ART-PRESENTATION: Kara Walker-Cut To The Quick

A leading artist of her generation, Kara Walker works in a range of mediums, including prints, drawings, paintings, sculpture, film, and the large-scale silhouette cutouts for which she is perhaps most recognized. Her powerful and provocative images employ contradictions to critique the painful legacies of slavery, sexism, violence, imperialism, and other power structures, including those in the history and hierarchies of art and contemporary culture.

A leading artist of her generation, Kara Walker works in a range of mediums, including prints, drawings, paintings, sculpture, film, and the large-scale silhouette cutouts for which she is perhaps most recognized. Her powerful and provocative images employ contradictions to critique the painful legacies of slavery, sexism, violence, imperialism, and other power structures, including those in the history and hierarchies of art and contemporary culture.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Frist Art Museum Archive

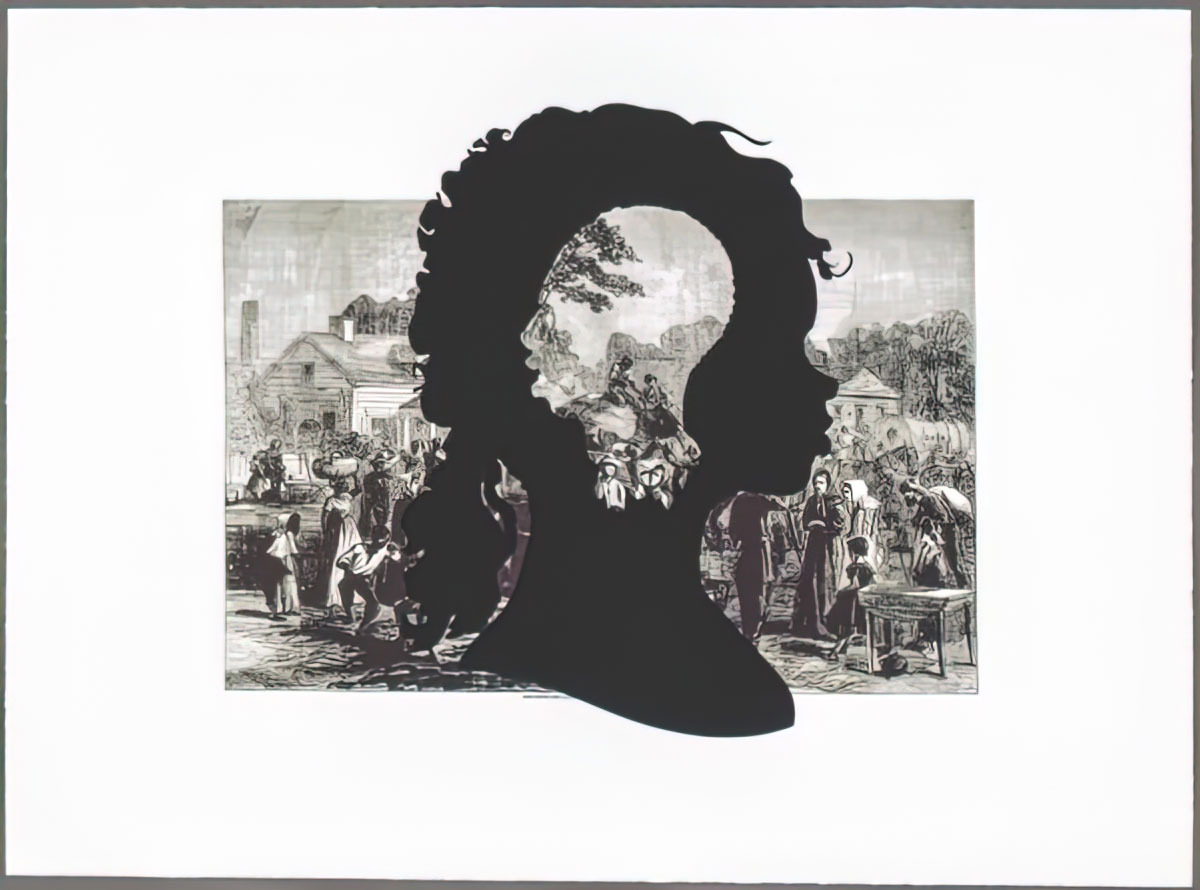

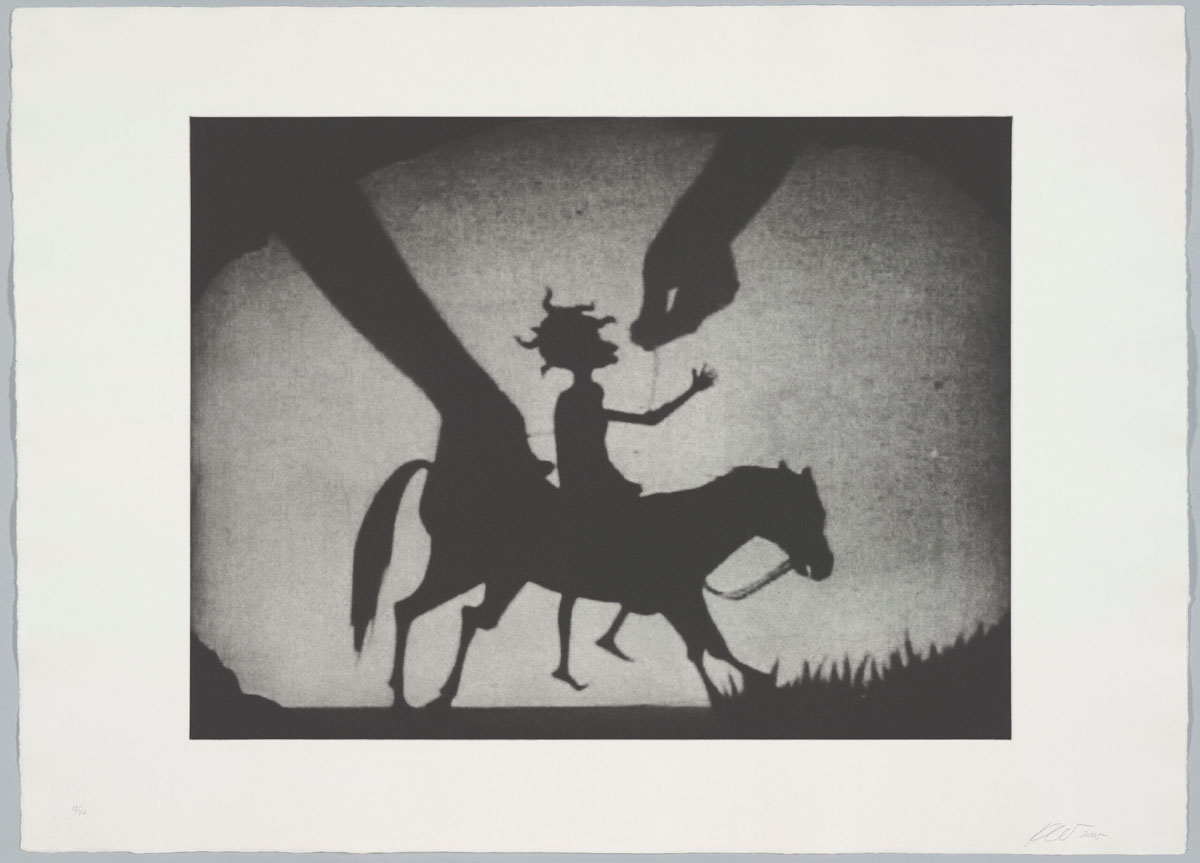

Kara Walker’s exhibition “Cut To The Quick” offers a broad overview of her career through more than 80 works from the collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, premier collectors of works on paper in the United States. Some highlights of the exhibition are the complete “Emancipation Approximation” series and images from the “Porgy & Bess” series. Walker’s process involves extensive research in history, literature, art history, and popular culture. Intentionally unsentimental and ambiguous, the works can be disturbing while also utilizing satire and humor, always exploring the irreconcilable inconsistencies that mirror the human condition. The earliest and latest works in “Cut to the Quick” underscore how negative stereotypes create and reinforce the discrimination and prejudice that limit access to education, employment, property rights, voting rights, social mobility, and a fair share of generational wealth and power. Walker shocked the art world in the 1990s with images of exaggerated physiognomy exhibited in a fine arts context such as the full lips, bug eyes, and wiry hair that define “Topsy” (1994), the character of an enslaved girl in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (1852). The author, intending to be empathetic, ultimately articulated a characterization of otherness based on race that endured after the Civil War, during Jim Crow, segregation, the civil rights era, and beyond. The descendants of formerly enslaved workers continued to receive little of the wealth they created with subsequent farm labor systems such as sharecropping, tenant farming, and the forced servitude practiced in some prisons today. In the next gallery, “Fons Americanus” (2019) condemns the violence and complicity of governments and private enterprise in constructing the transatlantic slave trade and perpetuating its legacies. The bronze replica of Walker’s now-demolished installation in Tate London’s Turbine Hall was based on the Victoria Memorial at Buckingham Palace. Walker’s monument was an allegory of the Black Atlantic and the global waters that disastrously connect Africa to the economic prosperity of America and Europe. The flow of figures and scenes, including an Afro-Caribbean Venus, seafarers, a tree with a hangman’s noose, and the scales of justice, satirize the pride of empire and imperialism. “Porgy and Bess” series: The 1935 opera “Porgy and Bess” is set in 1920s Charleston, South Carolina, to music by George Gershwin with a libretto by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Porgy, a disabled beggar, tries to free the beautiful Bess from her manipulative lover, Crown, and the drug dealer Sportin’ Life. The tragedy was criticized almost from the beginning for its characterization of the lifestyle of poor African Americans, as well as its use of their dialect, as imagined by white authors. While observing rehearsals for a 2011 performance, Walker made sketches “to understand the music and to allow myself to get caught up in the fantasy of theater.” Later, Walker created sixteen original lithographs to illustrate a 2013 publication of the libretto by Arion Press. She also produced four companion lithographs not included in the book. Lithography is well suited to the expressiveness of Walker’s smudges, rubbings, and loose, broad strokes. The artist says of the characters, “They’ve become archetypes of another no less grand drama, that of: ‘American Negroes’ drawn up by white authors, and retooled by individual actors, amid charges of racism, and counter charges of high art on stage and screen, in the face of social and political upheaval, over generations”. “The American Civil War”: Between 1861 and 1865, Harper’s Weekly reported contemporaneous accounts of Civil War battles and political developments, largely in support of Lincoln and the federal government. In 1894, the weekly published one thousand illustrations of battlefields, maps, plans, and likenesses of military figures in Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War, by Alfred H. Guernsey and Henry M. Alden. In 2005, Kara Walker superimposed her signature silhouettes over large-scale prints from the pictorial history. The Harper’s Weekly images had been intentionally inoffensive to a Southern white readership. Walker’s flat, opaque figures insistently interject a previously, conspicuously absent African American point of view. Silhouettes obfuscate the original intention while beckoning the viewer into a black hole of spiraling emotions about the unreliability of history. Who is telling the story? Whose history is included and whose is omitted? Who is validated and who is obliterated?

Photo: Kara Walker, African/American, edition 22/40, 1998. Linocut, 44 x 62 in., Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 1998.53, © Kara Walker

Info: Curators: Susan H. Edwards and Ciona Rouse, Frist Art Museum, 919 Broadway, Nashville, TN, USA, Duration: 23/7-10/10/2021, Days & Hours: Thu-Sat 10:0-17:30, Sun 10:00-17:30, https://fristartmuseum.org

Right: Kara Walker, Boo-hoo (for Parkett no. 59), edition PP 5/6, 2000. Linocut, 40 x 20 1/2 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2003.13. © Kara Walker