PHOTO:Sally Mann

Sally Mann first achieved recognition for her work towards the end of the 1980s when photographs she had taken of her family, especially of her three children, began to attract attention. She created several series full of intimacy and sensuality featuring moving images of a childhood very much attached to nature, like the artist experienced her in own childhood. Later, she turned her attention to pure landscape photography, producing equally extensive series.

Sally Mann first achieved recognition for her work towards the end of the 1980s when photographs she had taken of her family, especially of her three children, began to attract attention. She created several series full of intimacy and sensuality featuring moving images of a childhood very much attached to nature, like the artist experienced her in own childhood. Later, she turned her attention to pure landscape photography, producing equally extensive series.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Galerie Karsten Greve Archive

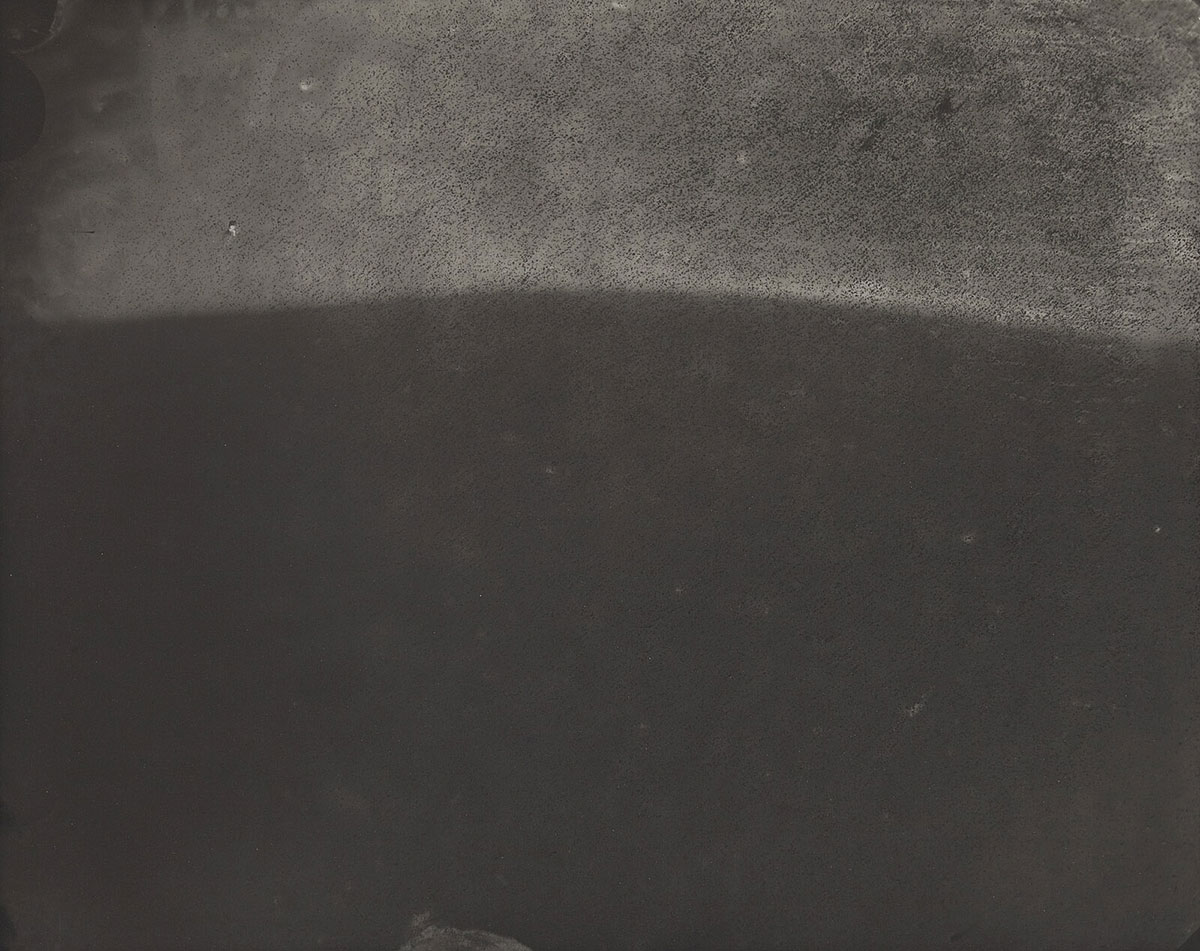

These images reveal the artist’s deep love for her native land, the American South, a sparsely populated, rural area with lush vegetation. It is the atmospheric impact that makes her images so outstanding. They radiate a lyric and nostalgic mood, expressing a strong sense of the beauty and the history of this land. Time seems to stand still in Sally Mann’s landscapes. This impression is enhanced by her obvious attention to craftsmanship. She uses a hundred-year-old large-format camera and prefers early, complex techniques, a sort of tribute to the pioneers of landscape photography. Distortions, overexposures or scratching created intentionally in the dark room emphasize the dreamlike atmosphere in her photographs. Following the success of her large retrospective “Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings” at Jeu de Paume in 2019, her solo exhibition is an opportunity to rediscover two iconic series by the artist: Deep South and Battlefields through a selection of thirty large-format prints produced at the turn of the 2000s. At a young age, Sally Mann started taking pictures in and around Lexington, Virginia, where she was born and still lives. She roamed the vast American outdoor spaces from the late 1970s, with nature a predominant presence in her snapshots. In 1996, she discovered the states neighbouring Virginia and travelled further into the Deep South. Initially envisaged as an exploration of those enthralling landscapes, her trips transformed into a pursuit of memory and a confrontation with the ghosts of the past. “Since my place and its story were givens, it remained for me to find those metaphors; encoded, half-forgotten clues within the Southern landscape”. This is how Sally Mann approached her research. At first glance, the pictures in the Deep South series appear to be peaceful and luminous landscapes, balancing between dream and reality. They are a contemplation of the lush nature exalting the beauty of the outdoor spaces of the South of the United States; they are also an exhumation of a traumatizing and harrowing past. From dense vegetation in “Deep South #17” to picturesque springs in “Deep South #13”, there is nothing to prepare viewers for the chilling feeling of horror that certain pieces convey. One story in particular etched itself into Sally Mann’s mind at a young age: the violent murder of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African American boy, in 1955. Intended as a “visual pilgrimage”, “Deep South #34 (Emmett Till River Bank)” was taken at the spot where his body was fished out of the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi. Like an uneven scar in the ground, the river is shallow, almost stagnant, surrounded by rocky soil scattered with grass; the grandiose vegetation from the other snapshots in the series is nowhere to be seen. The place that was photographed is the site of a real and identifiable death; the trivialness of the river jars with the gravity of the event.

If at first sight “Deep South” appears to be a refuge, a safe haven, this impression cannot suppress an underlying feeling of violence and death. Battlefields pursues this further. This series takes its place within Sally Mann’s continual research into the history of her homeland and exposes the blood-stained heritage of the Civil War (1861-1865). Through a set of sombre landscapes, the images evoke the grimness of the era of slavery, poverty, injustice, racism and suffering. The pictures are a manifestation of the horror stagnating in the places where the battles of the Civil War took place – Mann calls them “body farms”. Exclusively in shades of dark grey and black, Battlefields retraces the artist’s steps at the various places where she came across vestiges of the bones of lost soldiers, her photography conjuring their memory. Mann took photos as close as possible to the ground, with the sky almost disappearing from her compositions in “Antietam #14” and “Chancellorsville #9”, a point of view mimicking the final moments of fallen soldiers on this land. In “Friedericksburg #22” the trees and the sky become threatening and hostile, with mystical outlines defined by a translucent light. Still, Sally Mann shows that beauty remains present even in death and is treasured by nature, the trees the only witnesses to the dead, serving as their tombs. In order to best record the unique atmosphere of the South, in the 1990s Sally Mann started using an old photographic technique developed in the nineteenth century: wet collodion negative on glass. This process consists of covering a plate of glass with a dense chemical substance named collodion and a silver nitrate-based photosensitive solution. She used a mobile 8×10 darkroom, which she built herself, because the chemical reagents used require instant manipulation in darkness. For Sally Mann, this bygone practice breathed historical feelings into her pieces and gave them a pictorial dimension; it also allowed her to be closer to her pictures, weaving an intimate link between the artist and her medium, while letting her be surprised by the unexpectedness of the results. Sally Mann worked her enlarged prints at times with a tea-based dye and at others with diatomaceous earth and soil from the battlefields, giving the surface a velvet finish. The several-minute-long exposure time and the choice to use old lens, favoured by the artist over new equipment, produced unpredictable imperfections and light fluctuations, pushing certain images to the limits of visibility.

Photo: Sally Mann, Deep South #17, 1998, Gelatin silver enlargement print, toned with tea, Ed. 8/10 + 3 AP, 94,6 x 119,4 cm (37 1/4 x 47 in), Frame: 109,4 x 134 x 2,7 cm, signed, dated and numbered verso, © Sally Mann, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Karsten Greve

Info: Galerie Karsten Greve, 5 rue Debelleyme, Paris, France, Duration: 28/8-30/10/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00, https://galerie-karsten-greve.com