ART CITIES:Paris-Iván Navarro

Born in 1972 in Santiago, Iván Navarro grew up under the Pinochet dictatorship. He uses light as his raw material, turning objects into electric sculptures and transforming the exhibition space by means of visual interplay. His work is certainly playful, but is also haunted by questions of power, control and imprisonment. The act of usurping the minimalist aesthetic is an ever-present undercurrent, becoming the pretext for understated political and social criticism.

Born in 1972 in Santiago, Iván Navarro grew up under the Pinochet dictatorship. He uses light as his raw material, turning objects into electric sculptures and transforming the exhibition space by means of visual interplay. His work is certainly playful, but is also haunted by questions of power, control and imprisonment. The act of usurping the minimalist aesthetic is an ever-present undercurrent, becoming the pretext for understated political and social criticism.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Le Centquatre Archive

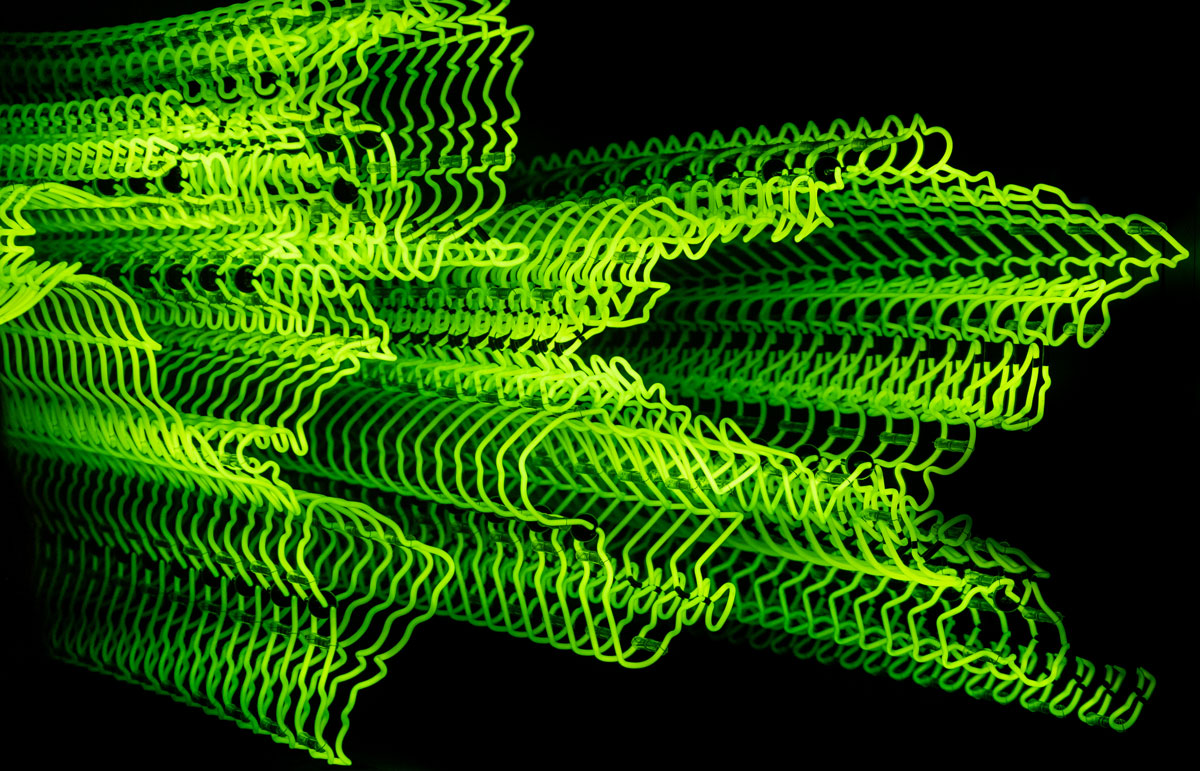

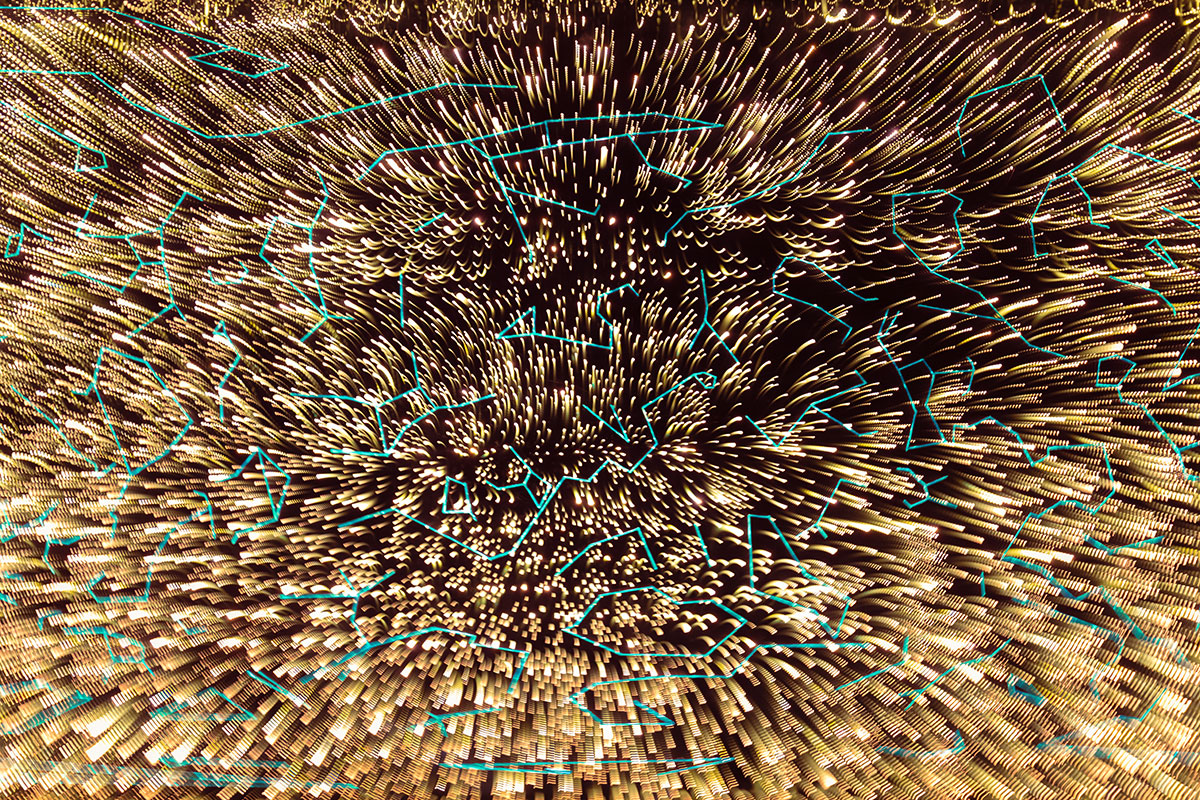

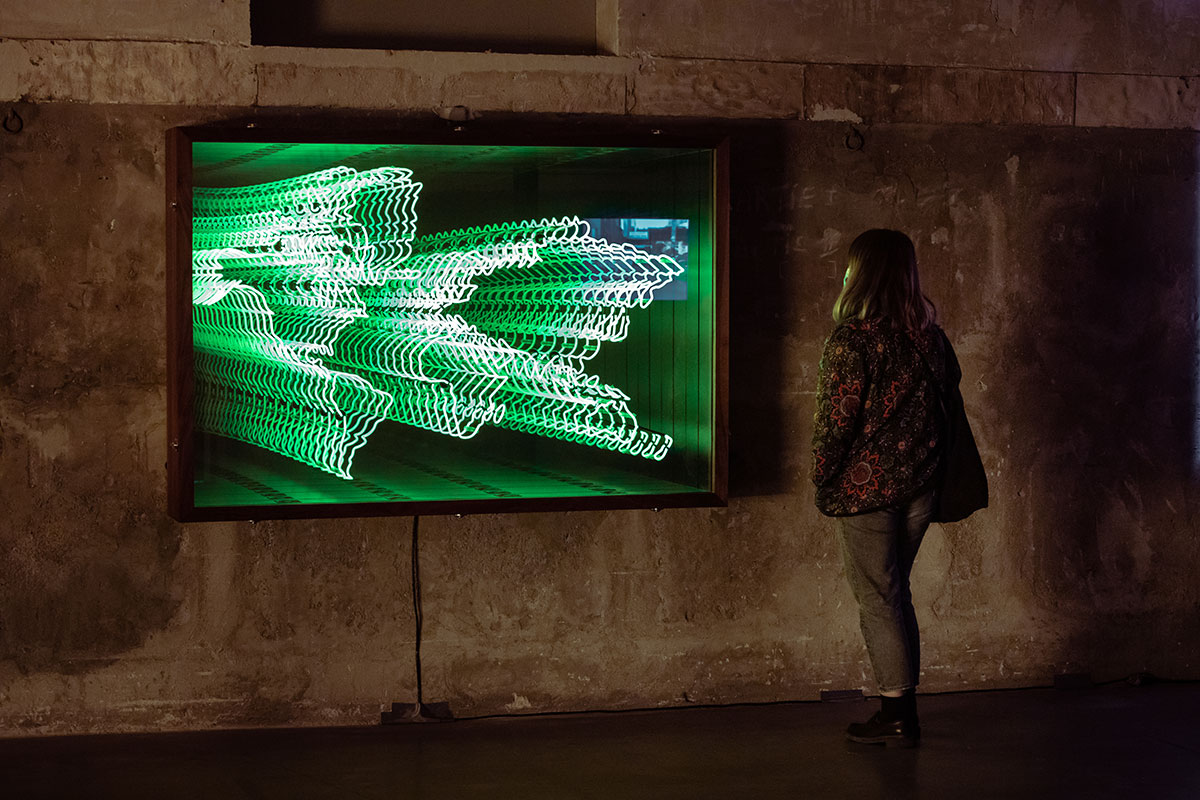

“Planetarium” offers a retrospective look at over 15 years, with about 20 works. With this exhibition Iván Navarro immerses us in a constellation of videos, sculptures and other luminous and audio objects. Celestial and terrestrial bodies merge to better apprehend the mechanisms of power in the light of our metaphysical obsessions, such as identity and memory. Iván Navarro is interested in confronting the trauma of living in Chile under Pinochet’s military dictatorship. While the artist recalls from childhood the persistent fear of “being disappeared”—the fate of many political dissidents, —it was not until he relocated to New York City in 1997 that he began to learn more about the extent of human rights abuses in his country, and the subject now forms the core of his practice. Navarro uses electric light as his primary medium, making politically charged sculptures and installations that address the violence inflicted by the Chilean state. On a local level, his works refer directly to crimes perpetrated by the country’s military regime, but some also reflect his concerns about global issues, addressing, for example, capital punishment in the United States. Navarro appropriates the austere visual language of Minimalism, in particular that of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent-light sculptures—and imbues it with explicit and critical political resonance. The centerpiece of his exhibition at the Venice Biennale (2009) was “Death Row” (2006), an installation of colorful light-framed doors that correspond to the monochrome panels in Ellsworth Kelly’s “Spectrum” (1969). Navarro also engages the history of early twentieth-century modernism in works such as “Red and Blue Electric Chair” (2006), a neon version of Dutch designer Gerrit Rietveld’s famous chair from 1918; Navarro’s chair unsettles the original’s utopian aspirations through a grim allusion to electrocution. The viewer’s body plays a central role in Navarro’s work, in sculptures resembling furniture and in immersive room-size installations. Many of his works entail a kind of perceptual game playing, provoking a phenomenological confrontation via accounts of military abuses in which the viewer is implicated, both sensorially and psychologically. “Dónde están?” (2007) is a large installation with white fluorescent-light letters covering the floor of an otherwise darkened gallery. Visitors must hunt among these for the names of perpetrators of human rights violations during the Chilean dictatorship, few of whom were ever sentenced. Similarly, the large-scale sculpture “Criminal Ladder” (2005) features the name of a different perpetrator on each rung, visualizing the scope of criminal activity in the country. His series “Nowhere Man” takes as a starting point the pictograms conceived by German designer Otl Aicher’s for the infamous 1972 Munich Olympic Games. With a simple “alphabet” of sticks and circles, they schematically represent the main Olympic disciplines: swimming, boxing, football, diving etc. Each figure is made of ordinary mass-produced light fixtures. Seemingly cold and technical, they were however built according to the “ideal proportions” theorized by Leonardo Da Vinci. This attempt to recreate a perfect system of representation and beauty with every day, mundane objects, reveals the complex connections between our humanistic heritage and modernism, between the body and post-industrial society. Through these ghostly, standardized athletes from “nowhere”, Iván Navarro questions the ideological meaning of the Olympic ideal and its universal pretense. As he explains of the five intertwined rings representing the Olympic Games. The “Music Room IV” is part of an ongoing series of constructed environments for active listening, created in collaboration with artist Courtney Smith. Here, the artists have created a wooden fort-like sculpture whose latticed exterior is paneled with album covers from all over the world, each one a representation of revolutionary outcry. The other side of the sculpture reveals a dark, padded concavity for visitors to nestle and yield to the experience of listening. Speakers pipe music deep into the nook of the sculpture, creating a concentrated listening environment within, yet sheltered from, the visual cacophony of the musical light sculptures. The music played is the music seen, a continuous loop of songs of universal protest and celebration which in sum form a unified voice of human resistance in the face of authoritarian oppression.

Photo: Iván Navarro, Planetarium, Exhibition view Le Centquatre-Paris, 2021, Courtesy the artist and Le Centquatre

Info: Le Centquatre, 5 rue Curial, Paris, Duration: 9/1-28/2/2021, Days & Hours: Wed-Sun 14:00-19:00 (In accordance with recent government guidance, Le Centquatre is temporarily closed until further notice), www.104.fr