ART CITIES:Los Angeles-Laurie Anderson

![]() Laurie Anderson is one of today’s multimedia artists, known for her achievements as a visual artist, composer, poet, photographer, filmmaker, vocalist, and instrumentalist, and her innate ability to meld her dynamic practices into new and vibrant forms. Her seemingly boundless oeuvre includes the creation of books, albums, and performances that incorporate film, slides, recorded audio, live music, and spoken word.

Laurie Anderson is one of today’s multimedia artists, known for her achievements as a visual artist, composer, poet, photographer, filmmaker, vocalist, and instrumentalist, and her innate ability to meld her dynamic practices into new and vibrant forms. Her seemingly boundless oeuvre includes the creation of books, albums, and performances that incorporate film, slides, recorded audio, live music, and spoken word.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: MASS MOCA Archive

In her solo exhibition Laurie Anderson invites viewers to explore a multi-functional constellation of galleries and installations including a working studio, audio archive, exhibition venue, and a virtual reality environment for experiences she co-created with Hsin-Chien Huang. Taken together, the exhibition highlights both Anderson’s creative process and some of her most unforgettable works. In 1974, two years after graduating from Columbia University with her MFA, Anderson developed her first multimedia performance: “As:If”. In the performance Anderson sat in a gallery wearing all white with ice skates embedded in frozen blocks of water, she played music, and she told stories about her midwestern upbringing, her Baptist grandmother, language, and the fickle nature of memory. This was the first time she put a small speaker directly into her mouth to alter her voice (a tactic she continues to use through vocal modulators). A year later Anderson performed “Duets on Ice” on the streets of Genoa, Italy. Again in all white with skates embedded in ice, she stood on the street and played a duet with her own violin, while telling stories to passersby. The performance ended when the ice melted. This duet was made possible through the invention of a self-playing violin. Anderson fit the inside of the instrument with a playback device so that it could play while she moved the bow across the violin, allowing her to layer sound, story, and performance. These early performances and instrument modifications form the backbone of Anderson’s work even today. A habitual innovator, she has created books, albums, and performances that incorporate film, slides, recorded audio, live music, and spoken word. She was pioneering in her development of the “Tape-Bow Violin” (1974), a violin in which she replaced a traditional bow with magnetic audiotape, and fit the bridge of the instrument with a tape head for playback; the “Viophonograph” (1976), a battery-powered turntable set into a violin with a bow containing a needle; a digital violin (1985), a neon violin and bow (1982, 1985), and “The Handphone Table” (1978), which transforms the human body into a listening device. “The Handphone Table” (began when Anderson was using an electric typewriter, and, in a moment of frustration, put her head in her hands, elbows on the table. She then heard the sound of humming transferred through the wooden table, up through her arms, into her ears.

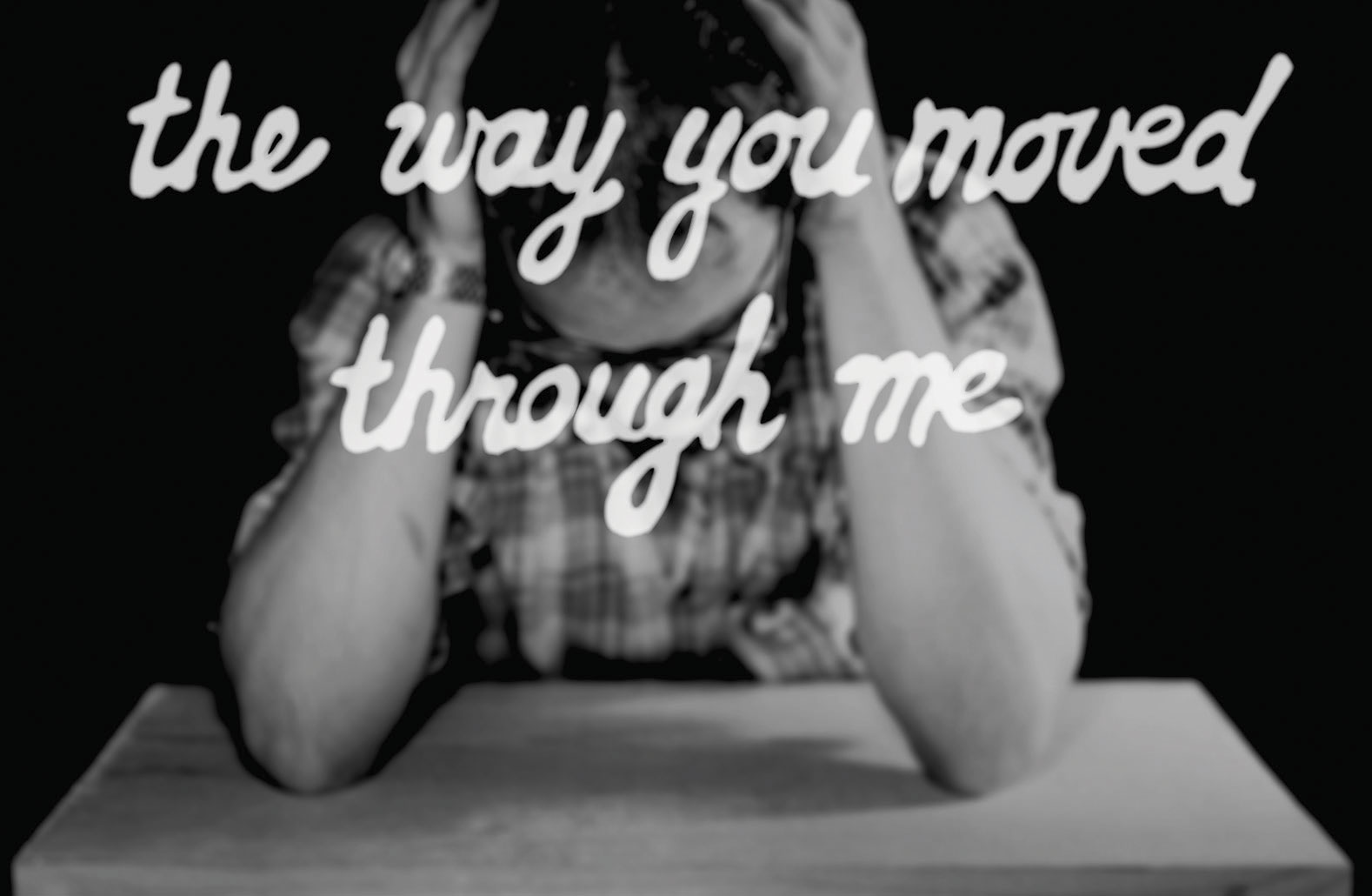

As with the “Tape-Bow” Anderson uses many of these innovations in her multimedia performances. In 1983 she premiered the eight-hour work “United States” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Divided into four parts (transportation, politics, money, and love) the work was a collective portrait of a country. Illuminated on stage by slides and projected films, Anderson told shifting stories illustrating the intertwined politics, power, and humanity of this country, painting an almost impossible picture of an impossibly complex place. Some vignettes were deadpan, such as the story of American farmers selling their silos to the federal government for the storage of nuclear missile heads, while others spoke directly to us. Anderson continues to create ambitious performances such as “Songs and Stories from Moby Dick” (1999), a postmodern opera about authority, madness, and meaning of life; or “Delusion” (2010), which explores “the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, our families, our country, and the world, and the porousborder between history and myth. Across all of these performances and her numerous albums, Anderson continuously experiments with new media. For example, “Moby Dick” premiered the “Talking Stick” a six-foot baton with a MIDI controller allowing her to access any recorded sound; or vocal filters, such as those that deepen her voice to a masculine register. By refocusing voice, language, and narrative, Anderson reminds us that the stories we tell are beleaguered by the failings of memory and the effects of time. Since her days in art school—when she made sculptures from newspapers—stories, words, and the dissemination of language have always been her end game. With her installations, however, Anderson has the power to use herself as a storyteller, to implicate her audience, or collaborate with remote participants. “At the Shrink’s” (1975), her first foray into creating fake holograms, shifted her presence from in-person to projected. The technique involved making a clay sculpture of a miniaturized Anderson sitting in a chair, onto which she projected an image of herself telling a story about visiting the psychiatrist. As the video covers the three-dimensional surface, it makes you feel like you are in the room with a small-scale Anderson, and that she is telling her story to you alone. Furthering these experiments in remote embodiment, Anderson’s most recent investigations involve virtual reality (VR). Unlike most experiments in VR that are situated within gaming, Anderson endeavors to bring us into her world, to use this augmented state to tell stories interactively in a state of total immersion. The first of two VR works at MASS MoCA references a plane crash that Anderson survived in the 1970s. She has told this story through songs such as “From the Air” from “Big Science” (1982). She sings, “Good evening. This is your captain. We are about to attempt a crash landing…Put your hands over your eyes. Jump out of the plane. There is no pilot. You are not alone.” In “Aloft” (2017), the piece begins with you sitting inside an airplane, which slowly dissolves around you until you are left hovering in space. There is no panic, no plummet, just objects drifting by that you can grab and hold close. Each object in your grasp tells a story, and Anderson’s voice, as our pilot and guide, soothes any fear.

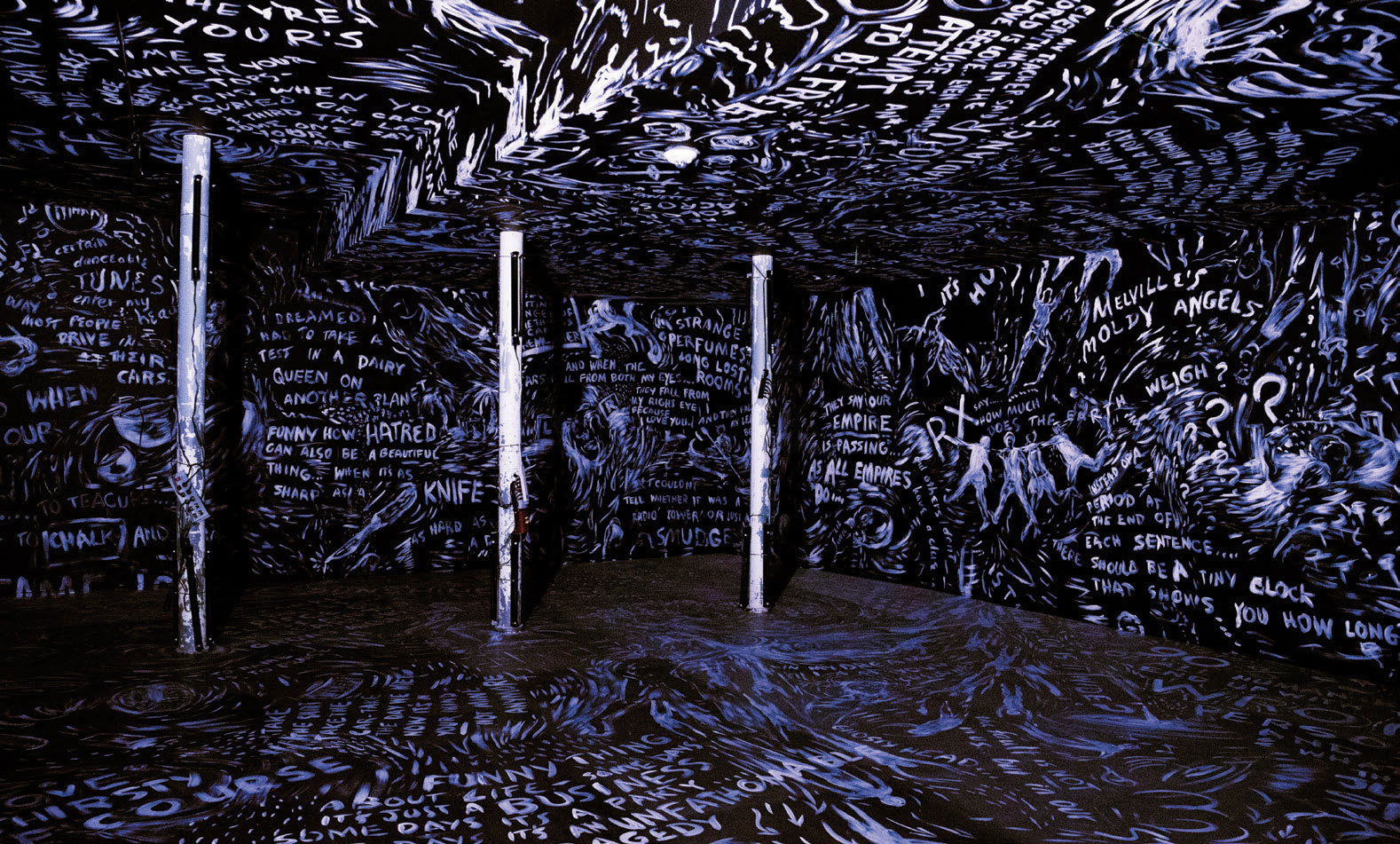

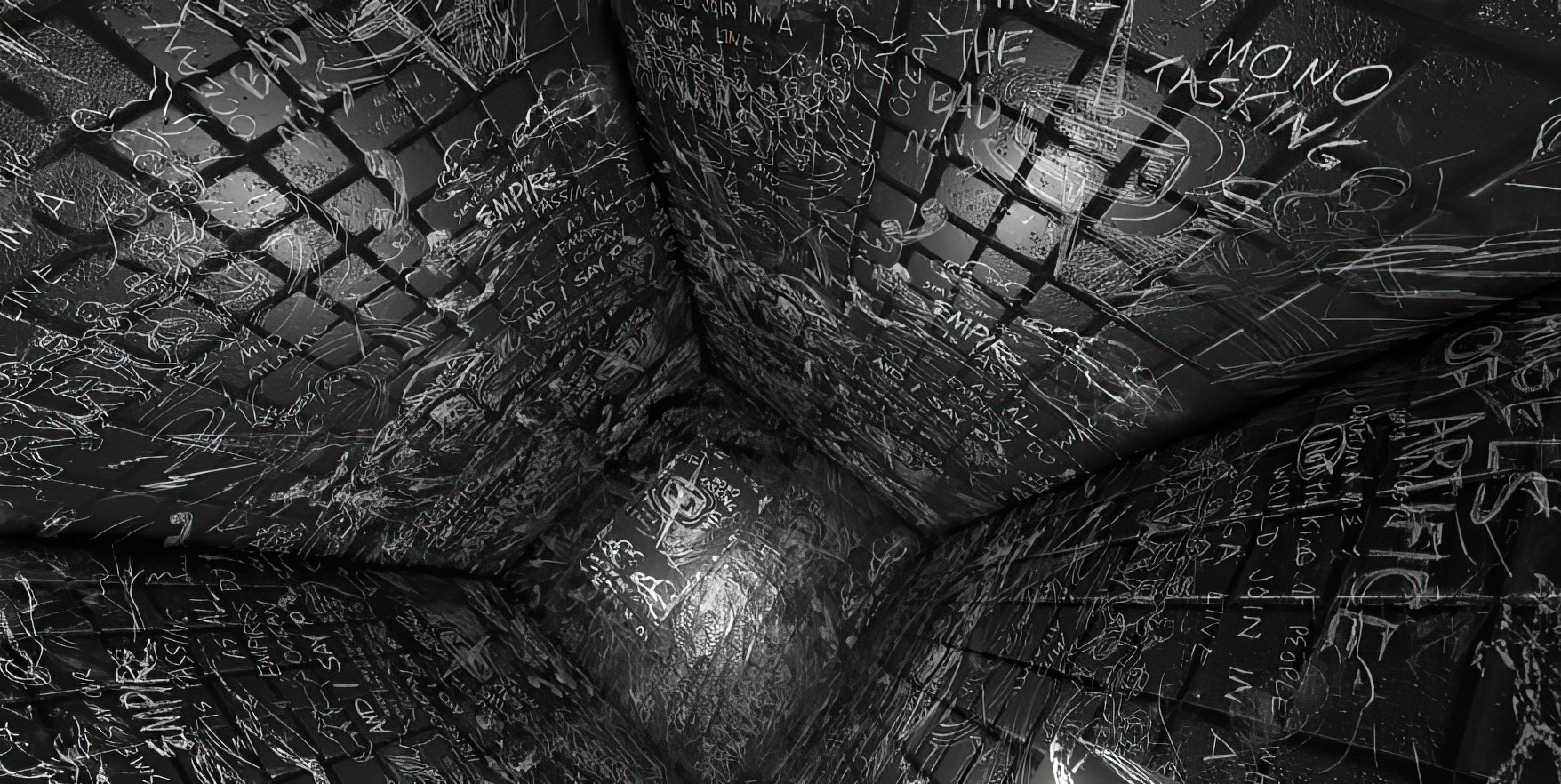

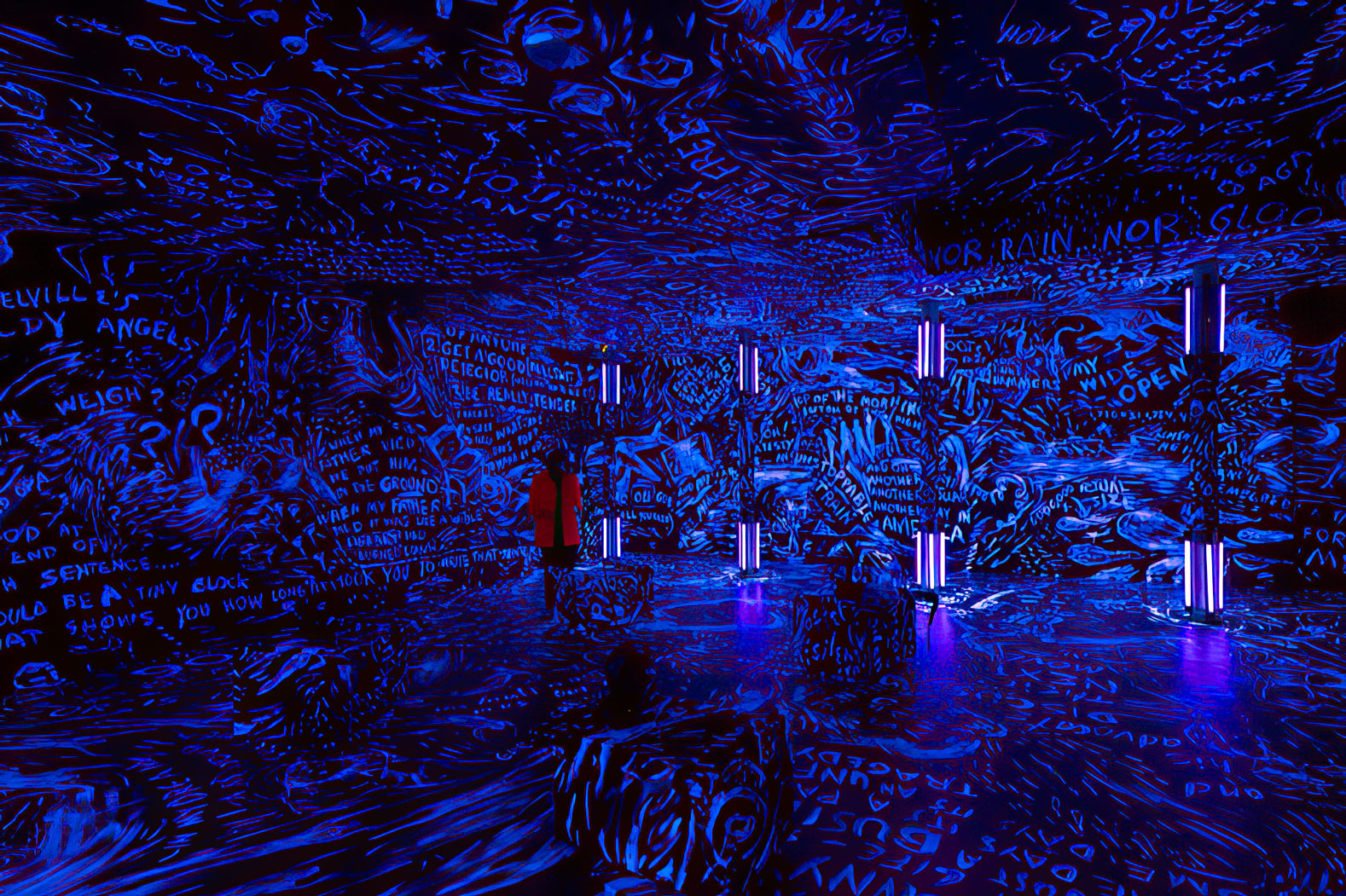

The “Chalkroom” (2017), a second VR work, harkens back to Anderson’s 1996 installation for the Hugo Boss Prize at the Guggenheim Museum in SoHo, New York. The early installation comprised a series of rooms—walls covered with drawings and text in chalk—surrounding an assortment of interactive storytelling devices. At MASS MoCA, Anderson takes this to the next level. Once again she covers the walls, ceiling, and floor with language and gestural drawings that glow in the black-lit space. She and her team mapped the actual room so that when you don the VR headset you begin in a familiar place. But soon you find yourself gliding through a labyrinth of rooms, as bits of text fly by and stories ring out in your ears. With these VR works Anderson is experimenting with a whole new way to talk to us, while also allowing us to shape our own experiences. While Anderson frequently uses technology, she tells her stories in other ways as well. In 2011, the death of her dog, Lolabelle, triggered a series of works including her 2015 film “Heart of a Dog”, which explored her childhood and the deaths of her mother and Lolabelle. Anderson, a practicing Buddhist, imagined her dog in the Bardo (in which, according to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, all living things must spend 49 days in preparation for reincarnation). Anderson’s large-scale charcoal drawings of Lolabelle’s journey are vast and gestural, open in a way that makes you feel like you can leap inside of them, like no-tech virtual reality. We stand with Lolabelle witnessing both chaos and calm. “Lolabelle in the Bardo, April 18” is a vortex of energy, the dog hardly present. In the other hand, “Lolabelle in the Bardo, May 5”, functions like a stock of memories, depicting multiple versions of the dog including one of Lolabelle playing the keyboard (a task she was taught late in life to combat boredom as her eyesight failed). In each drawing Anderson includes a Tibetan prayer wheel, always spinning like a dervish, symbolizing the cyclical nature of life and the stories we tell each other.

Photo: Laurie Anderson, Handphone Table, 1978, In “Handphone Table” visitors are invited to perceive sounds through the bones in their elbows, © Laurie Anderson, Courtesy the artist and MASS MOCA

Info: MASS MOCA, 1040 MASS MoCA WAY North Adams, Duration: 29/5/2019-31/12/2021, Days & Hours: Thu-Mon 10:00-17:00 (booking required), https://massmoca.org

Right: Laurie Anderson, The Chalkroom, 2017, Virtual reality installation with Hsin-Chien Huang, © Laurie Anderson, Courtesy the artist and MASS MOCA