ART-PRESENTATION: Image Wars-The Power of Images

In the course of digitalization, more meaning has been attributed to the image than to the written or spoken word. Contemporary culture can be described as visually oriented: Our images become our opinions, our actions, our stories. What we see today will be our memory tomorrow. Images of violence have an especially strong effect. This power of images demands a rigorous and broad question of reality, which is always constructed.

In the course of digitalization, more meaning has been attributed to the image than to the written or spoken word. Contemporary culture can be described as visually oriented: Our images become our opinions, our actions, our stories. What we see today will be our memory tomorrow. Images of violence have an especially strong effect. This power of images demands a rigorous and broad question of reality, which is always constructed.

By Efi Michalarou

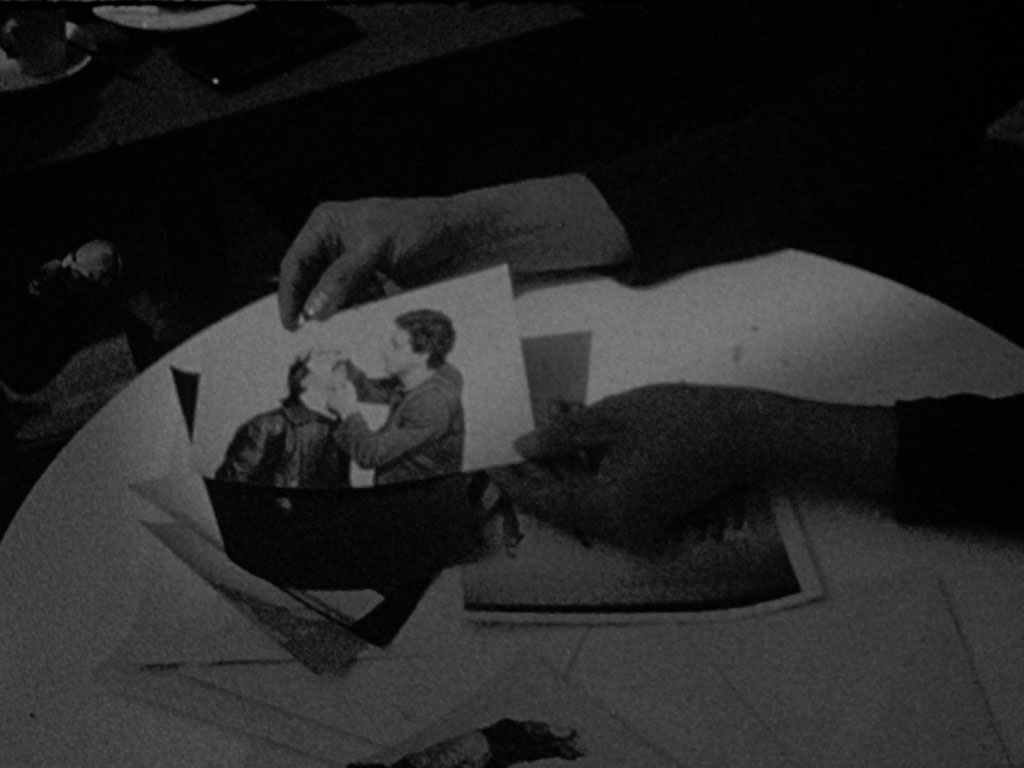

Photo: Künstlerhaus Archive

The exhibition “Image Wars: The Power of Images” seeks to animate such “disobedient seeing” and to that end brings together six works of video art that illuminate from different perspectives images of violence and violence in images. In the exhibition are on presentation works by: Kader Attia, Cana Bilir-Meier, Melvin Moti, Rabih Mroué, Mario Pfeifer, and Marlies Pöschl that take up the mechanisms between the contemporary reception of images and the culture of memory. Since the electronic revolution, people find themselves confronted with a quantity and frequency of visual signs never seen before. New cultural techniques and technologies accordingly create an increasing expectation of visibility and shape the ability to think and hence also to remember. In that context, Marlies Pöschl engages in “سینمای کریستال / Cinema Cristal” (2017) with the mutability of the collective reception of moving images using the example of the transformed role of cinema in Tehran after the Iranian Revolution and in the process identifies an aesthetic and social space of memory. The short film “This Makes me Want to Predict the Past” (2019) by Cana Bilir-Meier in turn, illustrates the multilayered, subjective superimpositions in the tension between the image of political events and individual memory. Her work dovetails the racially motivated assassination in Munich’s Olympia shopping center of 2016 with archival photographs of the play “Düşler Ülkesi” (1982). Visual memory of violent images cannot be understood without taking into account our reception of violence, whether captured in media or actually practiced. Torn between repulsive and attractive forces, our looking at depictions of suffering constantly alternatives between looking at and looking away. Melvin Moti’s film “Cosmism” (2015) is a commentary on the visual representation of violence in documentations of historical events. The work juxtaposes human brutality, destruction, and panic with the natural energy and aesthetic of nature by combining a cinematic reenactment of Mary Stuart’s beheading with found footage of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, in New York, and visual materials from NASA. Today, inspired by the possibilities of the digital, everyone produces a surplus of visual material. Reporting and information are no longer solely the work of the mass media but occur via social networks as well. As a result, the violent potential of photographs is involved to a previously unknown degree in the legitimation of political stances and actions. “The Pixelated Revolution” (2019) by Rabih Mroué address the use of mobile telephones during the Syrian Revolution and the effect of the at times gruesome amateur photographs from the crisis region that were shared via virtual and viral communication platforms. This aspect is also reflected in the video installation “Again / Noch einmal” (2019). The artist Mario Pfeifer reconstructs, based in press reporting following a cell phone video that was disseminated online, the case of Schabas Al-Aziz, who had fled Iraq and, after a conflict with a supermarket cashier In Arnsdorf, Saxony, was tied to a tree. This tragic story of xenophobia, civil courage, and vigilante justice illustrates with multiple perspectives the legal, political, and social impact with which today’s economy of attention is controlled by visual material. Systematic visual politics and framing, staging, and censorship are the consequences and in turn lead to images being employed as weapons in the metaphorical sense that can shape opinions and mobilize the crowds. Sometimes we feel pursued by our remembered images. Imagining what we have experienced is a daily part of psychological hygiene and after societal or individual traumatic experience can take on burdensome and even compulsive forms. This level of meaning of visual representation is also taken up in the exhibition. For example, “Reflecting Memory” (2016) by Kader Attia reflects on the symptom of phantom pain after amputations. The images of the protagonists seeing themselves in the mirror convey the diversity of individual and collective memory and demonstrate not least that peace and reconciliation always also mean forgetting.

Info: Curator: Jana Franze, Künstlerhaus, Halle für Kunst & Medien (KM– Graz), Burgring 2, Graz, Duration: 4/7-8/10/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.km-k.at