ART-TRIBUTE:Carte blanche to Anne Imhof, Part III

With her installation “Natures Mortes” at the Palais de Tokyo, Anne Imhof opens up new avenues for her artistic practice that enter into resonance with the history of modern and contemporary art. The various works presented throughout the exhibition, far from offering a conventional history of the still life, dialogue with one another around themes that animate Imhof’s work and beyond (Part I, Part II).

With her installation “Natures Mortes” at the Palais de Tokyo, Anne Imhof opens up new avenues for her artistic practice that enter into resonance with the history of modern and contemporary art. The various works presented throughout the exhibition, far from offering a conventional history of the still life, dialogue with one another around themes that animate Imhof’s work and beyond (Part I, Part II).

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Palais de Tokyo Archive

With “Faust”, Anne Imhof used the German Pavilion in Venice to evoke the absolutes of ‘architecture-state-nation’ and to serve as a backdrop for games of power, submission, and control. In much the same way, she has here stripped the Palais de Tokyo to its bare bones, transforming the building into a territory of resistance and resonance in a response to the brutality of its architecture. Within the Palais de Tokyo, Imhof has created a vast landscape of screens in recycled glass. The vocabulary and the forms that she deploys in Natures Mortes suggest both an urban and domestic environment, a glass maze that hems visitors in even as its transparency allows them to see through its walls. How can privacy and intimacy survive such a multiplication of points of view? A recurrent motif in Anne Imhof’s work, these glass screens constitute a complex architectural ensemble that generates effects of mirroring, doubling and echoing. Between sensory deprivation and perception, these spaces of encounter and confrontation elicit questions as to the stakes of sight and observation. The exhibition “Natures Mortes” is divited in the following sections: “Curve 1”, “Maze”, “Street”, “Curve 2”, “Cinémathèque”, “Wing”, “Ground” and “Stage”.

Adrián Villar Rojas displays in a freezer an assemblage of materials and objects collected in the course of his travels: flowers and vegetables, crustacean shells, beer bottles, electronic devices ripped apart. With this disparate collection frozen in a frosted case, the artist creates an environment in which organic and synthetic, and space and time collide, “with total ignorance of our hierarchies, chronologies or languages, but holding the pathos of a mourning conscience”.

Joan Mitchell paints luminous, abstract landscapes that come to birth somewhere at the interface between the artist’s innermost being and the world around her. Drawing on memories and sensations gradually fading from recollection, her works are the product of a lively gesture that extends across the canvas in shards of exuberant colour. Her landscapes are in perpetual movement.

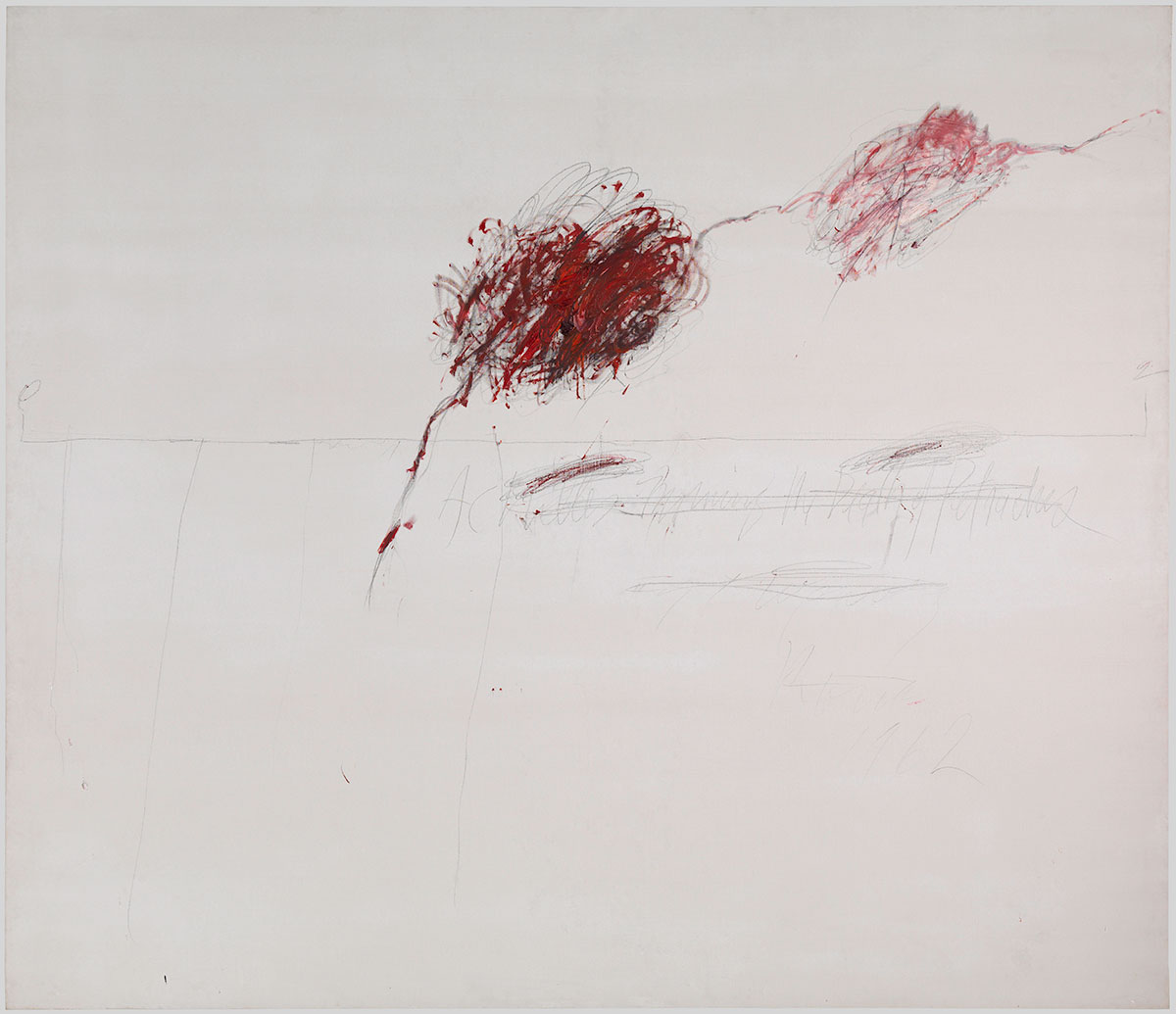

The theme of mourning is omnipresent in Cy Twombly’s painting “Achilles Mourning the Death of Patroclus” (1962). The title alludes to an episode in Homer’s Iliad, when Achilles finds himself weeping the death of his friend Patroclus, killed in the Trojan War. With a radical economy of means, two blood red patches have been smeared by hand across the canvas, to float above an almost invisible horizon line, between earth and heaven, life and death. The crossed out words beneath the abstract forms remind us of the centrality of writing to Twombly’s work: scratches, smudges and stains reflect a deliberate clumsiness that escapes the academic codes of calligraphy.

“La Corazza di Michelangelo” (The Armour of Michelangelo) is a work by Paul Thek directly inspired by a sculpture of Michelangelo’s that represents Giuliano de’ Medici (1526), the Italian artist is among Anne Imhof’s sources of inspiration. In it Thek mimics the way the cuirass is rendered in marble, seemingly fusing with the muscled torso of the model, the body and its protection becoming indistinguishable. Visiting Sicily in 1963, Thek bought from a tourist shop a fake Roman breastplate in plaster. To this he applied dabs of wax that he painted in scarlet and off-white to give an impression of flesh, of muscle and fat – a reversal of roles in which the armour ends up wearing the body.

A leading figure of the anti-form movement, best known for her soft sculptures in latex or plastic that seem to choose their own forms, Eva Hesse left a few remarks about drawing in her diary. It was for her “a nucleus around which to build up the matrices of forms to come”. As for Anne Imhof, drawing for her seems to be both a means of capturing the immediate and the starting point for a protean body of work. It is thus the preferred medium for the study of bodies and movement, and the bearer of a great emotional charge, testifying to a certain romanticism in both artists.

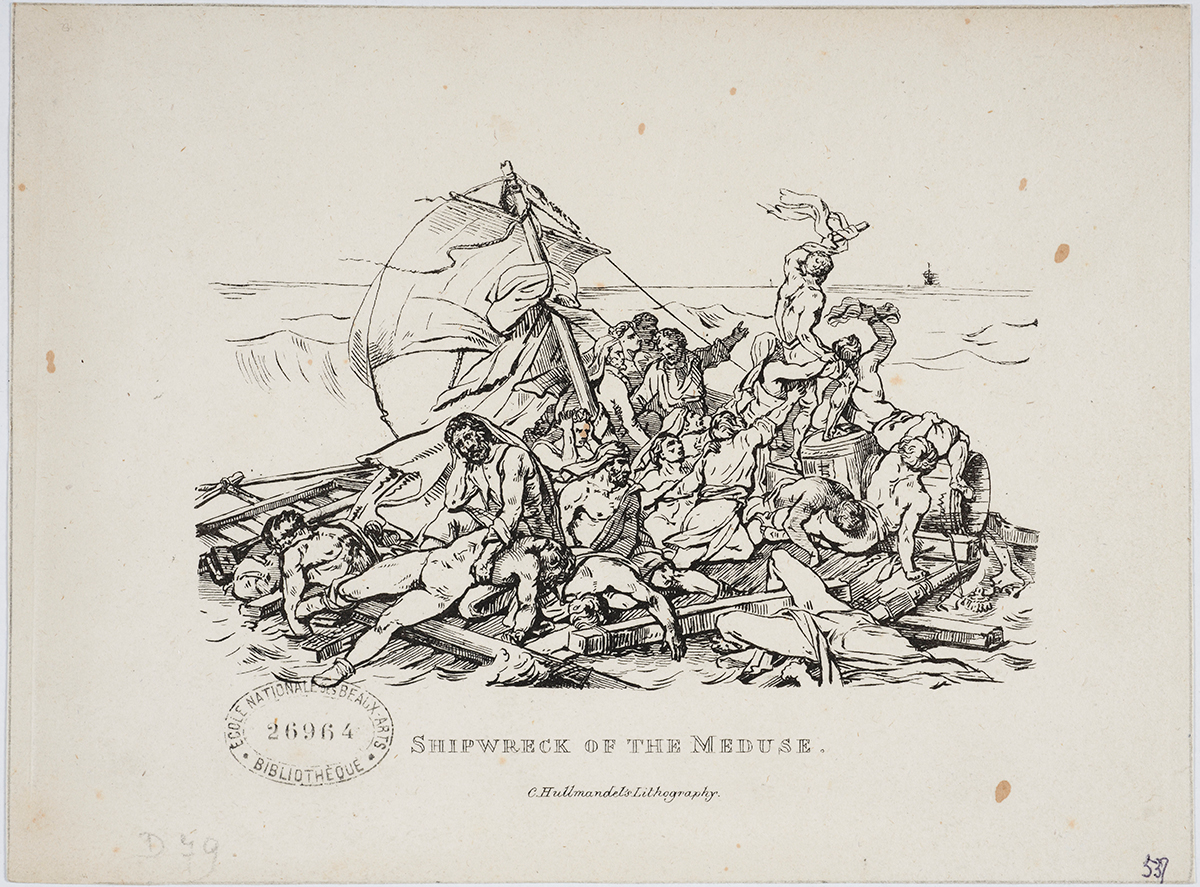

Anne Imhof is fascinated by the drawings and studies of the romantic painter Théodore Géricault. Among them are his anatomical studies of man and horse, which are accompanied by handwritten notes naming the bones, tendons and muscles that he depicts with precision. By inventorying what lay beneath the skin, he came to understand the extension of the leg, the flexing of the knee, the abduction of the shoulder… Such scientific drawings are found among the preparatory studies for “The Raft of the Medusa” (1818-19), for which he obtained supplies from Parisian hospitals, which provided him with a decapitated head and severed limbs that accumulated in his studio. The study of anatomy is a way to extract from the bodies of the dead the principles which animate those of the living.

The photographer Eadweard Muybridge is known for contributing to our understanding of how a horse moves at a gallop, his experiments in chronophotography identifying the position of the limbs at successive moments. Earlier representations proved to be highly unrealistic, as for instance in Théodore Géricault’s “Derby d’Epsom” (1821), in which the horses seem to float in the air. It was in 1878 that Muybridge set up a battery of 12 cameras (later 24) set at equal distances along a track, each activated as the passing horse struck successive tripwires.

Rosemarie Trockel enters the history of art against the grain, as the producer of a proteiform body of work directed against mass production, political violence, and the myth of male genius. In the context of this exhibition, one might see in this sculpture an echo of the 16th-century Dutch still lifes that show butcher’s stalls with their cuts of meat. Trockel’s use of ceramics nonetheless takes us away from that pictorial tradition and back to a form of art long relegated to the rank of craft, rendering invisible the (often female) creative work that it involves.

The Italian architect and engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi is particularly well known for the “imaginary prisons” he published between 1749 and 1750. These 16 architectural views depict fictional constructions together with human occupants and implements of torture. Inspired initially by the vogue for vedute, perspective views of urban landscapes, Piranesi found himself fascinated by the excavations of ancient remains that he visited. Now he no longer wished to represent the contemporary urban environment, but rather to elaborate fantastical visions of the vanished architecture of the past. Piranesi’s prisons are labyrinths, recalling those of Anne Imhof: places that keep humans captive by leading them astray, which imprison not by the deprivation but by the excess of space.

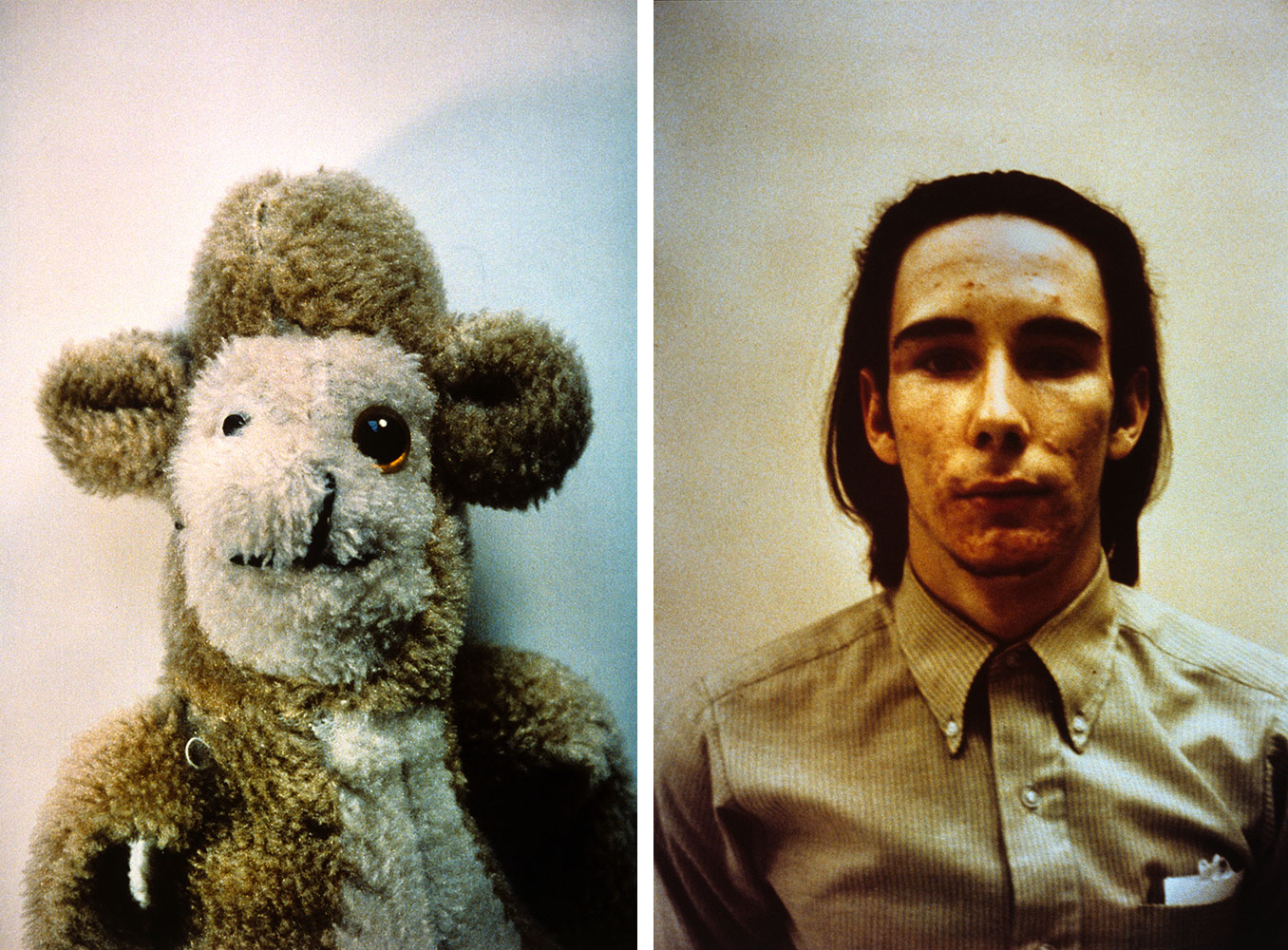

“Ahh… Youth!” is a series of portraits of stuffed animals amongst which artist Mike Kelley has slipped in his own, a photograph from his high-school years. Pimpled by acne, his teenage face echoes the imperfections of the toy animals. Too much loved, they appear before the lens with fur worn and dirty, an eye missing, snout repaired. With these transitional objects, symbolic of the lost continent of childhood, Kelley explores the passage to adulthood, the passions and torments of adolescence. These stuffed animals picked up in second-hand stores suggest both a group of sweet, abandoned animals, and a gang of criminals; in choosing the head-and-shoulders format, Kelley was deploying the code of the American police photograph.

Participating Artists: Anne Imhof, Alvin Baltrop, Mohamed Bourouissa, Eugène Delacroix, Trisha Donnelly, Eliza Douglas, Cyprien Gaillard, Théodore Géricault, David Hammons, Eva Hesse, Mike Kelley, Jutta Koether, Klara Lidén, Joan Mitchell, Oscar Murillo, Eadweard Muybridge, Cady Noland, Precious Okoyomon, Francis Picabia, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Sigmar Polke, Paul B. Preciado, Bunny Rogers, Sturtevant, Yung Tatu, Paul Thek, Wolfgang Tillmans, Rosemarie Trockel, Cy Twombly, Adrián Villar Rojas.

Photo: ADRIÁN VILLAR ROJAS, UNTITLED (FROM THE SERIES « RINASCIMENTO »), 2015-2021), Melon, celery, white shimejis, coriander, white and black grapes, yams, morilles, enoki mushrooms, eggplants, papayas, black radish, pomegranates, lion’s mane mushrooms, Corona beer bottle, passion fruits, citrons, asparagus, pink radish, curly parsley, red cabbages, nameko, grapefruits, 160 × 45 × 57 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery and kurimanzutto, Photo: Aurélien Mole

Info: Curators: Emma Lavigne et Vittoria Matarrese, Music : Eliza Douglas, Sound installation : Eliza Douglas, Anne Imhof, Palais de Tokyo, 13, avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, Duration: 22/5-24/10/2021, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-20:00, www.palaisdetokyo.com

Center: ROSEMARIE TROCKEL, SHUTTER 2, 2010, Ceramic, glazed ; 95 × 68 × 5 cm, Courtesy Sprüth Magers (Berlin, London, Los Angeles); © Rosemarie Trockel, Adagp (Paris), 2021

Right: THÉODORE GÉRICAULT, STUDY OF A SKINNED LEFT ANTERIOR LIMB, SEEN FROM THE FACE (1815) Greasy black chalk and greasy blood / Black chalk, sanguine; 39.7 × 27.6 cm; Coll. Beaux-Arts de Paris (Paris), Inv. EBA1008-8 Photo: © Beaux-Arts de Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Beaux-Arts image of Paris

Center: PAUL THEK, LA CORAZZA DI MICHELANGELO, 1963, Ceramic, earthenware with white cracks from the 1950s, wax; 40 × 30 × 20 cm, Courtesy Deichtorhallen Hamburg – Falckenberg Collection (Hambourg / Hamburg); Photo: © Egbert Haneke. © The Estate of George Paul Thek (New York)

Right: YOUNG TATU, 2020A, 2020, Carpet ; 150 × 80 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: Aurélien Mole