ART CITIES:Berlin-Recurrence

All the artworks of the group exhibition “Recurrence“ at Zilberman Gallery in Berlin make references to the 19th Century, a period when science, economy and technology developed dramatically but at the same time Romanticism constituted an alternative world to industrialisation and technological advances. Love and longing, and devotion to nature are the romanticist’s emotional fuel and create an environment of comfort for the individual in a rapidly changing world.

All the artworks of the group exhibition “Recurrence“ at Zilberman Gallery in Berlin make references to the 19th Century, a period when science, economy and technology developed dramatically but at the same time Romanticism constituted an alternative world to industrialisation and technological advances. Love and longing, and devotion to nature are the romanticist’s emotional fuel and create an environment of comfort for the individual in a rapidly changing world.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Zilberman Gallery Archive

Today, in another era of intrusive change, humans’ relationship to nature is again being looked at closely, but because the contemporary conditions have changed the examination process is also taking place differently. The exhibited works strike a balance between historical research and the attempt to discover a narrative style between narration and abstraction. Recurrence of the same with minor variations, sequences of similar objects as well as pattern-like systems of elements are characteristics not only of the paintings and objects but also of the videos – where we observe the reduction of content and the rhythmic return of similar sequences. A modest use of color up to strict black and white, long shots, silence and slow filmic movements imbue the exhibition with a contemplative character. Observers are given the time and space to explore the principle of similarity and difference in things as well as in historical developments. In troubled times, concentrating on what is constant and recurrent can provide an unexpected point of reference and thereby contribute to our understanding of future paradigms.

Simon Wachsmuth researches the blind spots and unexpected epilogues in the grand narratives of history and art history. His works often use archival materials, which stand in dialogue with a vocabulary of minimalistic forms. Monuments and documents, both as motif and notion, reappear in his oeuvre as preserving material carriers capable of becoming integral parts of individual and collective memory. Wachsmuth is interested in these materialisations of memory: by dealing with the cultural (re)constructions of history, he questions the relationship between material traces, museological representations, and forms of their present employment. Wachsmuths’ installations might be compared to loosely knitted nets, in which he recaptures the materials dispersed by the migration of forms and images over time and space. Simon Wachsmuth’s work level, an arrangement of aluminium poles painted black and white, is the opening piece in “Recurrence“. On the one hand, the poles make us think of real objects, such as yardsticks, limitation rods, speers, oversized Mikado sticks or even hiking poles; on the other hand, they reference the language of geometric abstraction. Similar poles could be seen in Heinrich Reinhold’s landscape painting “Künstler durchqueren die österreichischen Alpen” which was shown in an exhibition at Kunstraum Dornbirn. In a work reminiscent of the Biedermeier period, Reinhold painted himself and other artists with long hiking poles on the search for motifs for their realistic landscape paintings. Wachsmuth’s preoccupation is to show that perception has no longer been a mimetic depiction of reality for some time now, but rather a subjective construction of signs that is subject to many influences. In Wachsmuth’s interpretation, the only thing remaining from Reinhold’s picture, which for the artist is also a reflection on the painting activity itself, is the means by which each perceiver – artist or recipient – sets forth, i.e. the hiking pole. Wachsmuth’s level lead us to his black-and-white video “0,7”, which shows a series of ferry crossings across the Elbe in different weather conditions. The crossings are between Lower Saxony and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, formerly West and East Germany respectively, and the video is imbued with a specific political reference to opposing political systems. The landscape initially appears romantic but loses its allure through black-and-white fading that separates the crossings from each other and in doing so emphasises the dichotomous structure.

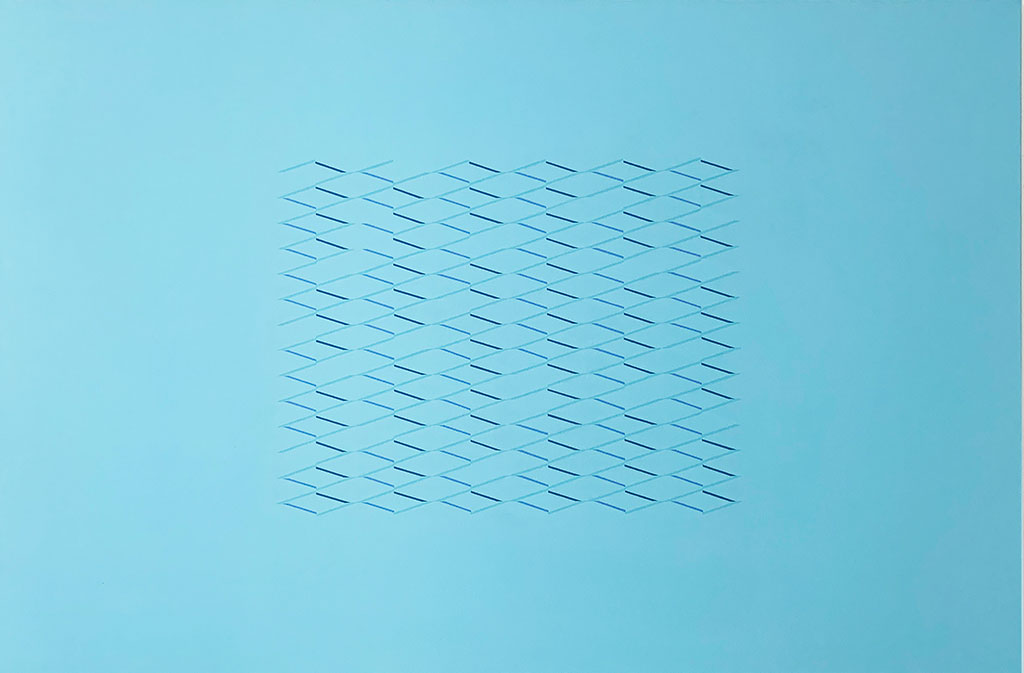

Isaac Chong Wai works across a range of media, including live performance, video, photography, and site-specific installation, and considers the interplay between the collective and the individual, the politics of time and space, and real and imagined futures. His works often engage with other performers with whom Chong performs, to allow for further interrogation of notions of the social and unified body. The blue paintings from his series “Line” appear abstract on first take. Against a background of opaque sky blue in various shades, we observe a regular pattern of rhombic, intersecting lines, reminiscent of op art. The lines are also in various tones of blue and the distribution of color is irregular. Some of the lines are omitted completely, leaving the structure incomplete. It is nearly impossible to recognise that these patterns have been drawn freehand, but they are inspired by objective perception occasioned by Chong’s research in a former prison in Weimar where the artist created a boat sculpture from a fence. In terms of form, his line paintings assume the same fence structure; thematically they depict the dichotomy of freedom and constraint. As the receiver, you search for inconsistencies in Chong’s grilles as closely as prisoners search for gaps in the bars of their prison cells.

Elmas Deniz is a concept-driven visual artist. Her works investigate the intersections and points of entanglement between economics and nature. The capitalism-led deterioration of nature, and our perception of it, as well as the related consumerist culture, are the central concepts in Deniz’s practice. She questions how the economic system continuously reshapes our perception through subtle but consistent manipulations. She sheds light on the illusional distribution of value. Deniz, further focuses on the human-nature relationship, the idea of nature throughout history and ecological concerns. Her works critically expose the faults of the system and occasionally propose alternative possibilities. Form-content interplay, the attempts to adapt the form to the concept, defines her choices. She hence consults a wide range of media, including installation, sculpture, video, drawing, and writings. Her videos focus on impressions of nature, in part supported with original sound, and contrast these with text that illustrates humans’ possessiveness towards the natural world. However, in contrast to nature films, which are currently being shown particularly regularly, Deniz makes only sparing use of the format: color is modest, movement is limited and the number of edits is small. The landscapes in Deniz’s videos are often free of human beings. It is only in the video “The Tree I Want to Buy” that a single person (the artist herself) is shown. The reduced treatment in this case consists of the viewing, feeling and evaluating of a 600-year-old tree in a way that is similar to the way a piece of real estate is viewed. The prospective purchaser’s thoughts appear on screen as ironic subtext, the striving to own taken ad absurdum. Deniz’s video “Human-less” plays out without any human presence whatsoever. A camera-carrying drone makes its way over a Caucasian valley before swivelling round and returning to its starting point. The valley has a flat, grassy floor like a steppe and a mountain stream meanders through it. Th/e steep rock faces on either side throw shadows over the valley, the lines of the shadows visible on the opposite valley wall. A higher mountain bathed in afternoon sun comes into view at the head of the valley. The camera is therefore moving towards the source of the water and the light, but it pivots around before reaching this point and returns to the starting point, in doing so creating a sense of frustration. Before the video ends, the still images are reviewed in sequence until the starting shot makes the time that has elapsed visible: the valley is now deeper in shadow than before. The video’s (only) text – “You are not a bird” – appears on screen and refers to humans’ keen use of technology to compensate for what they don’t possess naturally, e.g. having the drone’s eye observe the valley on their behalf. The arc of the orchestral music accompaniment, soaring harmoniously before descending again dissonantly, intensifies the emotional impression that humans are no match for the majesty of nature.

Info: Zilberman Gallery, Goethestraße 82, Berlin, Duration: 26/6-29/8/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-18:00, www.zilbermangallery.com