde with exhibitions and dedicated collectors, the same art faces sharp hostility from the National Socialists in neighboring Germany. When Nazi troops invade France and occupy Paris in 1940, the Arps seek refuge in the south of France. After stops in Nérac and Veyrier, they are taken in by friends in Grasse. The dramatic change in their circumstances, the series of relocations, the food shortages and difficulty of obtaining art supplies not only negatively affect Taeuber-Arp’s health, they also leave an imprint on her work: tangled lines exuding a sense of restlessness now become the hallmark of her drawings. A temporary visa for Switzerland allows the Arps to escape the occupation of southern France. On a cold January night in 1943, Sophie Taeuber-Arp dies of carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a stove at her artist friend Max Bill’s house in Zurich.

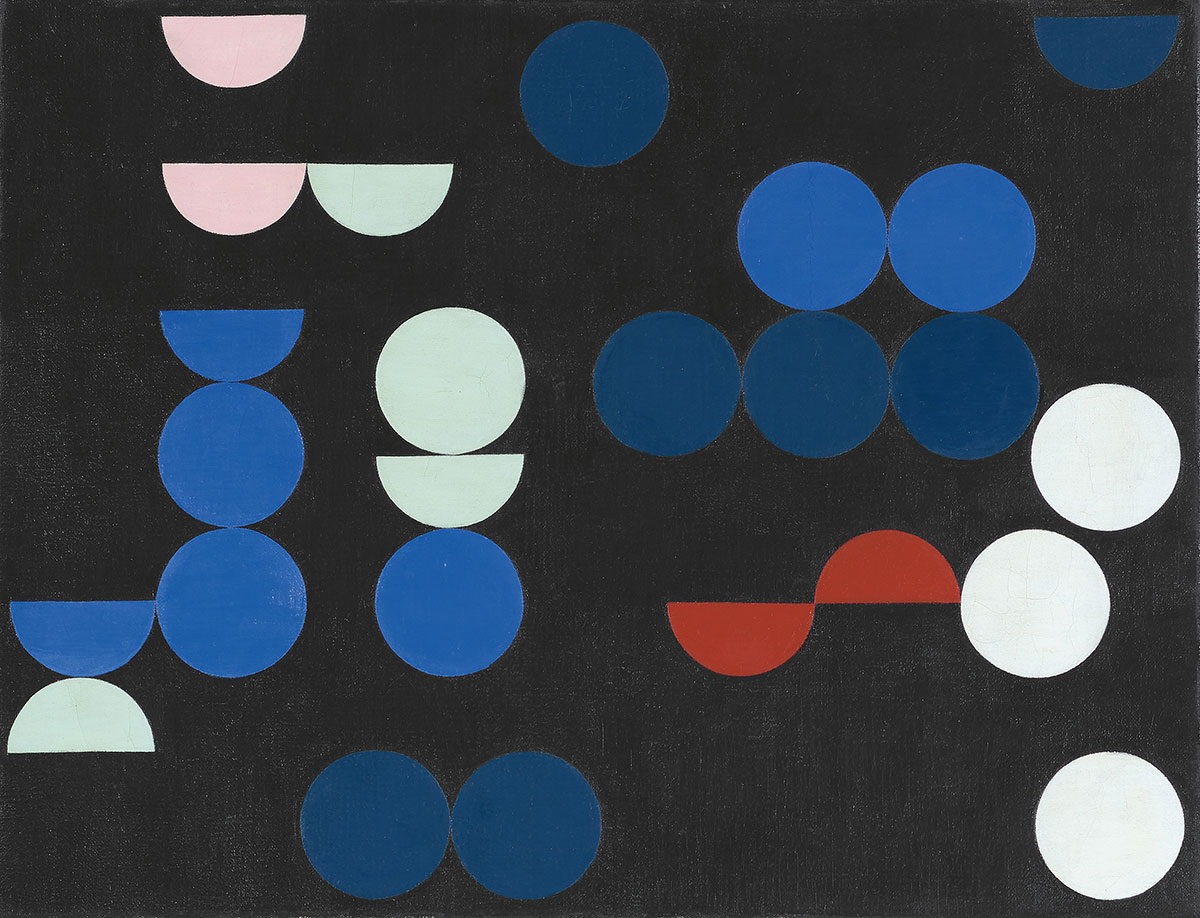

Photo: Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Animated Circle Picture. 1935. Oil on canvas. 19 7/8 × 25 5/8″ (50.5 × 65.1 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, N.Y. Charles Clifton Fund. Courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery, photo Brenda Bieger

Info: Curators Anne Umland, Walburga Krupp, Eva Reifert, and Natalia Sidlina, Assistant curator: Laura Braverman, MoMA (Museum of Modern Art), 11 West 53 Street, Manhattan, NY, USA, Duration: 21/11/2021-12/3/2022, Days & Hours: Mon-Fri & Sun 10:30-17:30, Sa 10:30-19:00, www.moma.org

Right: Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Composition (Two Disks Cut by a Line). 1931. Oil and metallic paint on canvas. 12 5/8 × 10 1/16″ (32 × 25.5 cm). Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Switzerland. Gift of the Müller-Widmann Collection, Basel. Courtesy Aargauer Kunsthaus Aarau, photo Brigitt Lattmann

Right: Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Gradation. 1934. Oil on canvas. 25 9/16 × 19 11/16″ (65 × 50 cm), Private collection, © Luis Lourenço

Right: Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Lines of Summer. 1941 Colored pencil and pencil on paper. 25 9/16 × 19 11/16″ (65 × 50 cm). Private collection, on long-term loan to the Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Switzerland. Courtesy Aargauer Kunsthaus Aarau, photo Peter Schälchli