ART-PRESENTATION: Forrest Bess

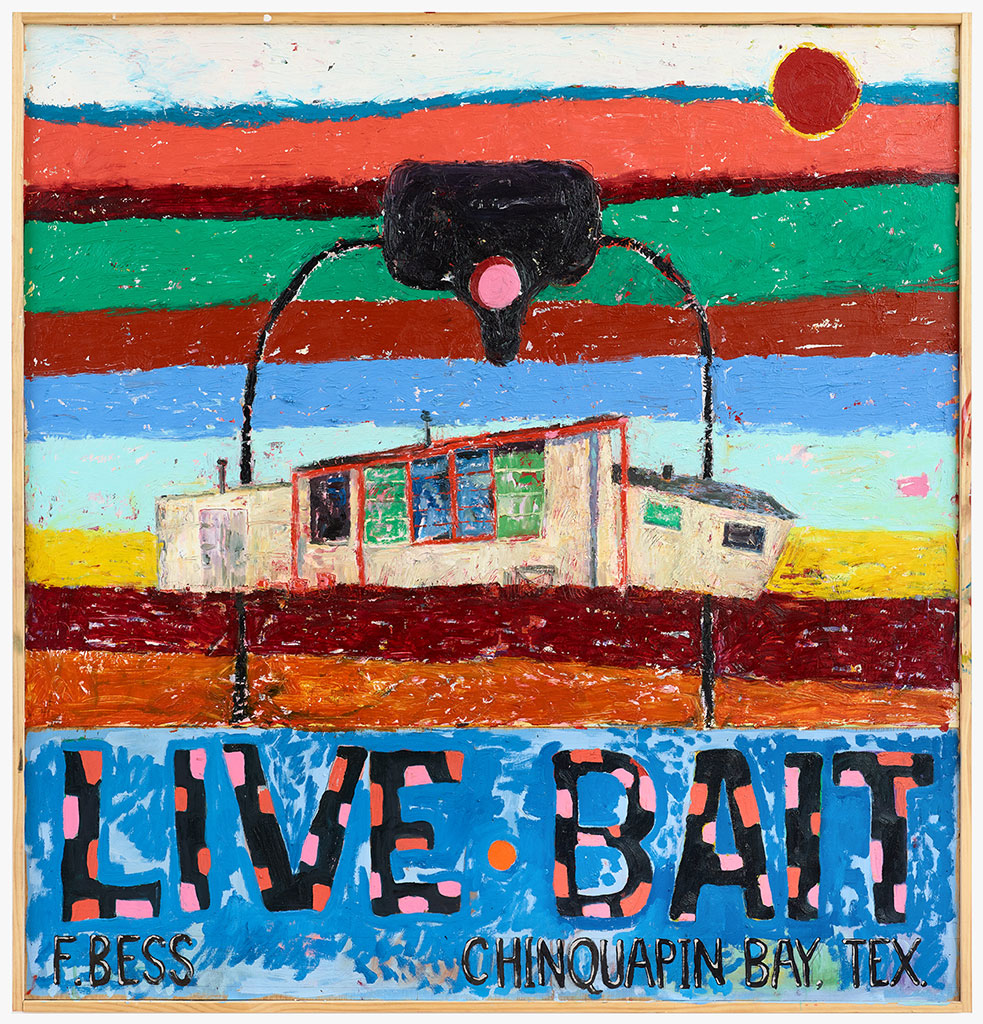

Forrest Bess, born on 5/10/1911 in Bay City, Texas where he also died on 11/111977, is considered an outstanding yet rather enigmatic figure in American postwar art. For most of his adult years lived on a fishing camp in nearby Chinquapin Bay on the Gulf of Mexico. Frequently relegated to the peripheries of art history, both as a Texas native and a rarely understood queer man, Bess might nevertheless be re-located at the heart of American Modernism.

Forrest Bess, born on 5/10/1911 in Bay City, Texas where he also died on 11/111977, is considered an outstanding yet rather enigmatic figure in American postwar art. For most of his adult years lived on a fishing camp in nearby Chinquapin Bay on the Gulf of Mexico. Frequently relegated to the peripheries of art history, both as a Texas native and a rarely understood queer man, Bess might nevertheless be re-located at the heart of American Modernism.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Fridericianum Archive

By featuring 70 works from Institutional and Private Collections the exhibition “Forrest Bess”, at the Fridericianum in Kassel, maps the artist’s development from his early conventional, figurative formulations through to his so-called “visionary” paintings (the biomorphic abstractions) that make up the main body of his work. Furthermore, by exhibiting selected correspondence and other archival material, Bess’s biography is carefully traced while at the same time providing a background to his art theoretical approaches, the handling of his homosexuality, and his theories of hermaphroditism. This insight into the life and work of an artist who has found a considerable following among contemporary artists, such as Tomma Abts, James Benning, Robert Gober, Richard Hawkins, Henrik Olesen, and Amy Sillman, strongly highlights Bess’s relevance to the present day.

Forrest Bess was born in Bay City, Texas, a small town 130 kilometers southwest of Houston, he grew up among the oil fields of East Texas where his father worked as a manual laborer. He took a few art lessons from a neighbor as a child, but largely taught himself to draw and paint by copying illustrations from books and magazines. After high school, Bess hoped to pursue his interest in art; however, his conservative parents regarded it as an impractical pursuit. He compromised, enrolling in university as an architecture student, first at Texas A&M University and later at the University of Texas. Although he failed to earn a degree at either school, both provided Bess with access to diverse libraries in which he immersed himself, developing interests in a variety of fields, including literature, mythology, philosophy, and psychology. One book in particular, Havelock Ellis’s “Psychology of Sex”, helped Bess come to terms with his homosexuality on some level. Throughout his life, however, he remained alienated from both the gay and straight communities, feeling that he was too masculine for the former and too effeminate for the latter. When the United States entered World War II, Bess enlisted in the military, where due to his interest in drawing and painting he was assigned to design camouflage patterns. One evening Bess revealed his homosexuality and was beaten by a fellow enlistee, resulting in a serious head injury. Bess subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown and was treated by an army psychiatrist who encouraged him to paint the visions he had experienced since childhood as a form of therapy, a practice he continued for more than twenty years. Despite living an isolated existence, Bess’s paintings captured the attention of a number of his contemporaries, and several solo exhibitions of his work were held at the prominent Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City.

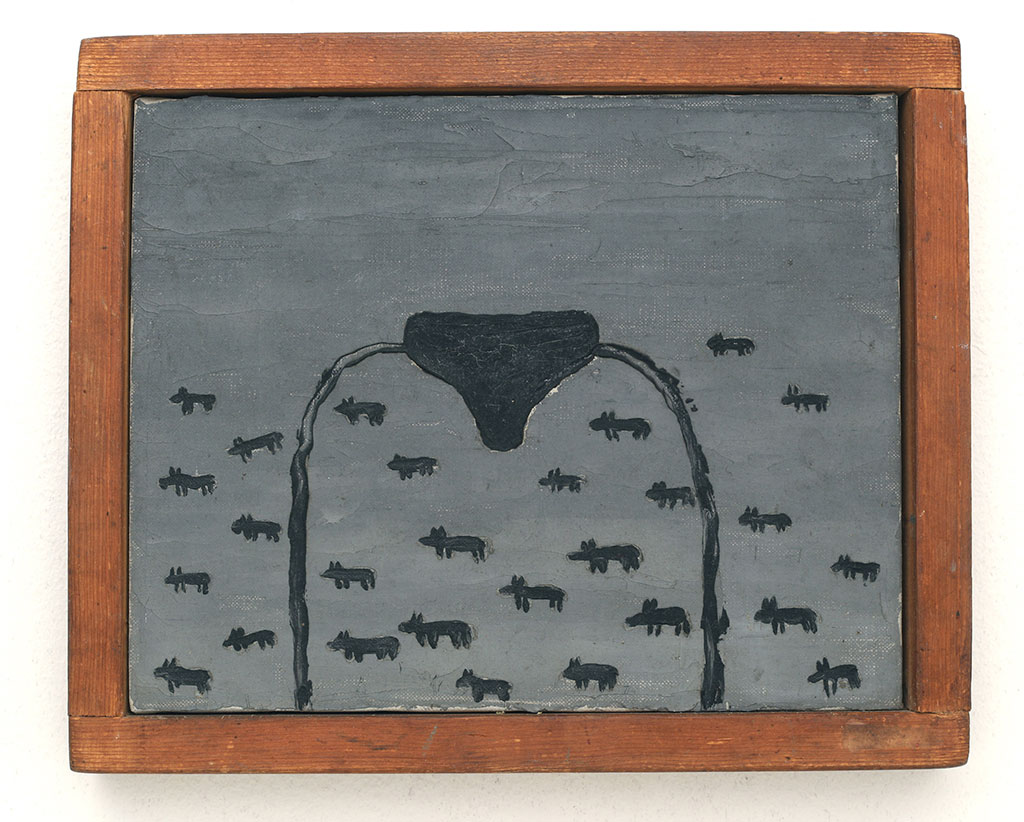

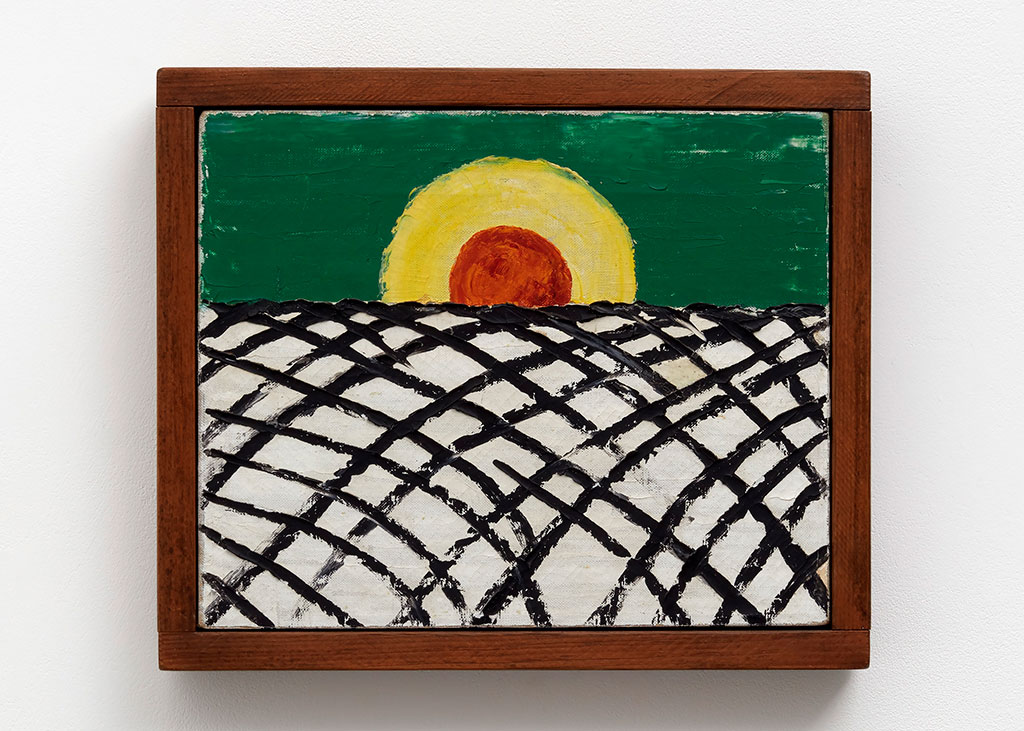

Although Bess painted figurative canvases from time to time throughout his life, he is best known for the powerful small-scale visionary paintings that he began to produce in earnest after his discharge from the Army. Feeling he could only fully explore his visions in solitude, Bess moved to live full-time at a fishing camp accessible only by boat, earning a meager living fishing for and selling bait. Bess found that the biomorphic shapes and abstracted landscapes of his visions usually occurred as he moved between consciousness and unconsciousness, just before falling asleep, or immediately upon waking. He kept a notebook by his bedside in which he sketched his visions as they occurred. With a simple black-and-white drawing Bess could access the vision again, even years later, to produce a painting. This method allowed him to record the compositions quickly, yet paint them very carefully. Bess developed an untutored but highly original and varied technique. He frequently used a palette knife to enliven his surface and mixed sand into his paint to create texture. He often juxtaposed areas of matte and shiny paint, as well as passages applied thickly and thinly. Using primarily unmixed paint, Bess employed striking combinations that he rarely repeated. No rules reliably govern his compositions. He sometimes places masses of small shapes into areas of pattern, and just as often arranges a single or pair of elements into a central, iconic formation. Bess crafted simple handmade frames out of salvaged wood, which reinforce the unselfconscious and utterly unpretentious appearance of his canvases.

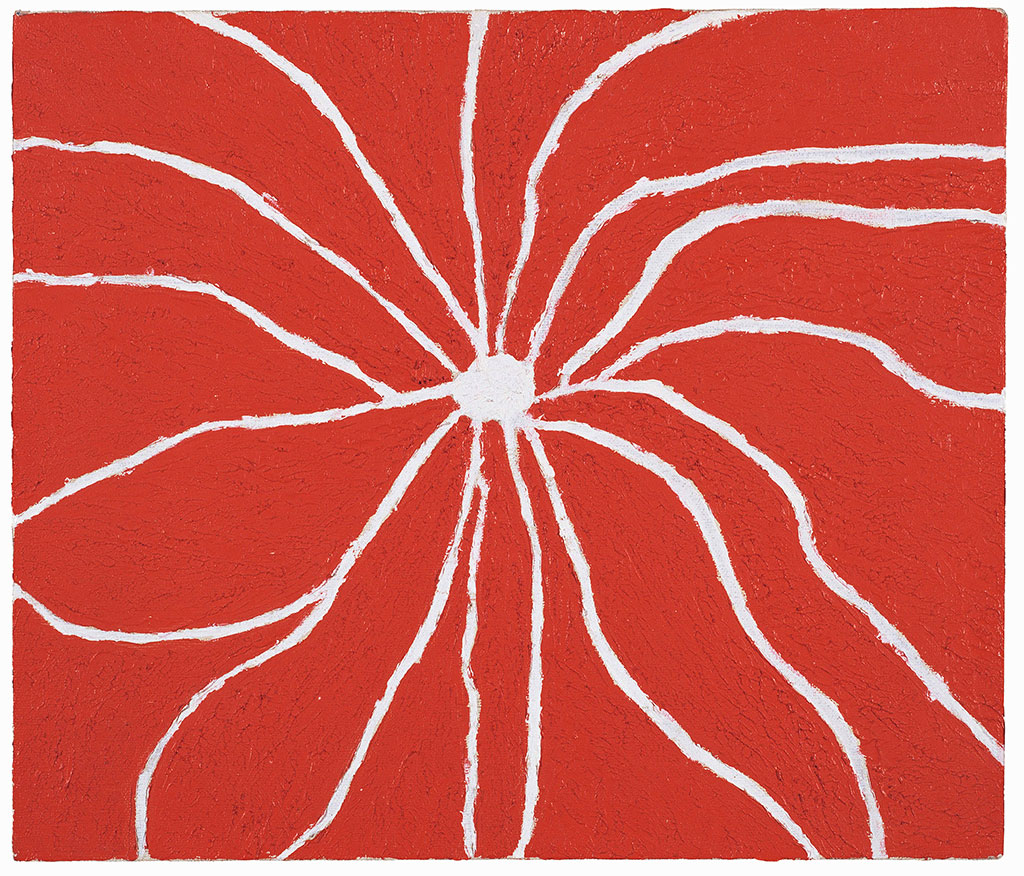

The sturdy wooden frames served a practical purpose for Bess, for his paintings were meant to be held and studied. After reading the work of the psychologist C. G. Jung, Bess came to believe that the symbols that appeared in his visions derived from what Jung, the Swiss founder of analytical psychology, called the “collective unconscious” a theoretical source of imagery and knowledge shared by all humankind. Bess hoped that these abstract, mythic images would reveal ancient and universal truths. The study of his paintings combined with his readings in alchemy, mythology, and anthropology led him to the belief that the key to everlasting health lay in transforming the body to become a hermaphrodite. Bess was so convinced of his conclusion that he assembled a lengthy, illustrated thesis (now lost) of his ideas. He presented this text to a number of researchers so that he could share what he had discovered in order to better society. To test his thesis Bess altered his own body in an attempt to become what he called a “pseudohermaphrodite”: He made a cut in the underside of his penis that he hoped to dilate enough to approximate a vagina, thus uniting the male and female within himself. Bess believed that having intercourse in this pseudohermaphroditic state would be regenerative, restoring youth and vigor to his body, and ultimately bestowing immortality. Though he obtained further surgery, Bess never achieved a satisfactory result and felt that his experiment was never fully realized. Bess began assembling charts of the meanings he “discovered” in his imagery in the early 1960s, in some cases many years after the paintings were made. These charts, several versions of which may be found among the voluminous correspondence by Bess preserved in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, reveal a radically simplified version of Bess’s complicated thesis. According to his schema, red represents male, white female, a triangle stands for the act of cutting, a circle denotes a hole, and a square the act of stretching. Some paintings can be read using these clues, such as “Untitled (The Spider)” from 1970, where red (male) and white (female) together create a hermaphroditic form. A white circle (hole) in the center of a square (to stretch) canvas can be interpreted as the stretching of a hole, corresponding to the attempted modification of Bess’s body. Bess occasionally hints at the theories underpinning his work through his titles: “Sign of the Hermaphrodite” (1953) or “The Penetrator” (1967). Most of his canvases, however, are untitled or have titles that may suggest a symbolic reading or mythic source without directly revealing their meaning. Even with the hints provided, Bess’s small, sometimes crude, abstract canvases resist an easy resolution, their apparent matter-offactness hiding a complex imagination. In 1961 a hurricane destroyed Bess’s home and studio along with an unknown number of paintings. Although he tried to rebuild, he was forced to move back to Bay City. He continued to paint until around 1970, but his mental and physical health declined. Bess entered a nursing home in 1974 and died in 1977, ten years after his last exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery and largely forgotten outside of Texas. Although Bess never achieved his dream of immortality, his paintings remain fully alive.

Info: Fridericianum, Friedrichsplatz 18, Kassel, Duration 15/2-3/5/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00, https://fridericianum.org