TRACES: William Kentridge

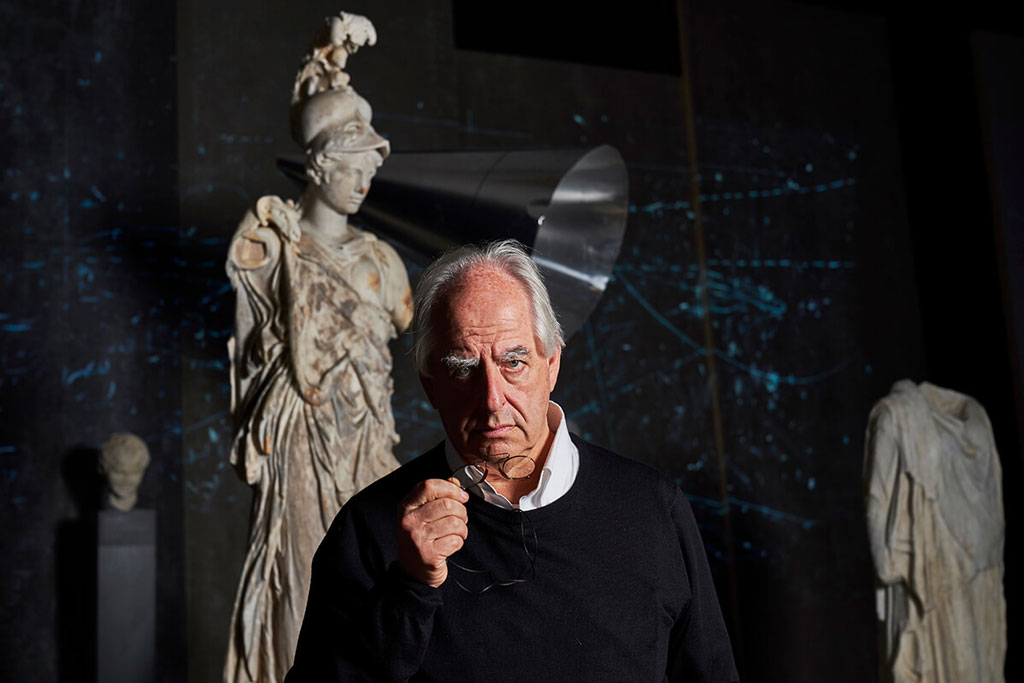

Today is the occasion to bear in mind William Kentridge (28/4/1955- ). He rose to prominence in the ‘90s with expressive drawings, which he animated in videos. His oeuvre, which covers four decades, has featured different artistic disciplines. For many years, Kentridge has been working successfully on major opera and theater productions. His close relationship with the theater, where he has worked as an actor, producer, set and costume designer, informs his visual art, and vice versa. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind William Kentridge (28/4/1955- ). He rose to prominence in the ‘90s with expressive drawings, which he animated in videos. His oeuvre, which covers four decades, has featured different artistic disciplines. For many years, Kentridge has been working successfully on major opera and theater productions. His close relationship with the theater, where he has worked as an actor, producer, set and costume designer, informs his visual art, and vice versa. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Dimitris Lempesis

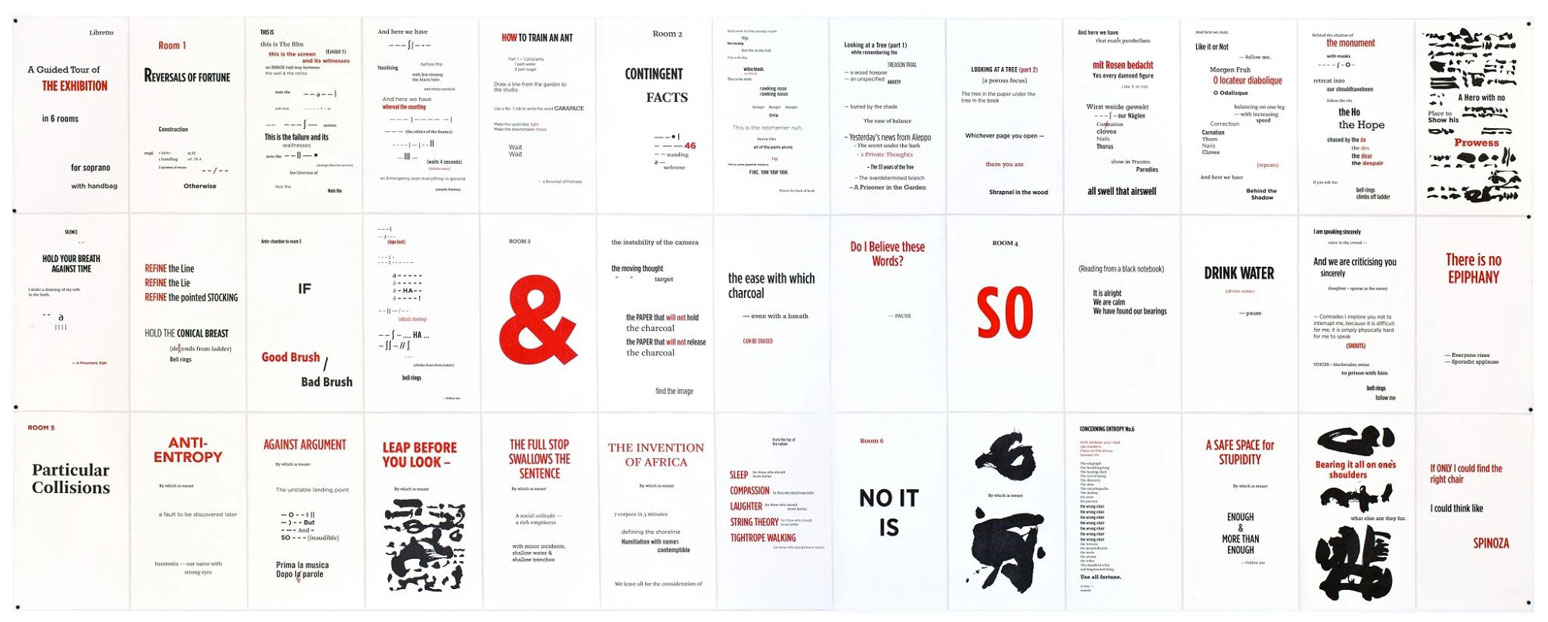

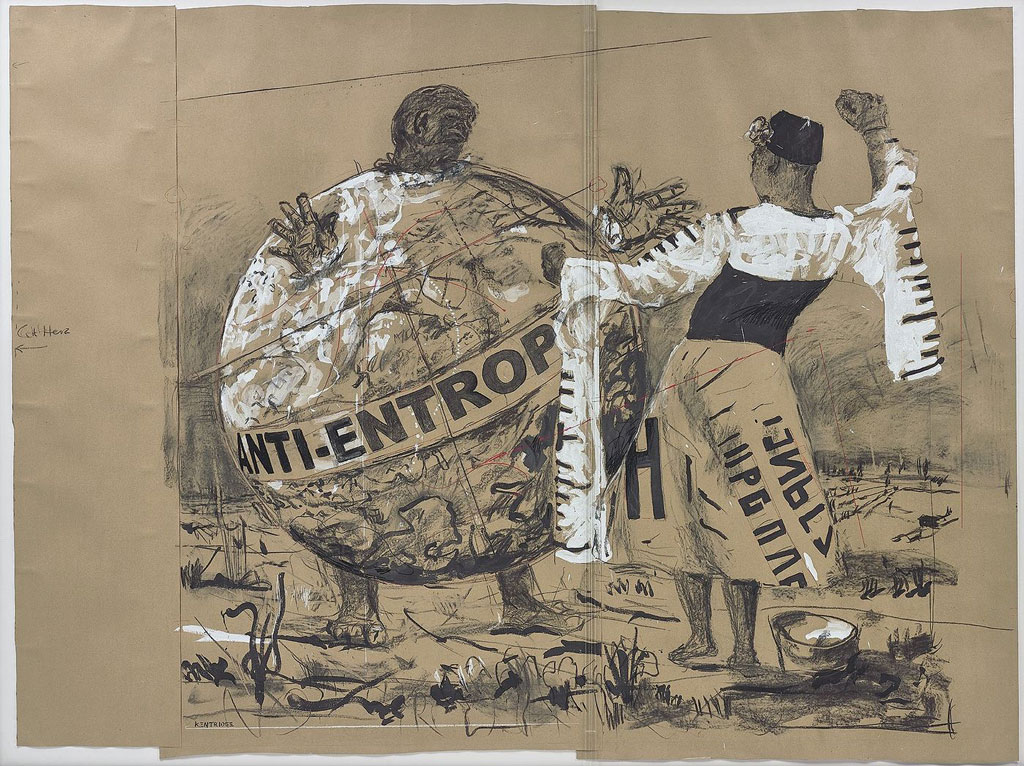

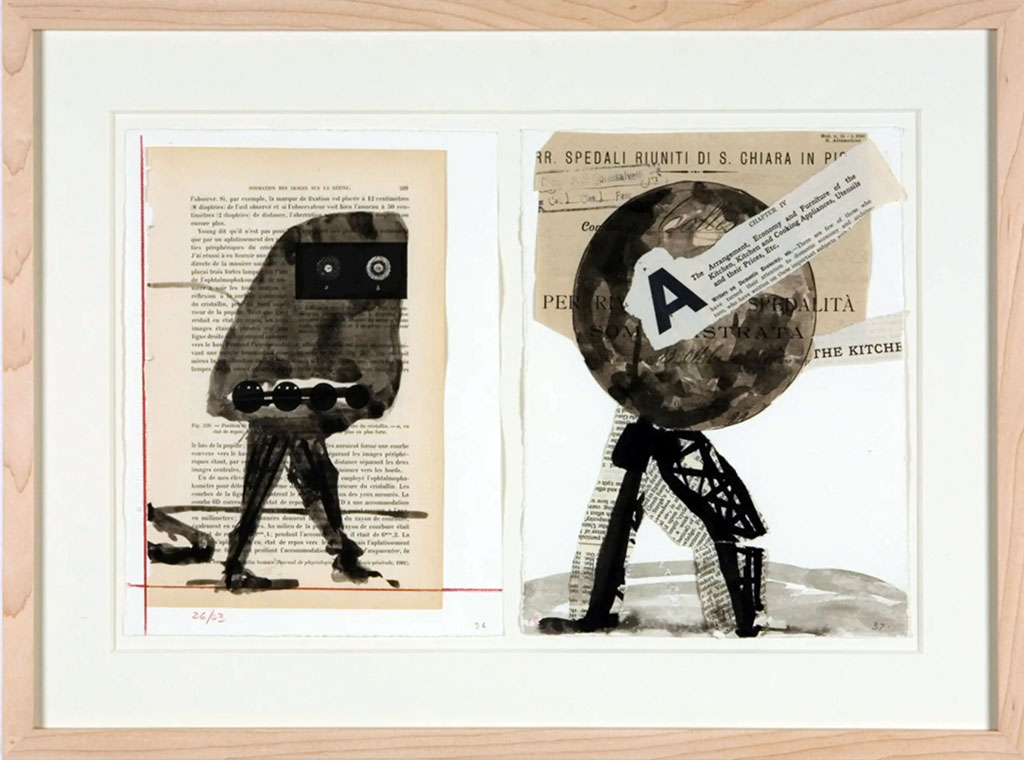

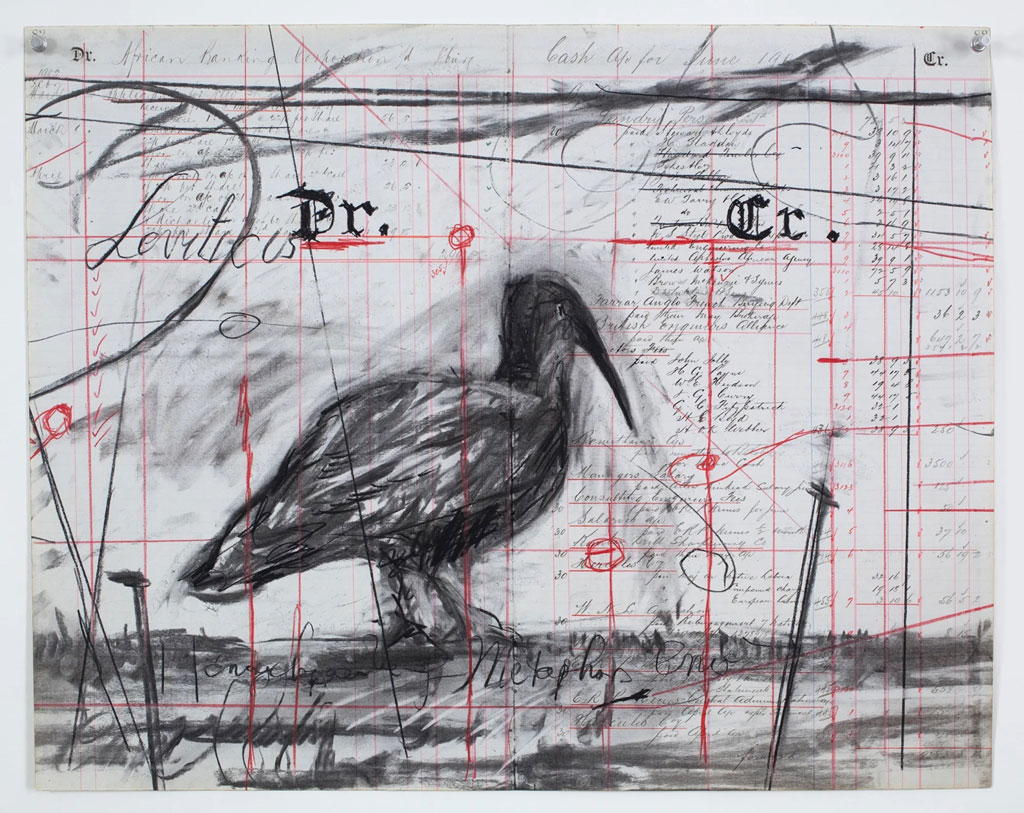

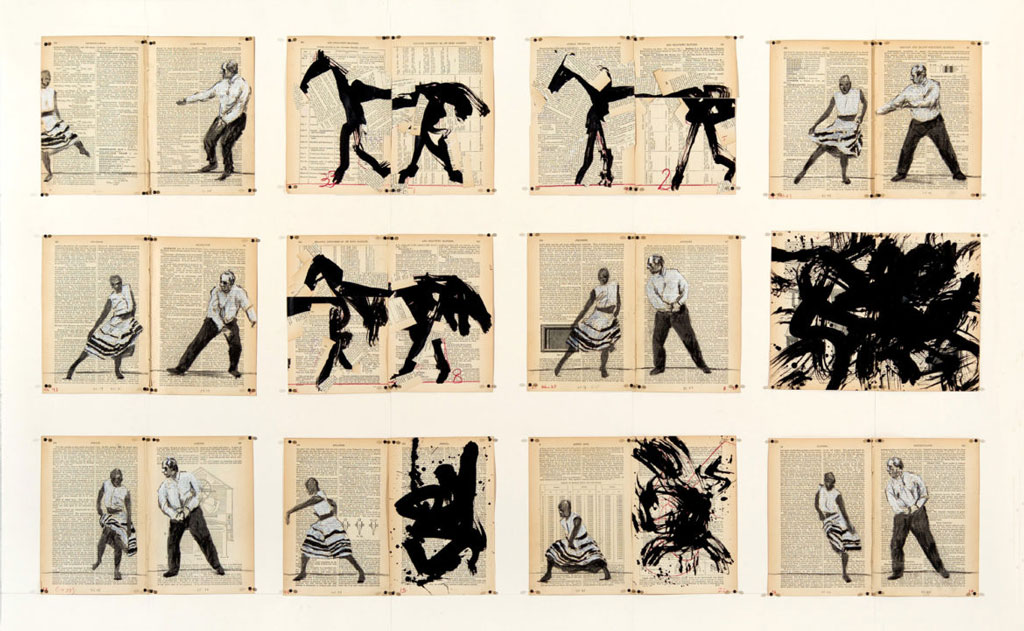

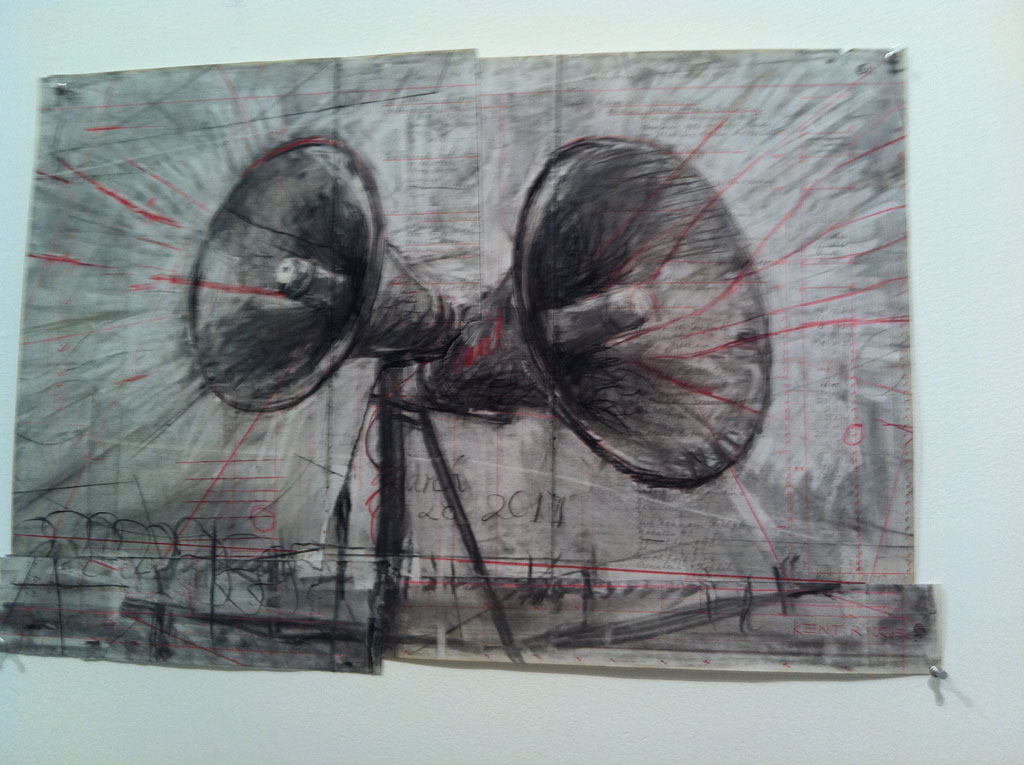

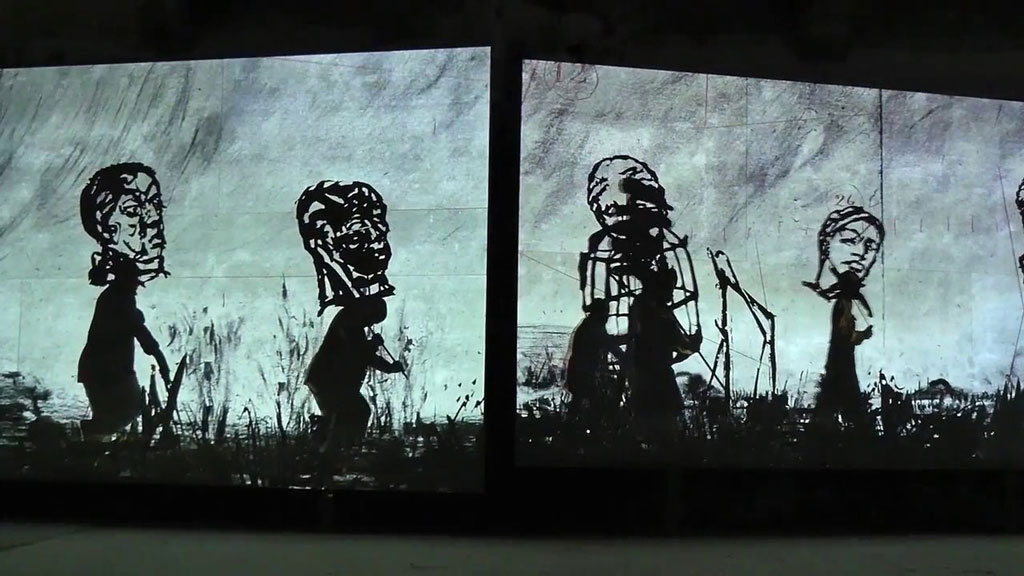

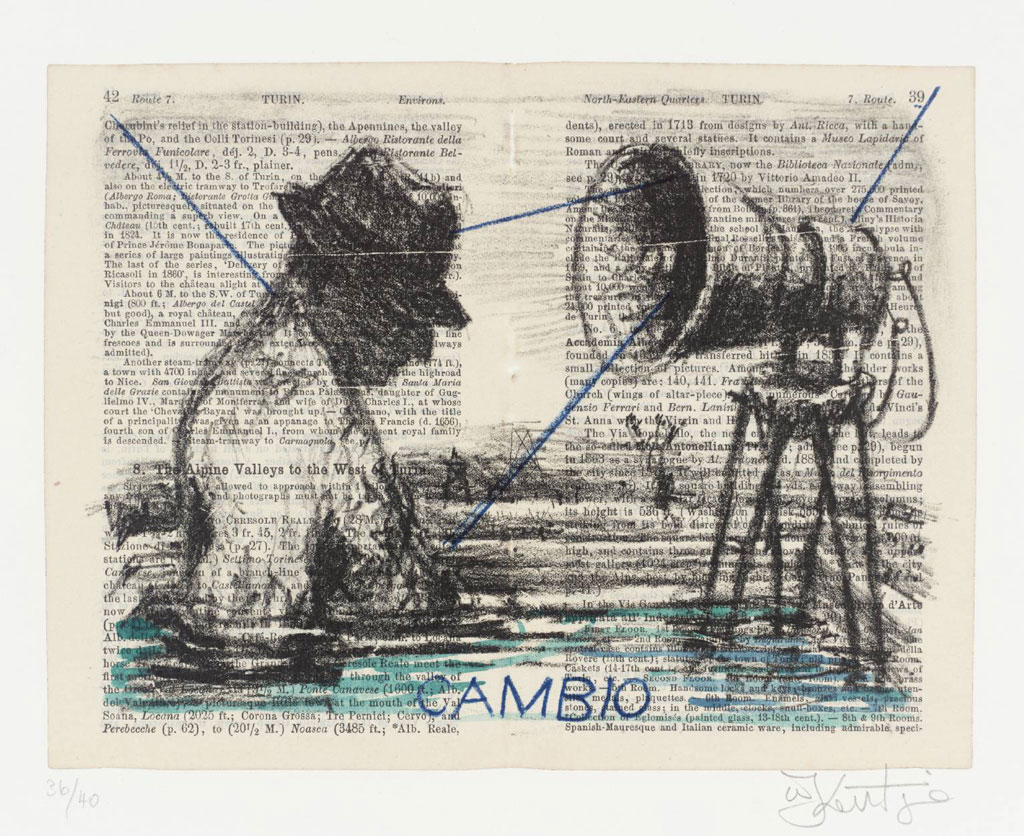

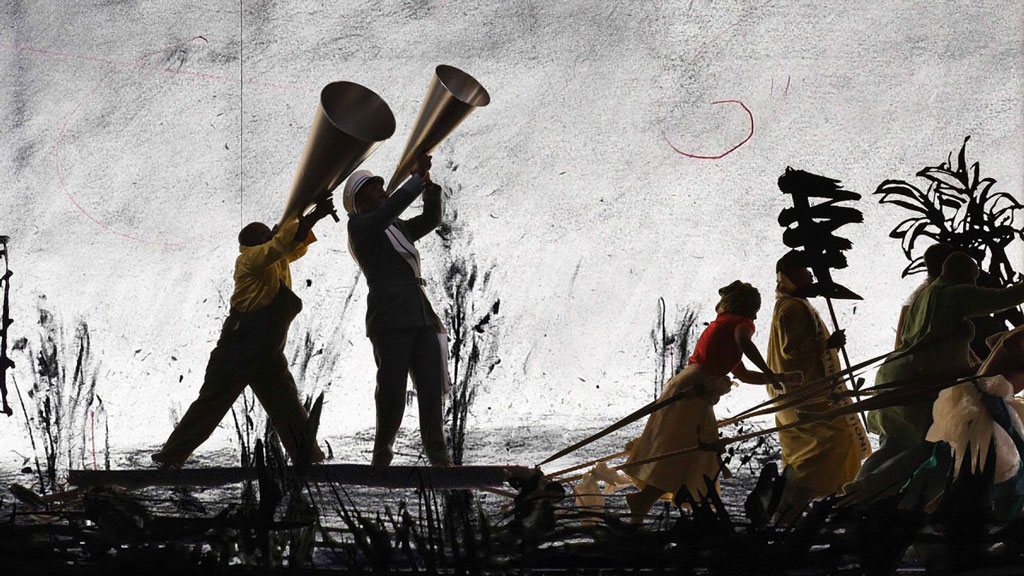

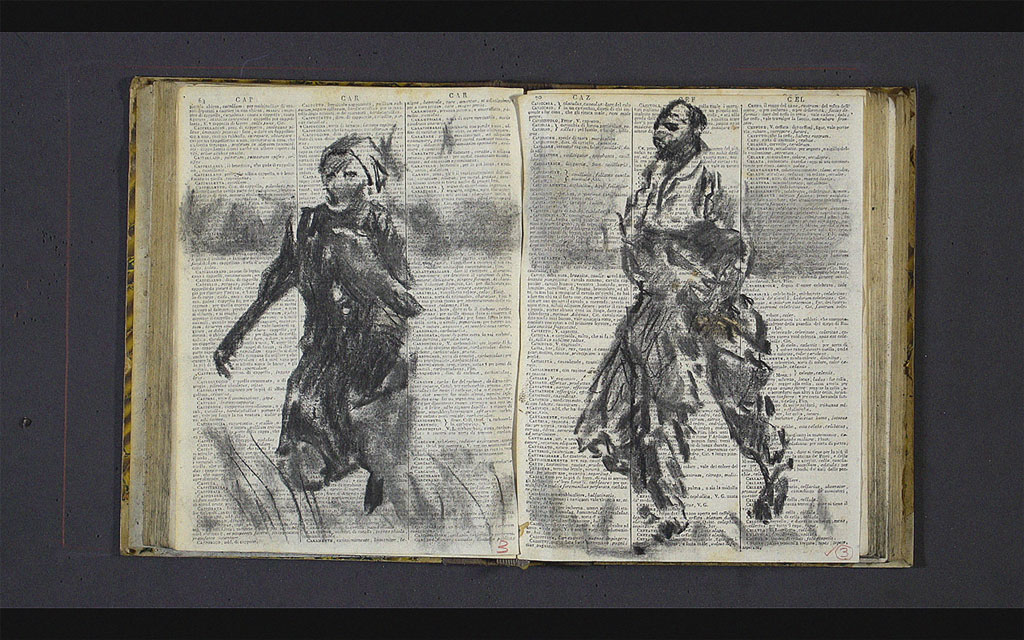

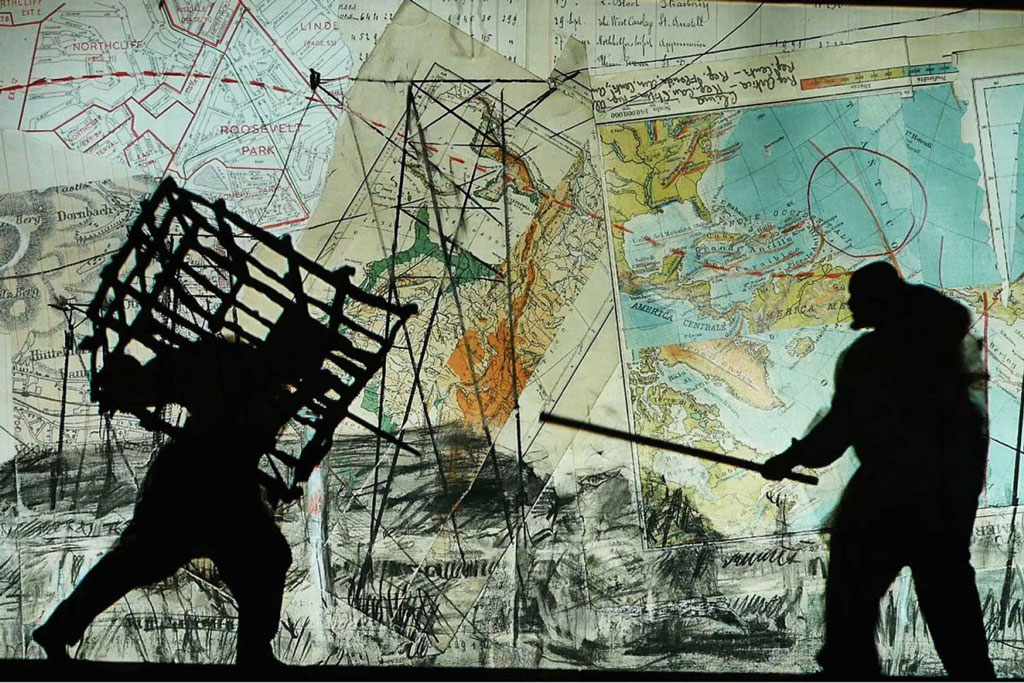

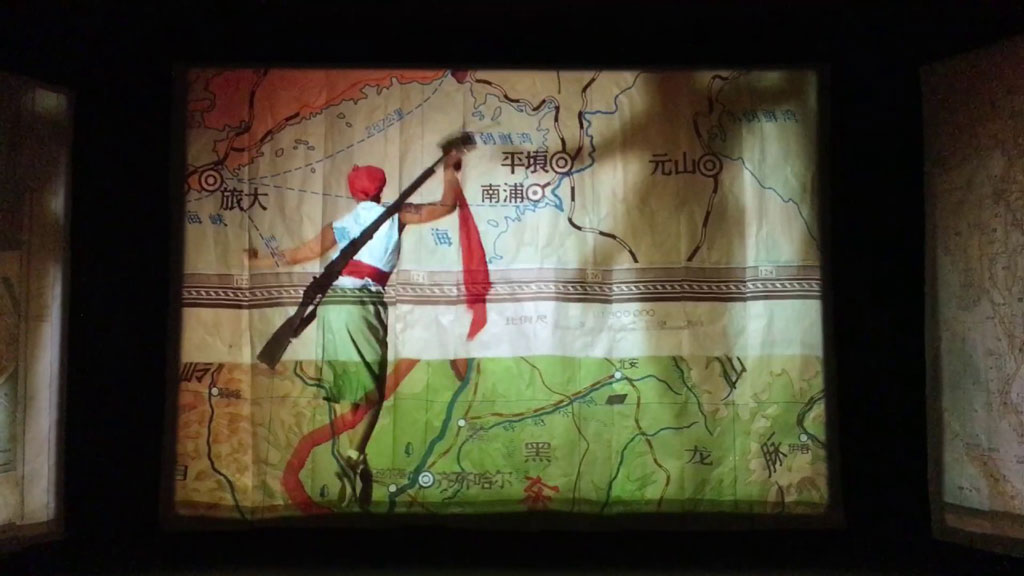

William Kentridge was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1955. His parents were both anti-apartheid lawyers and civil-rights activists, a political backdrop and family lineage important for Kentridge’s future career as an artist. Kentridge earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Politics and African studies at the University of the Witwatersrand, before changing course to study Fine Arts at the Johannesburg Art Foundation, yet the fascination with African history and politics remained with him. At art school he struggled with the traditions of oil on canvas, particularly when painting with color, choosing instead to focus on drawing with charcoal, even though it was generally considered an “ancillary” to painting. After taking an evening class in etching he found a small spark of new hope. By 1981 Kentridge had changed course again, leaving South Africa to study theatre in Paris with the hope of becoming an actor. After a year in Paris, Kentridge discovered he “wasn’t any better at acting than painting” yet his fascination with time, movement, and characters remained, along with a desire to work collaboratively. He returned to South Africa with visions of becoming a filmmaker, working as a props assistant on a television series, yet again he found himself against a brick wall. After going through this process of “early failures”, Kentridge found himself once again looking for a way to be an artist. Throughout this time Kentridge had discovered a natural blend of interests in drawing, film, and performance, which would become the defining, hallmark characteristics of his mature work. Having previously been told that it was important to specialise, that he must decide either to act or to draw, or would otherwise become an amateur, he realised that quite to the contrary it was in a space of cross-fertilisation of genres where he in fact felt at home and could flourish. Kentridge began producing and exhibiting black and white charcoal drawings which demonstrated his ongoing dissatisfaction with the South African apartheid regime in the 1980s, yet he soon felt stifled and frustrated by the material limitations he had set himself. As a way out, he developed a non-traditional animation technique to bring his drawings to life. Instead of creating traditional animations by producing sequential drawings on separate sheets of paper, he began using a single sheet of paper, erasing and redrawing movements in charcoal and photographing the changes before bringing them together as a sequence on screen. Evidence of the erased changes were left behind on the page, a process he initially tried to remove, before realising it could add a visceral, tactile sensibility to his work, and he even began exhibiting the palimpsest-like drawings left behind alongside his films. Forging collaborative partnerships with filmmakers, theatrical companies, and musicians over the years that have followed has allowed Kentridge to expand the breadth and ambition of his film. Kentridge also began collaborating on various projects with the Handspring Puppet Company at this time, creating a series of stage performances including «Woyzeck on the Highveld» (1992), in which both puppets and their manipulators are seen on stage. Kentridge’s career as an artist gradually gained momentum over the following decade as he maintained a multimedia practice, combining elements of drawing, film, and theatre. Much of his work continued to contain political elements, but there is always a more abstract and philosophical approach that works in parallel. In his animated films, some of his fictional characters appear repeatedly, most commonly Soho Eckstein, a hard-nosed capitalist in a pinstriped suit, and his nemesis, the artist and dreamer Felix Teitelbaum, two opposing characters representing the divided fields of apartheid, and also the contradictory forces even at odds within one individual. In 1997, Kentridge showed two films featuring Soho and Felix at Documenta, as at once haunting portrayals of the terrors in apartheid, as well as an examination of identity and the divided forces within the self then reflected outwards. In 2005 Kentridge extended his oeuvre to include opera, producing an alternate version of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” as seen through a contemporary lens for Brussels’ La Monnaie, followed five years later by the production of Dmitri Shostakovich’s satirical stage show, “The Nose” inspired by Nikolai Gogol’s surreal misadventures of a bureaucratic protagonist who goes in search of his missing nose, for New York City’s Metropolitan Opera. His projects became bigger, even more muti-layered, and involved more collaborators. “O Sentimental Machine” (2015), originally commissioned for 14th Istanbul Biennial, where it was installed in Hotel Splendid Palas. In a critique of Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky’s notion that people are “Sentimental but programmable machines”, subtitled videos of speeches by Trotsky and also his time in exile in Istanbul are projected on to glass doors on either side of the installation, offering the viewer the opportunity to observe what is going on behind the closed doors.

William Kentridge was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1955. His parents were both anti-apartheid lawyers and civil-rights activists, a political backdrop and family lineage important for Kentridge’s future career as an artist. Kentridge earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Politics and African studies at the University of the Witwatersrand, before changing course to study Fine Arts at the Johannesburg Art Foundation, yet the fascination with African history and politics remained with him. At art school he struggled with the traditions of oil on canvas, particularly when painting with color, choosing instead to focus on drawing with charcoal, even though it was generally considered an “ancillary” to painting. After taking an evening class in etching he found a small spark of new hope. By 1981 Kentridge had changed course again, leaving South Africa to study theatre in Paris with the hope of becoming an actor. After a year in Paris, Kentridge discovered he “wasn’t any better at acting than painting” yet his fascination with time, movement, and characters remained, along with a desire to work collaboratively. He returned to South Africa with visions of becoming a filmmaker, working as a props assistant on a television series, yet again he found himself against a brick wall. After going through this process of “early failures”, Kentridge found himself once again looking for a way to be an artist. Throughout this time Kentridge had discovered a natural blend of interests in drawing, film, and performance, which would become the defining, hallmark characteristics of his mature work. Having previously been told that it was important to specialise, that he must decide either to act or to draw, or would otherwise become an amateur, he realised that quite to the contrary it was in a space of cross-fertilisation of genres where he in fact felt at home and could flourish. Kentridge began producing and exhibiting black and white charcoal drawings which demonstrated his ongoing dissatisfaction with the South African apartheid regime in the 1980s, yet he soon felt stifled and frustrated by the material limitations he had set himself. As a way out, he developed a non-traditional animation technique to bring his drawings to life. Instead of creating traditional animations by producing sequential drawings on separate sheets of paper, he began using a single sheet of paper, erasing and redrawing movements in charcoal and photographing the changes before bringing them together as a sequence on screen. Evidence of the erased changes were left behind on the page, a process he initially tried to remove, before realising it could add a visceral, tactile sensibility to his work, and he even began exhibiting the palimpsest-like drawings left behind alongside his films. Forging collaborative partnerships with filmmakers, theatrical companies, and musicians over the years that have followed has allowed Kentridge to expand the breadth and ambition of his film. Kentridge also began collaborating on various projects with the Handspring Puppet Company at this time, creating a series of stage performances including «Woyzeck on the Highveld» (1992), in which both puppets and their manipulators are seen on stage. Kentridge’s career as an artist gradually gained momentum over the following decade as he maintained a multimedia practice, combining elements of drawing, film, and theatre. Much of his work continued to contain political elements, but there is always a more abstract and philosophical approach that works in parallel. In his animated films, some of his fictional characters appear repeatedly, most commonly Soho Eckstein, a hard-nosed capitalist in a pinstriped suit, and his nemesis, the artist and dreamer Felix Teitelbaum, two opposing characters representing the divided fields of apartheid, and also the contradictory forces even at odds within one individual. In 1997, Kentridge showed two films featuring Soho and Felix at Documenta, as at once haunting portrayals of the terrors in apartheid, as well as an examination of identity and the divided forces within the self then reflected outwards. In 2005 Kentridge extended his oeuvre to include opera, producing an alternate version of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” as seen through a contemporary lens for Brussels’ La Monnaie, followed five years later by the production of Dmitri Shostakovich’s satirical stage show, “The Nose” inspired by Nikolai Gogol’s surreal misadventures of a bureaucratic protagonist who goes in search of his missing nose, for New York City’s Metropolitan Opera. His projects became bigger, even more muti-layered, and involved more collaborators. “O Sentimental Machine” (2015), originally commissioned for 14th Istanbul Biennial, where it was installed in Hotel Splendid Palas. In a critique of Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky’s notion that people are “Sentimental but programmable machines”, subtitled videos of speeches by Trotsky and also his time in exile in Istanbul are projected on to glass doors on either side of the installation, offering the viewer the opportunity to observe what is going on behind the closed doors.