TRACES: Teresita Fernández

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Teresita Fernández (12/5/1968- ). Through her practice, she explores perception and the psychology of looking, regularly manipulating light and space to create immersive, intimate, and evocative experiences. Using a range of materials including silk, graphite, onyx, mirrors, glass, and charcoal, her minimalist yet substantive artworks evoke landscapes, the elements, and various natural phenomena, including meteor showers, cloud formations, and the night sky. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Teresita Fernández (12/5/1968- ). Through her practice, she explores perception and the psychology of looking, regularly manipulating light and space to create immersive, intimate, and evocative experiences. Using a range of materials including silk, graphite, onyx, mirrors, glass, and charcoal, her minimalist yet substantive artworks evoke landscapes, the elements, and various natural phenomena, including meteor showers, cloud formations, and the night sky. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

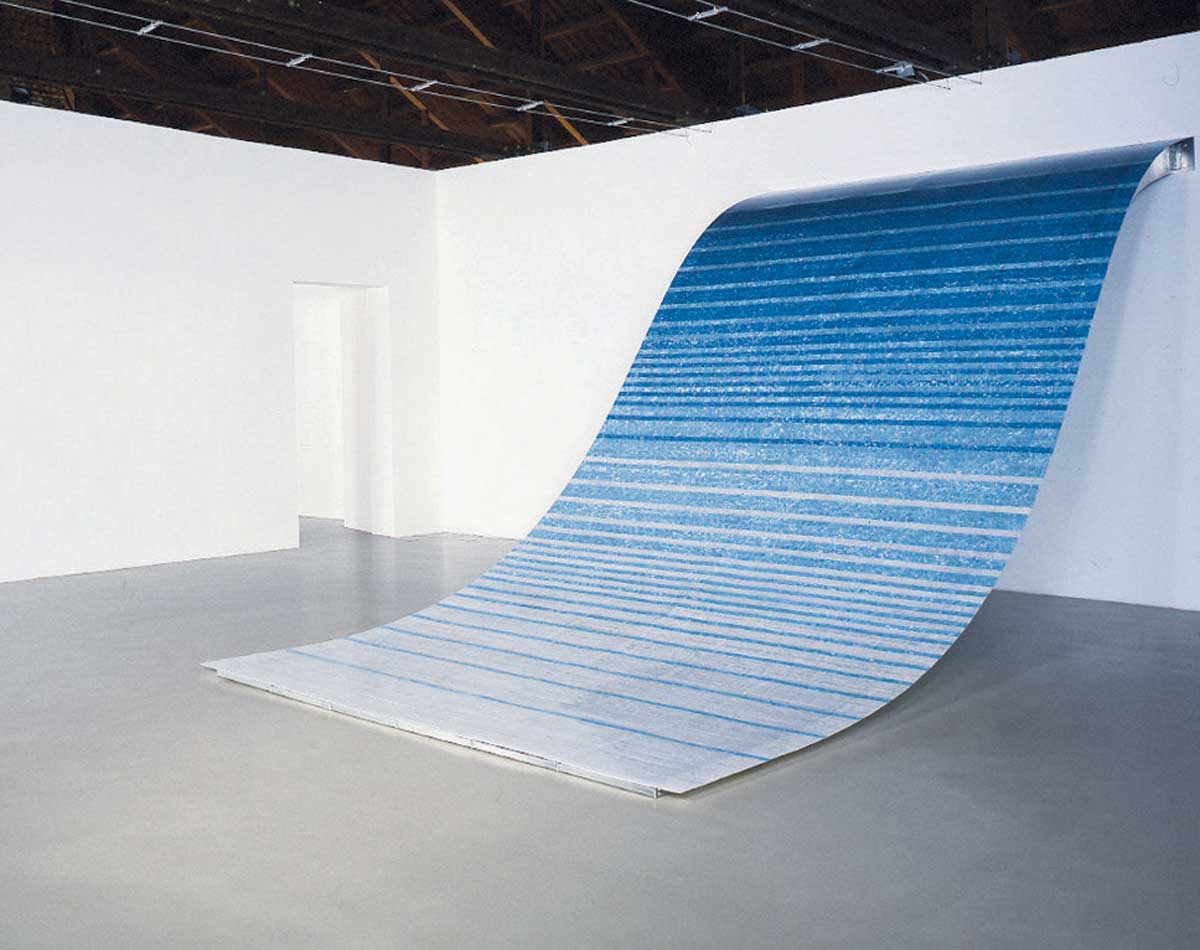

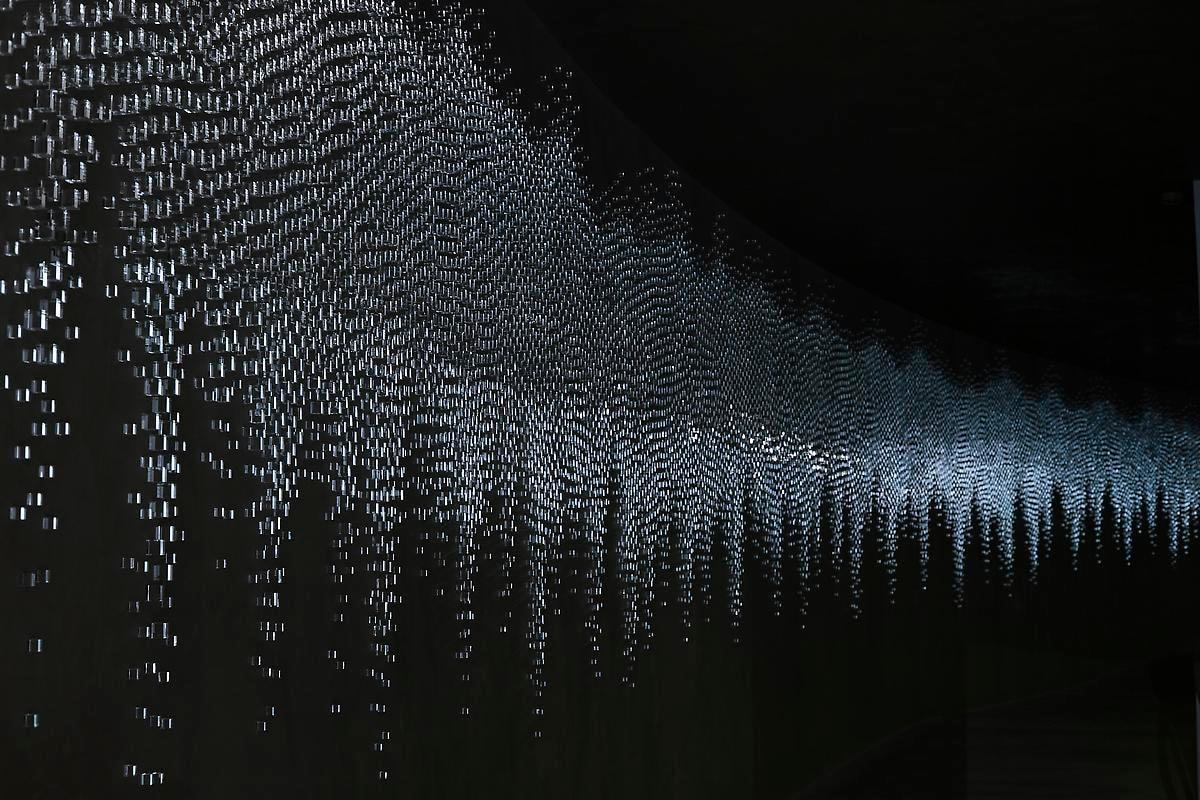

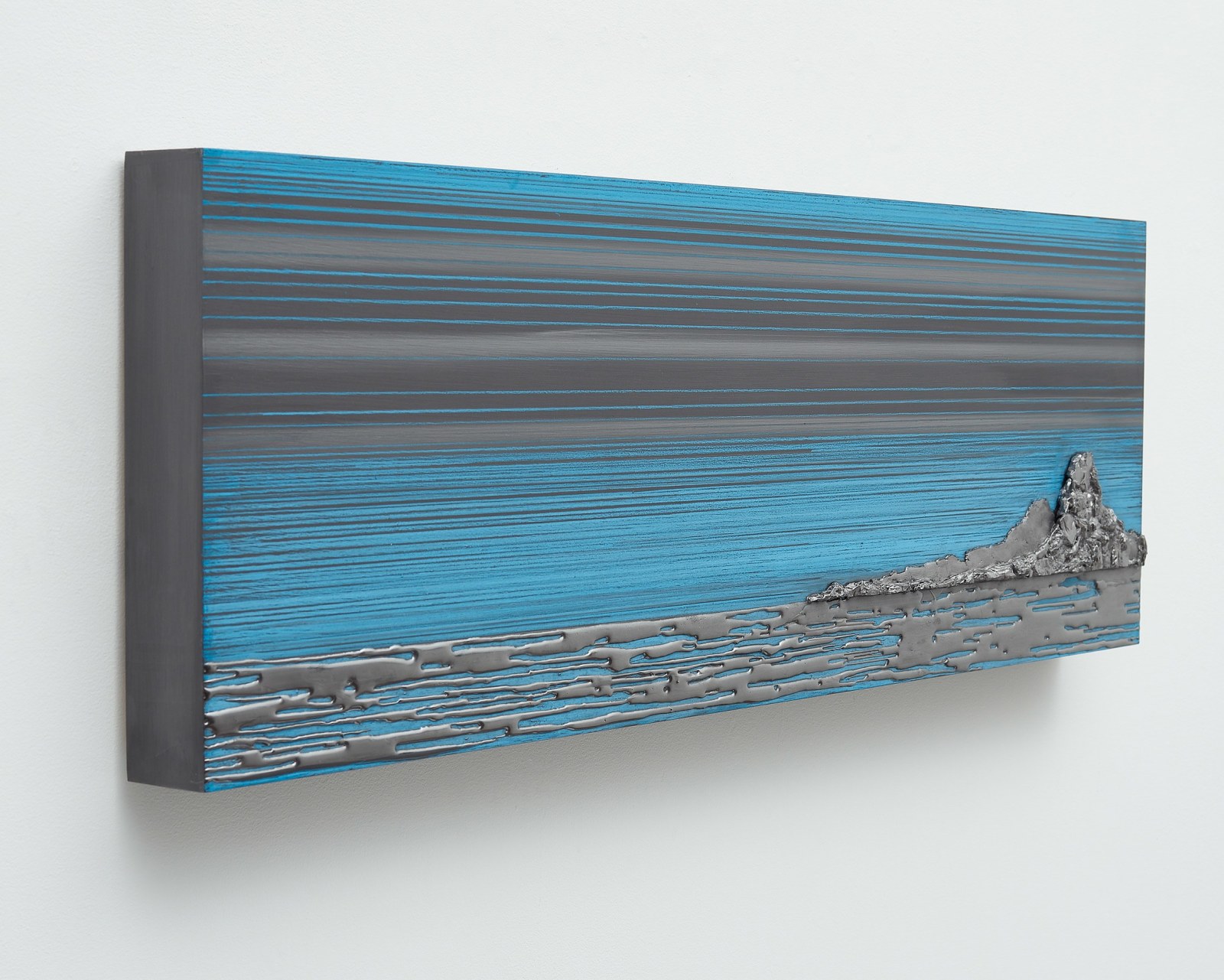

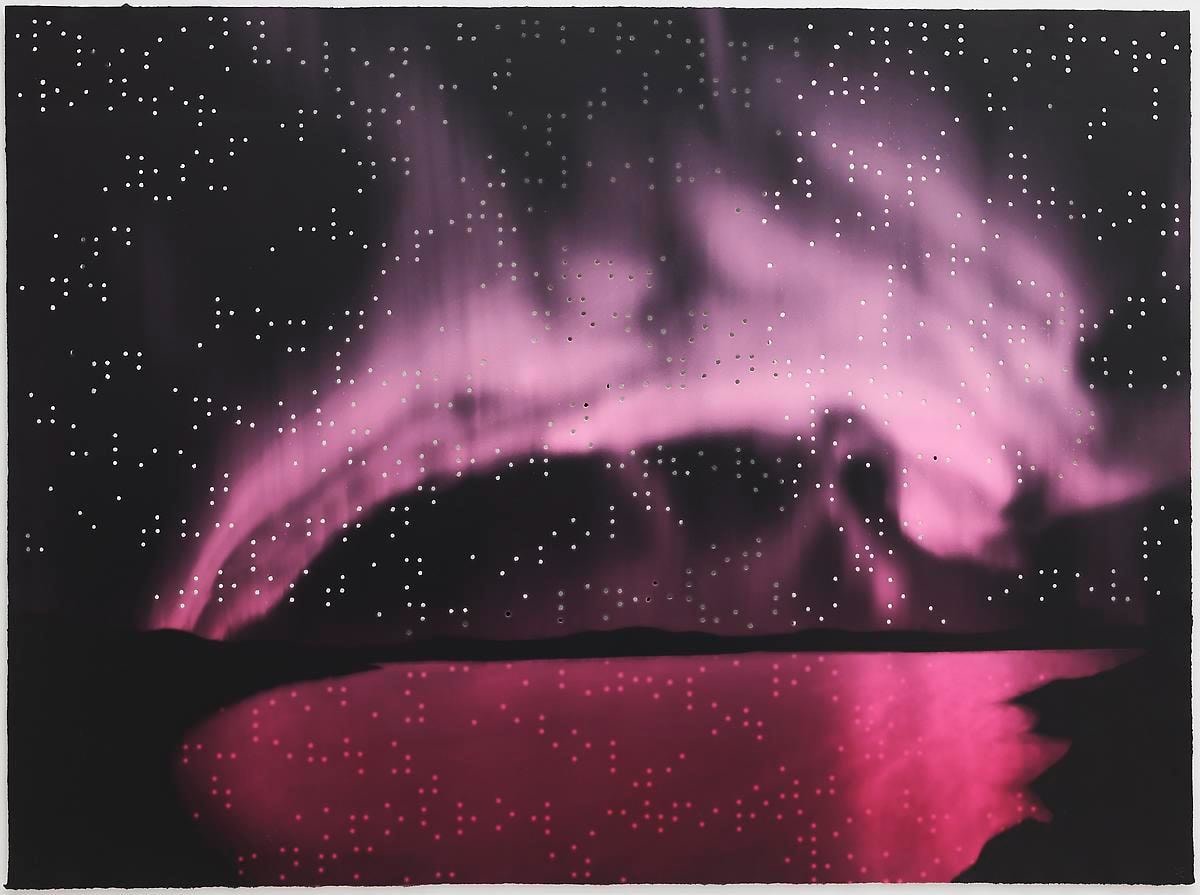

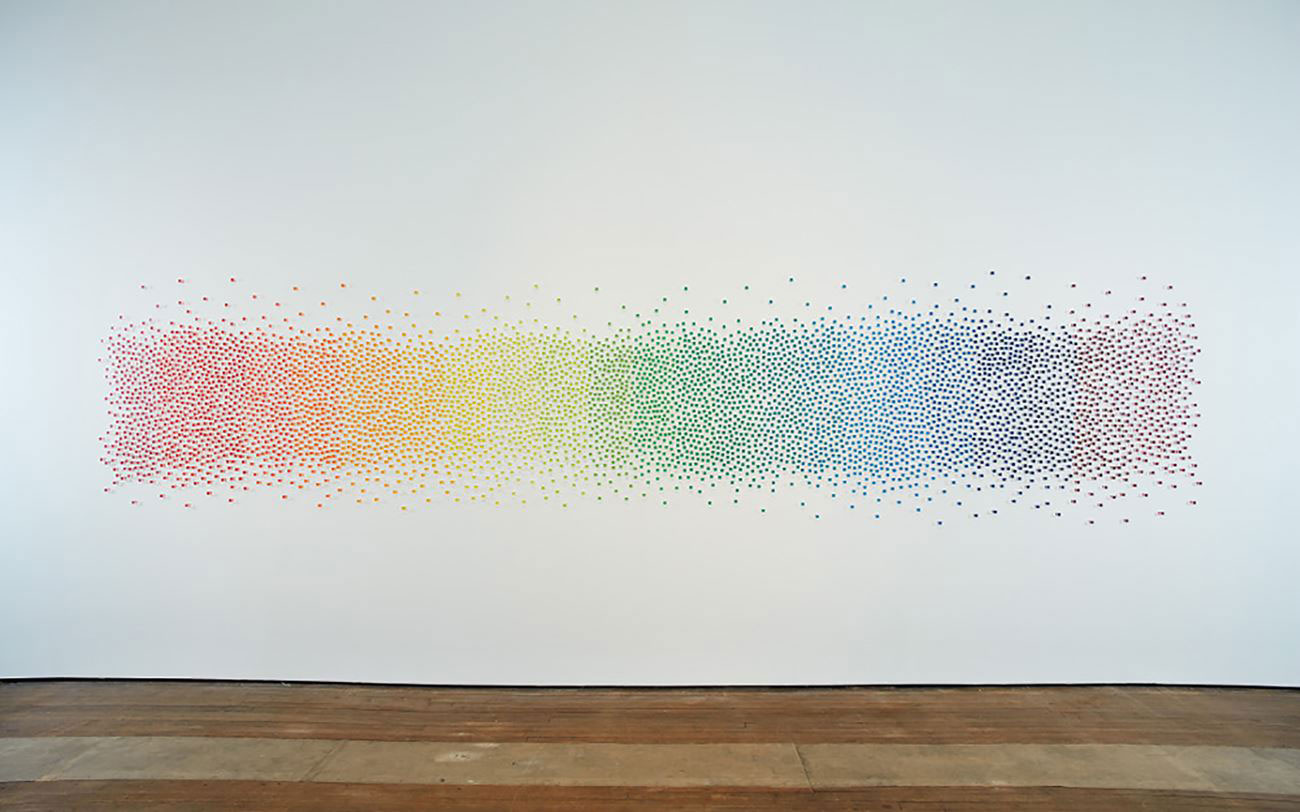

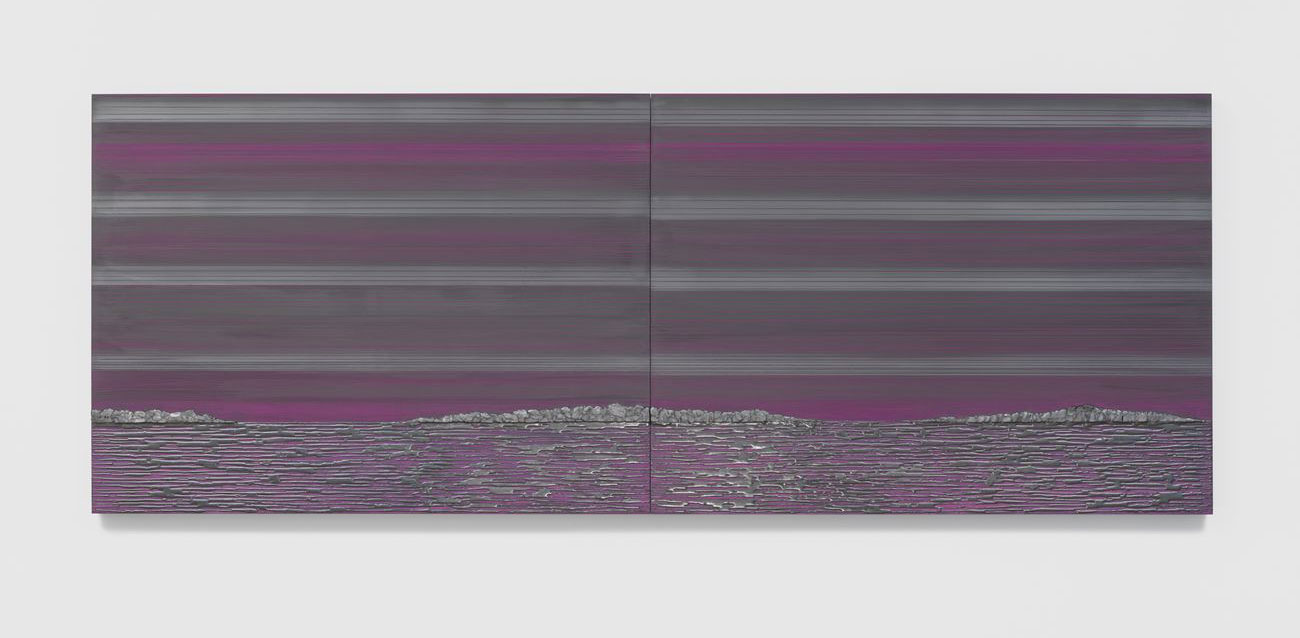

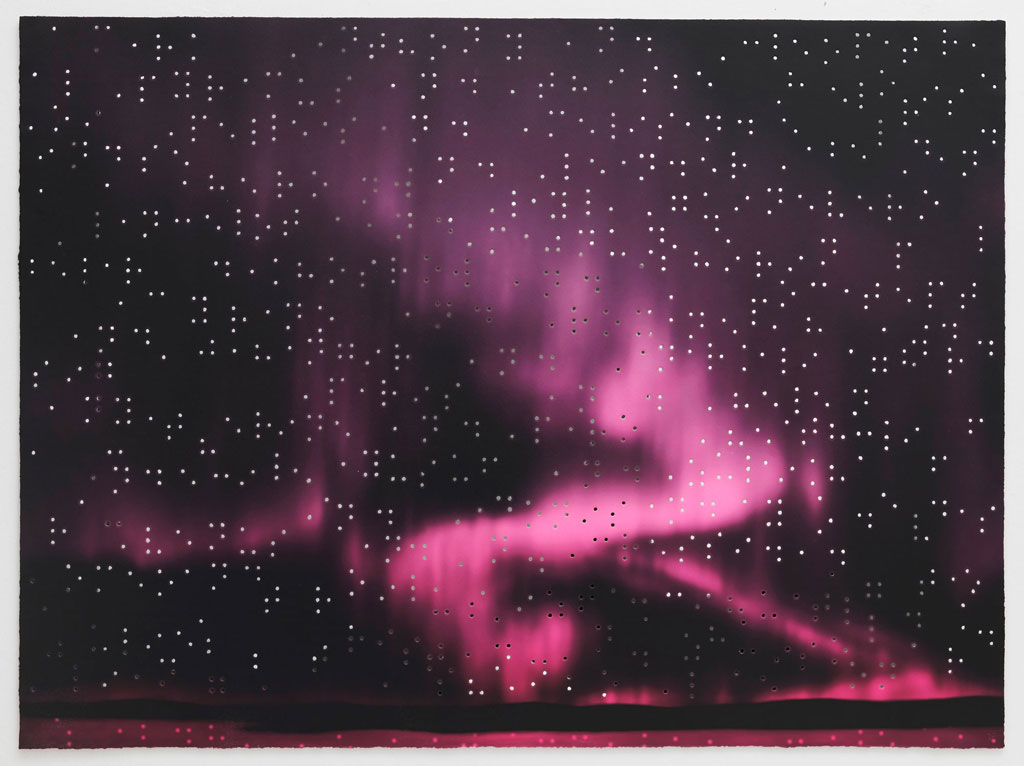

Teresita Fernández was born in 1968 in Miami, her family fled Cuba in July 1959, six months after the Cuban Revolution. As a child, she spent much of her time making things in the atelier of her great aunts and grandmother, all whom had been trained as highly skilled couture seamstresses in Havana, Cuba. Fernández graduated from Southwest Miami High School in 1986. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Florida International University in 1990, and her Masters of Fine Art from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1992. At the core of her work is a paradox: she captures the essence of formless elements such as fire, water, and air using undeniably physical materials. Teresita Fernández is an artist well known for large-scale public sculptures and installations made from such diverse materials as thread, aluminum, acrylic, plastic, and glass beads. Although these are industrial materials, Fernández transforms them into forms and shapes that suggest natural phenomena such as waterfalls or sand dunes. This places her along a lineage of artist who explore the relationship between the power of nature and the development of technology. In her sculptures and drawings, Fernández often leverages non-traditional media to create optical illusions of motion, dissolution, and illumination. Fernández pairing of a conventional subject with an unconventional material reinforces her interest in combining the natural with the industrial or mass-produced. In 1996, Fernández had her first solo exhibition in New York at Deitch Projects, where she transformed the gallery into an empty, indoor swimming pool that was in part inspired by a house designed for Josephine Baker in 1920’s Paris. The following year she was included in an exhibition at New Museum and the group exhibition “The Crystal Stopper” at Lehmann Maupin curated by Carlos Basualdo. In 1997, Fernández lived in Moriya, Ibaraki, during an artist’s residency with Arcus Project. Fernández cites Japanese culture and sensibility as the greatest inspiration to her work as an artist. Fernández continues to visit Japan regularly during the last 18 years and cites her ongoing relationship with Japan as having a significant impact on her and her artwork. Her first solo museum show was at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia in 1999. Soon after that she had solo exhibitions at Site Santa Fe, Castello di Rivoli, and The Centro de Arte Contemporaneo, in Málaga, Spain. Fernández’s site-specific project titled “Hothouse” was installed at The Museum of Modern Art. The work was commission as part of Open Ends, the third and final cycle of MoMA2000. The installation, a sprawling vine-like pattern (white on the front and green on the back), meandered across the glass looking out to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The Public Art Fund commissioned Fernández’s “Bamboo Cinema” (2001) in New York’s Madison Square Park. The sculpture, a maze-like form made of concentric circles that functioned like an early cinematic device, was made of translucent elements that optically shifted the surroundings like an animated filmstrip. The vertical elements of the sculpture were made of extruded polycarbonate tubes of different diameters that had a green-hued stripe pattern embedded into them. The transparent tubes allowed different degrees of visibility from every angle. As in the earliest examples of cinematic devices, the vertical lines acted as a continuous shutter, constantly interrupting any movement so that it appeared to flicker. At age thirty-five, she became the youngest artist commissioned by the Seattle Art Museum for the museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park. Her permanently installed work, “Seattle Cloud Cover” (2006), allows visitors to walk under a block-long covered skyway while viewing the city’s skyline appearing through tiny holes in color-saturated glass. In 2005, she created “Fire” during her residency at The Fabric Workshop and Museum that was constructed using thousands of silk threads. The dyed silk threads were held taut between two rings and suspended from the ceiling, creating a unique optical illusion of transparency and dense color that appeared to vibrate when experienced by the moving viewer. In 2009, The Blanton Museum of Art, commissioned the large permanent work titled “Stacked Waters” that occupies the museum’s Rapoport Atrium. Stacked Waters consists of 3,100 square feet of custom-cast acrylic that covers the walls in a striped pattern. The work’s title alludes to artist Donald Judd’s “stack” sculptures (series of identical boxes installed vertically along wall surfaces) as well as to his sculptural explorations of box interiors. Fernández noticed how The Blanton’s atrium functions like a box, and given its architectural nods to the arches of Roman baths and cisterns, she sought to fill its spatial volume with an illusion of water. In 2011, President Obama appointed Fernández to the serve on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, a federal panel that advises the President, Congress, and governmental agencies on national matters of design and aesthetics. She is the first Latina to serve on the Commission, and the second person of Latino heritage to serve on the CFA in its over 100-year history. Forty years before her appointment, the last Cuban Ambassador to the United States Nicolas Arroyo sat on the panel from 1971 to 1976.

Teresita Fernández was born in 1968 in Miami, her family fled Cuba in July 1959, six months after the Cuban Revolution. As a child, she spent much of her time making things in the atelier of her great aunts and grandmother, all whom had been trained as highly skilled couture seamstresses in Havana, Cuba. Fernández graduated from Southwest Miami High School in 1986. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Florida International University in 1990, and her Masters of Fine Art from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1992. At the core of her work is a paradox: she captures the essence of formless elements such as fire, water, and air using undeniably physical materials. Teresita Fernández is an artist well known for large-scale public sculptures and installations made from such diverse materials as thread, aluminum, acrylic, plastic, and glass beads. Although these are industrial materials, Fernández transforms them into forms and shapes that suggest natural phenomena such as waterfalls or sand dunes. This places her along a lineage of artist who explore the relationship between the power of nature and the development of technology. In her sculptures and drawings, Fernández often leverages non-traditional media to create optical illusions of motion, dissolution, and illumination. Fernández pairing of a conventional subject with an unconventional material reinforces her interest in combining the natural with the industrial or mass-produced. In 1996, Fernández had her first solo exhibition in New York at Deitch Projects, where she transformed the gallery into an empty, indoor swimming pool that was in part inspired by a house designed for Josephine Baker in 1920’s Paris. The following year she was included in an exhibition at New Museum and the group exhibition “The Crystal Stopper” at Lehmann Maupin curated by Carlos Basualdo. In 1997, Fernández lived in Moriya, Ibaraki, during an artist’s residency with Arcus Project. Fernández cites Japanese culture and sensibility as the greatest inspiration to her work as an artist. Fernández continues to visit Japan regularly during the last 18 years and cites her ongoing relationship with Japan as having a significant impact on her and her artwork. Her first solo museum show was at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia in 1999. Soon after that she had solo exhibitions at Site Santa Fe, Castello di Rivoli, and The Centro de Arte Contemporaneo, in Málaga, Spain. Fernández’s site-specific project titled “Hothouse” was installed at The Museum of Modern Art. The work was commission as part of Open Ends, the third and final cycle of MoMA2000. The installation, a sprawling vine-like pattern (white on the front and green on the back), meandered across the glass looking out to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The Public Art Fund commissioned Fernández’s “Bamboo Cinema” (2001) in New York’s Madison Square Park. The sculpture, a maze-like form made of concentric circles that functioned like an early cinematic device, was made of translucent elements that optically shifted the surroundings like an animated filmstrip. The vertical elements of the sculpture were made of extruded polycarbonate tubes of different diameters that had a green-hued stripe pattern embedded into them. The transparent tubes allowed different degrees of visibility from every angle. As in the earliest examples of cinematic devices, the vertical lines acted as a continuous shutter, constantly interrupting any movement so that it appeared to flicker. At age thirty-five, she became the youngest artist commissioned by the Seattle Art Museum for the museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park. Her permanently installed work, “Seattle Cloud Cover” (2006), allows visitors to walk under a block-long covered skyway while viewing the city’s skyline appearing through tiny holes in color-saturated glass. In 2005, she created “Fire” during her residency at The Fabric Workshop and Museum that was constructed using thousands of silk threads. The dyed silk threads were held taut between two rings and suspended from the ceiling, creating a unique optical illusion of transparency and dense color that appeared to vibrate when experienced by the moving viewer. In 2009, The Blanton Museum of Art, commissioned the large permanent work titled “Stacked Waters” that occupies the museum’s Rapoport Atrium. Stacked Waters consists of 3,100 square feet of custom-cast acrylic that covers the walls in a striped pattern. The work’s title alludes to artist Donald Judd’s “stack” sculptures (series of identical boxes installed vertically along wall surfaces) as well as to his sculptural explorations of box interiors. Fernández noticed how The Blanton’s atrium functions like a box, and given its architectural nods to the arches of Roman baths and cisterns, she sought to fill its spatial volume with an illusion of water. In 2011, President Obama appointed Fernández to the serve on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, a federal panel that advises the President, Congress, and governmental agencies on national matters of design and aesthetics. She is the first Latina to serve on the Commission, and the second person of Latino heritage to serve on the CFA in its over 100-year history. Forty years before her appointment, the last Cuban Ambassador to the United States Nicolas Arroyo sat on the panel from 1971 to 1976.