ART-PRESENTATION: Tetsumi Kudo-Cultivation

Tetsumi Kudo was a formative figure on the dynamic Japanese Avant-Garde scene and in the ‘anti-art’ currents in Tokyo at the end of the 1950s, until in 1962 he settled in Paris where he had his base for more than 20 years. Kudo’s interest in the ‘natural’ metamorphoses and transformations, of which we are always in the midst, is not only about relations between nature and mankind; it also has a critical, political angle to do with the power and value hierarchies of humanity and culture.

Tetsumi Kudo was a formative figure on the dynamic Japanese Avant-Garde scene and in the ‘anti-art’ currents in Tokyo at the end of the 1950s, until in 1962 he settled in Paris where he had his base for more than 20 years. Kudo’s interest in the ‘natural’ metamorphoses and transformations, of which we are always in the midst, is not only about relations between nature and mankind; it also has a critical, political angle to do with the power and value hierarchies of humanity and culture.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: . Louisiana Museum Archive

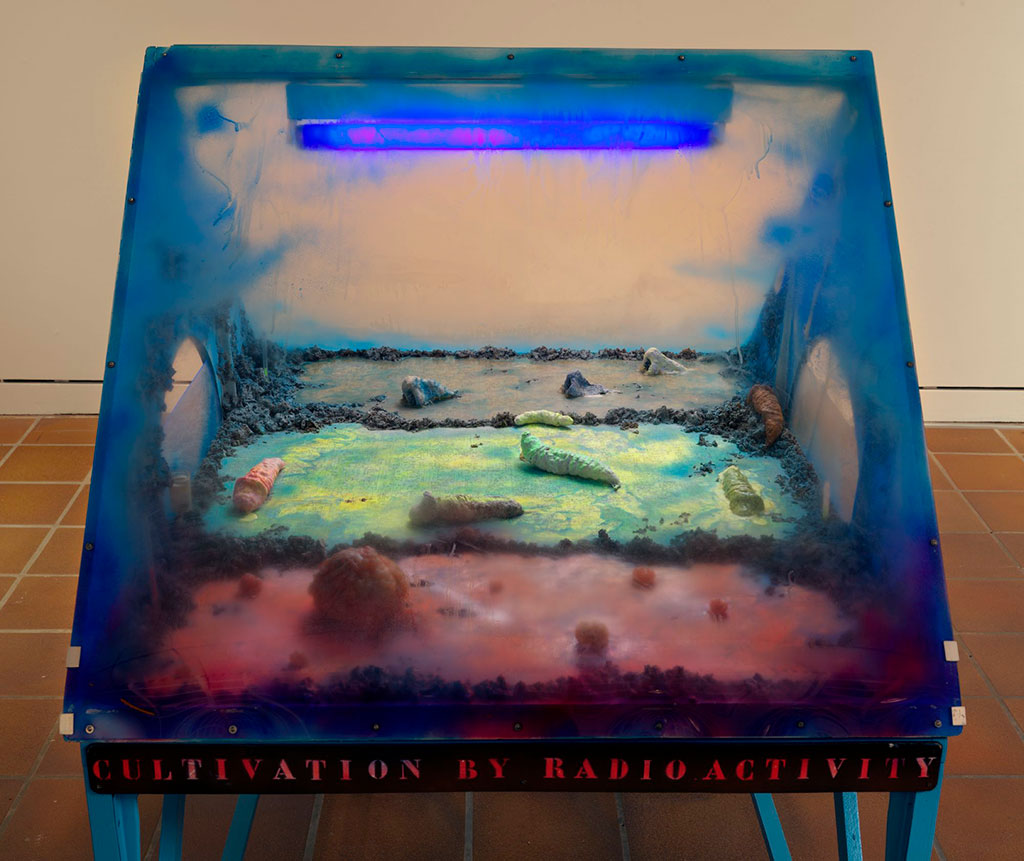

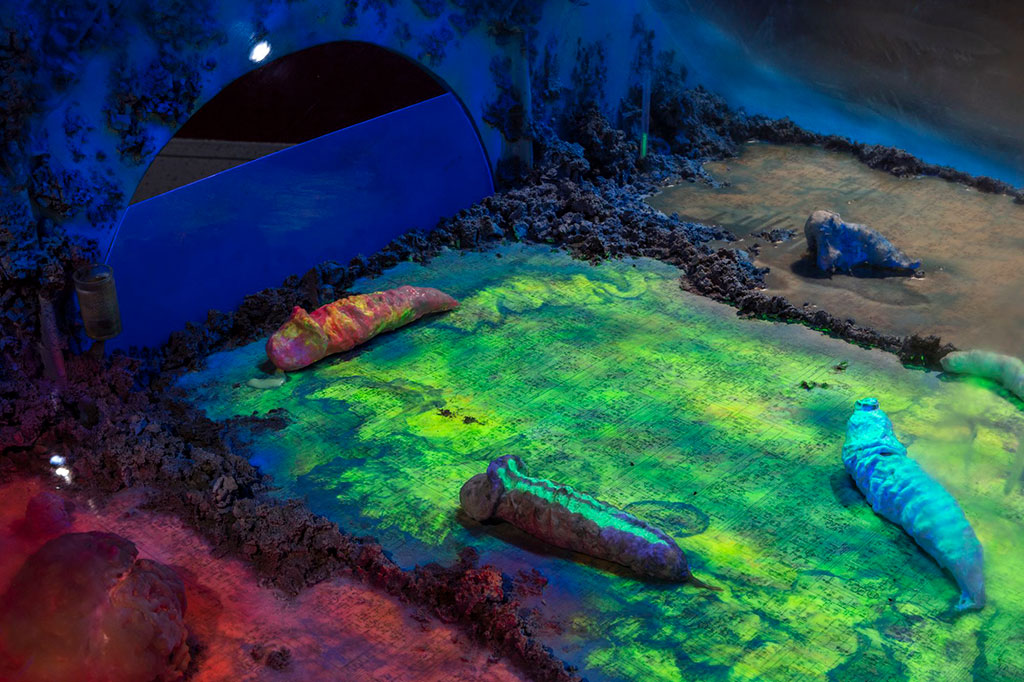

Tetsumi Kudo is currently being rediscovered, yet for many people he will be a new acquaintance. Louisiana’s Museum Collection includes two striking work assemblages by Kudo, and they form the starting point for the exhibition which focuses on the artist’s production in the 1960s-70s and his visualizations of our new ecology – a self-created swamp of polluted nature, technology and decomposed humanity and humanism. The apocalyptic post-war experience of the effects of the atom bomb on humans and the environment is a clear point of departure for Kudo. Without sentimentality, he presents mankind’s technology-fixated self-destruction and environmental decay. But it is not without absurdity and humour that he thematises how new life can develop. “Cultivation” presents approximately 40 works as a concentrated selection of Kudo’s various cultivation environments in which we typically encounter bizarre symbioses of body parts, plants and electronic components. In Kudo’s words, the works are “visual maquettes” or ”models” of our new ecological situation. In buckets, domes and small experimental gardens we see growth environments with plants and isolated limbs; penises, hearts, eyes, flowers, snails and electronic devices germinate and are fused together in small ecosystems. The exhibition also gathers a number of Kudo’s characteristic cages. Here too we find fragments of nature, electronics and human bodies – or sloughed-off, dried-up and abandoned skins of body fragments. The cages are pet cages as we know them from private homes or pet shops. In his small but at the same time large world-pictures Kudo wallows in plastic and synthetic materials and not least visualizes the new ecology by means of non-natural materials and fluorescent colours. In the directly ‘irradiated’ section of the exhibition where the colours glow under ultra-violet light, we find overgrown flowers as well as small, terrarium-like hothouses with carefully conceived, science-fiction-like cultivation experiments with eyes, brains, noses and penises in radioactive environments. Kudo develops a number of major motifs that we find in various constellations in the works in the exhibition. The penis is Kudo’s highly original leitmotif and a multi-faceted symbol – in cocoon-like form a symbol of the transformation potential and the metamorphosis we are constantly undergoing. In other forms, Kudo stages a comical and grotesque deconstruction of phallic dignity and dominance, and in general the penis motif stands as Kudo’s symbol of mankind’s punctured vitality, potency and control in the new environmental processes we might have started, but no longer quite master. Kudo never showed in the US in his lifetime and is little known to the general public. Yet his legacy is huge; his influence can be seen in the work of David Altmejd, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Mike Kelley. “Kudo’s works looked less like sculpture than like movie props from lurid science fiction film” Kelley wrote in 2008. “They did not resemble any other contemporary sculpture I was familiar with, and I admired them greatly.” Paul McCarthy, meanwhile, has been discussing Kudo in lectures since 1968, and talked about him in his book “Low Life Slow Life: Tidebox Tidebook”.

Tetsumi Kudo (23/2/1935-12/11/1990) ,emerged from the radical post-war Tokyo art scene. He was born in Osaka to parents who were painters and teachers. In 1954 he entered the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music and quickly rebelled against the traditional education system, forming collectives and organising events and exhibitions. He stayed in the city after graduation in 1958, flirting with scenes like neo-dada and regularly entering the Yomiuri Independent, an annual salon show that was the biggest contemporary space for emerging art. Alongside abstract paintings incorporating found objects, he created a number of anti-art performances, in one instance creating gesture paintings with his hands and feet using splashed paint on canvases on the floor and walls. By 1960, he was largely working with sculpture and junk materials, making scrubbing brushes that look like sea urchins and cotton gloves shaped like amoebas. In 1961, in protest at the signing of the US/Japan mutual security treaty, Kudo created his breakthrough work, the installation “Philosophy of Impotence”, which took up an entire room at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum as part of the Yomiuri Independent exhibition. He hung the walls and ceiling of the black space with penises sculpted from tape and inlaid with mini-lightbulbs that looked like pre-cum. The approach was different from the work of, say, Yayoi Kusama or Louise Bourgeois. Kudo was not making work about patriarchy or sex; he was looking for something post-sexual, working to “find the ground zero of sex, the ground zero of culture. Also included in the exhibition was a painting Kudo made with black string called “Proliferating Chain Reaction in Limited Pool”. He won a prize for the show, and immediately used the money to go to Paris. Despite not speaking any French, when Kudo arrived in 1962 he managed to hook up with critic Jean-Jacques Lebel, who invited him to enact “happenings”. Allan Kaprow described one of these in his book “Assemblage, Environments and Happenings” (1966): “Kudo as sex priest makes silent sermon with immense papier-mache phallus, then screams in Japanese, caresses public with the phallus, goes into mystic orgasm then collapses”. Kudo wasn’t really the “sex priest” Kaprow thought he was, but given that other performances included giving “products” called “Dry Penis” and “Instant Sperm” to audience members like Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, you can understand the assumption. In Paris, Kudo’s work changed dramatically. He didn’t have a proper studio, so began making smaller objects with kitchen utensils and odd plastic objects. He increasingly referenced nuclear physics with titles like “Proliferous Chain Reaction in X-style Basic Substance”. Boxes became a central motif, resulting in works like 1962’s “Bottled Humanism”, a sculpture of a bloodied plastic foetal thing in a jar labelled “Kudo Co. Ltd”. Kudo later wrote, “We are born from a box (womb), live our lives in a box (apartment), and after death we end up in a box (coffin)”. He developed a very personal visual language, adding moulded body parts to his increasingly grotesque sculptures – eyeballs, melted skin, brains, disembodied hands. Many saw his work as a response to nuclear holocaust and Japanese experience, but Kudo’s emphasis was actually on metamorphosis. “It is not just a question of appearance, since everything is in a state of transformation,” he said. “The body itself is changing”. In the late 60s, he made small terrariums and greenhouses filled with eyeballs, noses, penises and electronic circuitry covered in resin and soil, glowing with fluoro spraypaint. The works were proto post-humanist – a fusion of the organic and inorganic, a utopian vision of post-nuclear ecology he called “cultivation by radioactivity”. In a 1972 solo show at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, Kudo called for a rethink about the relationship between nature, humanity and technology. “Pollution of nature! Decomposition of humanity (humanism)! The end of the world!” he said. “These exclamations are fashionable nowadays but this situation is neither absolutely catastrophic nor fashionable. This is the ineluctable process for reforming ourselves. Behind this situation there is a great possibility of revolution for us personally”. He slowed down in the mid-70s, becoming less confrontational and more introverted, working on a series of birdcage sculptures titled “Portrait of the Artist in Crisis” that saw melting part-figures knitting, praying and playing with string. In 1980 he was hospitalised for alcoholism, and the following year returned to Japan. He split his time between France and Japan for the rest of his life. After being diagnosed with throat cancer in 1987, he began chemo and radiotherapy. During this period he returned to the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music as a teacher. In 1990, at the age of 55, Kudo died of colon cancer.

Info: Curator: Tine Colstrup, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Gl Strandvej 13, Humlebæk, Duration: 5/6/20-10/1/21, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 11:00-23:00, Sun 11:00-18:00, www.louisiana.dk

Right: Tetsumi Kudo, Cultivation by Radioactivity in the Electronic Circuit (detail), 1968, Mixed media, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, © Tetsumi Kudo Adagp, Paris 2020 / VISDA

Right: Tetsumi Kudo, Cultivation by Nature & People Who Are Looking at It, 1970-71, Plastic bucket, plastic, mirrored glass, papier maché, cotton, artificial soil, resin, adhesive, paint, artificial hair, 36 x 23 x 23 cm, Private Collection, © Tetsumi Kudo / Adagp, Paris 2020 / VISDA

Right: Tetsumi Kudo, Souvenir ‘La Mue’, 1967, Mixed Media, 61 x 38 x 24 cm, Private Collection, ©Tetsumi Kudo Adagp, Paris 2020 / VISDA

Right: Tetsumi Kudo, Cultivation by Radioactivity in the Electronic Circuit (Pink Flower), 1968, Plastic, plexiglass, polyester, 65 x 25 x 25 cm, Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, Photo: Jessica Eckert, © Tetsumi Kudo / Adagp, Paris 2020 / VISDA