TRACES: James Turell

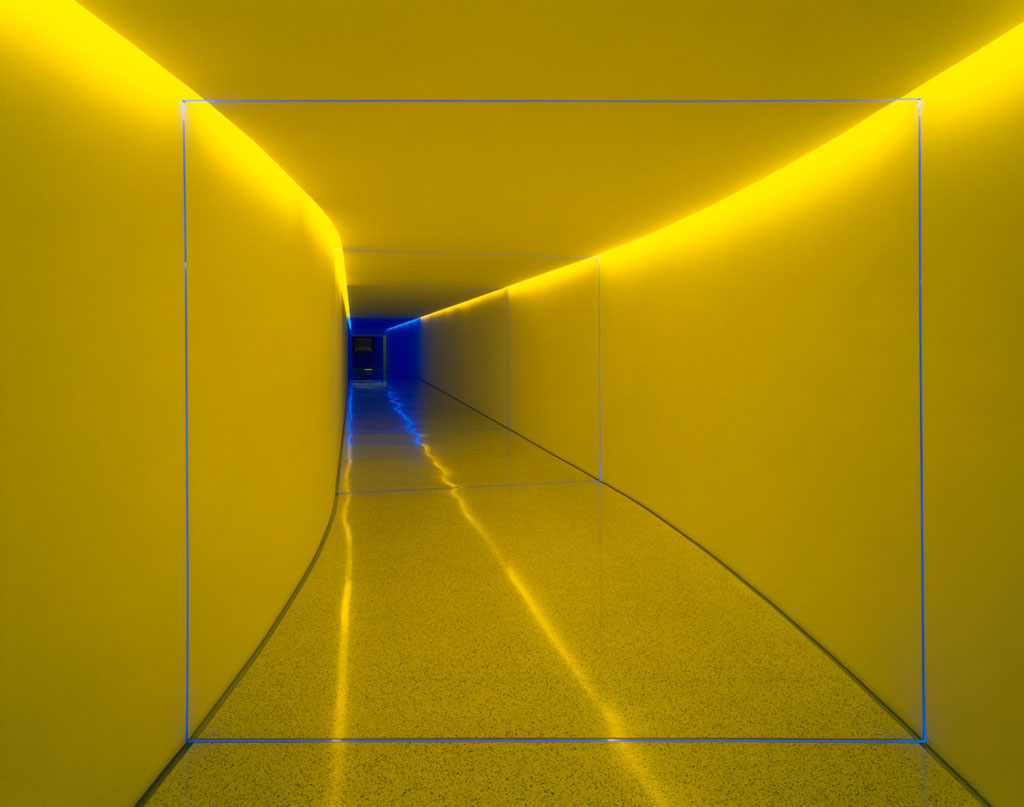

Today is the occasion to bear in mind , James Turrell (6/5/1943- ). Informed by his training in perceptual psychology and a childhood fascination with light, Turrell began experimenting with light as a medium in southern California in the mid-1960’s. Turrell, an avid pilot who has logged over 12.000 hours flying, considers the sky as his studio, material and canvas. His work lies at the intersection of two ideas: that art can be made with non-traditional materials, and that an artwork might be an idea or an experience, as opposed to a thing. Turrell transforms light into art by manipulating the viewer’s experience of it, testing the limits of these two ideas, both of which are fundamental to Conceptual art.

Today is the occasion to bear in mind , James Turrell (6/5/1943- ). Informed by his training in perceptual psychology and a childhood fascination with light, Turrell began experimenting with light as a medium in southern California in the mid-1960’s. Turrell, an avid pilot who has logged over 12.000 hours flying, considers the sky as his studio, material and canvas. His work lies at the intersection of two ideas: that art can be made with non-traditional materials, and that an artwork might be an idea or an experience, as opposed to a thing. Turrell transforms light into art by manipulating the viewer’s experience of it, testing the limits of these two ideas, both of which are fundamental to Conceptual art.

By Dimitris Lempesis

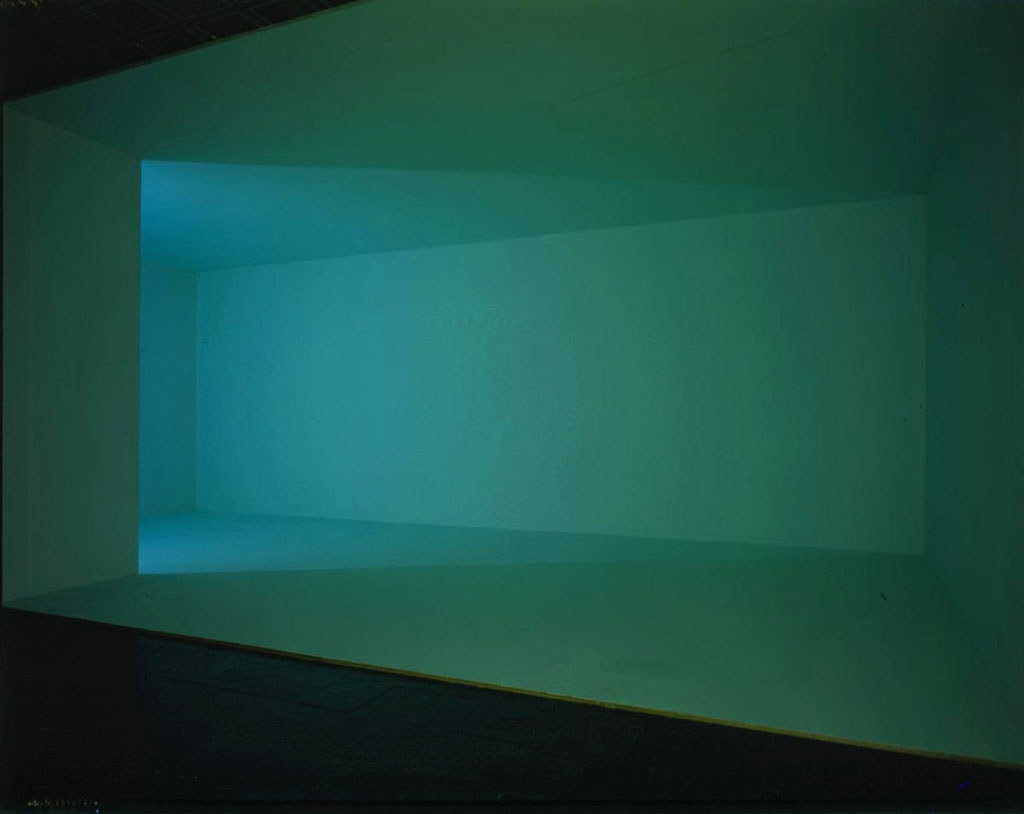

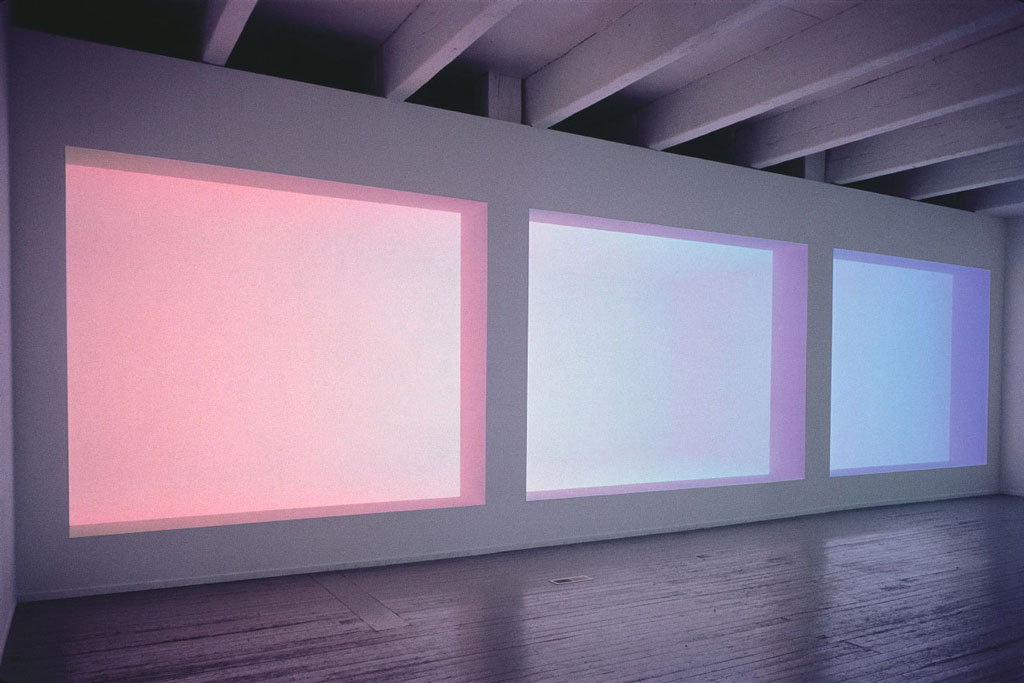

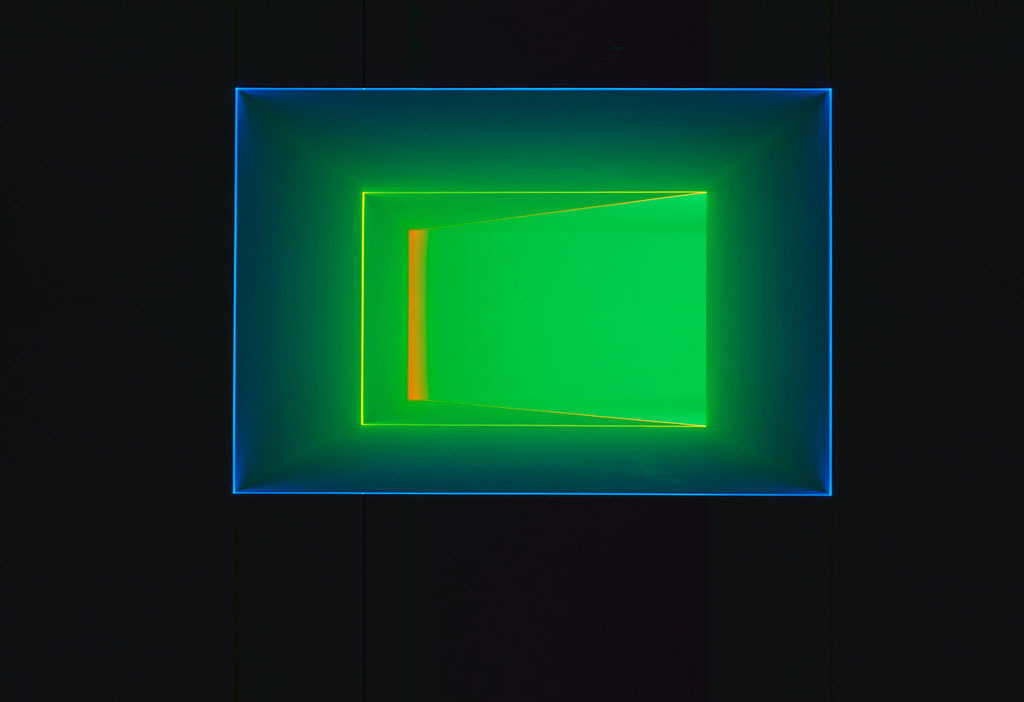

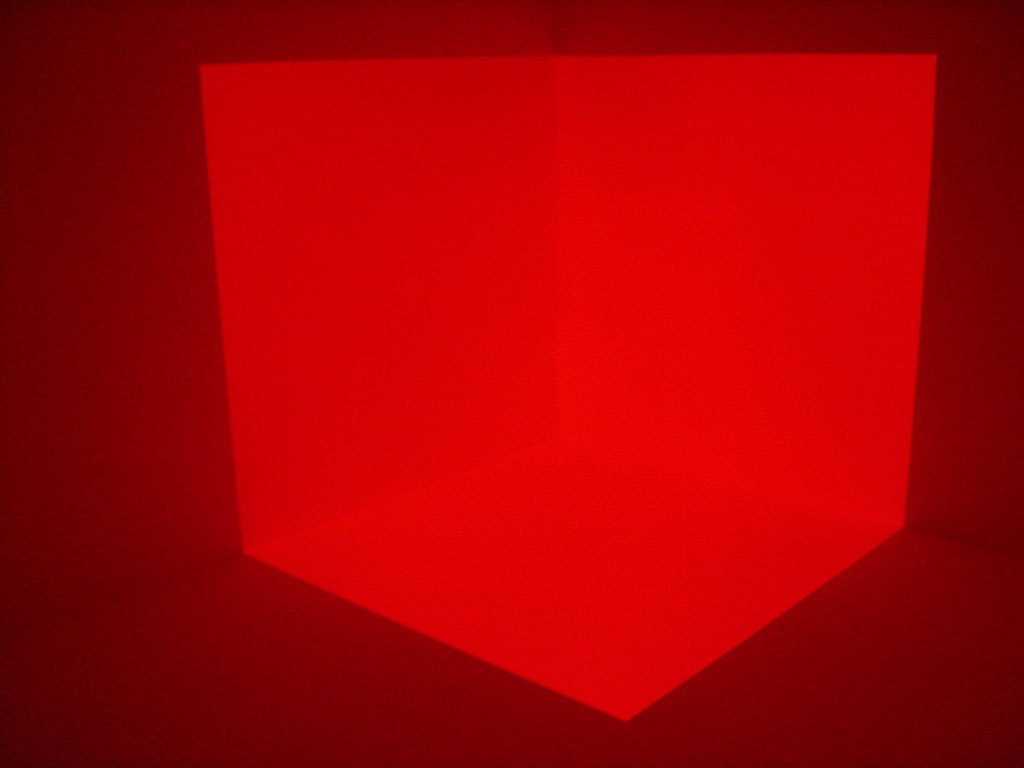

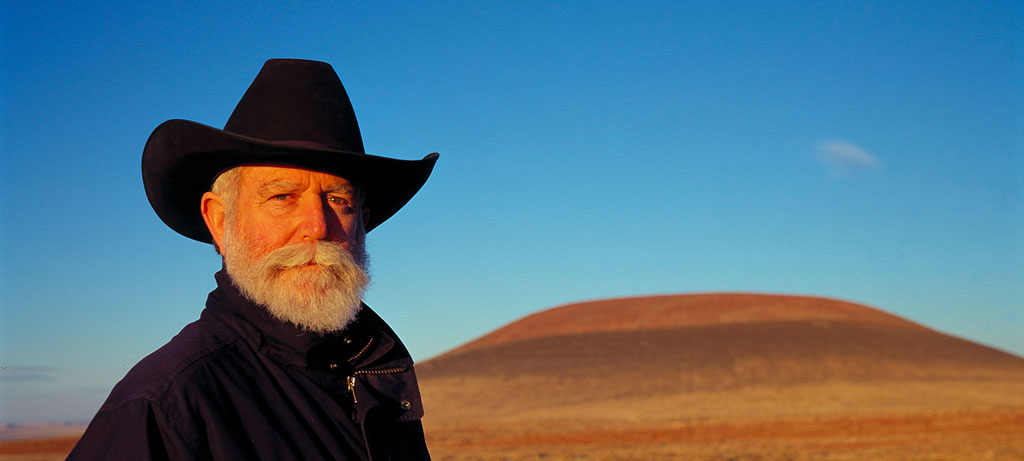

James Turrell was born into a Quaker family in Los Angeles in 1943. He tells a story of sitting in the Quaker meeting house with his grandmother when he was five or six years old. When everyone closed their eyes at the beginning of the meeting, he asked his grandmother what they were supposed to be doing. She told him: “Just wait, we’re going inside to greet the light.'” Arguably this episode greatly influenced his early fascination with light. Turrell got his pilot’s license at 16 years old, following in the footsteps of his late father, who had been an aeronautical engineer. Because of his Quaker background, he was sent for alternative service to Laos during the Vietnam war. He flew U2 planes (ultra-high altitude aircraft developed by the U.S. Air Force for reconnaissance). Flying these secret missions over Tibet and the Himalayas exposed him to changes in vision at high altitude. This attuned him to extraordinary meteorological phenomena. According to Turrell, his career as an artist began with a visual misperception. As a psychology major at Pomona College in 1965, he enjoyed art history, and especially the works of art by Mark Rothko he saw during his art history lectures. He was later disappointed on a trip to New York when he saw his first canvas by Rothko, which lacked the glow it appeared to have when shown via slide projector. The fact that a projected image of a Rothko might possess a glow that exceeded the original was Turrell’s initial impetus for becoming a light-based artist. Turrell went on to pursue studio art at the University of California, Irvine, and upon graduating in 1966, he rented a large space in the abandoned Santa Monica Hotel that would serve as his studio for the next eight years. In it he conducted laboratory-like explorations using the architecture, exterior light, and projectors to mold light as if it were a material substance that could be shaped. Some of his first light-based works were “Projection Pieces”, so-called because the projector beams created the hologram of a geometric shape, further adapted through structural cuts in the building itself. In this way, the changing light of the outside environment – be it a gradual turn to dusk or passing headlights – also impacted the viewer’s perception. In 1967, the Pasadena Art Museum held Turrell’s first solo exhibition, displaying some of these “Projection Pieces”. This exhibition established his reputation. Turrell was part of a generation accustomed to enormous advancements in technology and the excitement of the space race. In 1968 and 1969, he, along with artist Robert Irwin, worked on the Art and Technology program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with Ed Wortz, a scientist at a Southern California aerospace firm. Turrell was considered a member of the Light and Space Movement, a Southern California art movement of the last 60s and 70s. Although this group was only loosely affiliated in terms of the art being produced, Turrell maintained friendships with his artist peers such as Irwin, bonding over an interest in light and technology that was largely unexplored among East Coast artists at the time. Turrell received an MFA from the Claremont Graduate School in Claremont, California in 1973. The massive and ambitious “Roden Crater Project” has been Turrell’s main work since 1977, when, with the help of the DIA foundation, he purchased the site of an extinct volcano in northwestern Arizona near Flagstaff. For years he had searched for a large site that was isolated from the lights of civilization and raised above the surrounding land. Always an avid aviator and independent spirit, he flew six days a week for seven months between the Western foothills of the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Coast, sleeping under the wing of his plane. Finally, he found Roden Crater. He wanted to create a site where the visitor could experience “celestial vaulting” which Roden Crater, at 1.659 meters above sea level and with a natural concave bowl, was well suited for. This phenomena, in which space seems to curve at the edges of your perception, was something Turrell had experienced while flying close to ground. Roden Crater is also a perfect site because nearby Flagstaff was one of the first places in the United States to create light pollution laws, enabling the visitor an undisturbed view of the heavens. In 1984, at age 41, Turrell was the first artist to become a MacArthur Fellow, the so-called “genius” award. He spent the award on the Roden Crater project, bought surrounding land and started a cattle ranch to fund the Crater project. His career has been further supported by the sale of drawings and plans of the crater site and by his light installations, giving him a reputation as a sculptor of light. In addition to “Projection Pieces”, “Shallow Space Constructions” and “Wedgeworks” were pioneered in the Mendota rooms and honed later in different installations in museums and galleries. From 1976 to today, Turrell has used Space Division Constructions to create the illusion of a seemingly infinite room through an aperture. Also since 1976, the artist has created “Ganzfelds” in order to create an experience of light that gets rid of all depth for the viewer so that they are engulfed in light. “Perceptual Cells”, a series begun in 1989, are enclosed chambers designed for an individual in which the intense experience of light is only partially physical – the rest of the light effect is created in the stimulated brain. These light installations have been exhibited successfully internationally, but bringing the cosmos closer through Roden Crater remains his obsession, To this day, Turrell remains an avid aviator and a cattle rancher as well as an artist. The Roden Crater, though unfinished, has already been transformed over the past 30 years into a celestial observatory that intertwines art, architecture, and astronomy. When completed, the project will contain 21 viewing spaces and six tunnels. While this project is not yet open to the public, several smaller projects of independent architectural spaces (Skyspaces) emulate chambers in the Roden Crater. Over 100 Skyspaces can be viewed in museums and countries across the world.

James Turrell was born into a Quaker family in Los Angeles in 1943. He tells a story of sitting in the Quaker meeting house with his grandmother when he was five or six years old. When everyone closed their eyes at the beginning of the meeting, he asked his grandmother what they were supposed to be doing. She told him: “Just wait, we’re going inside to greet the light.'” Arguably this episode greatly influenced his early fascination with light. Turrell got his pilot’s license at 16 years old, following in the footsteps of his late father, who had been an aeronautical engineer. Because of his Quaker background, he was sent for alternative service to Laos during the Vietnam war. He flew U2 planes (ultra-high altitude aircraft developed by the U.S. Air Force for reconnaissance). Flying these secret missions over Tibet and the Himalayas exposed him to changes in vision at high altitude. This attuned him to extraordinary meteorological phenomena. According to Turrell, his career as an artist began with a visual misperception. As a psychology major at Pomona College in 1965, he enjoyed art history, and especially the works of art by Mark Rothko he saw during his art history lectures. He was later disappointed on a trip to New York when he saw his first canvas by Rothko, which lacked the glow it appeared to have when shown via slide projector. The fact that a projected image of a Rothko might possess a glow that exceeded the original was Turrell’s initial impetus for becoming a light-based artist. Turrell went on to pursue studio art at the University of California, Irvine, and upon graduating in 1966, he rented a large space in the abandoned Santa Monica Hotel that would serve as his studio for the next eight years. In it he conducted laboratory-like explorations using the architecture, exterior light, and projectors to mold light as if it were a material substance that could be shaped. Some of his first light-based works were “Projection Pieces”, so-called because the projector beams created the hologram of a geometric shape, further adapted through structural cuts in the building itself. In this way, the changing light of the outside environment – be it a gradual turn to dusk or passing headlights – also impacted the viewer’s perception. In 1967, the Pasadena Art Museum held Turrell’s first solo exhibition, displaying some of these “Projection Pieces”. This exhibition established his reputation. Turrell was part of a generation accustomed to enormous advancements in technology and the excitement of the space race. In 1968 and 1969, he, along with artist Robert Irwin, worked on the Art and Technology program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with Ed Wortz, a scientist at a Southern California aerospace firm. Turrell was considered a member of the Light and Space Movement, a Southern California art movement of the last 60s and 70s. Although this group was only loosely affiliated in terms of the art being produced, Turrell maintained friendships with his artist peers such as Irwin, bonding over an interest in light and technology that was largely unexplored among East Coast artists at the time. Turrell received an MFA from the Claremont Graduate School in Claremont, California in 1973. The massive and ambitious “Roden Crater Project” has been Turrell’s main work since 1977, when, with the help of the DIA foundation, he purchased the site of an extinct volcano in northwestern Arizona near Flagstaff. For years he had searched for a large site that was isolated from the lights of civilization and raised above the surrounding land. Always an avid aviator and independent spirit, he flew six days a week for seven months between the Western foothills of the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Coast, sleeping under the wing of his plane. Finally, he found Roden Crater. He wanted to create a site where the visitor could experience “celestial vaulting” which Roden Crater, at 1.659 meters above sea level and with a natural concave bowl, was well suited for. This phenomena, in which space seems to curve at the edges of your perception, was something Turrell had experienced while flying close to ground. Roden Crater is also a perfect site because nearby Flagstaff was one of the first places in the United States to create light pollution laws, enabling the visitor an undisturbed view of the heavens. In 1984, at age 41, Turrell was the first artist to become a MacArthur Fellow, the so-called “genius” award. He spent the award on the Roden Crater project, bought surrounding land and started a cattle ranch to fund the Crater project. His career has been further supported by the sale of drawings and plans of the crater site and by his light installations, giving him a reputation as a sculptor of light. In addition to “Projection Pieces”, “Shallow Space Constructions” and “Wedgeworks” were pioneered in the Mendota rooms and honed later in different installations in museums and galleries. From 1976 to today, Turrell has used Space Division Constructions to create the illusion of a seemingly infinite room through an aperture. Also since 1976, the artist has created “Ganzfelds” in order to create an experience of light that gets rid of all depth for the viewer so that they are engulfed in light. “Perceptual Cells”, a series begun in 1989, are enclosed chambers designed for an individual in which the intense experience of light is only partially physical – the rest of the light effect is created in the stimulated brain. These light installations have been exhibited successfully internationally, but bringing the cosmos closer through Roden Crater remains his obsession, To this day, Turrell remains an avid aviator and a cattle rancher as well as an artist. The Roden Crater, though unfinished, has already been transformed over the past 30 years into a celestial observatory that intertwines art, architecture, and astronomy. When completed, the project will contain 21 viewing spaces and six tunnels. While this project is not yet open to the public, several smaller projects of independent architectural spaces (Skyspaces) emulate chambers in the Roden Crater. Over 100 Skyspaces can be viewed in museums and countries across the world.