ART CITIES:Paris-Thomas Ruff

With his manipulations of photographs from many different sources, Thomas Ruff comments in an incredibly clever way on how we see images in a digitalized world. Through his handling of digital image processing, he confronts us with a critical examination of the image material he uses and its historical, political, and epistemological significance,

With his manipulations of photographs from many different sources, Thomas Ruff comments in an incredibly clever way on how we see images in a digitalized world. Through his handling of digital image processing, he confronts us with a critical examination of the image material he uses and its historical, political, and epistemological significance,

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: David Zwirner Gallery Archive

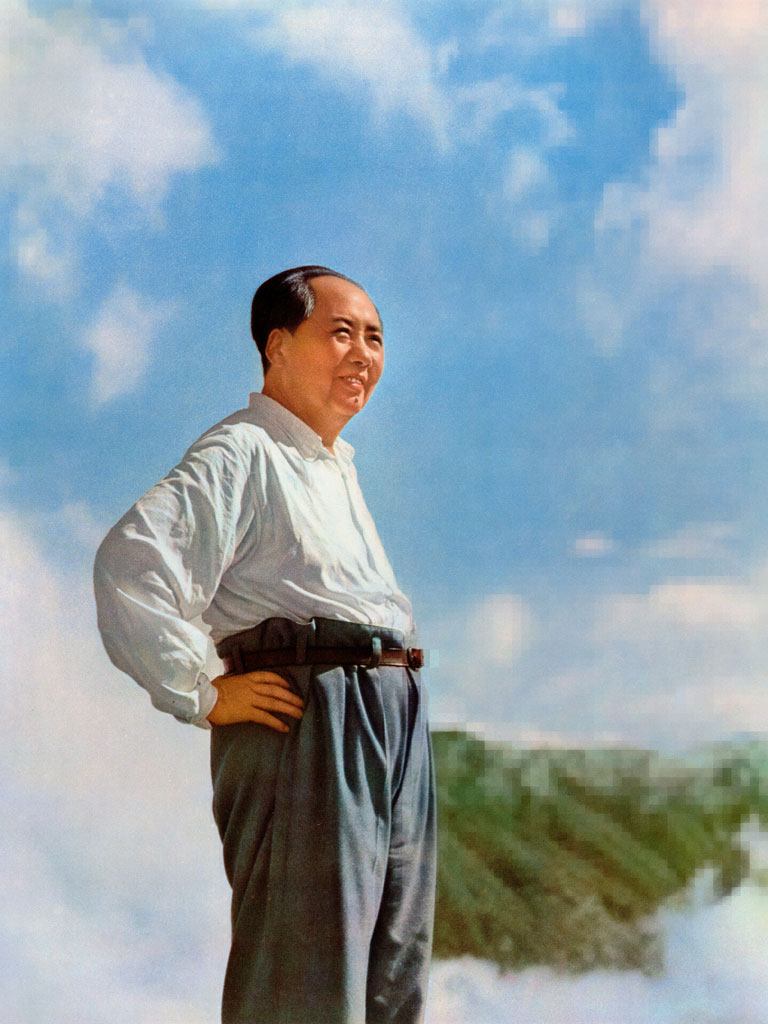

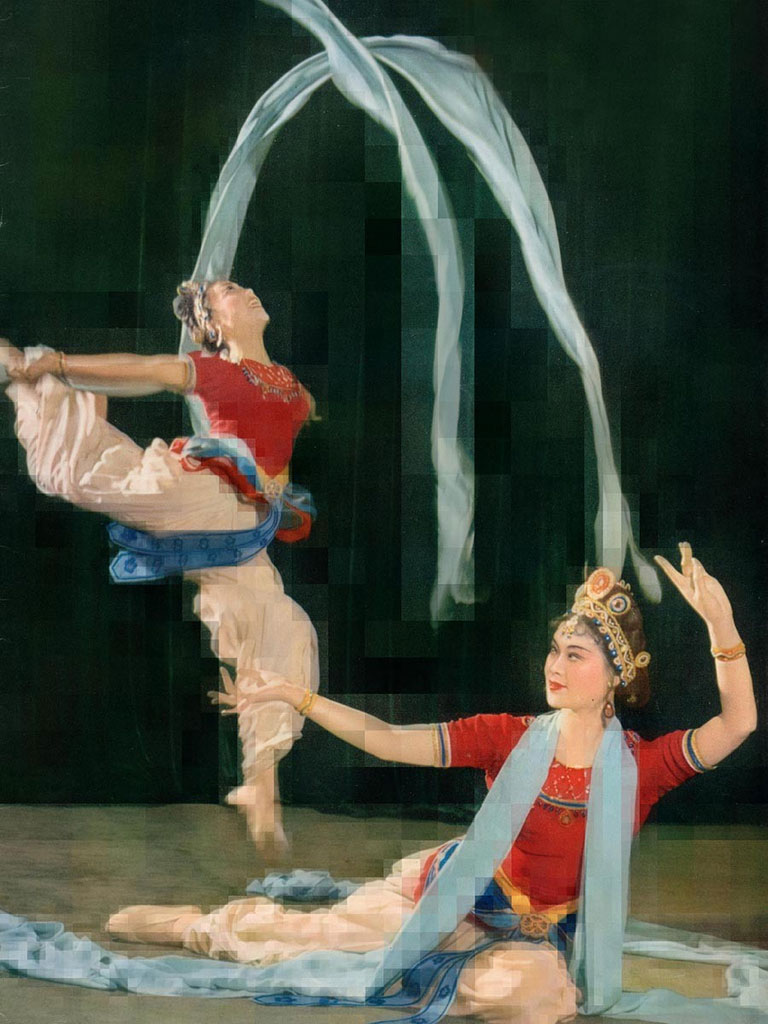

In the early 2000s, Ruff came across a coffee table book on Mao Zedong that grandly valorized the Chinese leader’s life and achievements, and became interested in Mao not only as a political figure but also as a cultural reference point, depicted by a range of Western artists (most notably, Andy Warhol. Ruff subsequently purchased a group of La Chine magazines) the French iteration of a periodical that the Chinese Communist Party produced specifically for Europe and distributed in several Western languages from the late 1950s through the 1970s as a means of demonstrating the advantages of Communism. Ruminating over this material for several years, the artist considered China’s unique position in relationship to the West as a country that is technologically advanced but simultaneously ideologically regressive, and began to devise a way to embody this dichotomy within a single image. To create the resulting works, Ruff begins with imagery scanned from these publications depicting smiling soldiers, scenic views, ceremonial gatherings, and Chairman Mao himself, among other subjects, enlarging them considerably to reveal the halftone dots created by the offset printing process. He then duplicates the image and converts the offset halftone of the duplicates into a large pixel structure. As a next step he places the new images, which have a digital image structure, as a second or third layer over the original scan, and then selectively removes parts of the second or third level. The resulting new image thus has both the halftone of the “analog” offset printing and the “digital” structure of the pixel image—at once laying bare both twentieth- and twenty-first-century techniques for the creation of propaganda images. The title of the series is a tribute to the French Icelandic painter Erró whose “Tableaux Chinois” paintings from the 1970s utilized a Pop art idiom to depict figures from Communist China visiting global landmarks, combining propaganda imagery with everyday imagery.

In his artistic treatment of this historical material, the analog and digital spheres overlap; and in this visible overlap, Ruff combines the image of today’s highly digitalized China with the Chinese understanding of the state in the 1960s and its manipulative pictorial politics. The works in the series “Zeitungsfotos” were created between 1990 and 1991 as color prints framed with passe-partouts. They are based on a collection of images which the artist cut out of German-language daily and weekly newspapers between 1981 and 1991. The selected motifs from politics, business, sports, culture, science, technology, history, or contemporary events reflect in their entirety the collective pictorial world of a particular generation. The artist had the selected images reproduced without the explanatory captions and printed in double column width. In this way, he questions the informational value of the photographs and directs our attention to the rasterization of newspaper print. Black-and-white press photographs from the 1930s to the 1980s, which were taken primarily from American newspaper and magazine archives, are the source material for the “press++” series. Thomas Ruff has been working on this series since 2015, scanning the front and back sides of the archive images and combining the two sides so that the partially edited photograph of the front side is fused with all the texts, remarks, and traces of use on the back side. When printed in large format, the often disrespectful handling of this type of photography becomes visible. His large-format photos of the series “nudes” draw on motifs and forms of presentation of thumb nail galleries (compilations of small images as previews) with pornographic images as they can be found on the Internet. By making the coarse pixel structure of the Internet images of the turn of the millennium into a pictorial principle, he thematizes the technical conditions of the photographic images in his works. With the series “jpeg” , he continued these investigations and connected his selection of media images with the question of a collective memory for images and contemporary history. Images distributed worldwide through the Internet, as well as scanned postcards and illustrations from photobooks, are the visual starting point of the “jpg” series, on which Thomas Ruff has been working since 2004. In it, he focuses attention on a feature that determines all images compressed in JPEG format and becomes visible at high magnification. By intensifying the pixel structure and simultaneously enlarging the overall image, he creates a new image that resembles a geometric color pattern when viewed closely but becomes a photographic image when viewed from a greater distance. Here, Ruff uses ideas from the painting of late Impressionism and combines these with the digital possibilities of the twenty-first century. By using the entire range of images published globally and simultaneously discussed in recent decades, he allows the series to become almost a visual lexicon of media imagery and a reflection of its characteristics determined by the medium. Fascinated by photograms of the 1920s, Thomas Ruff decided to explore the genre and develop a contemporary version of these camera-less photographs in the “Fotogramme” series. Beyond the limitations of analog photograms, the artist has been developing his versions of photograms since 2012, using a virtual darkroom to simulate a direct exposure of objects on photosensitive paper. With this, he was able to place objects (lenses, rods, spirals, paper strips, spheres, and other objects) generated with the help of a 3D program on or over a digital paper, correct their position, and in some cases expose them to colored light. He could thus control the projection of the objects on the background in virtual space and print the image calculated by the computer in the size he wanted. In this way, he succeeded in capturing the concepts and aesthetics of the pioneers of “kameralosen Fotografie” in the 1910s and 1920s, generating images with light and transporting them into the twenty-first century using a technique appropriate to his own time.

In 2014, Thomas Ruff began to work more intensively on the visual appearance of the source material of analog photography, the “negativ”. In order to make its photographic reality and pictorial quality visible, he transformed historical photographs into “digital negatives” In the process, not only the light-dark distribution in the image changed; the brownish hue of the photographs printed on albumin paper also became a cool, artificial blue tone. The aim of the processing was to highlight the photographic “negative”, which, in analog photography, was never the object of observation, but always a means to an end. In this series, it is treated as an “original” worth viewing, from which a photographic print is made, and which is in danger of disappearing completely due to digital photography. The series covers the entire spectrum of historical black-and-white photography and is divided into different subgroups. On display are the series “neg◊lapresmidi” and “neg◊marey”. During his research on photographs from outer space, Thomas Ruff came across photographs of Mars. These were taken by a camera within a probe sent into outer space by NASA in August 2005 and has been sending detailed images of the surface of the planet Mars to Earth since March 2006. The images are intended to enable scientists to obtain more precise knowledge of the surface, atmosphere, and water distribution of Mars. For his series, “ma.r.s.” created between 2010 and 2014, the artist processed these very naturalistic yet strange images in several steps; among other things, he transformed the black-and-white transmitted images, which were photographed vertically top-down, into an oblique view and then colored them so that the surface of the distant planet appears accessible and almost familiar. The works of the subgroup “3D-ma.r.s.” illustrated here are photographs of the surface of Mars which were produced using the so-called anaglyph process. When viewed with red-green glasses, a spatial, three-dimensional image is created in the brain. Since the early days of photography, monochrome and multicolor retouching has been used or images have been colored. Thomas Ruff explores one possibility in his series “Retusche” (Retouching) as a form of embellishment and an approach to an ideal. His machines are heightened and isolated by coloring the motifs with typical colors of industrial production. For the work groups “m.n.o.p.” and “w.g.l.”, the artist partially colored photos of exhibition situations in order to highlight forms of presentation in museums and design intentions in exhibition practice.

Photo: Thomas Ruff, from the series “tableau chinois”, 2019, C-Print, © Thomas Ruff/VG Bild Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Info: David Zwirner Gallery, 108 rue Vieille du Temple, Paris, Duration: 14/1-6/3/2021, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-19:00 (Booking Required), www.davidzwirner.com