PHOTO:The Supermarket of Images

We live in a world that is increasingly saturated with images. Their number is growing so exponentially that the space of visibility seems to be literally inundated. As if it can no longer contain the images that constitute it. As if there were no more room, no more interstices between the images. The works and artists chosen for the exhibition “The Supermarket of Images” cast a keen and watchful eye over these issues. On the one hand, they reflect the upheavals that currently affect the economy in general, whether in terms of unprecedentedly large storage spaces, the scarcity of raw materials, labour and its mutations into intangible forms, or in terms of value and its new manifestations, such as cryptocurrencies. On the other hand, however, these works also question what happens to visibility in the age of globalized iconomies.

We live in a world that is increasingly saturated with images. Their number is growing so exponentially that the space of visibility seems to be literally inundated. As if it can no longer contain the images that constitute it. As if there were no more room, no more interstices between the images. The works and artists chosen for the exhibition “The Supermarket of Images” cast a keen and watchful eye over these issues. On the one hand, they reflect the upheavals that currently affect the economy in general, whether in terms of unprecedentedly large storage spaces, the scarcity of raw materials, labour and its mutations into intangible forms, or in terms of value and its new manifestations, such as cryptocurrencies. On the other hand, however, these works also question what happens to visibility in the age of globalized iconomies.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Jeu de Paume Archive

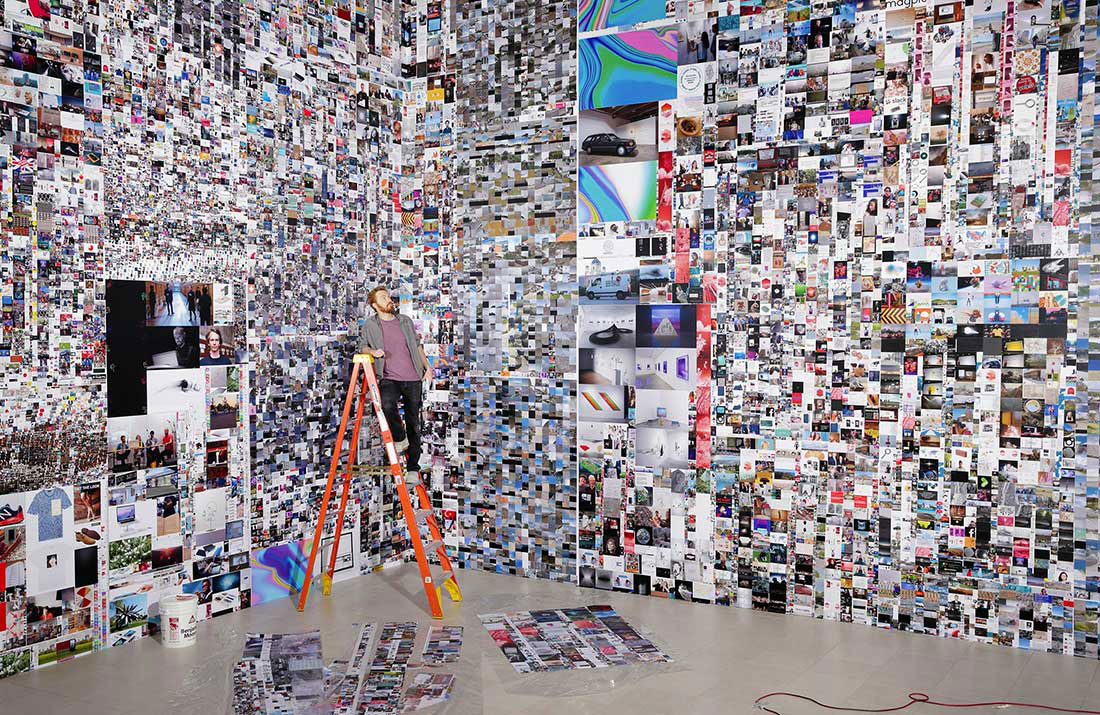

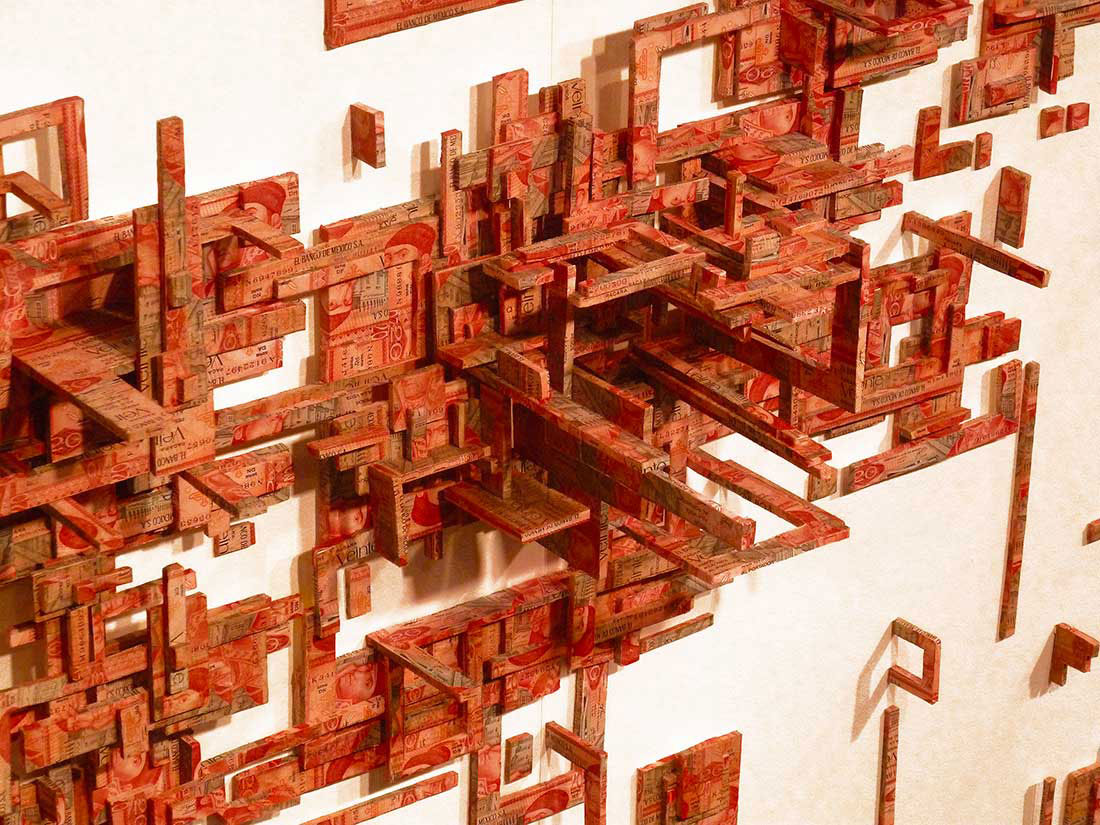

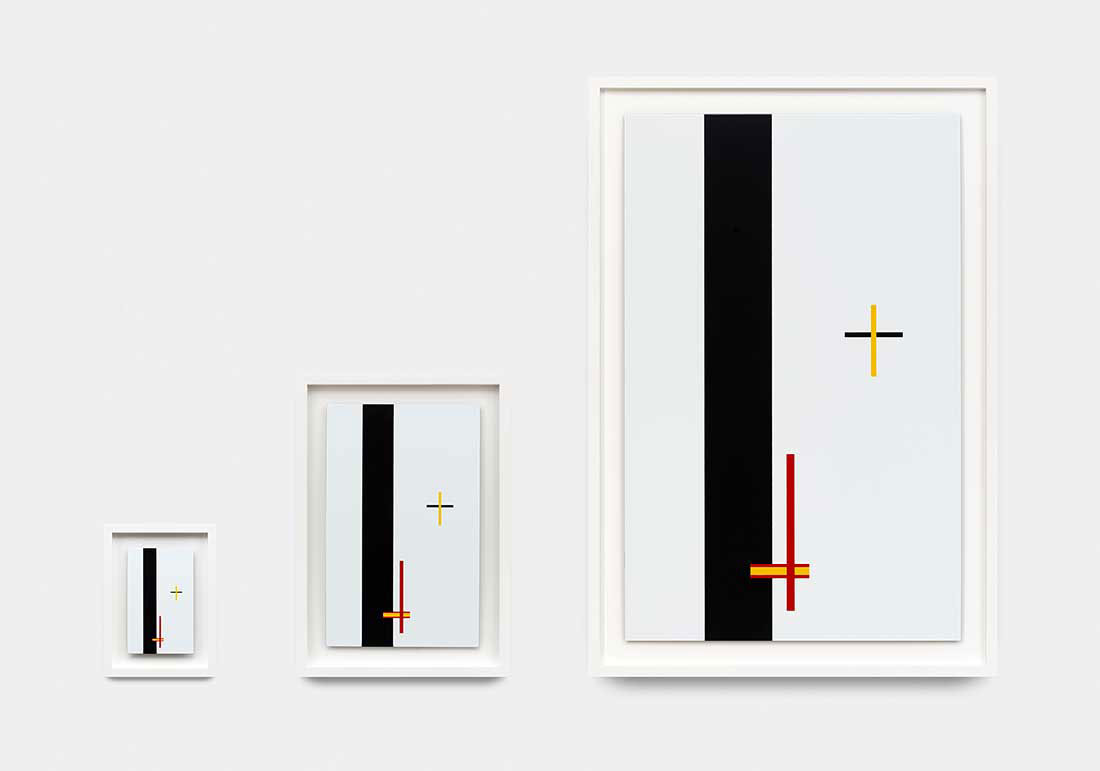

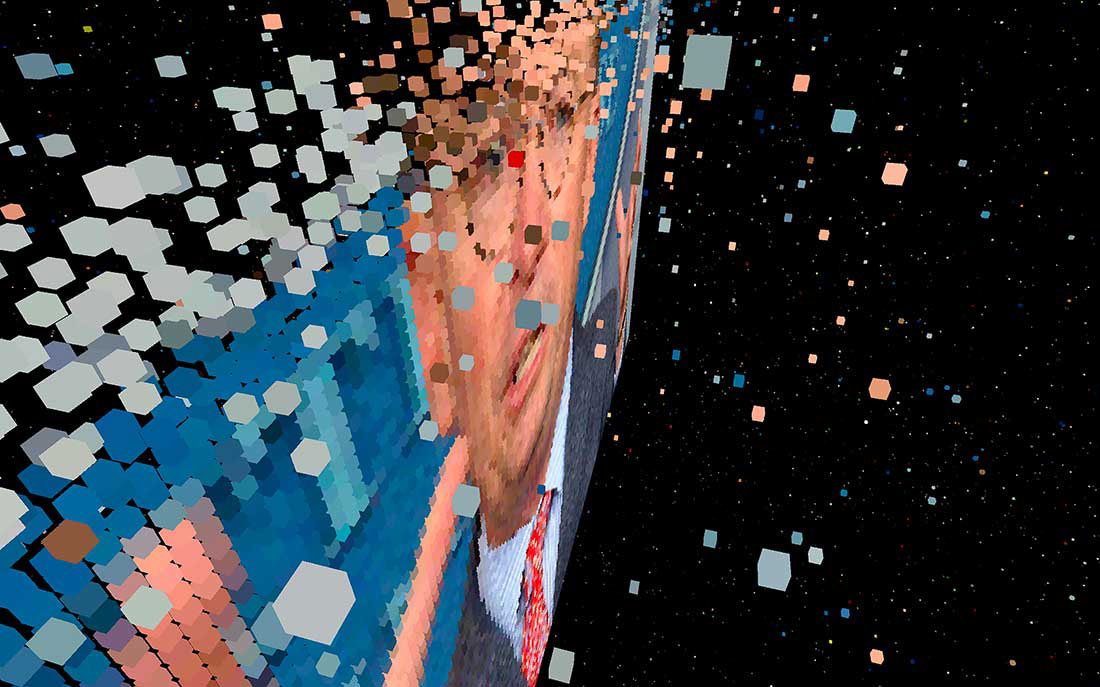

With his monumental photograph “Amazon” (2016) Andreas Gursky delivers a memorable image of the vast warehouses of today’s commodified culture. But images themselves are also stockpiled – to the point of overflowing, as in the cascade of 22,000 negatives Ana Vitória Mussi stages in “Por Um Fio” (1977–2004) or the avalanche of internet pages accumulated in the cache memory that Evan Roth has used to cover museum spaces in “Since You Were Born” (2019-20). For “Storage” (2019), Geraldine Juárez has cast old or recent media supports, such as cassettes or USB sticks, in ice. But by placing the gettyimages® watermark on a mirror in “Gerry Images” (2014), she suggests that the entirety of the visible could turn into a data bank. The beginnings of this becoming-stock of visibility can be seen in the collection of photography manuals from various periods that Zoe Leonard has piled up in “How to Make Good Pictures” (2016) and perhaps already in the diagrams that Kazimir Malevich used to represent the great movements of iconic circulation in the history of art. The delicacy of the wax that forms Elena Modorati’s transparencies in “On Balance (dare e avere)” (2019) contrasts with the thick slime of crude oil in the works “YES” (2007) by Andrei Molodkin and “Silver Shell” (2015) and “Horizon II” (2016) by Minerva Cuevas. There seems to be an infinite variety of materials that make up the visible: Chia Chuyia has woven a protective screen from leek strands in “Knitting the Future” (2015-20) and Thomas Ruff dissolved mangas that he found on the internet into colored flows as in “Substrat 8 II” (2002). But the raw material of the image today is above all its grain, its resolution, as can be seen in the pixels that coalesce and separate in Jeff Guess’s “Addressability” (2011) or the screenshots of a scrambled WhatsApp conversation in Taysir Batniji’s “Disruptions” (2015-17). Ultimately, today’s production of the visible is essentially based on code: in “Visible Hand” (2016), an allusion to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”, Samuel Bianchini index-links the image texture – the numbers and letters that compose a low-definition hand icon – to the real-time movement of stock indices. In the collective project “Eine Einstellung zur Arbeit”, they launched in 2011, Harun Farocki and Antje Ehmann gather two-minute film sequences in order to create an encyclopedia of the different forms of work in the world. Others are interested in idleness: Emma Charles, for example, filmed the stock exchange after the close of trading in “After the Bell” (2009). Among the many images of work or its underside, there are some that depict the making of the images themselves, a process that has changed considerably. While László Moholy-Nagy’s “Telephone Pictures” (1923) are probably the first pictures assembled entirely by sending remote instructions, image teleworking today is all about mass-produced “hashtags” and “likes” by digital workers, the theme of Martin Le Chevallier’s “Clickworkers” (2017). Ben Thorp Brown documents the manufacture of “deal toys” – trophies commemorating financial transactions “ “Toymakers” (2014). The mere fact of looking can sometimes be work in disguise: as Aram Bartholl points out with his gigantic Captchas from the series “Are You Human?” (2017), those image puzzles that Google asks you to recognize in a search are not only used to distinguish humans from robots, but also to improve recognition or automatic driving software. Money has been a recurring visual motif, from Hans Richter’s 1928 short film on inflation to the large-scale wall installations that Máximo González composes from obsolete banknotes in “Degradación” (2010). Value permeates into everyday gestures: Robert Bresson has choreographed hands grabbing banknotes in “L’Argent” (1983), and Sophie Calle has collected video surveillance images from a cash dispenser to show us the gaze of people looking at money in the works “Cash Machine” (1991-2003) and “Unfinished” (2003). Materiality is a crucial issue for art and finance in the age of cryptocurrencies: Yves Klein exchanged “zones of immaterial pictorial sensibility” (in the form of a cheque) for gold, while Kevin Abosch uses his own blood to print the address of the blockchain that represents the ten million virtual works of the “IAMA COIN” series (2018). Art itself may be an object of speculation (Kunst=Kapital, Joseph Beuys famously wrote on banknotes), but it also makes it possible to visualize the most elusive of speculative processes: Wilfredo Prieto multiplies the reflected image of a banknote between two mirrors in “One Million Dollars” (2002), while artists such as Femke Herregraven and the RYBN.ORG collective materialize or subvert the movements of stock-market algorithms. The movement of images has shifted from the leisurely page turning, in “Second-Hand Reading” (2013), William Kentridge evokes to the rapid unreeling featured in Richard Serra’s “Hand Catching Lead” (1968). Ultimately, the visible in its entirety has been mobilized. Images circulate through the high-speed cables photographed by Trevor Paglen, and their flow allows for the peer-to-peer exchanges tracked in the DISNOVATION.ORG collective’s “The Pirate Cinema” (2012). But viewers are also on the go: they ride on moving walkways (those of the 1900 Universal Exhibition), they take off in the lifts evoked by Pierre Weiss in “PATERNOSTER” (1995) and Maurizio Cattelan’s “Untitled” (2001).

On show are works by: Kevin Abosch, Aram Bartholl, Taysir Batniji, Samuel Bianchini, Robert Bresson, Sophie Calle, Maurizio Cattelan, Emma Charles, Chia Chuyia, Minerva Cuevas, Disnovation.org, Sergueï Eisenstein, Max de Esteban, Harun Farocki & Antje Ehmann, Sylvie Fleury, Beatrice Gibson, Máximo González, Jeff Guess, Andreas Gursky, Li Hao, Femke Herregraven, Lauren Huret, Geraldine Juárez, William Kentridge, Yves Klein, Martin Le Chevallier, Zoe Leonard, Auguste et Louis Lumière, Kazimir Malévitch, Elena Modorati, Lázló Moholy-Nagy, Andreï Molodkin, Ana Vitória Mussi, Trevor Paglen, Julien Prévieux, Wilfredo Prieto, Rosângela Rennó, Hans Richter, Martha Rosler, Evan Roth, Thomas Ruff, RYBN.ORG, Richard Serra, Hito Steyerl, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Ben Thorp Brown, Victor Vasarely and Pierre Weiss.

Info: Chief Curator: Peter Szendy, Associated Curators, Emmanuel Alloa and Marta Ponsa, Jeu de Paume, 1 place de la Concorde, Paris, Duration: 11/2-7/6/20, Days & Hours: Tue 11:00-21:00, Wed-Sun 11:00-19:00, www.jeudepaume.org

Right: Ana Vitoria Mussi, Por um fio, 1977-2004, © Ana Vitoria Mussi, Courtesy the artist and Gallery Lume, São Paulo

Right: Kevin Abosch, Personal Effect, 2018, © Studio Kevin Abosch, Courtesy Studio Kevin Abosch