TRACES: Robert Morris

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the central figures of Minimalism, Robert Morris (9/2/1931-28/11/2018). Through both his own sculptures of the 1960s and theoretical writings, Morris set forth a vision of art pared down to simple geometric shapes stripped of metaphorical associations, and focused on the artwork’s interaction with the viewer. However, in contrast to Donald Judd and Carl Andre, Morris had a strikingly diverse range that extended well beyond the Minimalist ethos and was at the forefront of other contemporary American art movements as well, most notably, Process art and Land art. his column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the central figures of Minimalism, Robert Morris (9/2/1931-28/11/2018). Through both his own sculptures of the 1960s and theoretical writings, Morris set forth a vision of art pared down to simple geometric shapes stripped of metaphorical associations, and focused on the artwork’s interaction with the viewer. However, in contrast to Donald Judd and Carl Andre, Morris had a strikingly diverse range that extended well beyond the Minimalist ethos and was at the forefront of other contemporary American art movements as well, most notably, Process art and Land art. his column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

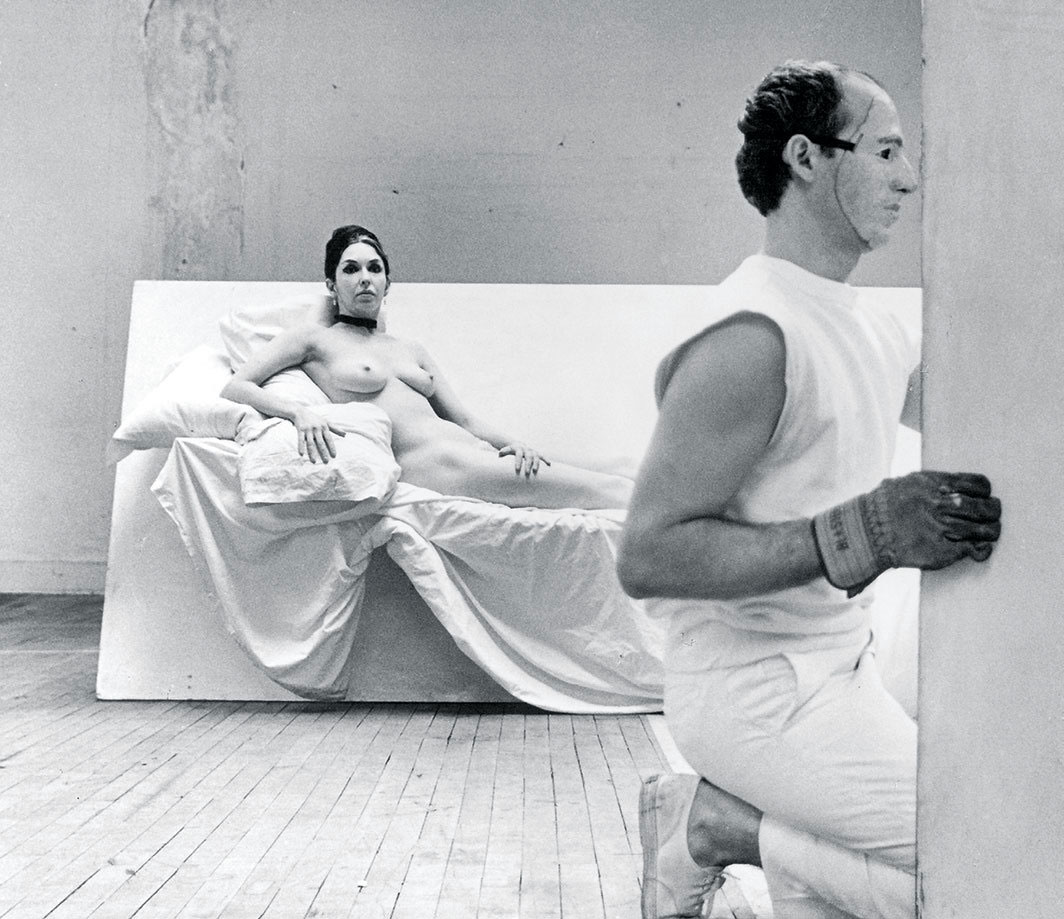

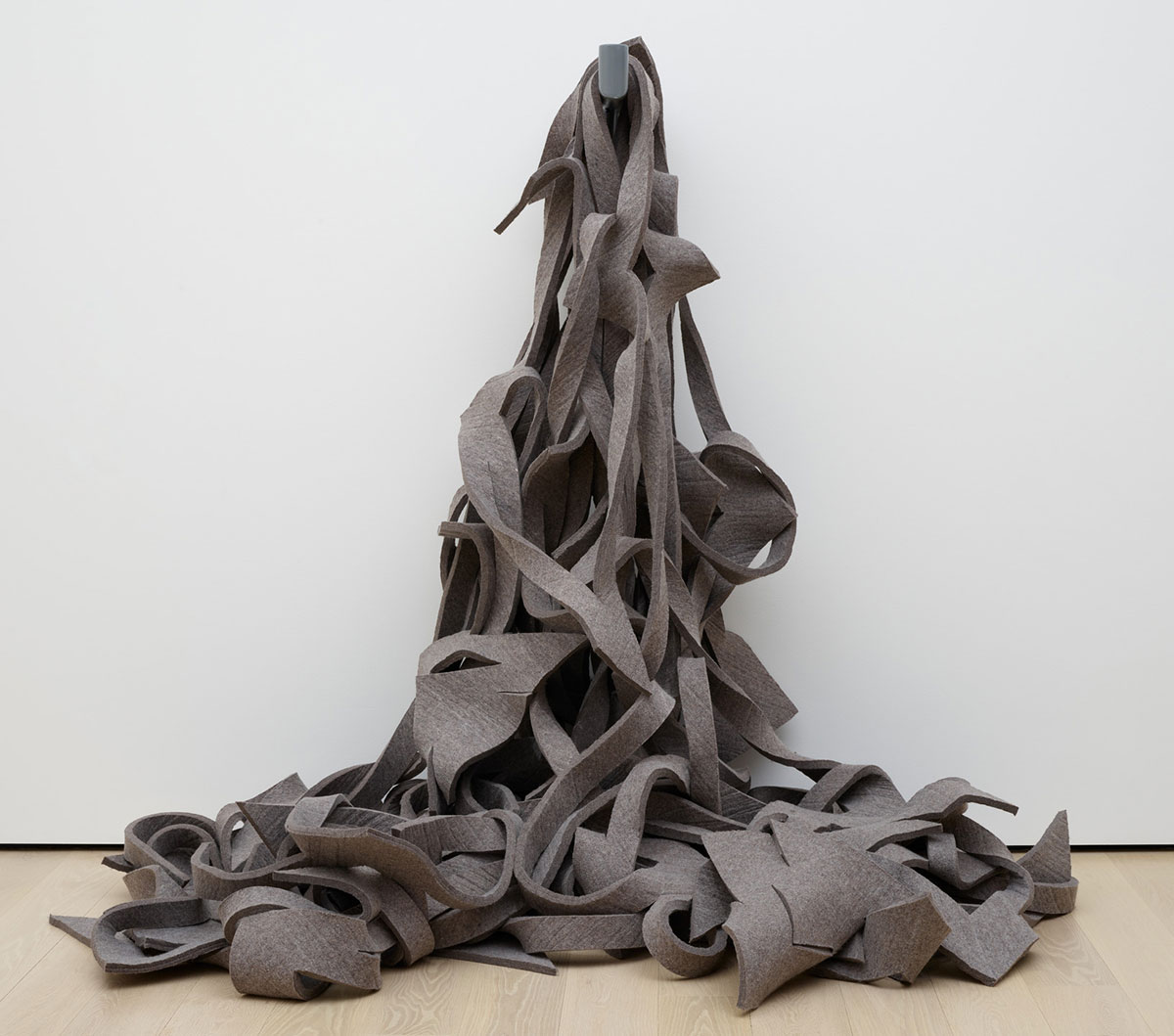

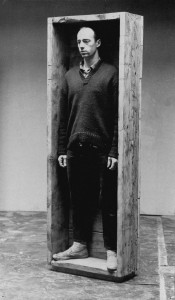

Robert Morris grew up in a suburban area of Kansas City. Early in life, he began reproducing comic strip images, a habit that helped him discover a talent for drawing. A flexible outlook at his elementary school allowed him to spend additional time honing his artistic skills. He also participated in a weekend enrichment program that encouraged the students to sketch artwork in the local Nelson Gallery (now the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art) and draw at the art studios of the Kansas City Art Institute. Morris took classes at the University of Kansas City and the Kansas City Art Institute in 1948. He transferred to the California School of Fine Arts in 1951, but only stayed for a semester before joining the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. Upon his return to the States in 1953, he enrolled at Reed College in Oregon to study psychology and philosophy. Two years later, he returned to California to continue painting full time. During his student years, Morris painted monochromatic abstract landscapes influenced by Clyfford Still, who had taught at the California School of Fine Arts. After leaving Reed College, Morris continued producing large-scale abstract pieces, but this time following the methods of Jackson Pollock, such as painting on the floor, using a scaffold to suspend himself over the canvas. Via such experimentation Morris developed an interest in the working process itself. Morris ultimately abandoned painting in the late 1950s, troubled by a feeling of disconnect between the end result of painting and the actions involved in its production. Through his wife, the dancer Simone Forti, Morris became more involved with film and performance art. For the next several years, the couple organized theater workshops that explored the possibilities of movement and improvisation. In 1960, Morris moved to New York and enrolled at Hunter College to study art history. Having abandoned painting, he started to build sculptures in plywood. One of the first pieces completed was “Box with the Sound of Its Own Making” (1961), a wooden cube accompanied by a recording of the sounds produced during its construction. The way in which the object itself was combined with process gave Morris a sense of satisfaction he was unable to realize in painting. Over the next few years, he continued to produce art that focused on the role of language, its relationship to the body and other underlying concepts rather than the physical object itself. His first solo exhibition in New York took place in 1963 at the Green Gallery. Aside from Donald Judd, who recognized the Minimalist elements of Morris’s work, most critics responded negatively to the works in the show, perceiving them as insignificant and overly aggressive. Also in 1963, Morris resumed his exploration of theater and movement, choreographing his first dance performances in New York. “Site” (1964), executed with Carolee Schneemann, is closely related to Morris’s contemporary sculpture, in that it focuses on a continuous series of actions. In this piece, Morris removed a pile of wooden slabs one by one to reveal Schneemann, posed in the manner of Manet’s Olympia. Beginning in 1966, Morris published the first of several important articles in ArtForum that helped articulate the intentions of his own sculpture, as well as the ideas underlying key art movements. The series, entitled “Notes on Sculpture” is among the best known of his writings, and identified him as one of the central figures of Minimalism. In these essays, Morris rejected the concept of the uniqueness of the art object, instead emphasizing the importance of the artwork’s relationship to the viewer. This is seen in works such as “Untitled (L-Beams)” (1965), consisting of identical L-shaped constructions arranged in different positions, making them appear to be of different shapes and sizes depending on the position of the viewer. Progressing in his aim to dissolve the object, Morris worked with commonplace materials, not unlike Arte Povera artists in style and intention. “Untitled” (1967) is made of pieces of felt cut into strips, which spill haphazardly onto the floor. The resulting object is random, without a definite shape or form. The ordinariness of the material makes the object seem even less substantial. To demonstrate his “Anti-Form” principles, in 1968, Morris organized the exhibition 9 at the Leo Castelli Warehouse, which included the work of Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman and Richard Serra. Morris has continued to develop these ideas in his work in performance art, and has installed several site-specific installations in the United States and Europe. From the late 1970s to the present, he has experimented with different types of media, including mirrors, Hydrocal (a brand of Plaster of Paris), and even painting. His themes have been almost as varied, ranging from war to memory to feminism. In particular, Morris has widely explored blindfolded drawing in the “Blind Time” series, begun in 1973. He executed the first series of drawings with his hands dipped in a mixture of oil and graphite, following a set of previously defined rules to create the image; subsequent drawings in a related series were created by a blind woman following the artist’s instructions. Other pieces addressed his disillusionment with the political establishment, a recurring theme in his more recent work. Throughout the next decade, Morris continued to work with free-form materials in order to deconstruct conventional categories of the art object. He slowly dismantled his piece “Continuous Project Altered Daily” (1969), composed of waste materials found in construction sites, until nothing was left except remnants of dirt. The ephemerality of this work was also explored in his steam pieces, such as “Steam Work for Bellingham-II” (1974). In both of these works, the end result is such that photographs are the only records of their existence. By subverting the conventional notion of art as a tangible product of a series of actions, Morris’s Anti-Form and other Post-Minimal pieces expanded the possibilities of what art could be. He passed away in 2018, at the age of 87, from pneumonia in Kingston, New York.

Robert Morris grew up in a suburban area of Kansas City. Early in life, he began reproducing comic strip images, a habit that helped him discover a talent for drawing. A flexible outlook at his elementary school allowed him to spend additional time honing his artistic skills. He also participated in a weekend enrichment program that encouraged the students to sketch artwork in the local Nelson Gallery (now the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art) and draw at the art studios of the Kansas City Art Institute. Morris took classes at the University of Kansas City and the Kansas City Art Institute in 1948. He transferred to the California School of Fine Arts in 1951, but only stayed for a semester before joining the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. Upon his return to the States in 1953, he enrolled at Reed College in Oregon to study psychology and philosophy. Two years later, he returned to California to continue painting full time. During his student years, Morris painted monochromatic abstract landscapes influenced by Clyfford Still, who had taught at the California School of Fine Arts. After leaving Reed College, Morris continued producing large-scale abstract pieces, but this time following the methods of Jackson Pollock, such as painting on the floor, using a scaffold to suspend himself over the canvas. Via such experimentation Morris developed an interest in the working process itself. Morris ultimately abandoned painting in the late 1950s, troubled by a feeling of disconnect between the end result of painting and the actions involved in its production. Through his wife, the dancer Simone Forti, Morris became more involved with film and performance art. For the next several years, the couple organized theater workshops that explored the possibilities of movement and improvisation. In 1960, Morris moved to New York and enrolled at Hunter College to study art history. Having abandoned painting, he started to build sculptures in plywood. One of the first pieces completed was “Box with the Sound of Its Own Making” (1961), a wooden cube accompanied by a recording of the sounds produced during its construction. The way in which the object itself was combined with process gave Morris a sense of satisfaction he was unable to realize in painting. Over the next few years, he continued to produce art that focused on the role of language, its relationship to the body and other underlying concepts rather than the physical object itself. His first solo exhibition in New York took place in 1963 at the Green Gallery. Aside from Donald Judd, who recognized the Minimalist elements of Morris’s work, most critics responded negatively to the works in the show, perceiving them as insignificant and overly aggressive. Also in 1963, Morris resumed his exploration of theater and movement, choreographing his first dance performances in New York. “Site” (1964), executed with Carolee Schneemann, is closely related to Morris’s contemporary sculpture, in that it focuses on a continuous series of actions. In this piece, Morris removed a pile of wooden slabs one by one to reveal Schneemann, posed in the manner of Manet’s Olympia. Beginning in 1966, Morris published the first of several important articles in ArtForum that helped articulate the intentions of his own sculpture, as well as the ideas underlying key art movements. The series, entitled “Notes on Sculpture” is among the best known of his writings, and identified him as one of the central figures of Minimalism. In these essays, Morris rejected the concept of the uniqueness of the art object, instead emphasizing the importance of the artwork’s relationship to the viewer. This is seen in works such as “Untitled (L-Beams)” (1965), consisting of identical L-shaped constructions arranged in different positions, making them appear to be of different shapes and sizes depending on the position of the viewer. Progressing in his aim to dissolve the object, Morris worked with commonplace materials, not unlike Arte Povera artists in style and intention. “Untitled” (1967) is made of pieces of felt cut into strips, which spill haphazardly onto the floor. The resulting object is random, without a definite shape or form. The ordinariness of the material makes the object seem even less substantial. To demonstrate his “Anti-Form” principles, in 1968, Morris organized the exhibition 9 at the Leo Castelli Warehouse, which included the work of Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman and Richard Serra. Morris has continued to develop these ideas in his work in performance art, and has installed several site-specific installations in the United States and Europe. From the late 1970s to the present, he has experimented with different types of media, including mirrors, Hydrocal (a brand of Plaster of Paris), and even painting. His themes have been almost as varied, ranging from war to memory to feminism. In particular, Morris has widely explored blindfolded drawing in the “Blind Time” series, begun in 1973. He executed the first series of drawings with his hands dipped in a mixture of oil and graphite, following a set of previously defined rules to create the image; subsequent drawings in a related series were created by a blind woman following the artist’s instructions. Other pieces addressed his disillusionment with the political establishment, a recurring theme in his more recent work. Throughout the next decade, Morris continued to work with free-form materials in order to deconstruct conventional categories of the art object. He slowly dismantled his piece “Continuous Project Altered Daily” (1969), composed of waste materials found in construction sites, until nothing was left except remnants of dirt. The ephemerality of this work was also explored in his steam pieces, such as “Steam Work for Bellingham-II” (1974). In both of these works, the end result is such that photographs are the only records of their existence. By subverting the conventional notion of art as a tangible product of a series of actions, Morris’s Anti-Form and other Post-Minimal pieces expanded the possibilities of what art could be. He passed away in 2018, at the age of 87, from pneumonia in Kingston, New York.