PHOTO:Garry Winogrand

Widely considered to be one of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century, Garry Winogrand chronicled the raw visual poetics and contradictions of public life in the United States during the postwar era—on streets and highways, in cities and suburbs, at fairgrounds, national parks, and sporting arenas. As a first-generation Jewish American from a working-class family in the Bronx, New York City, Winogrand developed a subjective approach to photography that questioned narrative uses of the medium and pioneered a “snapshot aesthetic” in contemporary art.

Widely considered to be one of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century, Garry Winogrand chronicled the raw visual poetics and contradictions of public life in the United States during the postwar era—on streets and highways, in cities and suburbs, at fairgrounds, national parks, and sporting arenas. As a first-generation Jewish American from a working-class family in the Bronx, New York City, Winogrand developed a subjective approach to photography that questioned narrative uses of the medium and pioneered a “snapshot aesthetic” in contemporary art.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Fundación MAPFRE Archive

Surveying Garry Winogrand’s career from the early 1950 to his untimely death in 1984, the exhibition hosted by the KBr Fundación MAPFRE photography center in Barcelona, is organized chronologically, from his early magazine work in the 1950s to his street scenes and road trips during the 1960s to media events and rodeos in the 1970s. Upon his untimely death in 1984, after having lived in Texas and California for nearly a decade, Winogrand left thousands of rolls of films undeveloped or unedited. A selection of prints made from these negatives, which curator John Szarkowski helped to develop and proof in advance of the first survey exhibition of Winogrand’s work in 1988, are also on view, giving a fuller picture of the photographer’s expansive and complicated body of work. The exhibition also presents an installation of projections comprising color photographs that have rarely been exhibited. While almost exclusively known for his black-and-white images, Winogrand produced more than 45,000 color slides between the early 1950s and late 1960s. By presenting the color work alongside his more well-known black and white images, this exhibition sheds new light on the career of a pivotal postwar artist and the history of color photography in the United States. After studying at Columbia University (1949-1951), where he met fellow student and photographer George Zimbel, Winogrand became a photojournalist for Pix, Inc., a photo bureau that provided images to news and feature magazines. Starting in 1954, under the mentorship of agent Henrietta Brackman, he started selling commercialphotographs to magazines such as Collier’s, Look, Pageant, and Sports Illustrated. Using a 35 mm camera and a flash, Winogrand often documented athletes in action, musicians or actors performing, and the energy of nightlife in New York City, producing photographs that often illustrated text or were meant to convey a narrative about their subjects. While Winogrand produced much of his work for commercial purposes during the 1950s, these early photographs demonstrate his understanding of the symbolic or poetic power of photography as a descriptive medium. He also made many photographs for his own purposes, both in the city and during his travels. Many of these photographs use the aesthetic of photojournalism, but often resist narrative. This movement against narrative in his own work was perhaps a reaction against the way in which they were often framed in magazines.

In 1960, Winogrand documented the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles. In one of his most iconic images, he photographed John F. Kennedy speaking to an audience of cameramen rather than conventioneers. Seen from behind, Kennedy shares the stage with an electronic double: a small television set broadcasting his speech, presumably for the benefit of backstage journalists. It is only on TV that we see his face—an irony not lost on Winogrand, who would go on to explore the effects of media on American society in the 1960s and 1970s. The photograph also visualizes how television was increasingly displacing magazines and photojournalists by the late 1950s. Around 1960, as his marriage to his first wife, Adrienne Lubow, deteriorated, Winogrand began to photograph women with greater frequency, and the subject remained a particular fixation until 1965, when he met his second wife, Judy Teller. He photographed women both young and old, alone and in groups, walking in the Garment District, sunbathing on the beach, or gathered at events. By presenting women’s changing presence in the street and other public spaces, Winogrand recorded some of the most radical of the decade’s transformations. His images document not only the perceptions and assumptions of one particular male gaze, but also the styles, activities, gestures, and power of women in the era of Second-Wave feminism and the sexual revolution. Winogrand often said that he began to be a serious photographer around 1960. That year he had his first one-person show, and about then he developed his pictorial strategies for photographing street life in New York City, including his use of a wide-angle lens and a tilted picture plane, where the horizon line is askew. He said of this period, “I began to live within the photographic process.” Throughout the 1960s, Winogrand often photographed scenes in midtown Manhattan, particularly along Fifth Avenue. As he stopped working regularly for picture magazines like Collier’s, which closed in 1957, Winogrand increasingly renounced photography’s ability to tell stories and its role in journalism. His pictures of life on the street from this period are often filled with multiple figures and rarely convey a single narrative. They are captivating both for the subjects in their foreground as well as at their edges. Even when bursting with people, his images often express a sense of isolation, suggesting something darker during the tumultuous decade.

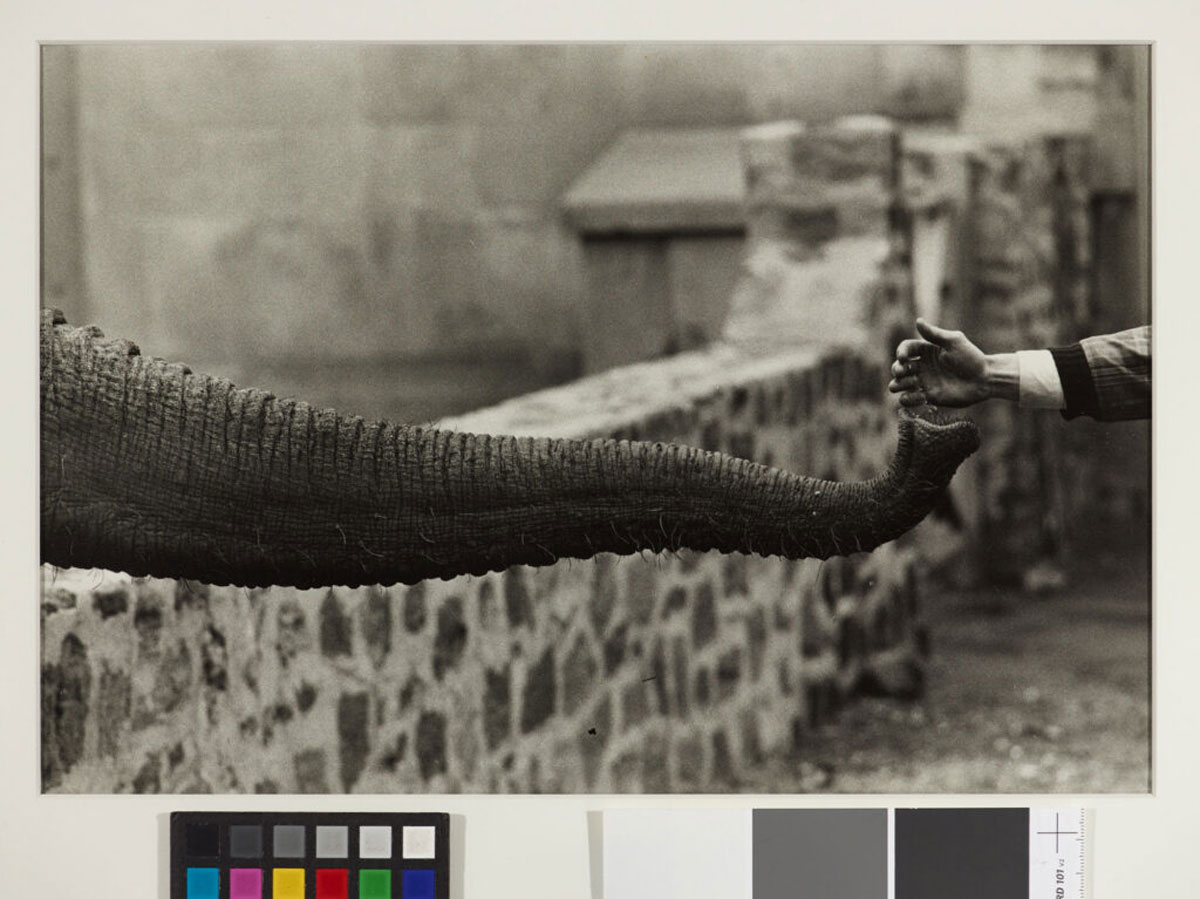

Since Winogrand took the photograph “Central Park Zoo, New York City” (1967) of a white woman and a Black man in New York’s Central Park, each holding a chimpanzee dressed in children’s clothing, many critics have noted the picture’s deliberate ambiguity—not only about the circumstances of how these figures came to be here, but also about the way Winogrand chose to frame them with his camera, cutting out most of the surrounding context. How are viewers to interpret such an image made the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state laws banning interracial marriage violated the U.S. Constitution? During the 1960s, Winogrand became increasingly reluctant to speak about the “meaning” of his photographs, preferring to focus on their form and technique, in spite of their excessive narrative potential. Perhaps this was a reaction against his photojournalistic and advertising work, which was often illustrative. Winogrand would cite Susan Sontag’s influential essay “Against Interpretation” (1964), which deplored the growing impulse at the time to reduce works of art to their content in order to make them mean something. She argued, like Winogrand, in favor of the pleasure and poetry of seeing. In March 1964, Winogrand received his first John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in Photography, to make “photographic studies of American life”. The prestigious grant allowed him to travel across the country that summer, driving through seventeen states in a 1957 Ford Fairlane borrowed from his friend and fellow photographer Lee Friedlander. The photographs are observations of a native New Yorker and a first-generation Jewish American who was dazzled by, yet ambivalent about, the rest of the United States, especially following the assassination of John F. Kennedy and in the midst of the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. Winogrand attempted to visualize what he thought to be a more honest representation of the United States, photographing isolation, consumerism, gender and racial prejudice, and the military-industrial complex. He photographed the effects of airports, malls, suburbia, and observed the peculiar new rituals they inspired. Many of his photographs were made from his car, often framing the picture with its windshield or broad side windows. The body of work “Society of the Spectacle” began in 1969 when Winogrand received his second Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph what he called “the effect of media on events.” Made largely between 1969 and 1973, the project was a notable departure from the seemingly apolitical photographs of pedestrians, partygoers, and zoo animals. Winogrand produced many of the photographs from this series at demonstrations, and many others depict political subjects—including the 1971 presidential candidates’ press conference, New York’s mayor John Lindsay, and the Nixon victory celebration of 1972. In 1977, photographer and friend Tod Papageorge organized an exhibition and book for the Museum of Modern Art titled Public Relations. After the 1960s, Winogrand spent the majority of his life in Texas and California, where he produced several bodies of work. In 1970, after his second marriage to Judy Teller was annulled, Winogrand left New York, taking on various itinerant teaching positions around the country for several years before finally moving to Austin, Texas in 1973 to teach at the University of Texas. There, he completed books “Women Are Beautiful” (1975) and “Public Relations” (1977). He also photographed rodeos, which became the basis of his last book “Stock Photographs: The Forth Worth Fat Stock Show and Rodeo” (1980). In 1978, he received his third Guggenheim Fellowship. That same year he moved to Los Angeles, where he intended to create a photographic study of the state, a place he had visited on numerous trips over the past 30 years. In Texas and California, Winogrand challenged himself to make new types of pictures. Unlike New York, street life in these cities takes place in cars, and many of the pictures Winogrand made there were taken from the front seat of an automobile. These pictures, which appear even more unorganized and enigmatic than his most complex New York images, also relegate human beings to the far distance or feature lone pedestrians rather than crowds.

Photo: Garry Winogrand. New York World’s Fair, 1964. Fundación MAPFRE Collection,-Madrid

Info: Fundación MAPFRE, KBr Photography Center, Avenida Litoral, 30, Barcelona, Spain, Duration: 11/6-5/9/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-20:00, www.fundacionmapfre.org