ART CITIES:Berlin-Sim Chi Yin

Sim Chi Yin is a photographer and artist from Singapore, currently based in London and Beijing. Her practice integrates multiple mediums including photography, film, sound, text and archival material and performative readings. Combining rigorous research with intimate storytelling, Sim’s works often explore issues relating to history, memory, conflict and migration, and their consequences.

Sim Chi Yin is a photographer and artist from Singapore, currently based in London and Beijing. Her practice integrates multiple mediums including photography, film, sound, text and archival material and performative readings. Combining rigorous research with intimate storytelling, Sim’s works often explore issues relating to history, memory, conflict and migration, and their consequences.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Zilberman Gallery Archive

Sim Chi Yin’s exhibition “One Day We’ll Understand” questions the colonial and postcolonial histories and historiographies of the 12-year guerrilla war in British Malaya (an area today covered by Malaysia and Singapore), which the British colonial power euphemistically termed the “Malayan Emergency” (1948–1960). Communists, who had led the resistance against Japan in World War II, now spearheaded the anti-colonial struggle. It was one of the early hot conflicts in the global Cold War, using tactics such as population-control strategies and the defoliant chemical Agent Orange years before the Vietnam War. British authorities tried to break the resistance through detentions, deportations, and the resettlement of civilians from the edges of the jungle to so-called “New Villages” to starve the communist insurgents of supplies of food, medicine and men. The exhibition is rooted in Sim’s family history, namely the history of her paternal grandfather, a journalist and left-wing intellectual. Like over 30,000 other leftists and sympathisers, he was imprisoned by the British and deported to China, where he was later executed by the ruling Kuomintang government. Starting with this personal story, Sim expands her research into an historical and artistic examination of the official and colonial historiographies of the war and its combatants. Two revolutionary songs (The Internationale & Goodbye Malaya), the former conveying an aspirational mind set, the latter loss – are included in Sim Chi Yin’s video installation “Requiem”. We hear the voices of former deportees and exiles, some of whom are still not allowed to return to Malaysia. The sound of their fragile voices, sometimes forgetting the lyrics, permeates the exhibition “One Day We’ll Understand”. These ethereal voices suffused with a sense of loss echo as we take in the atmospheric landscape photographs the artist has made of sites of memory of this war around present day Malaysia and southern Thailand. In one scene at dusk, an elephant emerges out of the jungle thicket, a split-second encounter that transforms into an apparition. A table with empty chairs intrigues us into thinking a surrepticious meeting has just been summarily disbanded – or suggests the absence of the former anti-colonial fighters or people displaced and killed in acts that have still not been accounted for today, while British and Commonwealth soldiers are commemorated at heroes’ cemeteries.

Sim Chi Yin’s exhibition “One Day We’ll Understand” questions the colonial and postcolonial histories and historiographies of the 12-year guerrilla war in British Malaya (an area today covered by Malaysia and Singapore), which the British colonial power euphemistically termed the “Malayan Emergency” (1948–1960). Communists, who had led the resistance against Japan in World War II, now spearheaded the anti-colonial struggle. It was one of the early hot conflicts in the global Cold War, using tactics such as population-control strategies and the defoliant chemical Agent Orange years before the Vietnam War. British authorities tried to break the resistance through detentions, deportations, and the resettlement of civilians from the edges of the jungle to so-called “New Villages” to starve the communist insurgents of supplies of food, medicine and men. The exhibition is rooted in Sim’s family history, namely the history of her paternal grandfather, a journalist and left-wing intellectual. Like over 30,000 other leftists and sympathisers, he was imprisoned by the British and deported to China, where he was later executed by the ruling Kuomintang government. Starting with this personal story, Sim expands her research into an historical and artistic examination of the official and colonial historiographies of the war and its combatants. Two revolutionary songs (The Internationale & Goodbye Malaya), the former conveying an aspirational mind set, the latter loss – are included in Sim Chi Yin’s video installation “Requiem”. We hear the voices of former deportees and exiles, some of whom are still not allowed to return to Malaysia. The sound of their fragile voices, sometimes forgetting the lyrics, permeates the exhibition “One Day We’ll Understand”. These ethereal voices suffused with a sense of loss echo as we take in the atmospheric landscape photographs the artist has made of sites of memory of this war around present day Malaysia and southern Thailand. In one scene at dusk, an elephant emerges out of the jungle thicket, a split-second encounter that transforms into an apparition. A table with empty chairs intrigues us into thinking a surrepticious meeting has just been summarily disbanded – or suggests the absence of the former anti-colonial fighters or people displaced and killed in acts that have still not been accounted for today, while British and Commonwealth soldiers are commemorated at heroes’ cemeteries.

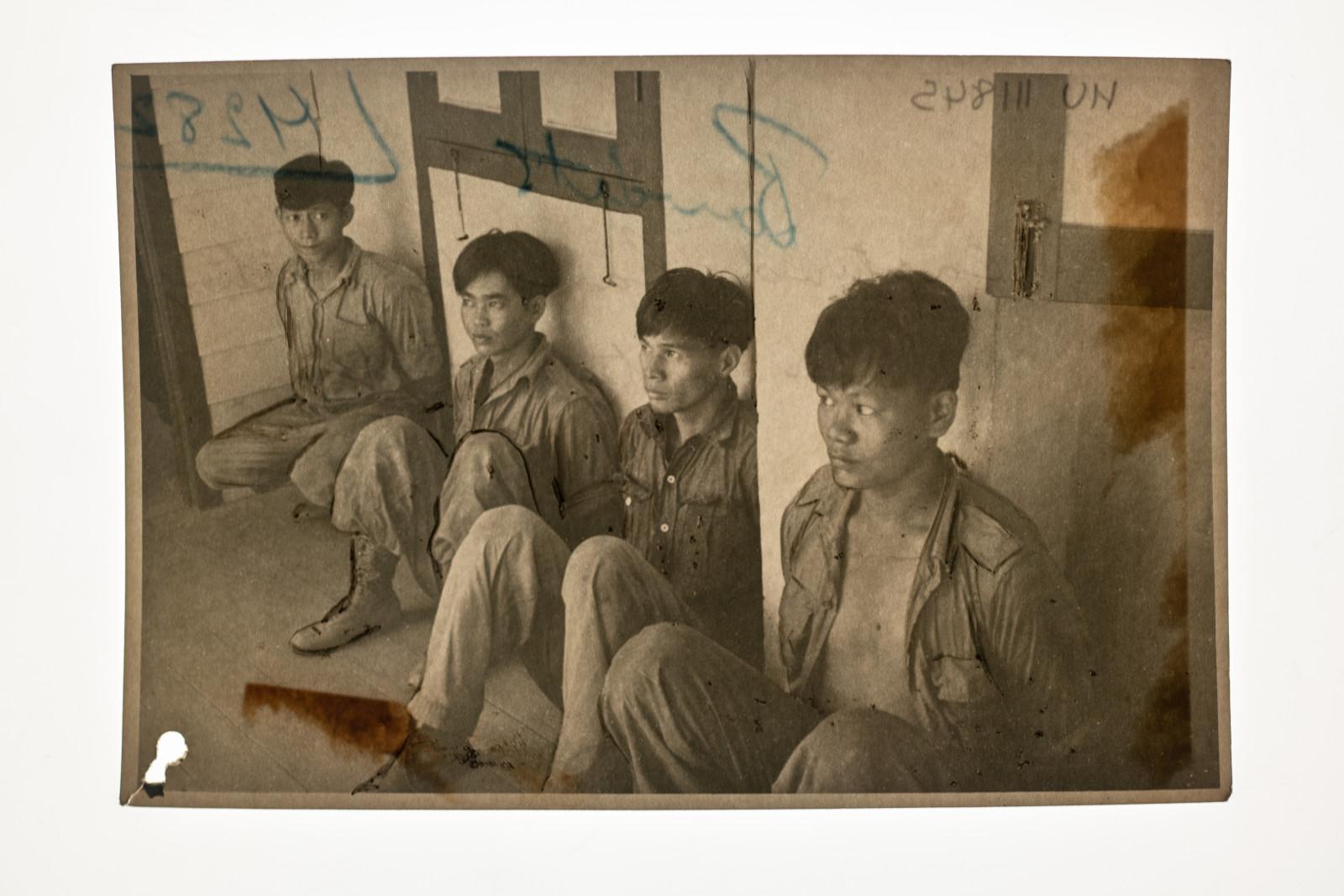

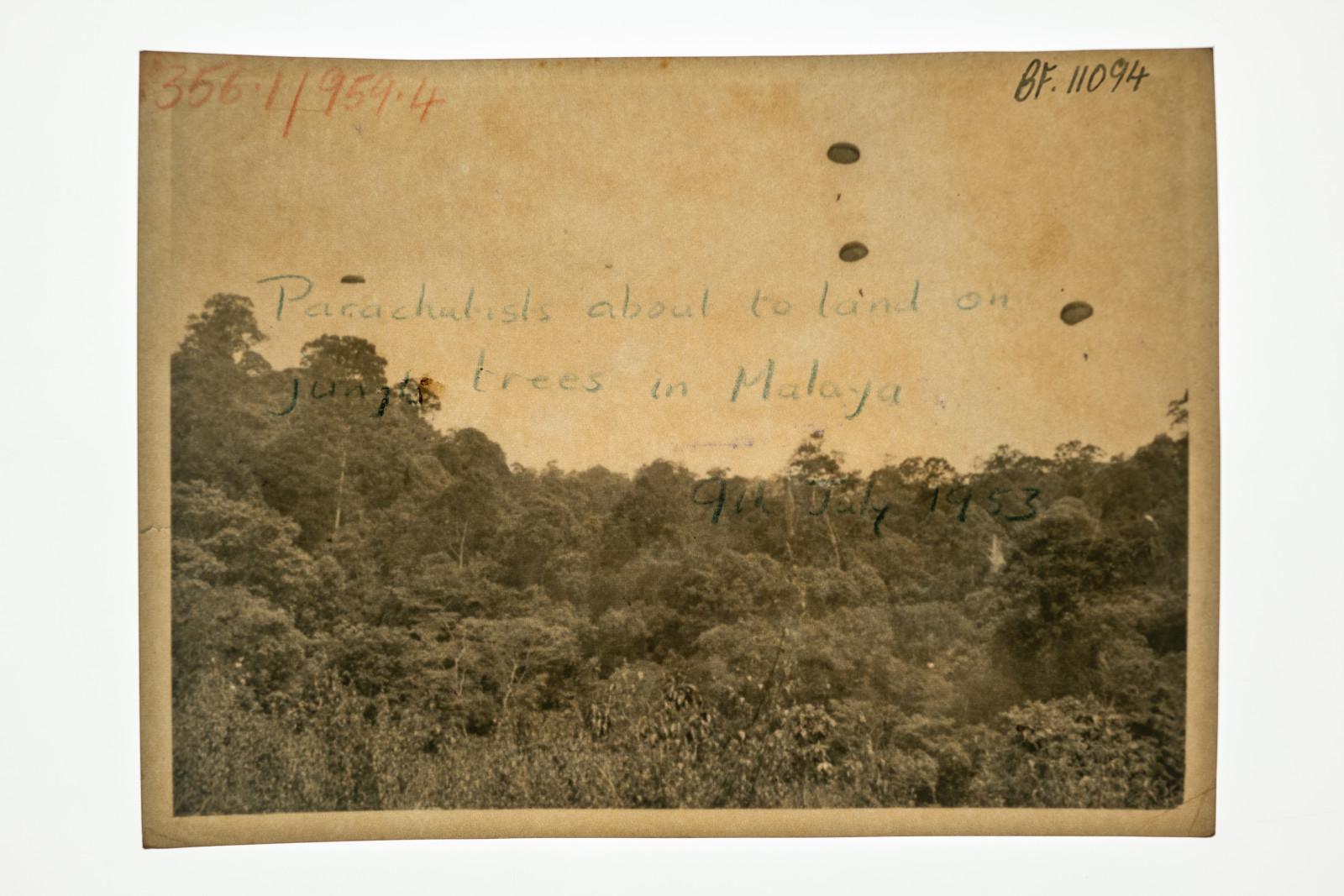

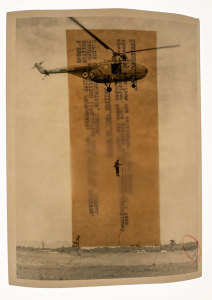

In her most recent series “Interventions” Sim excavates photos from the colonial archive at the Imperial War Museum in London that were used by British authorities for media campaigns and psychological warfare to legitimise national military operations against anti-colonial fighters. Sim has photographed these prints on a light table so that the markings and labelling, which would otherwise be concealed on the back, can be seen through the image like a palimpsest. The transparency of the foil prints on glass plates enables viewing from two sides, with either the text or the image appearing back-to-front. Who has the power to define? Sim questions the indexicality of material evidence by exposing the mechanisms of colonial interpretation. One photo shows a helicopter dropping a British solider down a length of rope into the jungle; another shows a rubber plantation with white cloth strips tacked to their trunks, a signal to workers not to put themselves at the service of British rubber exporters. In another picture, freshly-captured guerrilla fighters can be seen squatting on the floor of a police station, the “Bandits” label, which is how the insurgents were criminalised, visible through the folio. The figures are outlined with a black pencil in places, for the purpose of publication in the press. Today, these people are still taboo in Malaysia and Singapore, echoing the way the British defamed them as bandits or communist terrorists, archiving them on propaganda pictures, wanted lists, or lists of deportees or exiles. But paradoxically it was that very contact with the colonial power that preserved them in history, creating an uneasy dynamic where the vanquished are only remembered through the victors’ eyes, something Sim deconstructs in her work. The polyphony from historical letters from both sides of the conflict, as well as from oral history accounts by leftist combatants and witnesses, offer an insight into Sim Chi Yin’s research. The accounts, collected from Sim’s interviews with 35 deportees and exiles in four countries, form a ‘counter-archive’ to the histories and historiographies in the official archives. Sim asked her subjects about their experiences of displacement and deportation, and how things turned out for them later. Photographs of objects, such as a mine detector and a prosthetic leg, which the survivors showed the artist as memorabilia or evidence during the interviews, form part of her counter-archive. They are material witnesses to history.

Photo: Sim Chi Yin, Remnants #4, Perak, Malaysia, 2017, © Sim Chi Yin, Courtesy of the artist and Zilberman Gallery

Info: Zilberman Gallery, Goethestraße 82, Berlin, Germany, Duration: 14/9-27/11/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-18:00, www.zilbermangallery.com