ART CITIES:Basel-Joachim Bandau

Like that of many of his peers, Joachim Bandau’s work is uncompromising, politicized, antigustatory, and academic-he was a professor of sculpture at both Aachen and Munster. Well known in Germany but rarely shown abroad, Bandau embodies the enlightened nihilism of postwar German art. Like many in Cologne in the mid-1960s, Bandau was influenced by Rudolf Zwirner’s and Konrad Fischer’s exhibitions of Pop Art, but he responded with a Frankfurt School edge

Like that of many of his peers, Joachim Bandau’s work is uncompromising, politicized, antigustatory, and academic-he was a professor of sculpture at both Aachen and Munster. Well known in Germany but rarely shown abroad, Bandau embodies the enlightened nihilism of postwar German art. Like many in Cologne in the mid-1960s, Bandau was influenced by Rudolf Zwirner’s and Konrad Fischer’s exhibitions of Pop Art, but he responded with a Frankfurt School edge

By Dimitri Lempesis

Photo: Kunsthalle Basel Archive

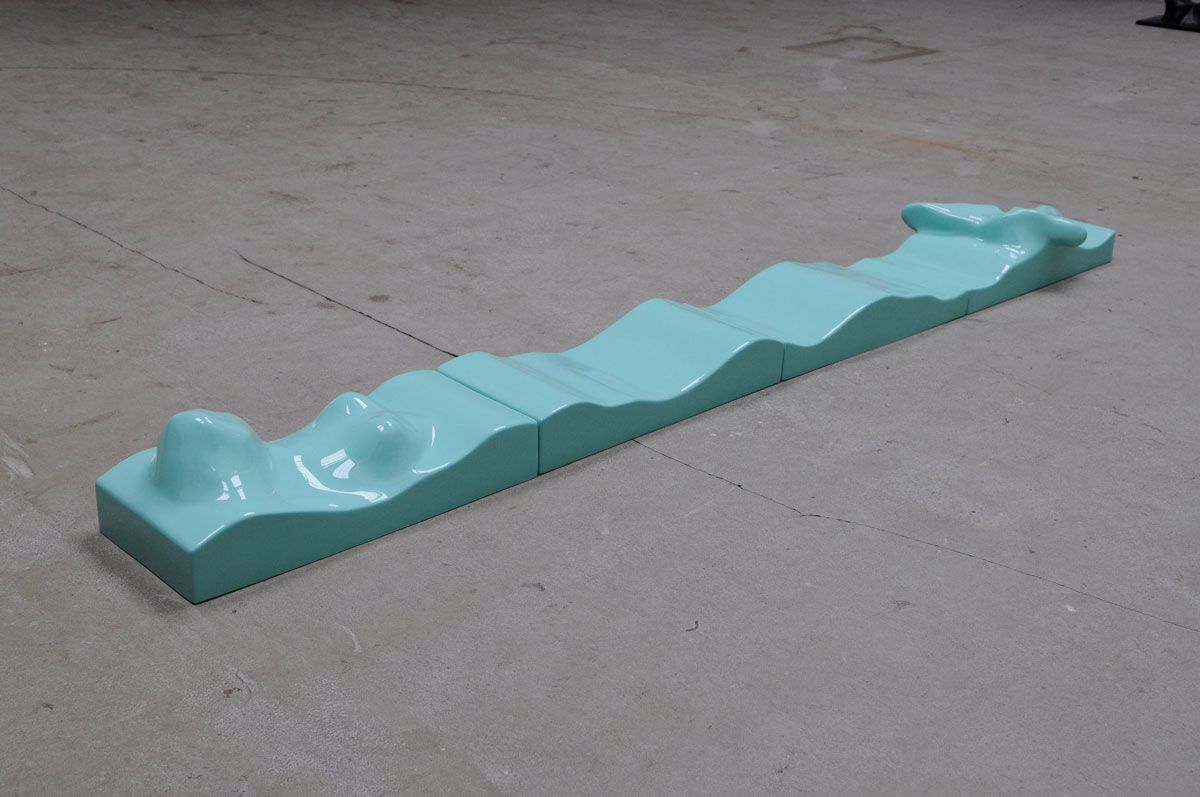

Joachim Bandau belongs to a protean group of German artists, along with Gerhard Richter, Joseph Beuys, and Imi Knoebel, who came out of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1961. Groundbreaking his exploration of form, in the late 70s, Bandau literally moved sculpture from above ground to underground. As with Carl Andre’s development of the floor sculpture, and Bruce Naumann’s concrete casting of the empty space under his chair, this new art form “Bodenskulptur” (Floor Sculpture), provided Bandau with an independent and important position. At once technoid and bodily, minimal and monstrous, often with spouts or hoses that resemble weirdly organic orifices and tentacles, the early sculptural works by Joachim Bandau remain as strange and singular today as when he first made them. An overview of the artist’s still relatively little-known sculptures and drawings from the period 1967 – 1974 is on view in the exhibition “Die Nichtschönen, Works 1967–1974” at Kunsthalle Basel. The sculpture “Silbernes Monstrum” (1970-71) belongs to a series of mobile sculptures made from fiberglass that Bandau has been creating since the late 1960’s. An aggregate of diverse modules, “Silbernes Monstrum” resembles a hybrid of man, machine, and design-object. Something profoundly dystopian inhabits Joachim Bandau’s post-war “Figures, Machines, Monsters” – as he calls the shiny enameled, anthropomorphic plastic sculptures that date from the late 1960s through the early 1970s. Fitted with hoses, bathroom fixtures or shower heads that lend the objects the appearance of self-maintaining systems, the sculptures have been perceived by Rolf Wedewer as “golem figures”. As crosses between technical device and anthropomorphic form, they have elicited a great deal of confusion, in part because they turned standard conceptions of sculpture upside down. When they originally appeared, Hanno Reuther described the uncanny quality of the works as “terror disguised in slick design”. Their machine-like movements, size and of course the titles, by means of which reference was made to the threatening, destructive force of technology were interpreted as a warning that some day machines could somehow run amok and assume dominance over humankind. According to this view, Bandau’s objects are signs of the time, reactions to the political climate in post-war Germany, or even direct, ironic commentaries to contemporary political events. Bandau’s objects are not, however, rooted in time, but extend far beyond it. They cast common sculptural conventions aside and in surface aesthetic and materiality have more to do with design – a reference that many artists, from Joep van Lieshout to Anselm Reyle, now take for granted. Bandau emphasizes this disregard for norms in another small, but in its effect quite radical gesture: he places some of his objects on wheels. In this way the division between applied and fine art is placed in question, as objects on wheels were then generally considered furniture or vehicles. In this context the inclusion of Badau’s “Kabinenmodelle“ made in 1973 in the Daimler Benz AG factory in Sindelfingen, Germany with the support of a grant from the Federation of German Industries – in the Utopian Design section of documenta 6 seem completely logical from the present perspective. In Bandau’s work the figurative element does not just provide the form, it is the substance itself, as he often used parts from mannequins as construction material for his sculptures. To what extent Bandau’s artistic strategies differ from Donald Judd’s objectives is made clear in the draft sketches that he made for each sculpture and that he considers works of art in their own right. These sketches demonstrate that the artist hardly identified with the aesthetic agenda of the intellectual minimal art movement. On the contrary, in the sketch-es we recognize how Bandau worked out the proportions, shapes and mechanics of each individual sculpture and how the objects emerged from the dynamics of this development process –something that characterizes all of his work. The spectrum of his creations, which range from watercolors to the series of enameled wood wall objects he called “Bagan Lackarbeiten” [Bagan Lacquer Pieces], reveals his enduring, ever expanding search for innovative sculptural forms, which he has also begun to transfer to painting.

Photo: Joachim Bandau, Ophelia, badewassergrün, 1967, © Joachim Bandau, Courtesy the artist and Kunsthalle Basel

Info: Kunsthalle Basel, Steinenberg 7, Basel, Duration: 29/1-18/4/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed & Fri 11:00-18:00, Thu 11:00-19:00, Sat-sun 11:00-17:00, www.kunsthallebasel.ch

Right: Joachim Bandau Wasserwerfer, 1974, © Joachim Bandau, Courtesy the artist and Kunsthalle Basel

Right: Installation view, Joachim Bandau Ungestalt, Kunsthalle Basel, 2017, view on “Der Tänzer” (1968), Photo: Philipp Hänger/Kunsthalle Basel