ART-TRIBUTE:Carte blanche to Anne Imhof, Part II

With her installation “Natures Mortes” at the Palais de Tokyo, Anne Imhof opens up new avenues for her artistic practice that enter into resonance with the history of modern and contemporary art. The various works presented throughout the exhibition, far from offering a conventional history of the still life, dialogue with one another around themes that animate Imhof’s work and beyond.

With her installation “Natures Mortes” at the Palais de Tokyo, Anne Imhof opens up new avenues for her artistic practice that enter into resonance with the history of modern and contemporary art. The various works presented throughout the exhibition, far from offering a conventional history of the still life, dialogue with one another around themes that animate Imhof’s work and beyond.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Palais de Tokyo Archive

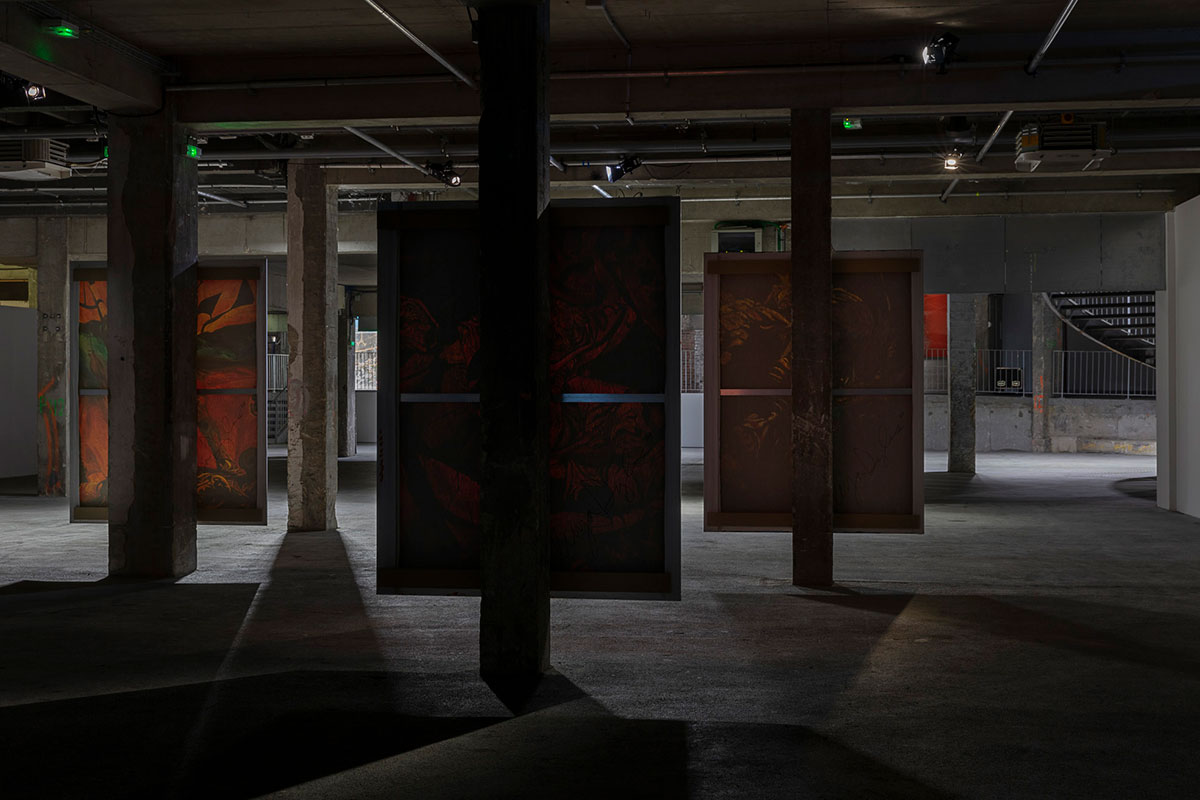

With “Faust”, Anne Imhof used the German Pavilion in Venice to evoke the absolutes of ‘architecture-state-nation’ and to serve as a backdrop for games of power, submission, and control. In much the same way, she has here stripped the Palais de Tokyo to its bare bones, transforming the building into a territory of resistance and resonance in a response to the brutality of its architecture. Within the Palais de Tokyo, Imhof has created a vast landscape of screens in recycled glass. The vocabulary and the forms that she deploys in Natures Mortes suggest both an urban and domestic environment, a glass maze that hems visitors in even as its transparency allows them to see through its walls. How can privacy and intimacy survive such a multiplication of points of view? A recurrent motif in Anne Imhof’s work, these glass screens constitute a complex architectural ensemble that generates effects of mirroring, doubling and echoing. Between sensory deprivation and perception, these spaces of encounter and confrontation elicit questions as to the stakes of sight and observation. The exhibition “Natures Mortes” is divited in the following sections: “Curve 1”, “Maze”, “Street”, “Curve 2”, “Cinémathèque”, “Wing”, “Ground” and “Stage”.

Cady Noland’s work showcases her interest for the more jarring elements in American society, epitomized by such troubling, shadowy figures as Lee Harvey Oswald, Charles Manson, or Patricia Hearst. The latter’s life has inspired Noland’s sculpture “Tanya as a Bandit”. Patricia Hearst, the rich heiress of a media empire, was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a revolutionary organization which she eventually joined, going as far as robbing banks and changing her name to Tanya. Cady Noland’s sculpture makes use of a widely publicized photograph, showing Patricia with a gun in her hand and a determined look in her eyes. The artist has superimposed upon it a bandana, as an evocation of the mythical figure of the cowboy, dual emblem of rebelliousness and of a quest for freedom tinged with violence.

Elaine Sturtevant’s artistic practice grew, as early as the 1960s, from a critical reflection on art history, and on the repetition, diffusion and originality of images. Recreating preexisting works from memory allowed her to bring to light the circularity inherent to any act of creation. Since then, our lives have been inundated by an increasing stream of images, whose exponential surge has been boosted by “our pervasive cybernetic mode, which plunks copyright into mythology, makes origins a romantic notion, and pushes creativity outside the self.

Trisha Donnelly’s video projection brings us face to face with an ungraspable sensory experience. It has no title, offers no familiar shapes nor identifiable materials, and doesn’t seem to appeal to our understanding, but to our imagination. We have to let ourselves be affected by this piece.

Wolfgang Tillmans’ photograph “An der Isar II” creates a slow-down in the exhibition, putting a brake on the sense of acceleration imparted by Anne Imhof’s glass sculpture that draws us in and then Sturtevant’s video with the dog rushing toward us. Showing a body sleeping or lying motionless on a river bank, the large-format black and white image could be just as concerned to capture the beauty of a body as to represent indifference to the fate of the socially excluded. For more than thirty years, Tillman’s work has twinned desire with social critique. Through its representations of the post-punk youth of the 1990s, the Black and LGBTQI+ liberation movements, and more recently the European migrant crisis, it reveals the fragility of the political consensus. Its presence here confers a political dimension on this section of the exhibition, offering an echo to Cady Noland’s sculpture evoking the possibility of youth revolt.

In 2019, Anne Imhof created “Sex” to be shown at Tate Modern, London. There, the two circular Tanks, vestiges of the industrial past of that former power station, housed an exhibition by day and a series of live performances by night. The film transports us into the spaces of the London museum, offering viewers a double take. As it alternates sequences with and without an attendant public, we find ourselves immersed in the performance only to recover our detachment when the crowd vanishes.

In a final acceleration, “The Ride” (2017) by Mohamed Bourouissa, which hybridizes the horse and the car, suggests a final race in this artery. At its end, as a vanishing point, the street opens onto a yawning gap where we are called to gaze into the building’s third level, the bowels of the Palais de Tokyo, and plumb its underground depths. From below, one can perceive the haunting sound of “Phat Free” (1995), a video by David Hammons that shows the artist on a nightly walk on the streets of Harlem, kicking along a metal bucket, whose melancholic ringing fills the whole Palais de Tokyo with its beat.

In Sigmar Polke’s work, the canvas of a painting is not a mere surface, but a testing ground where our way of looking at things is transmuted through experimentation. In “Axial Age” a set of seven paintings created between 2005 and 2007, Polke uses different materials linked to the alchemical and chemical processes of the transformation of matter : light-sensitive products, layered lacquers and varnishes, pigments of gold, silver, lapis-lazuli and malachite.

The work of Francis Picabia’s reproduced in the magazine Cannibale is now lost, the photograph being the only evidence we have of it. When Picabia created this “tableau vivant” in 1920, it would seem that he intended it as an attack on two historic genres of art, the still life and the portrait. His pastiche is at first sight very far from either, presenting us with a stuffed monkey holding in one paw the tail that passes forward between its legs. The inscriptions around the edge designate it as a portrait of CÉZANNE . . . RENOIR . . . and REMBRANDT; below are the words STILL LIFES. The evident irony of the work is typical of Dadaism, an early-20th-century intellectual, literary and artistic movement that sought to put all aesthetic and political conventions into question.

Participating Artists: Anne Imhof, Alvin Baltrop, Mohamed Bourouissa, Eugène Delacroix, Trisha Donnelly, Eliza Douglas, Cyprien Gaillard, Théodore Géricault, David Hammons, Eva Hesse, Mike Kelley, Jutta Koether, Klara Lidén, Joan Mitchell, Oscar Murillo, Eadweard Muybridge, Cady Noland, Precious Okoyomon, Francis Picabia, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Sigmar Polke, Paul B. Preciado, Bunny Rogers, Sturtevant, Yung Tatu, Paul Thek, Wolfgang Tillmans, Rosemarie Trockel, Cy Twombly, Adrián Villar Rojas.

Photo: On the left : ANNE IMHOF, NATURE I (2021), Oil on canvas ; 175 × 250 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers. On the right : ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 210 × 160 cm, Coll. Nunzia e Vittorio Gaddi (Lucca), Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville); © Eliza Douglas, Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

Info: Curators: Emma Lavigne et Vittoria Matarrese, Music : Eliza Douglas, Sound installation : Eliza Douglas, Anne Imhof, Palais de Tokyo, 13, avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, Duration: 22/5-24/10/2021, Days & Hours: Mon & Wed-Sun 10:00-20:00, www.palaisdetokyo.com

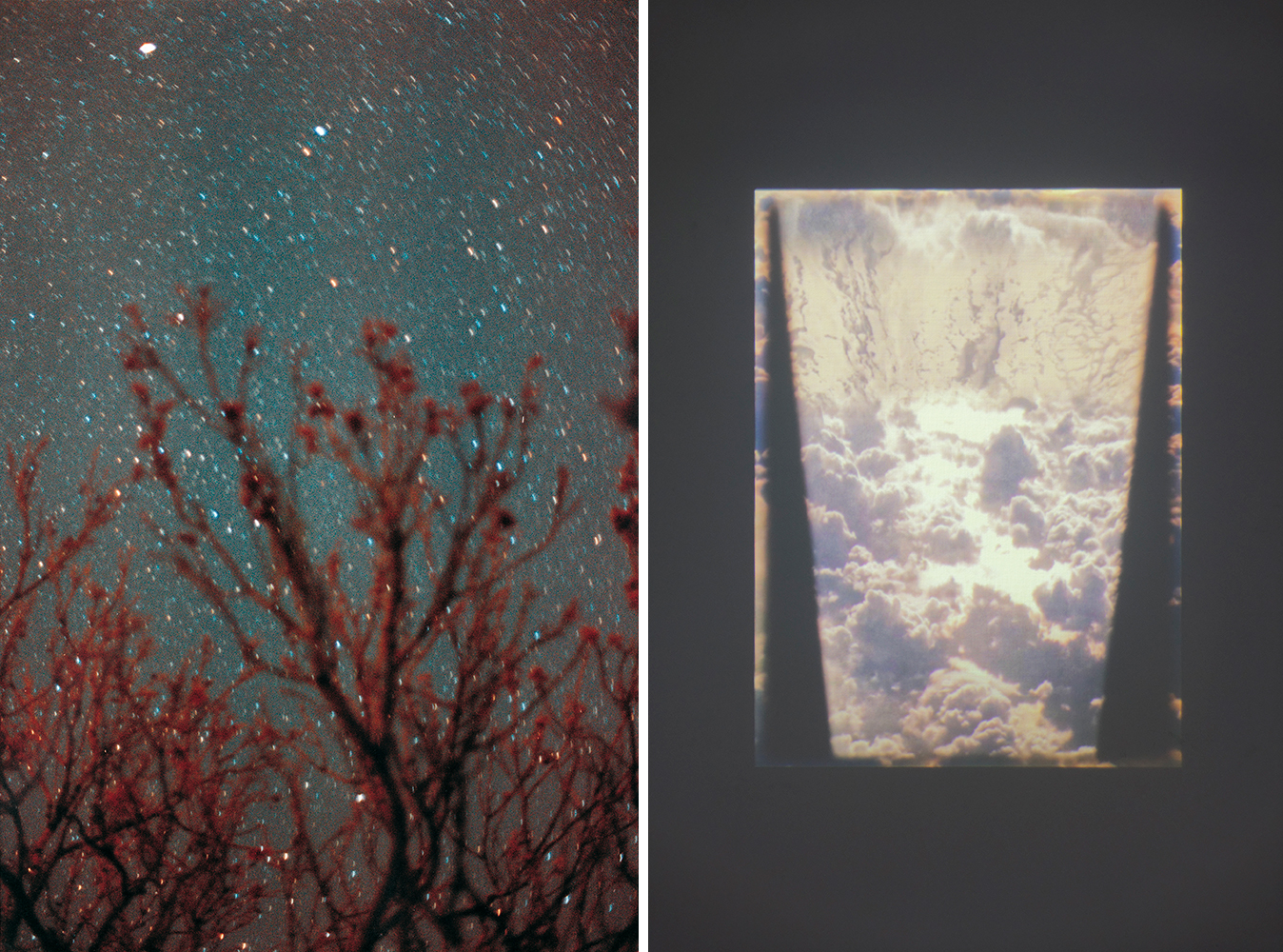

Right : TRISHA DONNELLY, UNTITLED, 2014, Video (color, silent); 7 min 30 s ( loop), Coll. Fondation Louis Vuitton (Paris), Photo credit : Aurélien Mole

ANNE IMHOF, DIVE BOARD (II) (2021), Galvanised steel ; Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Mager

Anne Imhof, Track, 2021, Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers

Up : ELIZA DOUGLAS & ANNE IMHOF, SOUND RAIL II (2021), Steel, speakers, Music by Eliza Douglas, Sound installation by Eliza Douglas and Anne Imhof, Soundtrack : Silver ; Black Metal Mermaid ; The Corner of the Sky; Lucifer’s Lullaby (Trabende Trabanten (Anne’s poem)); Tiny Vixen ; Divide the Water (whipping waves soundtrack); (Ocean sound) , Courtesy of the artists, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers, Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

Right : In the foreground : BUNNY ROGERS, SWANS FILTH MOP (ZOMBIE), 2019, Stained wood, yarn t-shirt, duct tape ; Dimensions variable, Courtesy of the artist and Société (Berlin). In the background : ANNE IMHOF, MAZE, 2021, Steel, glass , Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers, Photo credit : Aurélien Mole

On the right : ANNE IMHOF, STREET (2021), Steel, glass, Courtesy de l’artiste, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers, Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

On the right : DAVID HAMMONS, PHAT FREE (1995-1999), Video transferred to DVD (colour, sound); 5 min 20 s, Coll. S.M.A.K. (Ghent); © David Hammons, Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

![ALVIN BALTROP, THE PIERS (EXTERIOR WITH COUPLE HAVING SEX) (N.D. [1975-1986]), Gelatin silver print ; 11,7 × 18 cm; Courtesy Galerie Buchholz (Berlin, Cologne / Köln, New York)](http://www.dreamideamachine.com/web/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/0101.jpg)

ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 207,9 × 162 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville)

ELIZA DOUGLAS & ANNE IMHOF, VAPE MUSIC (2021), Video, color, sound ; 30 min 4 s, Music Performed by Eliza Douglas and Anne Imhof, Performers : Daniel Birkner, Kwaku Broni, June Won Choi, Jakob Eilinghoff, Bruno Krahl, Mickey Mahar, and Henning Sponholz, Courtesy of the artists, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers

ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 209,4 × 163,2 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville), Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 207,9 × 162 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville)

ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 209,4 × 163,2 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville), Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

Up : ELIZA DOUGLAS & ANNE IMHOF, SOUND RAIL II (2021), Steel, speakers, Music by Eliza Douglas, Sound installation by Eliza Douglas and Anne Imhof, Soundtrack : Silver ; Black Metal Mermaid ; The Corner of the Sky; Lucifer’s Lullaby (Trabende Trabanten (Anne’s poem)); Tiny Vixen ; Divide the Water (whipping waves soundtrack); (Ocean sound), Courtesy of the artists, Galerie Buchholz and Sprüth Magers, Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti

ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 207,9 × 162 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville)

ELIZA DOUGLAS, UNTITLED (2020), Oil on canvas ; 209,4 × 163,2 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris (Romainville), Photo credit : Andrea Rossetti