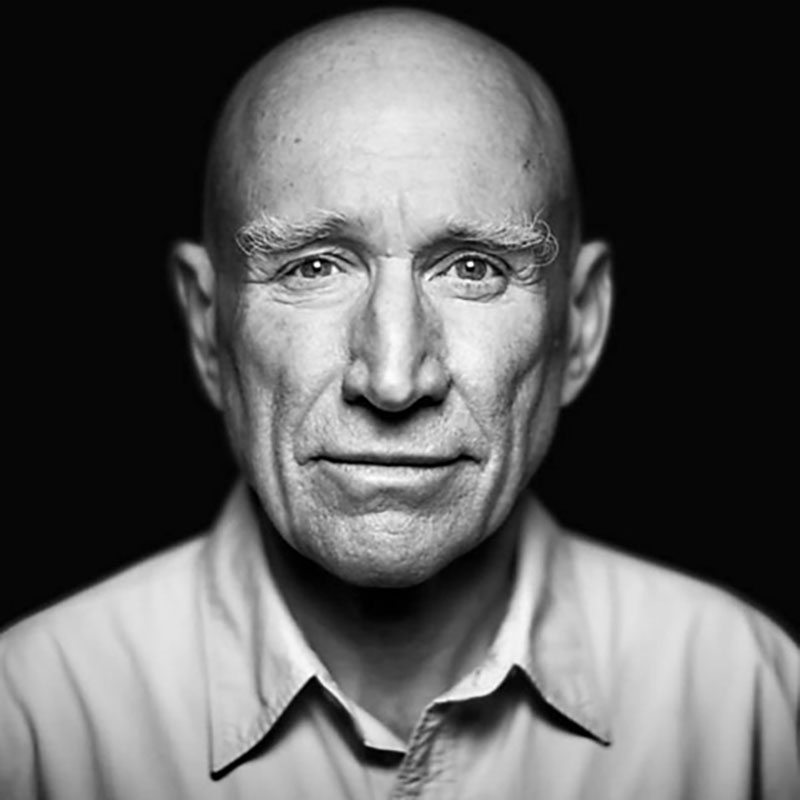

PORTFOLIO:Sebastião Salgado

Sebastião Salgado’s (8/2/1944- ) straightforward photographs portray individuals living in desperate economic circumstances. Because he insists on presenting his pictures in series, rather than individually, and because each work’s point of view refuses to separate subject from context, Salgado achieves a difficult task. His photographs impart the dignity and integrity of his subjects without forcing their heroism or implicitly soliciting pity, as many other photographs from the Third World do. Salgado’s photography communicates a subtle understanding of social and economic situations that is seldom available in other photographers’ representations of similar themes.

Sebastião Salgado’s (8/2/1944- ) straightforward photographs portray individuals living in desperate economic circumstances. Because he insists on presenting his pictures in series, rather than individually, and because each work’s point of view refuses to separate subject from context, Salgado achieves a difficult task. His photographs impart the dignity and integrity of his subjects without forcing their heroism or implicitly soliciting pity, as many other photographs from the Third World do. Salgado’s photography communicates a subtle understanding of social and economic situations that is seldom available in other photographers’ representations of similar themes.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Sebastião Salgado was born on a large cattle farm in Aimorés in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to a middle class family as the sixth of eight children. He has said that his childhood spent on the farm heavily influenced the expansiveness for which his photography is renowned. Salgado moved to a nearby city for school and then to Vitória and São Paulo to study economics. In 1967 he married Lélia Deluiz Wanick who went on to play an integral role in the development of his photographic practice. He considers his work the product of their partnership, and Lélia to be the visionary and guiding force in the planning and execution of his projects. They have two sons and one grandson. Salgado began his career as an economist working for the secretary of finance to the state of São Paulo before moving to Paris to undertake a doctorate. This move was largely the result of his participation in the student protests against Brazil’s military dictatorship that led to the revocation of his Brazilian passport. Exiled for ten years, his passport was only regained after a process of litigation, but the family decided to remain in Europe, partly to ensure the care of one of their sons who was born with Downs syndrome. Salgado started working for the International Coffee Organisation at this time and travelled extensively to Africa for the World Bank. Salgado began photographing in the early 1970s when Lélia bought a camera to use whilst studying architecture. In 1973 he gave up his career as an economist as photography made “a total invasion” of his life. After working for the Sygma and Gamma photo agencies, in 1979 he joined Magnum, that had been founded by the four fathers of modern photojournalism (Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David Seymour). He cemented his reputation as a photojournalist, however, when he captured the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in March 1981. Leaving Magnum in 1994, Salgado set up the photo agency, Amazones Images, in partnership with Lélia to promote his photography. In 1999 the couple also founded the Instituto Terra, a non-profit organisation established to conserve the Atlantic rainforest that surrounded his family home. Taking over the cattle ranch that had been owned by his father, Sebastião and Lélia set about undoing the devastation caused by deforestation and erosion and recreated a forest with the species that had once flourished there.

Sebastião Salgado was born on a large cattle farm in Aimorés in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to a middle class family as the sixth of eight children. He has said that his childhood spent on the farm heavily influenced the expansiveness for which his photography is renowned. Salgado moved to a nearby city for school and then to Vitória and São Paulo to study economics. In 1967 he married Lélia Deluiz Wanick who went on to play an integral role in the development of his photographic practice. He considers his work the product of their partnership, and Lélia to be the visionary and guiding force in the planning and execution of his projects. They have two sons and one grandson. Salgado began his career as an economist working for the secretary of finance to the state of São Paulo before moving to Paris to undertake a doctorate. This move was largely the result of his participation in the student protests against Brazil’s military dictatorship that led to the revocation of his Brazilian passport. Exiled for ten years, his passport was only regained after a process of litigation, but the family decided to remain in Europe, partly to ensure the care of one of their sons who was born with Downs syndrome. Salgado started working for the International Coffee Organisation at this time and travelled extensively to Africa for the World Bank. Salgado began photographing in the early 1970s when Lélia bought a camera to use whilst studying architecture. In 1973 he gave up his career as an economist as photography made “a total invasion” of his life. After working for the Sygma and Gamma photo agencies, in 1979 he joined Magnum, that had been founded by the four fathers of modern photojournalism (Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David Seymour). He cemented his reputation as a photojournalist, however, when he captured the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in March 1981. Leaving Magnum in 1994, Salgado set up the photo agency, Amazones Images, in partnership with Lélia to promote his photography. In 1999 the couple also founded the Instituto Terra, a non-profit organisation established to conserve the Atlantic rainforest that surrounded his family home. Taking over the cattle ranch that had been owned by his father, Sebastião and Lélia set about undoing the devastation caused by deforestation and erosion and recreated a forest with the species that had once flourished there.

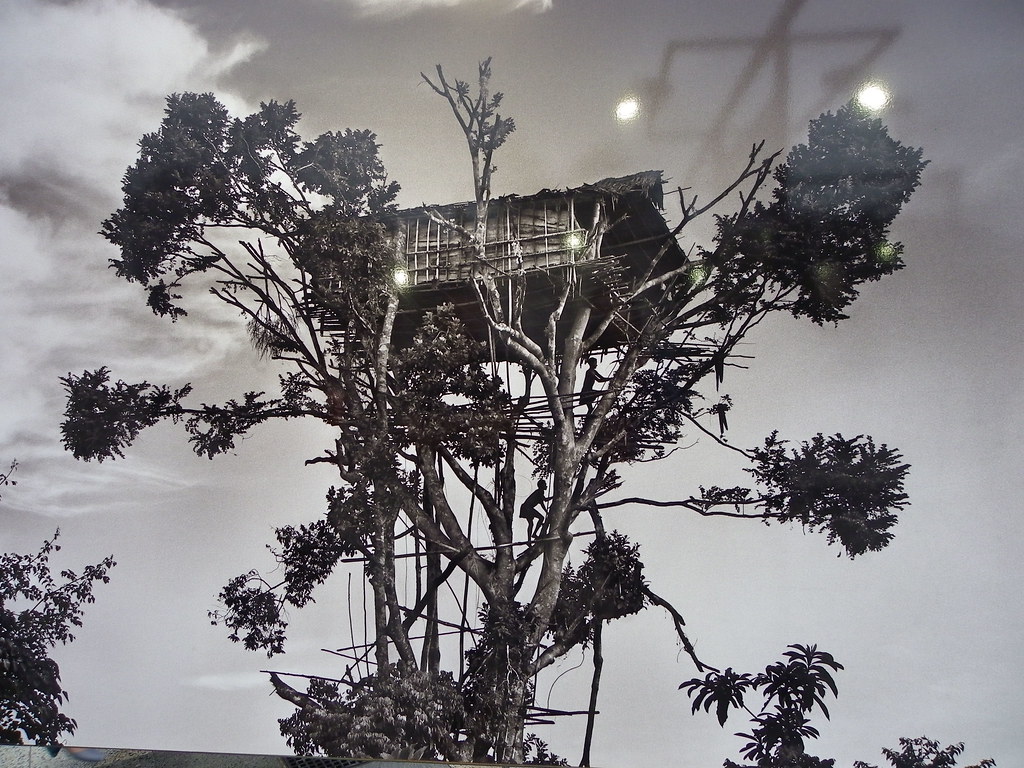

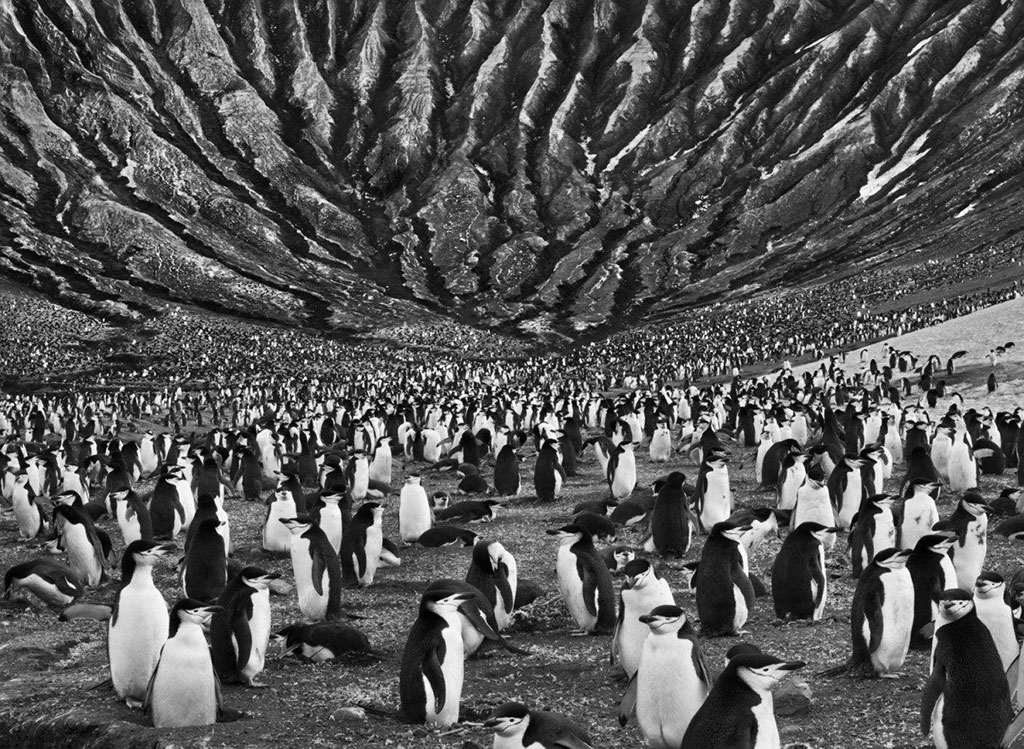

He won the City of Paris/Kodak Award for his first photographic book, “Other Americas” which recorded the everyday lives of Latin American peasants. This was followed by Sahel: Man in Distress (1986), a book on the 1984–85 famine in the Sahel region of Africa, and “An Uncertain Grace” (1990), which included a remarkable group of photographs of mud-covered workers at the Serra Pelada gold mine in Brazil. In order to understand the communities and habitats he photographs, Salgado undertakes prolonged projects, or “photo-essays”, that present huge, thrilling dramas of clashing geographical, social and cultural structures. His earlier projects “Migration and Workers” centre on the trials of humanity across the globe, taking seven and six years respectively. Consumerism is constantly impinging on the wilderness in these photographs as the ancient and modern come into terrifying proximity. Some of Salgado’s most famous images were taken at the Serra Pelada gold mine in Brazil where he immortalised scenes of medieval horror as tens of thousands of men worked in appalling conditions. Despite the foreboding shadow cast by humanity’s propulsion towards self-destruction, community is constantly at the centre of Salgado’s vision. Displaced, degraded and corrupted, humanity can always be ennobled through the return to community. He won the City of Paris/Kodak Award for his first photographic book, “Other Americas” which recorded the everyday lives of Latin American peasants. This was followed by “Sahel: Man in Distress” (1986), a book on the 1984–85 famine in the Sahel region of Africa, and “An Uncertain Grace” (1990), which included a remarkable group of photographs of mud-covered workers at the Serra Pelada gold mine in Brazil. In the 1990s Salgado recorded the displacement of people in more than 35 countries, and his photographs from this period were collected in “Migrations: Humanity in Transition” (2000). Many of his African photographs were gathered in “Africa” (2007) After photographing brutality and violence across the globe, Salgado’s photo-essay “Genesis” marked a rekindling of faith in the partnership of humanity and nature. Completed in 2013, the eight-year project is awesome in the truest sense of the word. “Genesis” is about returning to origins – finding nature in its pure, pristine state. It takes us on a journey to the remotest regions of the planet to see five tonne elephant seals in South Georgia, people of the Dinka tribe herding cattle, thousands of penguins on Zavodovski Island and the Nenets of northern Siberia crossing the ice into the Arctic Circle. As Salgado has said, “Genesis” is a “mosaic presented by nature itself”, but it is not just a romantic contemplation of the sublime, instead, it opens up a discussion about what we have done to the planet and what we must now do to protect it. More so than any other contemporary photographer, Salgado has come to typify the genre of fine art photojournalism. Renowned for his highly skilled tonality, the chiaroscuro effect of his dramatic black and white images has contributed to the repositioning of photography as “high art”. This success undoubtedly issues from his political insight and distinctive aesthetic that renders the world both beautiful and humbling. It is this combination of political and aesthetic force that makes it impossible not to respond to Salgado’s photography with thought and comment.