ART-PRESENTATION: William Eggleston & John McCracken-True Stories

The exhibition “True Stories” is the first that two iconic American artists (William Eggleston and John McCracken) have been featured together. “True Stories” places Eggleston and McCracken into dialogue around their expressive use of color and light, and their distinct versions of American vernacular culture. True Stories is titled after the 1986 film directed by David Byrne “about a bunch of people in Virgil, Texas.” The film explores a fictional place that touches on a certain American spirit, drawing on Eggleston’s work to help describe what Byrne calls, in the introduction to an accompanying book featuring the artist’s photographs, “an existential landscape.” Much of the film is narrated by Byrne as he drives through Virgil.

The exhibition “True Stories” is the first that two iconic American artists (William Eggleston and John McCracken) have been featured together. “True Stories” places Eggleston and McCracken into dialogue around their expressive use of color and light, and their distinct versions of American vernacular culture. True Stories is titled after the 1986 film directed by David Byrne “about a bunch of people in Virgil, Texas.” The film explores a fictional place that touches on a certain American spirit, drawing on Eggleston’s work to help describe what Byrne calls, in the introduction to an accompanying book featuring the artist’s photographs, “an existential landscape.” Much of the film is narrated by Byrne as he drives through Virgil.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: David Zwirner Gallery Archive

Born within five years of one another (John McCracken in Berkeley, California, in 1934, and William Eggleston in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1939) the two artists came of age outside of the dominant centers of the art world, internalizing the spaces and light of the American West and South. Working in sculpture and photography, respectively, each would go on to break with the practices of their contemporaries and challenge the traditional boundaries of their media in search of a new form of expression. Though both artists occupy singular positions within the recent history of American art, they find common ground in their sharp formal sensibilities and distinctive eye for color. McCracken is known for his work that melds the restrained formal qualities of minimalist sculpture with a unique West Coast sensibility expressed through color, form, and finish. For McCracken, color was an integral element of his practice, and he considered similar or even identical forms executed in differing hues to be entirely individuated artworks that engage with their surroundings in a distinct way. Considered the father of modern color photography, Eggleston elevated the medium to the art form that it is recognized as today. Eggleston’s novel pictorial style deftly combines vernacular subject matter with an innate and sophisticated understanding of color, form, and composition. Like McCracken, Eggleston recognized the psychological charge of color and his skilled use of it, along with his democratic and indiscriminate lens, would set him apart from his contemporaries. Both Eggleston and McCracken privileged a way of making art that championed an open relationship to their viewers. Through their own unique visions, both artists eschew fixed meaning, emphasizing the subjective experience of the viewer and granting us access to a private world in which we might recognize a wider one. While formally reductive in their simplified geometric shapes, McCracken’s luminous surfaces are emblematic of a distinctive West Coast approach to minimalism. Unlike his East Coast contemporaries, who considered their own reductive forms to be entirely nonreferential and self-contained, McCracken thought of his work more expansively and in relation to the subjective experience of each viewer and often referred to them as “structural essences of the man-made world.”1 As art historian and curator Robin Clark notes, “In addition to likening them to humans, McCracken described his slotted sculptures prosaically as ‘two-sided, front and back. Like people, buildings, houses, cabinets, refrigerators, ovens, hi-fi, electrical components, cars & trucks, safes, heaters, display cases etc.,’ and more succinctly as ‘mystery containers”. Similarly, Eggleston sought to turn the ordinary into the distinctive, capturing the landscape and character of the American South in Kodachrome colors through a technical approach and visual style more often associated with the evolving snapshot aesthetic of contemporary street photography than the formalist practices of traditional fine art photographers. His images of storefronts, restaurants, homes, cars, and people of the cities, towns, and settings to which he traveled expose an architecture of surfaces in postwar America, while revealing the breadth and individuality of everyday life in often overlooked locations. As Thomas Weski notes, “Eggleston’s photographs connect apparent intimacy with the accessibility of the snapshot. At the same time they preclude a quick and unambiguous interpretation owing to their strange or unfamiliar perspective, the detail chosen, and the subjective control of color: each picture evokes, opens up, different associations for every observer”. When considered together, these works reveal synchronicities between their unique visions: McCracken’s pedestal works and planks can be likened to everyday objects while Eggleston’s photographs convey pure color and form. Found within McCracken’s imbued spirituality and Eggleston’s embrace of the spiritual banal are stories of the American psyche, from the heroic to the mundane. With a career spanning over fifty years, William Eggleston continues to hold a significant influence on contemporary photography and visual culture at large. His 1976 solo exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, , marked one of the first presentations of color photography at the museum. The show and its accompanying catalogue, William Eggleston’s Guide, heralded an important moment in the medium’s acceptance within the art-historical canon, and it solidified the artist’s position as one of its foremost practitioners to this date. John McCracken developed his early sculptural work while studying painting at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland in the late 1950s and early 1960s. While experimenting with increasingly three-dimensional canvases, the artist began to produce objects made with industrial materials, including plywood, sprayed lacquer, and pigmented resin, creating the highly reflective, smooth surfaces for which he was to become known. In 1966, McCracken generated his signature sculptural form: the plank, a narrow, monochromatic, rectangular board format that leans at an angle against the wall (the site of painting), while simultaneously entering into the three-dimensional realm and physical space of the viewer.

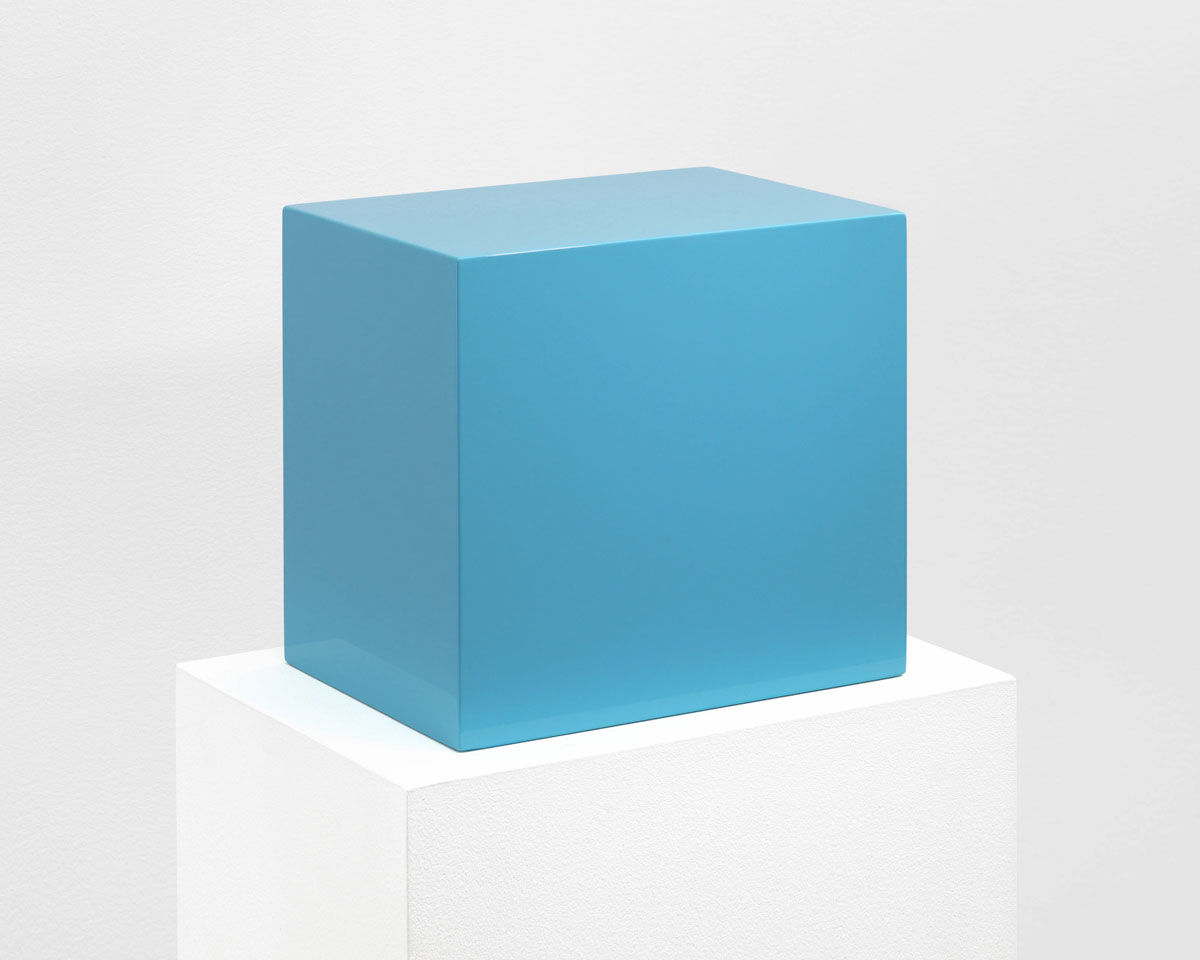

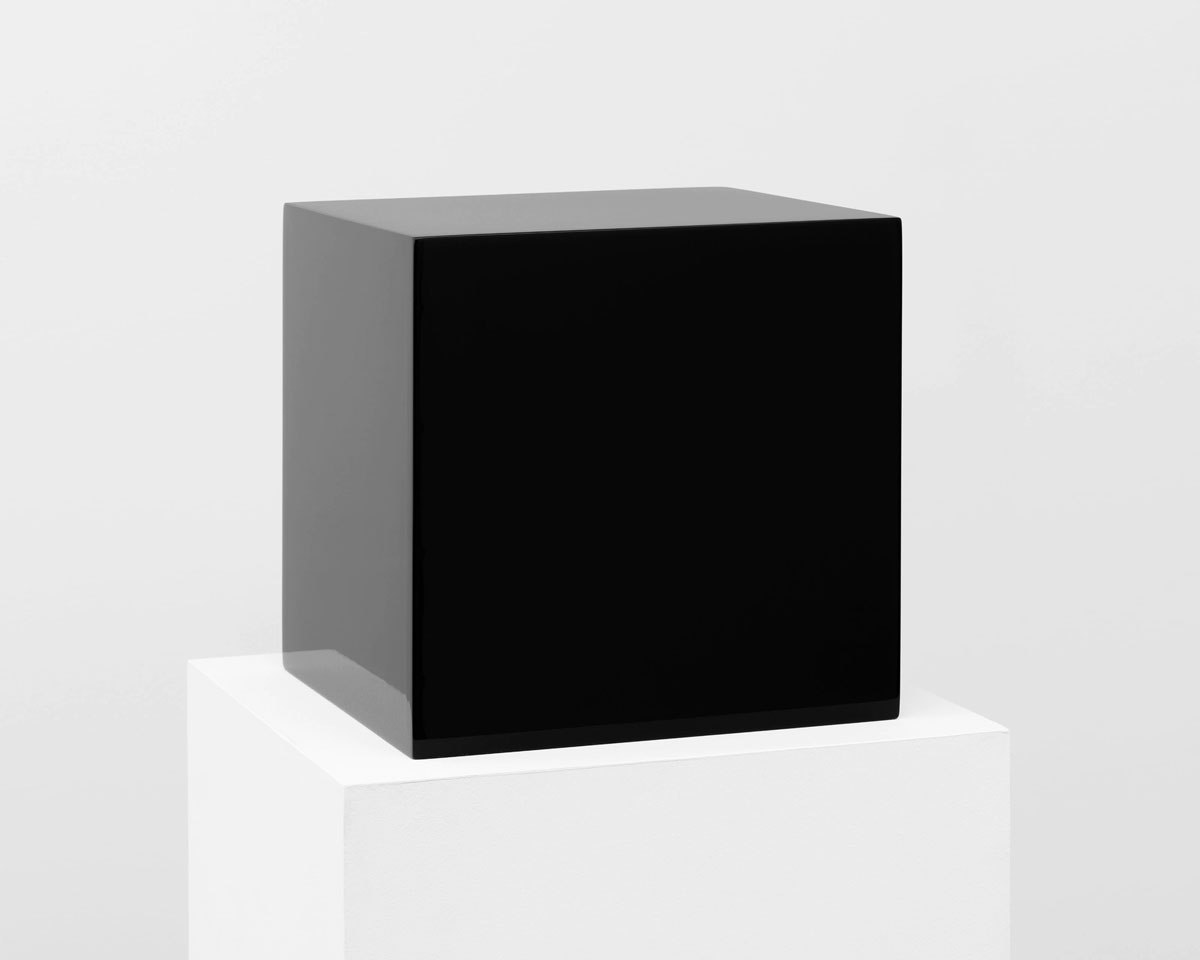

Photo: John McCracken, Untitled (Red Block), 1966, Lacquer, fiberglass, and plywood, 8 x 11 x 10 inches / 20.3 x 27.9 x 25.4 cm, © John McCracken, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery

Info: David Zwirner Gallery, 34 East 69th Street, New York, Duration: 9/3/2021- , Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00 Schedule Your Visit, www.davidzwirner.com

Right: John McCracken, Untitled (Red Plank), 1976, Polyester resin, fiberglass, and plywood, 84 1/8 x 12 x 1 1/4 inches / 213.7 x 30.5 x 3.2 cm, © John McCracken, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery

Center: John McCracken, Think Pink, 1967, Polyester resin, fiberglass, and plywood, 104 1/2 x 18 1/8 x 3 1/8 inches (265.4 x 46 x 7.9 cm, © John McCracken, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery

Right: John McCracken, John McCracken, Untitled, 1976, Polyester resin, fiberglass, and plywood, 84 x 12 x 1 1/4 inches / 213.4 x 30.5 x 3.2 cm, © John McCracken, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery