PRESENTATION: Guido Casaretto-Of Goats, Scapes and Appropriations

Guido Casaretto reconstructs objects and processes through selection and new combinations, thus creating a hyperreality that ultimately conceals the original. It is not about the distinction between subject and depiction, reality and imagination, but rather about knowledge of a continuum between becoming and elapsing, about dynamic systems whose development over time is unpredictable.

Guido Casaretto reconstructs objects and processes through selection and new combinations, thus creating a hyperreality that ultimately conceals the original. It is not about the distinction between subject and depiction, reality and imagination, but rather about knowledge of a continuum between becoming and elapsing, about dynamic systems whose development over time is unpredictable.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Zilberman Gallery Archive

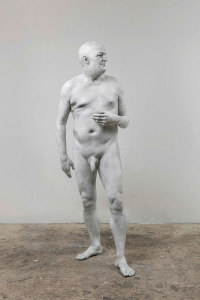

The first encounter with Guido Casaretto’s works, which are trying to understand the human’s most natural ways of perceiving our surroundings and of reproducing these processes, is a transference experience of a visual sensation to a haptic one. With each work witnessing the many processes and steps of its production, Casaretto’s meticulous crafting builds up the physicality and tactility of producing them, especially apparent in the exaggerated dimensions of some. Guido Casaretto’s experimentation with materials, such as concrete, skin, soil, and epoxy, is the spine for his body of works: the materials not only determine the outcome by a deliberate imitation of their nature, they are also heavy with the historical, art historical and technological connotations. For him, it is about imitating these processes in order to enable himself and the viewer to understand something that has come into being over time. His solo exhibition “Of Goats, Scapes and Appropriations” comprises sculptural works and the video “Crossing Carnevale” (2019) in which the artist deals with different appropriation processes and allows them to become a setting for confrontation themselves. In this, Casaretto conducts various appropriation activities in the way they occur in the course of an individual life, but can also be constitutive for social processes. For “Black Hole: Church Bench” (2020), Casaretto has created six casts of a pew he had already found. He starts by moulding the bench before shredding the latter and creating, out of the shredded wood, mixed with resin, as many reproductions as the material will allow. The colorfulness of the sculptures is determined by the material while the reproduction process is reminiscent of industrial production. At the same time, there remains an identity with the original through the material in that the congregation’s contact with it, during their ritual acts, has become inscribed. In the same way that a historical utensil is decontextualized in an archaeological museum and becomes an artefact, Casaretto’s benches are torn out of their functional context and imbued with new meaning. The reproductions, too, establish a relationship with something with its own time and place. The original pew is from Saint Stephen’s Catholic Church in Istanbul’s Yeşilköy neighbourhood. It is a church that Casaretto’s family used to attend in a neighbourhood that was known for its mixed population of Greek, Italian, Armenian or, as Casaretto often points out, Levantine origin. He describes himself as a Levantine whose Italian family – most of them merchants – had immigrated at a time when the Ottoman Empire still existed. Casaretto describes the Mediterranean region as a recurring reference in his works. A larger-then-life figurative sculpture depicts the British comedian, actor and author Stephen Fry who has been dubbed by critics as the last “Renaissance man” of the 21st century on account of his versatile erudition and talent. In an ironic comment on this, Casaretto shapes Fry in the style of a Mannerist sculpture. It is a different process to his busts where he uses traditional techniques to analogically back-translate figures from computer animations. Learned knowledge is handed down in the handcraft that Casaretto imitates then masters through repetition until automated movement sequences have been achieved. In this way, Casaretto shapes orecchiette, a particular form of Italian pasta from Apulia and traditionally made by hand, from clay. The remains of the production process, the crumbs and misshapes, remain visible. Here, Casaretto is subjecting his artistic process to external guidelines, subverting the supposedly sovereign authorship of the artist. For his video “Crossing Carnevale” (2019), Casaretto turns to a pre-Christian Mamuthones carnival tradition in Sardinia that is still staged today and which Casaretto transfers to an alien landscape, the dried-up salt lake, Lake Tuz in Central Anatolia. Legend has it that the Mamuthones set out from Sardinia and crossed the sea to Liguria in order to kidnap and sacrifice a member of another tribe in the sense of a scapegoat mechanism, something that can also be observed in other carnival traditions. Casaretto shows the return journey across the sea with the hostage. In this case, the sea is the dried-up salt lake that the four people are crossing, an empty landscape that gives the impression of being on another planet. In the video, the second person is the hostage while Casaretto plays the role of a warrior. The video has no sound and the movements are in slow motion; at times, we get a panoramic bird’s-eye view of the group then also in detail closer up. The warriors are wearing ancient costumes, bells and animal masks with horns that have been recreated from other materials, in part from resin. In addition, Casaretto has sculpted a mountain in a relief from a wall of piled-up porous concrete. A built wall is a man-made boundary between inside and outside, between the other and oneself, just as a mountain constitutes a natural border. At the same time, Casaretto adopts trompe l’oeil practices. It is less a boundary and more the illusion of a mountain view that is created.

Photo: Guido Casaretto, Black Hole (church bench), Cast of wood chips, 6 pieces; 90 x 130 x 50 cm (each), 2020, © Guido Casaretto, Courtesy the artist and Zilberman Gallery

Info: Zilberman Gallery, Goethestraße 82, Berlin, Germany, Duration: 11/12/2021-12/2/2022, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-18:00, www.zilbermangallery.com