ART CITIES:N.York-Sounds Lasting and Leaving

The exhibition “Sounds Lasting and Leaving” considers how the elusive medium of sound has carried through art since the early 1900s, when figures of Dadaism, Futurism, and Surrealism first began to experiment with audio. The exhibition juxtaposes aural and visual works by artists, many of whom are central to Luxembourg & Dayan’s program, while Duchamp was the subject of the gallery’s inaugural exhibition in 2009.

The exhibition “Sounds Lasting and Leaving” considers how the elusive medium of sound has carried through art since the early 1900s, when figures of Dadaism, Futurism, and Surrealism first began to experiment with audio. The exhibition juxtaposes aural and visual works by artists, many of whom are central to Luxembourg & Dayan’s program, while Duchamp was the subject of the gallery’s inaugural exhibition in 2009.

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Luxembourg & Dayan Gallery Archive

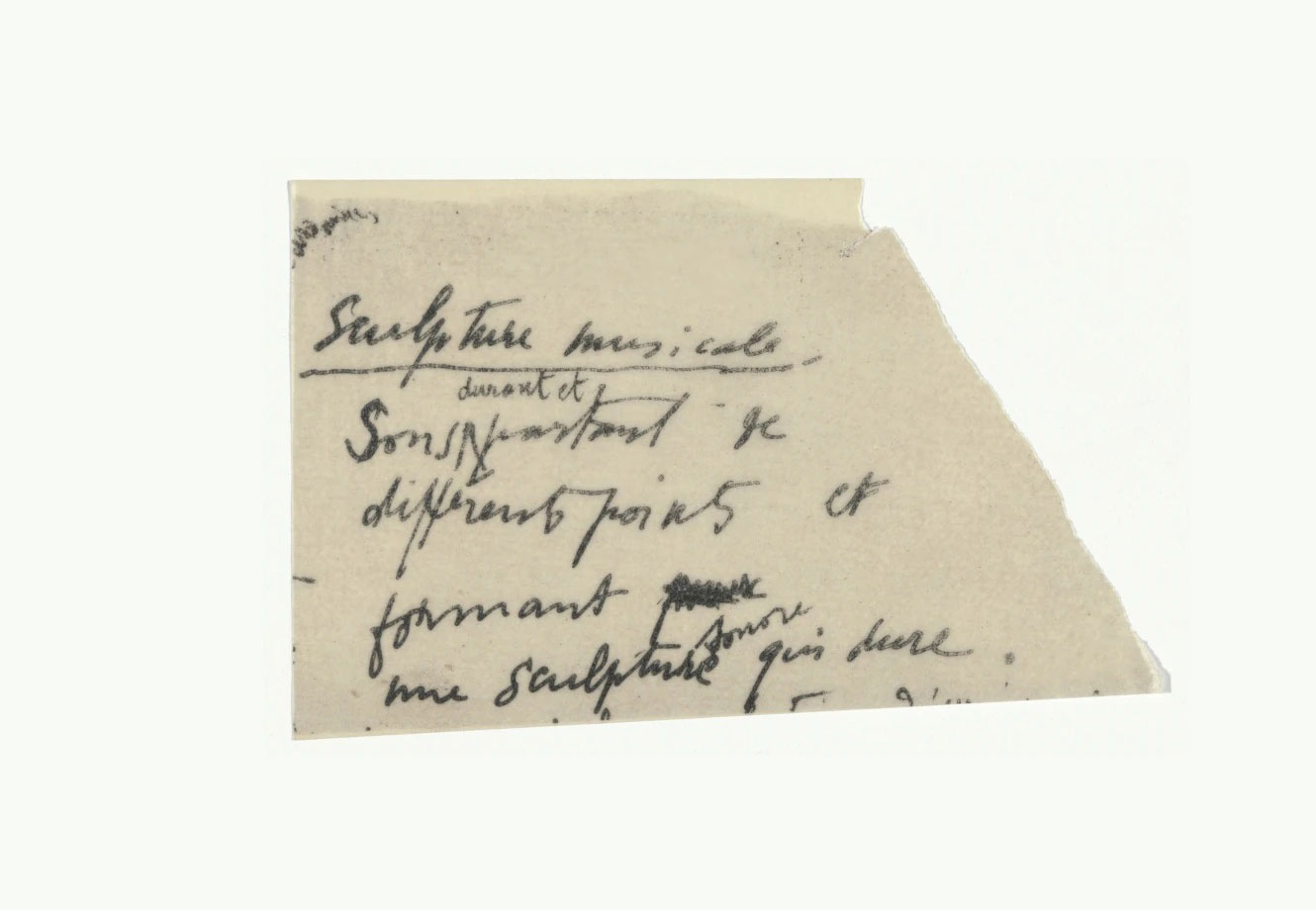

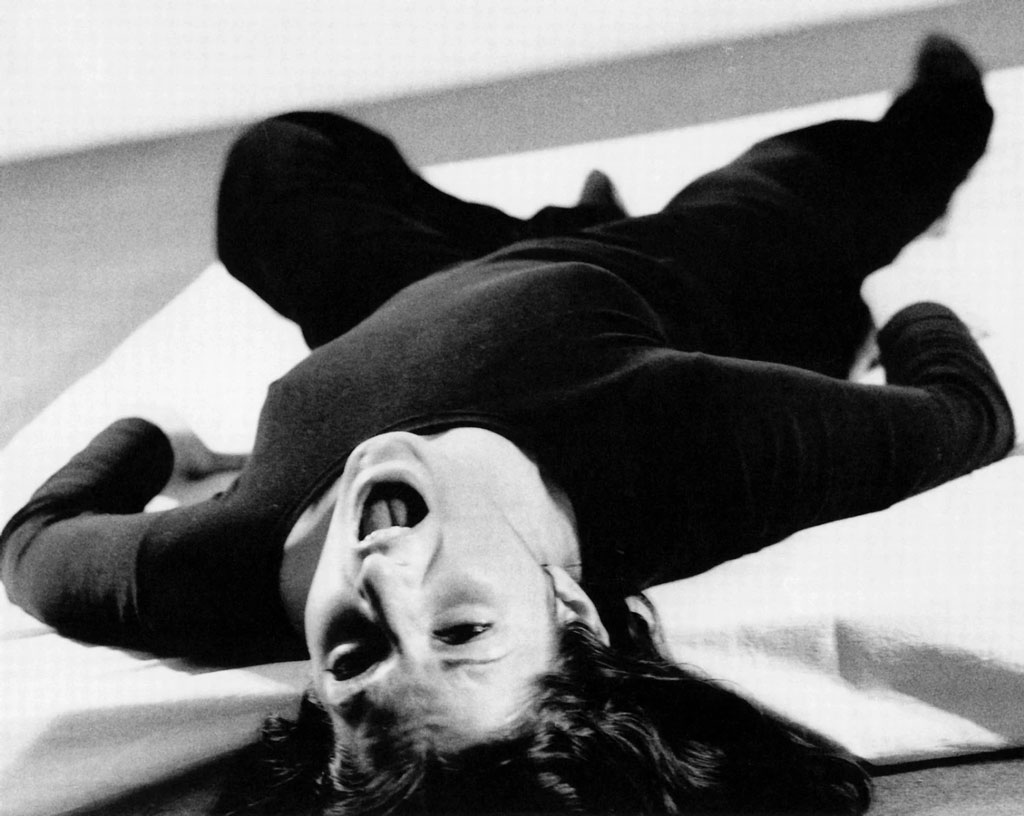

The exhibition’s title “Sounds Lasting and Leaving” , derives from a note that Marcel Duchamp jotted down circa 1912=21 and stored in “The Green Box” a collection of his records, photographs, and sketches. Translated from his native French, his text reads: “Musical Sculpture. Sounds lasting and leaving from different places and forming a sounding sculpture which lasts”. These slippery syllables indicate that Duchamp was grappling with the physical presence of sound while creating his first readymades, at a time when he made other noisy works that are included in the exhibition. Conceived around the turmoil and destruction of World War I, Marcel Duchamp’s “Musical Sculpture” expresses skepticism about sculptural permanence, proposing instead a medium that endures because of its immateriality. With his deceptively slapdash note, Duchamp captured the elusiveness of sound—its invisibility, its omnipresence, its shiftiness. Rather than avoid such ambiguity, scores of artists subsequently embraced audio because of that very quality. Duchamp’s sonic notions have influenced generations of artists. Before his death, the artist gave a copy of “Musical Sculpture” to John Cage, who in turn realized his own rendition by rewriting the original French note as a mesostic, which he then recited aloud and produced as a vinyl record in 1987. Cage’s delivery registers the conceptual underpinnings of the readymaster’s acoustic pursuits. Decades later, with her audio collages and found objects, Jennie C. Jones pays tribute to both Duchamp and Cage while probing unsung connections between modern art and avant-garde jazz. The exhibition explores such cross-generational riffs. Despite the art historical community’s waxing and waning attention to sound, the medium was fundamental to the advancement of modernism after Duchamp. It is not widely known that many of Alexander Calder’s early mobiles intentionally “gave off quite a clangor” (in his words), or that his titles often allude to noise or musical instruments. Calder’s piece included in the exhibition exemplifies his investment in sound. Importantly, the modern master befriended the avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse in the 1930s, and the two influenced one another’s practices. Many years later, this sonic dialogue between Calder and Varèse inspired Brooklyn-based Derrick Adams to develop a performance with composer Philippe Treuille. First mounted in 2013 at Salon 94 in collaboration with the Calder Foundation and Performa 13, this musical performance was restaged at the opening of exhibition and captured as an audio recording that will play throughout the exhibition’s run. With the rise of Fluxus, Conceptual art, and Body art in the 1960s and ’70s and revived interest in Duchamp during those postwar decades, artists once again turned to sound as a powerful means of dematerializing or recomposing the art object. As audio is perceived without vision or touch, these practitioners recognized its formal and conceptual potential. Joseph Beuys and Irma Blank were drawn to the performative capacity of noise and silence as a means of communication beyond language. The drawing practices of these German-born artists are infused with their own corporeal sounds, which counter the intelligibility of written and spoken words. In audio and video works, Vito Acconci and David Hammons used their own bodies as noise-making instruments to investigate New York City, depicting a sonic landscape that is at once raucous and romantic. Finally, Marina Abramović and Gino De Dominicis, who met in Italy in the 1970s, captured the intense guttural noises that humans emit when pushed to their physical limits, exploring how sound penetrates barriers of the body and space.

Info: Luxembourg & Dayan Gallery, 64 East 77 Street, New York, Duration: 22/1-14/3/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-17:00, www.luxembourgdayan.com