ART CITIES:N.York-Yun Hyong-keun

One of the most significant Korean artists of the twentieth century, Yun Hyong-keun is widely recognized for his signature abstract compositions, which engage with yet transcend Eastern and Western art movements and visual traditions. Using a restricted palette of ultramarine and umber, Yun created his compositions by adding layer upon layer of paint onto raw canvas or linen, often applying the next coat before the last one had dried.

One of the most significant Korean artists of the twentieth century, Yun Hyong-keun is widely recognized for his signature abstract compositions, which engage with yet transcend Eastern and Western art movements and visual traditions. Using a restricted palette of ultramarine and umber, Yun created his compositions by adding layer upon layer of paint onto raw canvas or linen, often applying the next coat before the last one had dried.

By Efi MIchalarou

Photo: David Zwirner Gallery Archive

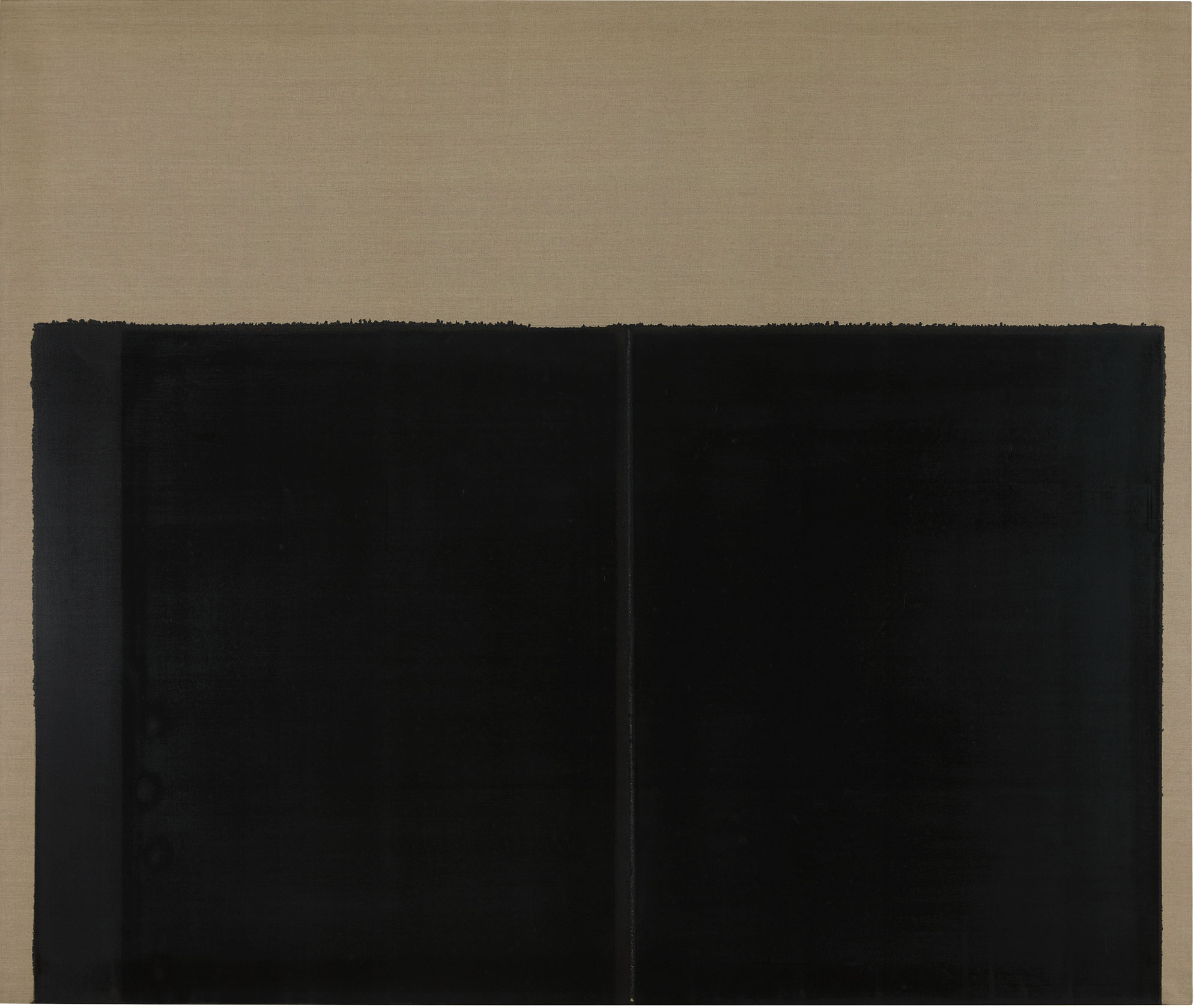

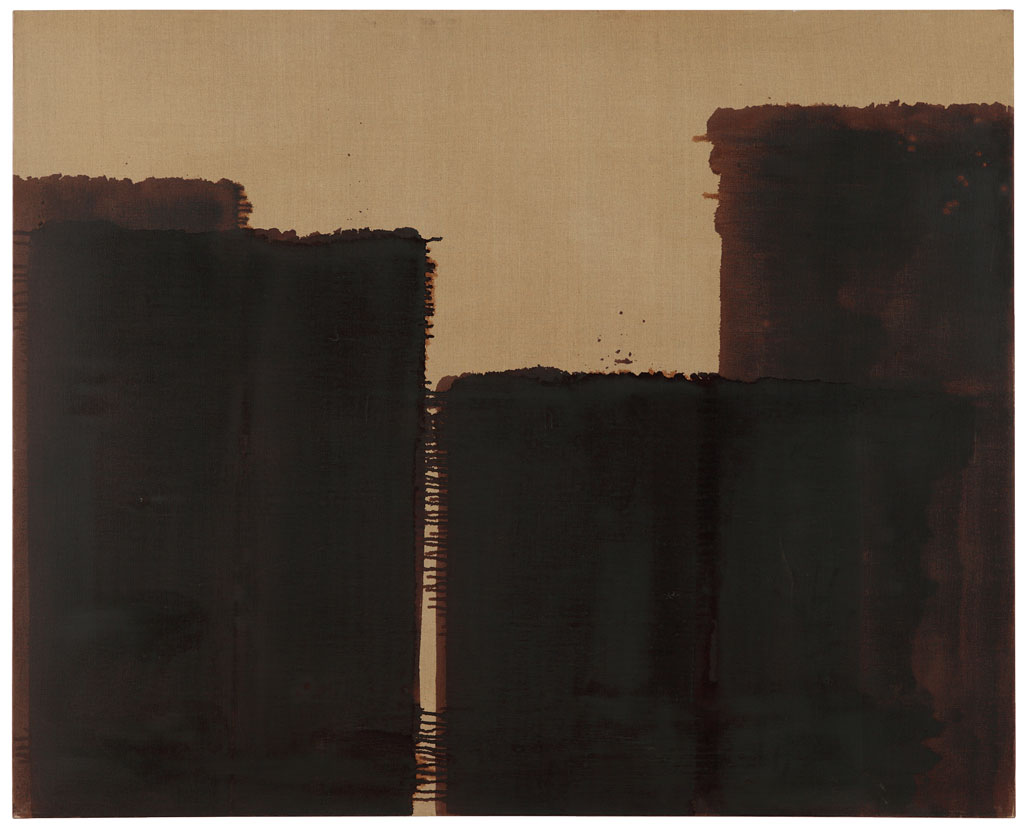

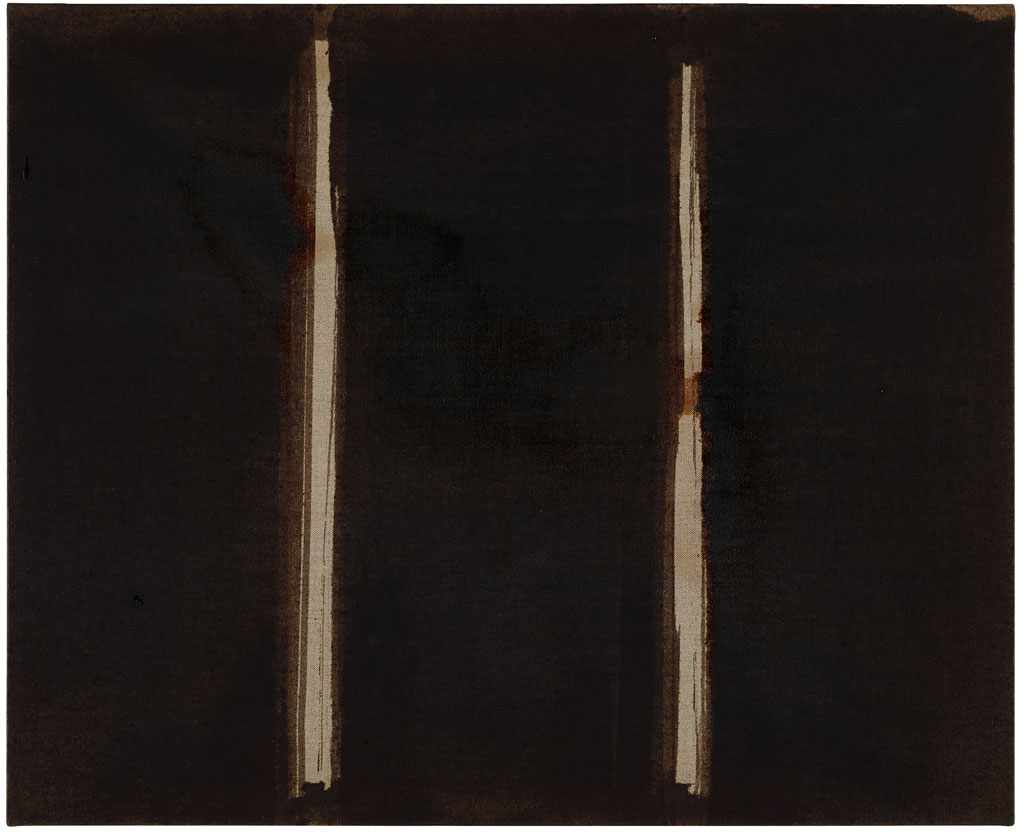

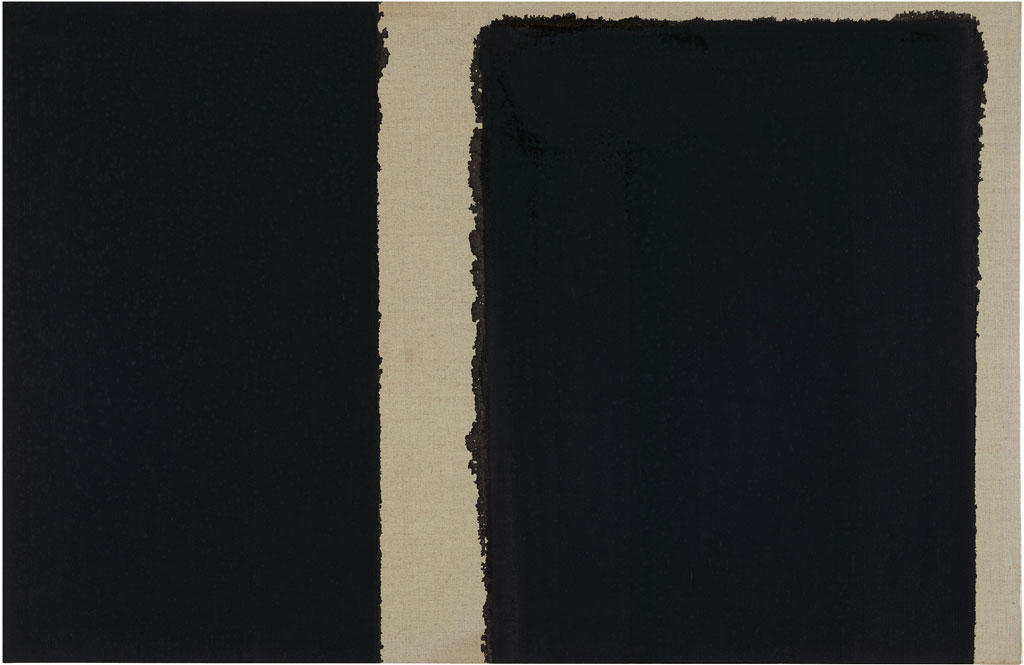

Yun Hyong-keun’s paintings in the exhibition at David Zwirner in New York, reflect a subtle evolution from his earlier canvases. The abstract forms in his works from the early 1990s become larger and darker. In the middle of the 1990s the lines in some of Yun’s paintings become tighter and straighter, and the edges of his forms appear less diffuse and more defined. While his art shows clear affinities to Minimalism, it also recalls the sublimity of Barnet Newman’s zip paintings, and the balance and diffuseness of Mark Rothko’s canvases. At the same time, Yun’s work exhibits the sophistication and restraint of traditional Korean scholarly painting, while also reflecting the artist’s unique sensitivity to color and material.

Born in 1928 in Cheongju, much of Yun Hyong-keun’s childhood was spent under Japanese occupation in Korea; he was 17 upon its termination in 1945. In 1947, he was set to study Western painting at Seoul National University (SNU), but was arrested and expelled that same year for taking part in the student protests against the school’s establishment by the U.S. Military Government in Korea. Protestors responded by suspending class, and Yun was among the 4,956 students to have their admission annulled (3,158 of them were, however, later allowed to return to the university). As the demonstration at SNU was a left-wing movement, Yun was suspected of being a communist in the following years. He was enlisted into the so-called Bodo League, an anti-communist organisation founded by the Korean government in 1949 to re-educate and convert those suspected of harbouring leftist tendencies. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the South Korean government arrested people on the Bodo League list, among them civilians who did not even know that they had been registered, or what the League was for—and many were executed. Yun was one of those who was rounded up and, as Kim Inhye explains, he narrowly escaped execution by hiding in a forest. Yun was then forced to work for the North Korean Army after becoming stranded in occupied Seoul, which led to six months of imprisonment in 1956 on charges of collaborating with communists, after the war ended. In the midst of state oppression, however, Yun was able to pursue his path as an artist. When he took the entrance exam for SNU, he met Kim Whanki, an influential modern Korean artist who was a professor at the university, and would become Yun’s lifelong mentor, friend, and father-in-law. By 1952, Kim had moved to teach at Hongik University in Seoul, and he allowed special admission for Yun so that he could continue studies there in 1954. Kim’s influences can be seen in Yun’s early paintings, many of which experiment with abstraction and feature bright colors. Both Yun and Kim are associated with the development of Dansaekhwa, a style of abstract painting that emerged in the 1970s in Korea. In a postwar environment struck by political instability and poverty, Yun and his contemporaries (among them Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, and Chung Sang-Hwa) turned to inexpensive and readily available materials as diverse as hanji or Korean paper, pencil, ink, coal, iron, and burlap sacks. Adopting equally diverse methods, Dansaekhwa artists focused on ways of manipulating material, including soaking, pulling, pushing, dragging, or ripping paper. Hoping to align past aesthetics with a contemporary visual language, Yun experimented with the absorbing ability of hanji, a Korean paper made from the bark of the mulberry tree, and adapted the results to cotton and linen as the unprimed surfaces on which he would paint using a method of mixing turpentine oil and pigment based on the traditional combination of water and ink. A common composition in Yun’s oeuvre consists of two black columns flanking either side of the canvas with the lighter shadow of the pigment pooling around the pillars. The blank space in between the black forms evokes a pathway into a new world or “the gate of heaven and earth”, as the artist described his painting practice, with blue representing the heaven and umber the earth. Yun’s early black-pillar paintings were time-consuming—during their making he would wait for the first layer of pigment to dry before applying multiple others. Over time, however, his works became increasingly simple, from the late 1980s, they feature black columns with more defined edges. In the early 1990s, Donald Judd travelled to Korea for a solo exhibition at Inkong Gallery in Seoul, where he encountered Yun’s paintings during a visit to his studio. Impressed by his work, Judd invited Yun to exhibit at the Donald Judd Foundation in New York 1993, and at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, in 1994. By this time, he was no longer seen as a communist threat, and in 1995, he represented Korea in the 46th Venice Biennale, thus cementing his significant contribution to Korean art.

Info: David Zwirner Gallery, 537 West 20th Street, 2nd Floor, New York, Duration: 17/1-7/3/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, www.davidzwirner.com

Right: Yun Hyong-keun, Burnt Umber & Ultramarine, 1993-1995, Oil on linen, 227.5 x 162 cm, Courtesy David Zwirner Gallery