ART-TRIBUTE:Weaving and other Practices… Mrinalini Mukherjee

We continue our Tribute with Mrinalini Mukherjee, she hailed from a different art world, India in the 1970s to the 2000s, and her work draws on a pool of references and traditions that might be slightly unfamiliar. But at the same time, her sculptures eschewed the kinds of easily marketed images of “Indian-ness” that the global contemporary art biz sometimes feeds on. It has its own rhythms, and you can’t approach it either purely formally or purely iconographically, but have to find some other way in.

We continue our Tribute with Mrinalini Mukherjee, she hailed from a different art world, India in the 1970s to the 2000s, and her work draws on a pool of references and traditions that might be slightly unfamiliar. But at the same time, her sculptures eschewed the kinds of easily marketed images of “Indian-ness” that the global contemporary art biz sometimes feeds on. It has its own rhythms, and you can’t approach it either purely formally or purely iconographically, but have to find some other way in.

By Efi Michalarou

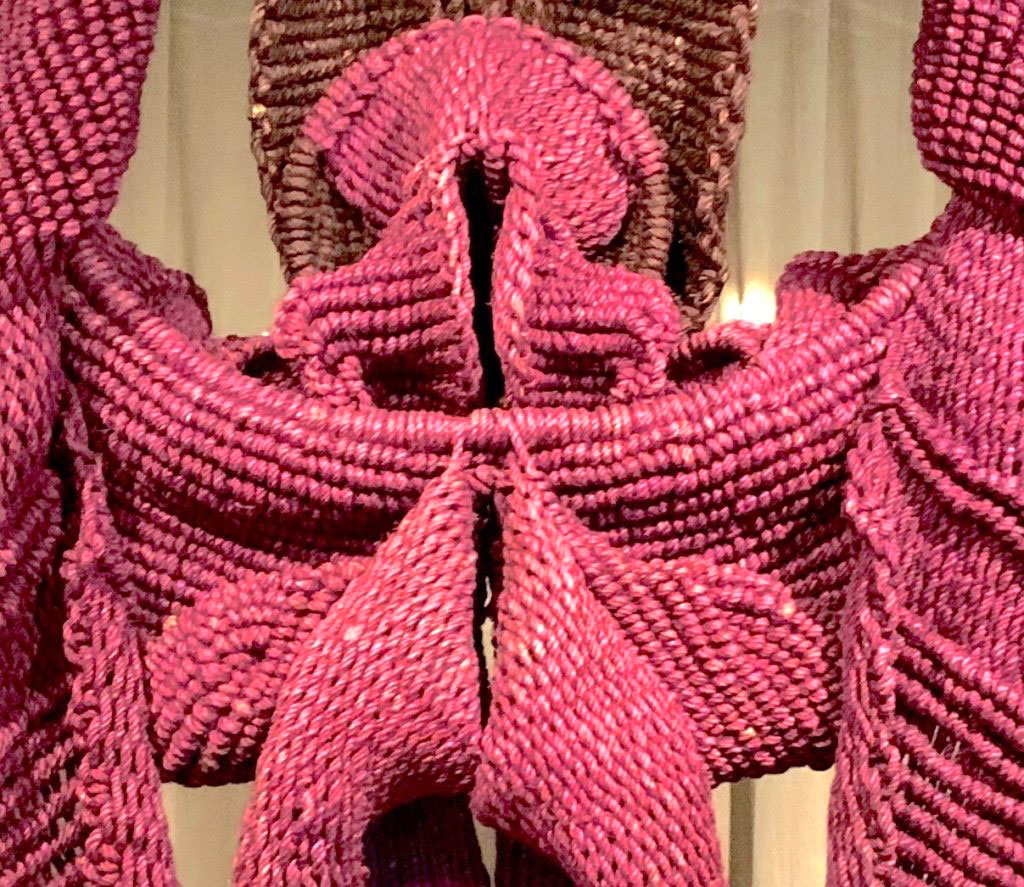

Born in Mumbai in 1949, and raised in the northern city of Dehradun, Mrinalini Mukherjee was the only daughter of Indian artists Benode Behari and Leela Mukherjee. By age 21, Mrinalini had earned a degree in painting from the MS University of Baroda, near Mumbai, and a postgraduate diploma in mural design under KG Subramanyan. In 1971, a British Council scholarship sent the imaginative young sculptor to the West Surrey College of Art and Design in the United Kingdom, where she pursued her tied-fiber works and began to gain notice. But it was in New Delhi, to which she returned and spent the remaining decades of her career, that her practice bloomed. Mukherjee’s first solo exhibition, which was held at Shridharani Art Gallery in 1972, featured warped, woven forms in dyed natural fibers—a series of works for which she was gaining a reputation. Named after deities of fertility, the crudely shaped, anthropomorphic pieces were seen as sensual and suggestive. Additional group and solo exhibitions then followed, and Mukherjee’s practice later evolved to include hand-modeled ceramic pieces evoking similar forms. In 1994, Mukherjee received an invitation to exhibit at the Modern Art Oxford (then the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford). The prestigious UK gallery, under the leadership of David Elliott, mounted an exhibition of Mukherjee’s sculptures, putting her in the ranks of Marina Abramović and Donald Judd, who exhibited there a year later. In an interview for the exhibition, Mukherjee told curator Chrissies Iles, “My mythology is de-conventionalised and personal, as indeed are my methods and materials . . . My idea of the sacred is not rooted in any specific culture. To me it is a feeling that I may get in a church, mosque, temple, or forest . . . My inspiration and visual stimuli come from all over the world, from museum objects and artifacts and more immediately from my environment”. The following year, in a 1996 issue of “ArtAsiaPacific”, art historian and indepenent curator Deepak Ananth observed that Mukherjee’s predilection for modest, earthly materials aligned with the practices of her early professor, KG Subramanyan, who encouraged his students to take inspiration from India’s rich history of artisanal craft. In his article, entitled “The Knots are Many But the Thread is One,” Ananth wrote: “As if in harmony with the vegetal realm from which her medium is derived, the leading metaphor of Mukherjee’s work comes from the organic life of plants. Improvising upon a motif or image that serves as her starting point the work’s gradual unfolding itself becomes analogous to the stirring into maturation of a sapling”. In the early 2000s, Mukherjee’s roving journey through various materials led her to bronze. Experimenting with the lost-wax casting technique, she produced folded, layered and marked works with the organic forms for which she had become known.

Born in Mumbai in 1949, and raised in the northern city of Dehradun, Mrinalini Mukherjee was the only daughter of Indian artists Benode Behari and Leela Mukherjee. By age 21, Mrinalini had earned a degree in painting from the MS University of Baroda, near Mumbai, and a postgraduate diploma in mural design under KG Subramanyan. In 1971, a British Council scholarship sent the imaginative young sculptor to the West Surrey College of Art and Design in the United Kingdom, where she pursued her tied-fiber works and began to gain notice. But it was in New Delhi, to which she returned and spent the remaining decades of her career, that her practice bloomed. Mukherjee’s first solo exhibition, which was held at Shridharani Art Gallery in 1972, featured warped, woven forms in dyed natural fibers—a series of works for which she was gaining a reputation. Named after deities of fertility, the crudely shaped, anthropomorphic pieces were seen as sensual and suggestive. Additional group and solo exhibitions then followed, and Mukherjee’s practice later evolved to include hand-modeled ceramic pieces evoking similar forms. In 1994, Mukherjee received an invitation to exhibit at the Modern Art Oxford (then the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford). The prestigious UK gallery, under the leadership of David Elliott, mounted an exhibition of Mukherjee’s sculptures, putting her in the ranks of Marina Abramović and Donald Judd, who exhibited there a year later. In an interview for the exhibition, Mukherjee told curator Chrissies Iles, “My mythology is de-conventionalised and personal, as indeed are my methods and materials . . . My idea of the sacred is not rooted in any specific culture. To me it is a feeling that I may get in a church, mosque, temple, or forest . . . My inspiration and visual stimuli come from all over the world, from museum objects and artifacts and more immediately from my environment”. The following year, in a 1996 issue of “ArtAsiaPacific”, art historian and indepenent curator Deepak Ananth observed that Mukherjee’s predilection for modest, earthly materials aligned with the practices of her early professor, KG Subramanyan, who encouraged his students to take inspiration from India’s rich history of artisanal craft. In his article, entitled “The Knots are Many But the Thread is One,” Ananth wrote: “As if in harmony with the vegetal realm from which her medium is derived, the leading metaphor of Mukherjee’s work comes from the organic life of plants. Improvising upon a motif or image that serves as her starting point the work’s gradual unfolding itself becomes analogous to the stirring into maturation of a sapling”. In the early 2000s, Mukherjee’s roving journey through various materials led her to bronze. Experimenting with the lost-wax casting technique, she produced folded, layered and marked works with the organic forms for which she had become known.