PHOTO:Robert Mapplethorpe-Intérieur Jour

Robert Mapplethorpe became famous, not to say, notorious, in the 1970s and 1980s for his photographs of the male nude and sexually explicit, gay imagery. Although often considered controversial, Mapplethorpe tested the right to individual freedom of expression. These images were not meant to be titillating or obscene but beautiful in a traditionally classical way. His work, therefore, holds a significant place in the history of artistic struggle to depict the world as it is, with honesty and truth.

Robert Mapplethorpe became famous, not to say, notorious, in the 1970s and 1980s for his photographs of the male nude and sexually explicit, gay imagery. Although often considered controversial, Mapplethorpe tested the right to individual freedom of expression. These images were not meant to be titillating or obscene but beautiful in a traditionally classical way. His work, therefore, holds a significant place in the history of artistic struggle to depict the world as it is, with honesty and truth.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery Archive

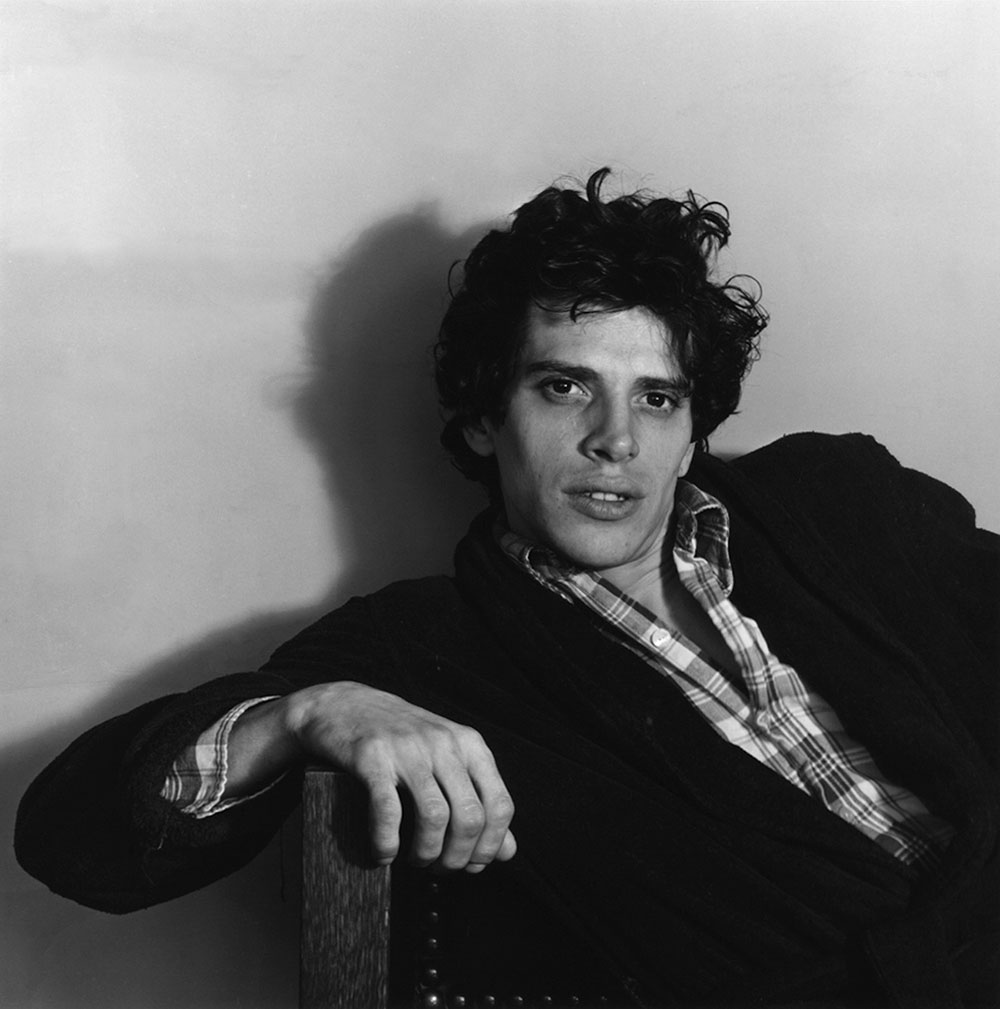

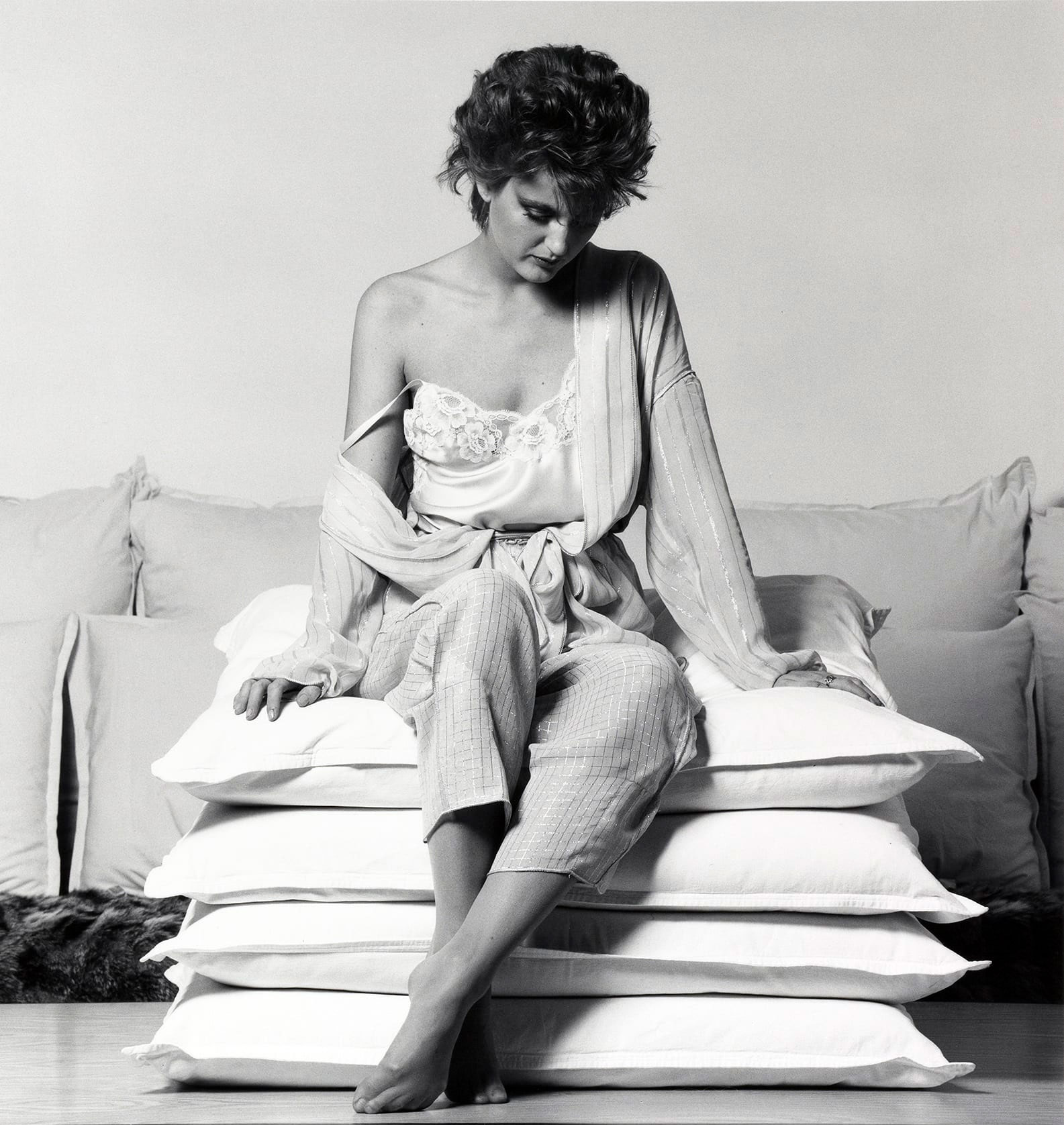

Through a selection of works that explore a more intimate facet of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography, the exhibition “Intérieur Jour” emphasises a delicate and discreet approach to the photographic model. Placed on two shelves that occupy the entire length of the second floor of Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, a set of portraits in various formats makes up a display that recalls a domestic setting, like a family album of familiar faces. The choice is not related to the identity of the people but rather to the community they constitute, which, through its diversity, draws a portrait of the artist. Some belong to a socio-cultural elite, others are part of the New York underground and then there are the children of both. All of them are characterised by a relaxed attitude and by a particular play of light, which underline their humanity. Rather than the sculptural beauty of the athletic bodies that have so often been emphasised, the aim here is to let the determination of a look, the fragility of a moment and reverie speak for themselves. Guided by his own practice, which is nourished by photography, Jean-Marc Bustamante reflects on the de-hierarchisation of the image that thwarts what we already know about Mapplethorpe, his search for perfection and his obsession with ‘the beautiful image’. Photographs of empty space, with light passing through them, accompany this gallery of portraits like counter-fields that introduce an absence, a screen. These views of interiors in which nothing is revealed except the architecture of the space itself, are indeed, through the diffusion of light, invitations to develop one’s own eye as a spectator. Photographed in their intimate domestic space, the portraits of adults reveal a vulnerability far removed from the dramatic tension of studio portraits. Sitting on her sofa, Stella Astor (1976) looks defiantly into the lens, while the portrait of Francesca Thyssen (1981) catches her in a moment of abandon. Mapplethorpe believed that he had to have the consent of the people he photographed and once said that children were the most difficult subject to photograph: “You can’t control them. They never do what you want them to do”. These were mostly children of friends like Sarabelle Miller – the daughter of gallery owner Robert Miller, or the niece of Milton Moore that was one of his favorite models. These images capture their innocence but also their confidence and their sense of playfulness.

Robert Mapplethorpe was raised in Queens, a middle child in a Catholic family from which he was later somewhat estranged. He attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn from 1963 to 1970, taking courses in painting, drawing, and sculpture, with no intention at that time of becoming a photographer. During the 1960s he and poet/musician Patti Smith became close friends, living together for several years, part of that time at the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan. Mapplethorpe produced collages, and his jewelry designs had attracted a potential financial backer, but he chose not to continue in that direction. During this period he had also developed an interest in experimental film. Mapplethorpe had discovered the shops and bookstores on 42nd Street as a teenage art student, and they had a profound effect on his work. His initial interest in photography was, in part, an outgrowth of the collages he had been constructing with images from pornographic magazines. With his first camera, a Polaroid SX-70 provided by the late curator of prints and photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, John McKendry, Mapplethorpe was able to produce photographic images of his own. Later he would acquire a 4-by-5-inch view camera, and finally a Hasselblad. Throughout his career, Mapplethorpe used a variety of photographic processes, including photogravure, Polaroid, platinum prints on paper and linen, cibachrome, and dye transfer. He did not have a strong interest in darkroom processes, so he worked closely with his technician to obtain the look he wanted in his work. Mapplethorpe produced photographs for liquor advertisements as well as for fashion and interior design publications, and he was known for his portraits of entertainment and art world celebrities. During the 1970s he was the staff photographer for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, and his photographs appeared in journals such as Vogue and Esquire. His last commissioned portrait was of U.S. Surgeon General C.Everett Koop for Time magazine, taken less than two months before the artist’s death.

Photo: Robert Mapplethorpe, Francesca Thyssen, 1981, Silver gelatin print, 50.8 × 40.6 cm. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

Info: Curator: Jean-Marc Bustamante, Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, 7 Rue Debelleyme, Paris, France, Duration: 4/9-16/10/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, https://ropac.net