ART-PRESENTATION:A.R. Penck-How it works

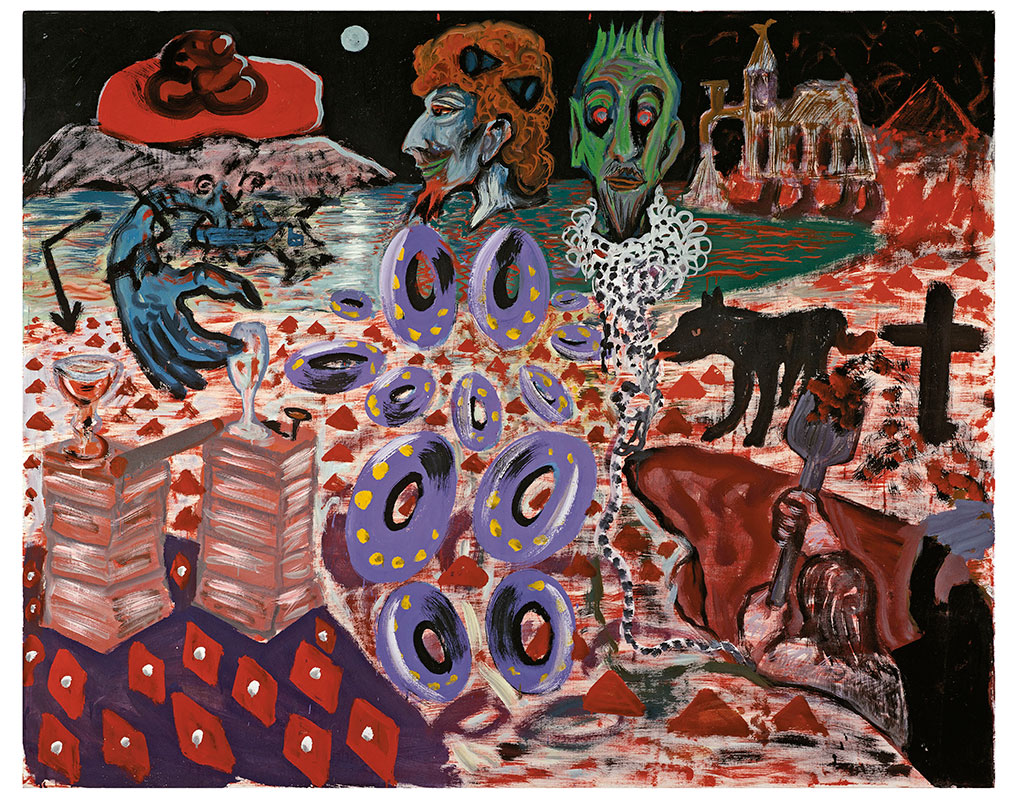

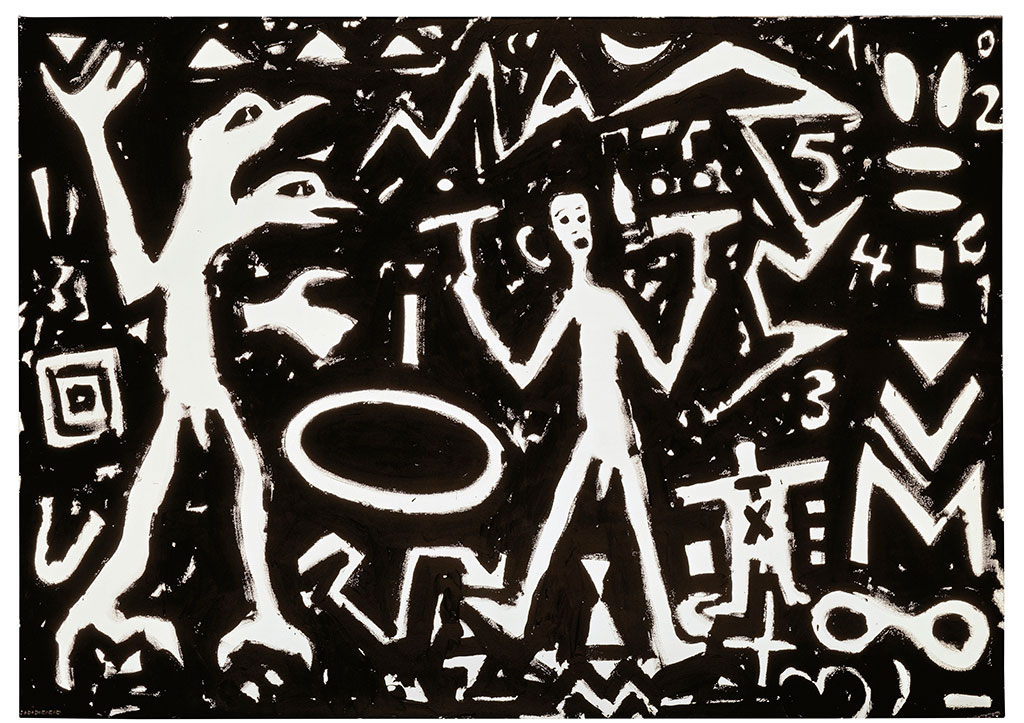

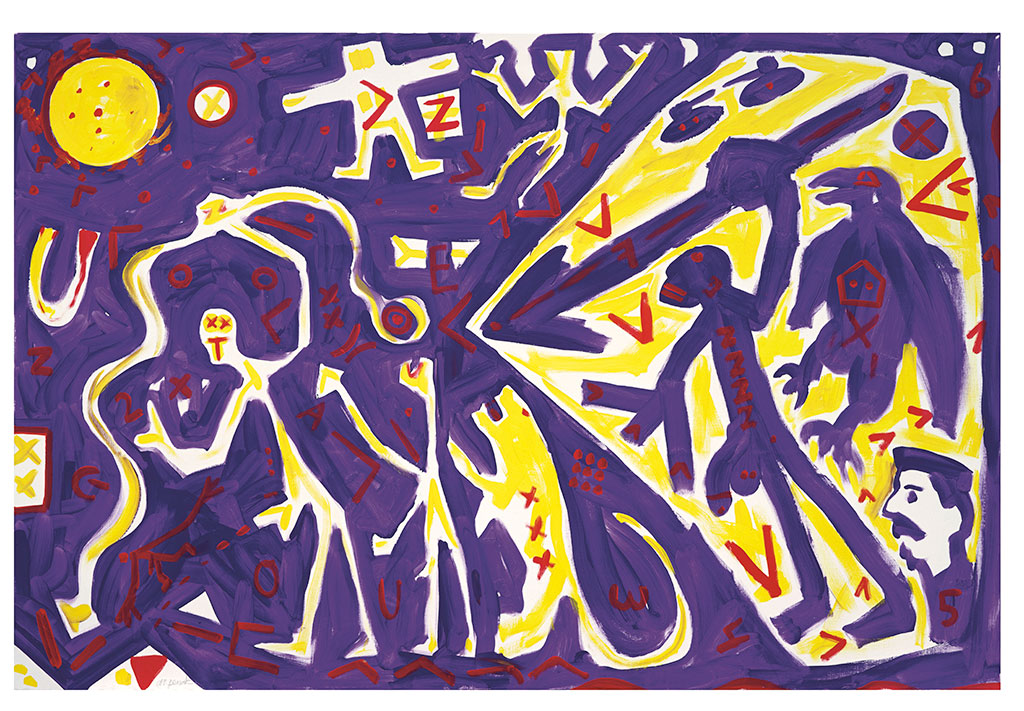

For the past 50 years, A.R. Penck explored how signs, numbers, and symbols could become abstraction. Like his Neo-Expressionist colleagues Penck relied on a style that appeared childlike, even at times resembling cave paintings and outsider art. His paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures attempted to find a universal language, one that could address the trauma, sadness, and loss that followed World War II but that would also affect viewers beyond Germany.

For the past 50 years, A.R. Penck explored how signs, numbers, and symbols could become abstraction. Like his Neo-Expressionist colleagues Penck relied on a style that appeared childlike, even at times resembling cave paintings and outsider art. His paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures attempted to find a universal language, one that could address the trauma, sadness, and loss that followed World War II but that would also affect viewers beyond Germany.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Kunstmuseum Den Haag Archive

The exhibition “A.R. Penck – How it works” brings together over two hundred drawings and paintings plus a number of sculptures. Works both large and small, featuring images that leave an indelible impression and examines how A.R. Penck explored the medium of painting throughout his life. He was driven not by any system or rational narrative, but by apparent chaos and emotion. In every drawing and every painting he set out to create a purely visual space where the imagination could thrive and viewers could lose themselves. Along with Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer and Markus Lüpertz, A.R. Penck (pseudonym of Ralf Winkler) helped paved the way for a new attitude in art after the Second World War. While many young German artists were opting for an abstract idiom, Penck and the others preferred to depict the visible reality of daily life in work that continued a long European figurative tradition. Having attempted unsuccessfully to gain entry into one of several art schools in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germany), Penck resolved to independently pursue art in the mid-1950s. In 1957 he met Georg Baselitz, who became an important friend and influence. During the 1960s Penck developed a figural aesthetic of stick figures and uniform signs and symbols that recall prehistoric drawings. He also sculpted works from cardboard boxes, empty bottles, and other found objects. His aesthetic continued to develop into the early 1970s while he lived in what was then East Berlin. Under an oppressive communist government, Penck and his peers were subjected to secret police (Stasi) surveillance because of the avant-garde nature and political content of their work. Penck used a variety of aliases to sign his work (e.g., Mike Hammer and Mickey Spillane), making it easier to get his paintings out of the GDR. In 1968, after reading the scholarship of geologist Albrecht Penck, who specialized in the Ice Age, the artist settled on the pseudonym A.R. Penck. A year later Penck smuggled his work into Cologne for a solo exhibition at the gallery of Michael Werner, who became a primary supporter of the artist. Although he lived in East Berlin, Penck regularly exhibited his work in West Germany, thanks mostly to Werner’s support. In 1975–76 the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland held a retrospective of Penck’s work. In the late 1970s Penck began working in wood to make totemlike and tribal-art-inspired sculptures. A few years later he started to incorporate bronze and iron into his works, some of which reached monumental scale. Penck was also an accomplished jazz musician and performed regularly. In 1979 he released his first album, “Gostritzer 92”. In 1980 Penck requested permission to leave East Germany and was consequently stripped of his nationality. He settled in Cologne. His move to the West occurred when the Neo-Expressionist movement was gaining momentum, and his “neo-primitivist” style fit in seamlessly with the movement. He forged close friendships with Neo-Expressionist artists Jörg Immendorff and Markus Lüpertz. Penck stayed in the West, exhibiting frequently, but traveled to Israel in the early 1980s and moved around to different cities in Europe, eventually settling in Dublin and Düsseldorf. He was a professor at the Düsseldorf Art Academy for many years, beginning in 1989.

Info: Kunstmuseum Den Haag, Stadhouderslaan 41, The Hague, Duration: 1/6-27/9/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 10:00-17:00, https://www.kunstmuseum.nl/en