ART-TRIBUTE:Weaving and other Practices…Sheela Gowda

We continue our Tribute with Sheela Gowda (1957- ), an artist living and working in Bangalore, India on the occasion of her digital exhibition “It.. Matters”. Sheela Gowda began painting in her early career but started to make three-dimensional work in the 1990s in reaction to the rapid progress of economic and cultural development in India.

We continue our Tribute with Sheela Gowda (1957- ), an artist living and working in Bangalore, India on the occasion of her digital exhibition “It.. Matters”. Sheela Gowda began painting in her early career but started to make three-dimensional work in the 1990s in reaction to the rapid progress of economic and cultural development in India.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Lenbachhaus Munich Archive

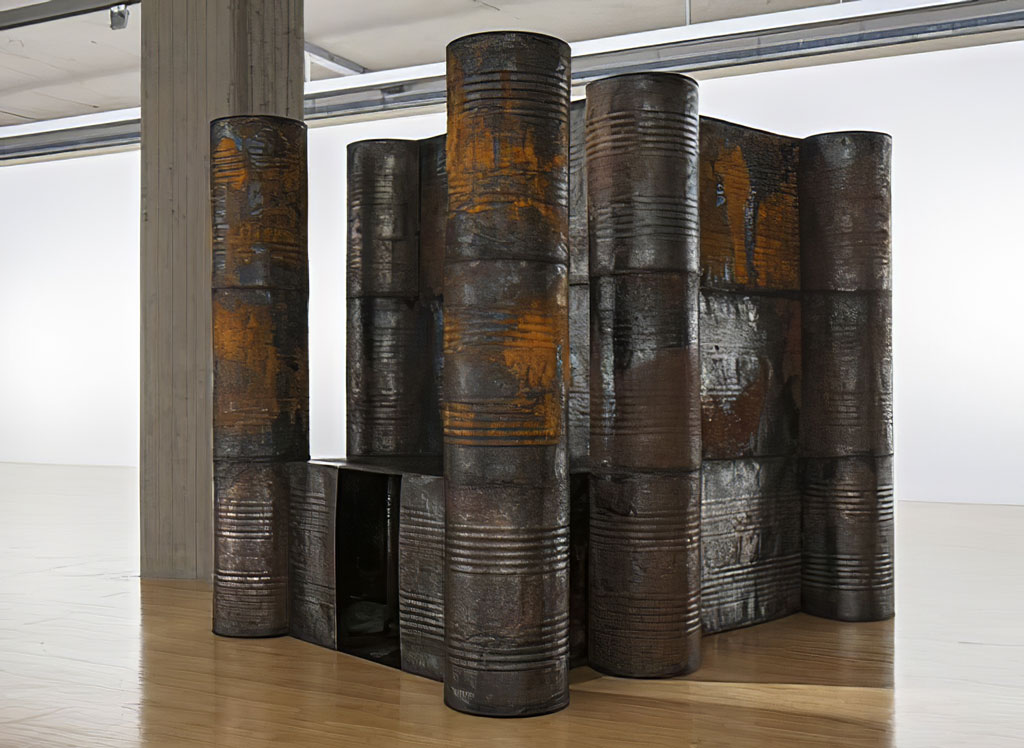

For Sheela Gowda the transformative ritual that occurs during a highly performance-based process of manipulation, confrontation and conversation with her materials, remains fundamental. Sheela Gowda redefines the pathos of things, their feelings and affections; a relational condition between objects, their reasons for being and their behaviors. It is a “moment of encounter,” understood not as a moment in time but as a kind of force that allows a particular set of circumstances to come together. Sheela Gowda initially trained in painting at the Ken School of Art, Bangalore, at M.S. University, Baroda, and at Visva-Bharati University at Santiniketan. At that time, these academic contexts were shaped by a remarkable Indian modernist tradition, along with a contemporary interpretation of classical Indian art and an interest in vernacular, popular imagery and craft traditions. Returning from London in the mid-1980s after completing her postgraduate studies at the Royal College of Art, Gowda started her transition from the pictorial space to three-dimensional works, definitively breaking the “frame” within her practice. For her installations, Gowda uses distinctive materials from her country whose nature, colors, and scents endow her works with a narrative as well as metaphorical force. The creative use of cow dung, kumkum powder, coconut fiber, hair, needles, threads, stones, tar barrels, or tarpaulins blends connotations of manual craftsmanship and practical application with poetic intensity for a meditation on both urban and rural life in India. “Behold” (2009) consists of 4000 meters of hand-twisted rope made of human hair and 20 car bumpers, individually or in sets, suspended in front of the wall by the hair ropes. As always in Sheela Gowda’s art, the materials and their employment tell stories both about cultic and spiritual practices and about the economic and functional benefits extracted from them. Her installations and the stuff they are made of invariably tie in with social issues and labor conditions as well as the shift from traditional craftsman-ship to industrial processing. When a vow taken to the gods has been fulfilled, faithful Hindus traditionally have their hair shorn as an offering or sacrifice before entering the temple of the god or goddess they have taken the vow to. Piles of hair are collected at such pilgrimages. These short strands of hair measuring around 2 to 3 cm are woven into 3 meter ropes that are tied to the bumpers of cars and buses as talismans, to ward off accidents and misfortune for the passengers. Unknown to the believers, longer hair collected from pilgrims is fed into a different cycle, one that serves the economic interests of the beauty industry. In a factory near Gowda’s home city of Bengaluru, women laborers manually prepare it for sale to the West: they wash and dry it, sort it by length, and package it in bundles. It is then shipped by air to Italy, where it is bleached, dyed in the various hues the market demands, and dispatched to destinations all over the world for use in hair extensions and wigs. “Behold” was originally created for the Corderie dell’Arsenale in Venice, the ropeyards where, in the 15th Century the cables were made for the Venetian merchant vessels and warships that plied the Mediterranean Sea. For “Darkroom” (2006), Gowda collected used tar drums from road construction teams to build a shanty fort. Despite the rusted patina of the repurposed metal, the small but well-designed structure, complete with columns, evokes a classical grandeur. Once inside the cramped interior, the viewer is treated to a representation of a starry sky in the form of a ceiling pricked with holes. Thus the work fuses confinement and limitlessness. In the case of the latter, the artist substitutes an illusion of the cosmos, which is not to discount the spurious value of the fake, but to emphasize the power of imagination. From domestic labor to public works, Gowda reflects on internal contradictions: home can be both secure and oppressive, tradition can be inspirational and restraining, industriousness can be innovative and destructive.

“And…” (2007) is the second version of the work “And Tell Him of My Pain” (1998). It was produced for documenta 12 in 2007 and first exhibited there. Sheela Gowda threaded 300 meters of string through 108 needles which when doubled up make 150 meters of strings with the needle bunched up at one end. Coiled and coated with a paste made of kumkum* pigment and glue, the strands form a delicate rope, which the artist arranges in an expansive site-specific installation in the gallery. As in many of her works, she adapts facets of local Indian life and culture such as the ritual use of certain spices or the thread as part of traditional women‘s crafts . In the early 1990s, Sheela Gowda, dissatisfied with figural oil painting, sought to develop new creative means that would better fit what she intended to say with her art. Cow dung proved the suitable material for her endeavor. She first used it as she had used paint, brushing it on paper and jute. Her earliest three “cow dung paintings” from 1992 are on view in this exhibition. She subsequently extended the use of dung into the third dimension: :Untitled (Cow dung)” (1992-2012) is one of the earliest of the installations that resulted. The dung of the cow is a staple of life in rural India and collected for a wide variety of purposes both practical and ritual. Dried cowpats fuel hearths. Malleable moist excrement is used as a building material and applied to walls or floors as a compacting layer. The smoke from smoldering dung repels mosquitoes, and mixed with the leaves of the neem tree, it acts as an antiseptic. Rich in minerals, it is added to compost heaps and spread over fields as fertilizer. Artisans even fashion traditional toys out of it. Yet cow dung has a cultic and spiritual function as well: The entrances to homes are cleaned with water and cow dung on a daily basis and then adorned with rice-flour patterns that are considered auspicious. A blend of dung and ghee (clarified cow milk butter) burns in sacred fires that purify their surroundings. Dung is also one component in the incense powder that is pressed into sticks for ritual use in temples. Most of the work involving cow manure is conventionally performed by women. “Untitled (Cow dung)” consists of nine hundred pats whose diameter is the length of a hand and twenty-five bricks for which the artist compacted several layers to form solid blocks of cow dung. “Someplace” (2005) made of off-the-shelf metal plumbing pipes of varying lengths is a sprawling grid rising off the ground to different heights and forming a continuous loop. The installation’s spread and shape are adapted to the setting whenever the work is displayed in an exhibition. Approaching one of the open pipe ends and pressing an ear to it, the visitors can overhear a monologue by the Indian radio talk show host A.S. Murthy channeled through the metal plumbing. The need to stoop makes the act of hearing and listening visible to others and lends it an almost performative quality. Speaking Kannada (one of India’s regional languages and Sheela Gowda’s mother tongue) Murthy is discussing various political, social and domestic concerns. Gowda heard this monologue on an old radio set she had inherited from her father.

* Kumkum is a powder used for social and religious markings in India. It is made from turmeric or any other local materials. The turmeric is dried and powdered with a bit of slaked lime, which turns the rich yellow powder into a red color.

Info: Lenbachhaus Munich, Luisenstraße 33, Munich, Duration: 31/3-26/7/20, www.lenbachhaus.de

Lenbachhaus Munich is temporarily closed until April 19, 2020 due to the situation with the new coronavirus.