ART-TRIBUTE:Weaving and other Practices… Faith Ringgold

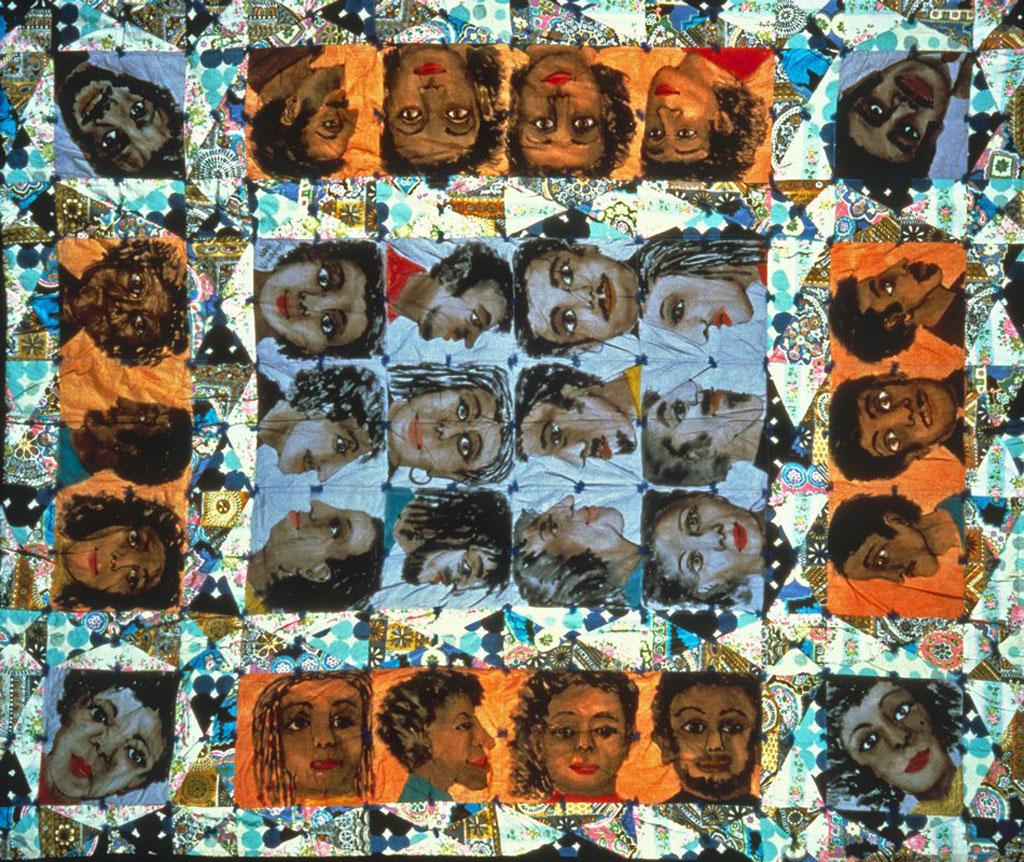

We continue our Tribute with the American artist Faith Ringgold (8/10/1930- ), she took the traditional craft of quilt making, which has its roots in the slave culture of the South pre-civil war era and re-interpreted its function to tell stories of her life and those of others in the black community. As a social activist, she has used art to start and grow such organizations that support African American women artists.

We continue our Tribute with the American artist Faith Ringgold (8/10/1930- ), she took the traditional craft of quilt making, which has its roots in the slave culture of the South pre-civil war era and re-interpreted its function to tell stories of her life and those of others in the black community. As a social activist, she has used art to start and grow such organizations that support African American women artists.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Faith Ringgold grew up in Harlem during the Great Depression. Often unable to attend school due to asthma, Ringgold was encouraged in her artistic pursuits by her mother who also taught her how to sew and use patterns. Her grandmother taught Ringgold quilting and the importance of the African-American tradition in telling stories, conveying messages, and creating community. In 1950, intending to study art, Ringgold enrolled at New York’s City College but, because art was then believed to be an exclusively male profession, she was required to enroll in art education in order to study art. Ringgold graduated in 1955 with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art and Education. After graduation Ringgold began teaching in the public school system in New York and began working toward a Master of Fine Arts degree at City College. Earning her degree in 1959. Finding it difficult as an African American woman artist to find gallery representation for her work, Ringgold had a meeting with Ruth White who ran a gallery in NY in 1963 that proved life changing. White, examining Ringgold’s paintings of still lifes and landscapes, told her she could not show her works. In the early 1960s, she began painting the “American People” Series. In 1967 an invitation from Robert Newman for a solo show at his co-op gallery Spectrum gave new impetus to the work. She followed with the “Black Light” Series. At the same time, Ringgold became an activist for feminist and anti-racism causes. She cofounded the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee with art critic and historian Lucy Lippard and artist Poppy Johnson to protest an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1968. No women, and no African American artists were included in the show. To protest, the group left eggs in the Whitney, and Ringgold came up with the idea of each member blowing a whistle to disrupt the show. Subsequently, Ringgold cofounded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, the National Black Feminist Organization, and “Where We At” Black Women Artists. In the early 1970s, she painted a mural For the Women’s House as a permanent installation at the Women’s House of Detention on Riker’s Island. As a result, Art Without Walls, an organization that brings art to prison populations, was founded. In the early 1970s Ringgold’s work moved away from traditional painting as she began using fabric and experimenting with soft sculpture. Influenced by the traditional Western African use of masks, she created costumes by painting linen canvas to which she added beads, raffia hair, and painted gourds for breasts. Each work represented a character, as she said that she wanted each mask to represent a “spiritual and sculptural identity”. As she intended the pieces in her “Witch Mask” Series to be worn, not displayed merely as art objects, she developed her first performance piece, “The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro” a narrative that dealt with the affects of slavery and drug addiction in the African American community. Ringgold’s “Family of Woman Mask” Series continued her work in mask costumes, while also including her life size portrait soft sculpture of NBA basketball playerWilt Chamberlain, who had made negative comments about African American women. In 1972 on a visit to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, Ringgold saw an exhibit of thangkas, Buddhist paintings on cloth scrolls, and was inspired to add fabric borders to her paintings as in her “Slave Rape” Series of 1983, which focused on the slave trade viewed from the experience of an African woman taken into slavery. Ringgold also drew upon the African American tradition of quilt making, and in 1980, working with her mother, created “Echoes of Harlem”, which depicted 30 local residents. Quilts allowed Ringgold to tell stories by combining images with handwritten texts. In 1980’s Ringgold continued to develop images that questioned European art and culture from an African American perspective. In her series, “The French Collection”, Ringgold depicts European modernism and its seminal figures from the viewpoint of a fictitious character, a remarkable young African American woman who wants to be an artist. Ringgold’s style continued to evolve as she incorporated elements from contemporary art movements while simultaneously adopting new techniques into her fabric work. In the 1990’s Ringgold’s style was influenced by the colors and repetitive imagery of Abstract Expressionism and Pop art, and she began using applique, with fabric sewn onto the canvas, and photo-etching. In 2000 she began to use silkscreen printing on pieces that use text and borders of fabric. In 2014 she created the billboard “Groovin High” as an installation piece for the High Line’s train stop at 18th Street and 10th Avenue. Many of her later works are based upon her earlier story quilts.

Faith Ringgold grew up in Harlem during the Great Depression. Often unable to attend school due to asthma, Ringgold was encouraged in her artistic pursuits by her mother who also taught her how to sew and use patterns. Her grandmother taught Ringgold quilting and the importance of the African-American tradition in telling stories, conveying messages, and creating community. In 1950, intending to study art, Ringgold enrolled at New York’s City College but, because art was then believed to be an exclusively male profession, she was required to enroll in art education in order to study art. Ringgold graduated in 1955 with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art and Education. After graduation Ringgold began teaching in the public school system in New York and began working toward a Master of Fine Arts degree at City College. Earning her degree in 1959. Finding it difficult as an African American woman artist to find gallery representation for her work, Ringgold had a meeting with Ruth White who ran a gallery in NY in 1963 that proved life changing. White, examining Ringgold’s paintings of still lifes and landscapes, told her she could not show her works. In the early 1960s, she began painting the “American People” Series. In 1967 an invitation from Robert Newman for a solo show at his co-op gallery Spectrum gave new impetus to the work. She followed with the “Black Light” Series. At the same time, Ringgold became an activist for feminist and anti-racism causes. She cofounded the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee with art critic and historian Lucy Lippard and artist Poppy Johnson to protest an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1968. No women, and no African American artists were included in the show. To protest, the group left eggs in the Whitney, and Ringgold came up with the idea of each member blowing a whistle to disrupt the show. Subsequently, Ringgold cofounded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, the National Black Feminist Organization, and “Where We At” Black Women Artists. In the early 1970s, she painted a mural For the Women’s House as a permanent installation at the Women’s House of Detention on Riker’s Island. As a result, Art Without Walls, an organization that brings art to prison populations, was founded. In the early 1970s Ringgold’s work moved away from traditional painting as she began using fabric and experimenting with soft sculpture. Influenced by the traditional Western African use of masks, she created costumes by painting linen canvas to which she added beads, raffia hair, and painted gourds for breasts. Each work represented a character, as she said that she wanted each mask to represent a “spiritual and sculptural identity”. As she intended the pieces in her “Witch Mask” Series to be worn, not displayed merely as art objects, she developed her first performance piece, “The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro” a narrative that dealt with the affects of slavery and drug addiction in the African American community. Ringgold’s “Family of Woman Mask” Series continued her work in mask costumes, while also including her life size portrait soft sculpture of NBA basketball playerWilt Chamberlain, who had made negative comments about African American women. In 1972 on a visit to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, Ringgold saw an exhibit of thangkas, Buddhist paintings on cloth scrolls, and was inspired to add fabric borders to her paintings as in her “Slave Rape” Series of 1983, which focused on the slave trade viewed from the experience of an African woman taken into slavery. Ringgold also drew upon the African American tradition of quilt making, and in 1980, working with her mother, created “Echoes of Harlem”, which depicted 30 local residents. Quilts allowed Ringgold to tell stories by combining images with handwritten texts. In 1980’s Ringgold continued to develop images that questioned European art and culture from an African American perspective. In her series, “The French Collection”, Ringgold depicts European modernism and its seminal figures from the viewpoint of a fictitious character, a remarkable young African American woman who wants to be an artist. Ringgold’s style continued to evolve as she incorporated elements from contemporary art movements while simultaneously adopting new techniques into her fabric work. In the 1990’s Ringgold’s style was influenced by the colors and repetitive imagery of Abstract Expressionism and Pop art, and she began using applique, with fabric sewn onto the canvas, and photo-etching. In 2000 she began to use silkscreen printing on pieces that use text and borders of fabric. In 2014 she created the billboard “Groovin High” as an installation piece for the High Line’s train stop at 18th Street and 10th Avenue. Many of her later works are based upon her earlier story quilts.