ART-PRESENTATION: Marking Time-Process in Minimal Abstraction

During the 1960s and 1970s, many artists working with abstraction rid their styles of compositional, chromatic, and virtuosic flourishes. As some turned toward such minimal approaches, a singular emphasis on their interaction with materials emerged. The resulting pieces invite viewers to imaginatively reenact aspects of the creative process.

During the 1960s and 1970s, many artists working with abstraction rid their styles of compositional, chromatic, and virtuosic flourishes. As some turned toward such minimal approaches, a singular emphasis on their interaction with materials emerged. The resulting pieces invite viewers to imaginatively reenact aspects of the creative process.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archive

Featuring a selection of nearly 12 paintings and works on paper from the Guggenheim Collection by Agnes Martin, Roman Opałka, Park Seo-Bo, and others the exhibition “Marking Time: Process in Minimal Abstraction” explores how artists operating in a variety of contexts foregrounded process as they forged new approaches to abstraction. These works whether characterized by interlocking brushstrokes, a pencil moved through wet paint, or a pin repeatedly pushed through paper, invite viewers to imaginatively reenact aspects of the creative process. The artists who made this effect central to their art are associated with a variety of global movements. What unites them is not necessarily a shared belief in what art should accomplish or express, nor participation in a closely linked interpersonal network. Instead, it is their implicit trust in viewers’ capacity to put themselves in the artist’s position as they consider the object in front of them. It is a distinctively empathetic mode of engagement that relies on an awareness of oneself as inhabiting both a body and time, and, perhaps even more importantly, a consciousness of the embodied experiences of others.

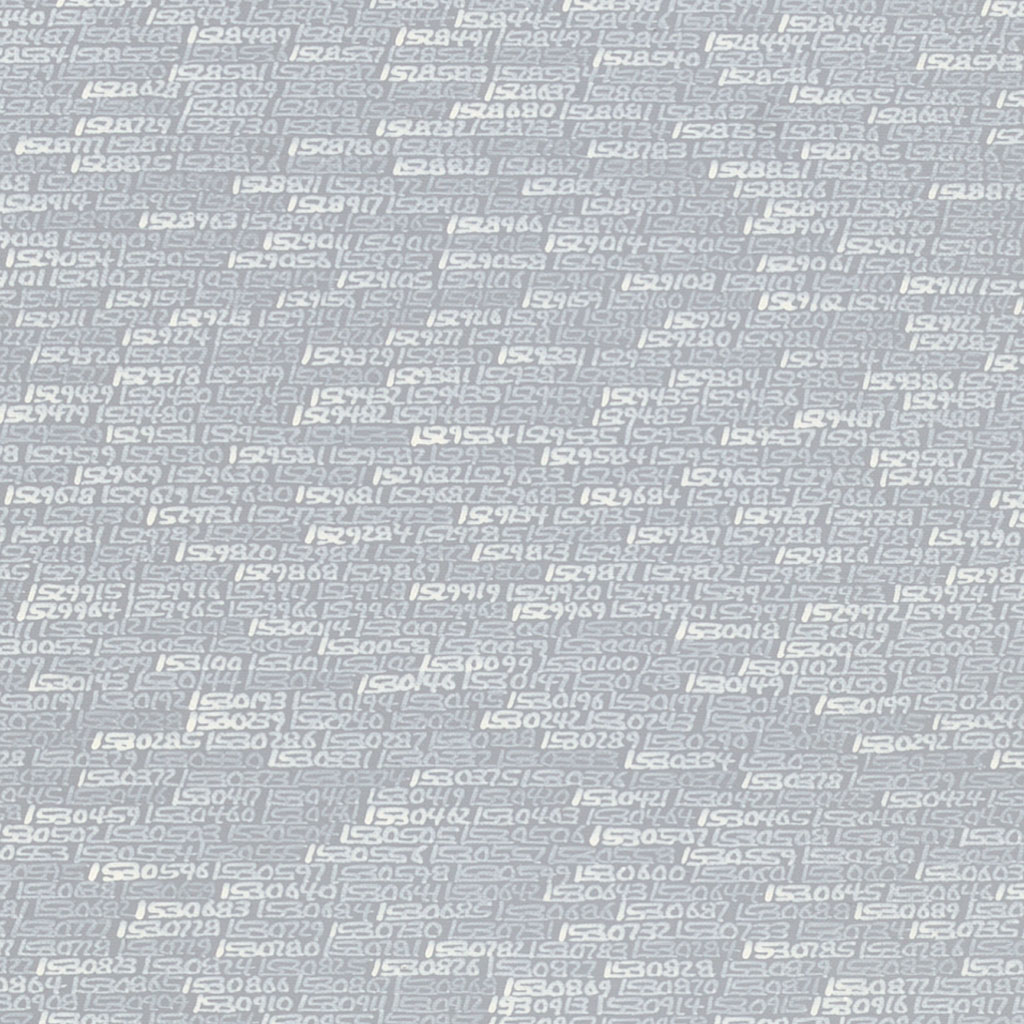

In 1965, while living in Warsaw, Roman Opałka embarked on his lifelong project “Opalka 1965/1 – ∞” (1956-2011). Each day he would obsessively paint numbers in increasing order, starting with 1, with white acrylic paint on identically shaped vertical canvases, all entitled “Détails”. He would end the canvas with a certain number, then start the next canvas with the subsequent number, and continue in that way. As the years passed, the canvases, initially black, became increasingly lighter: the last numbers, present but invisible, were painted white on white. With this ambitious project, Opalka gave tangible form to time and quantified the infinite, which by definition cannot be represented nor understood. From 1972, Opalka began working contemporaneously on a self portraiture project: the artist recorded himself saying the number he had just painted and he took a photograph of himself at the end of each day’s work. Opalka’s dedication to exploring the theme of the infinite came to an end in 2011 when he died.

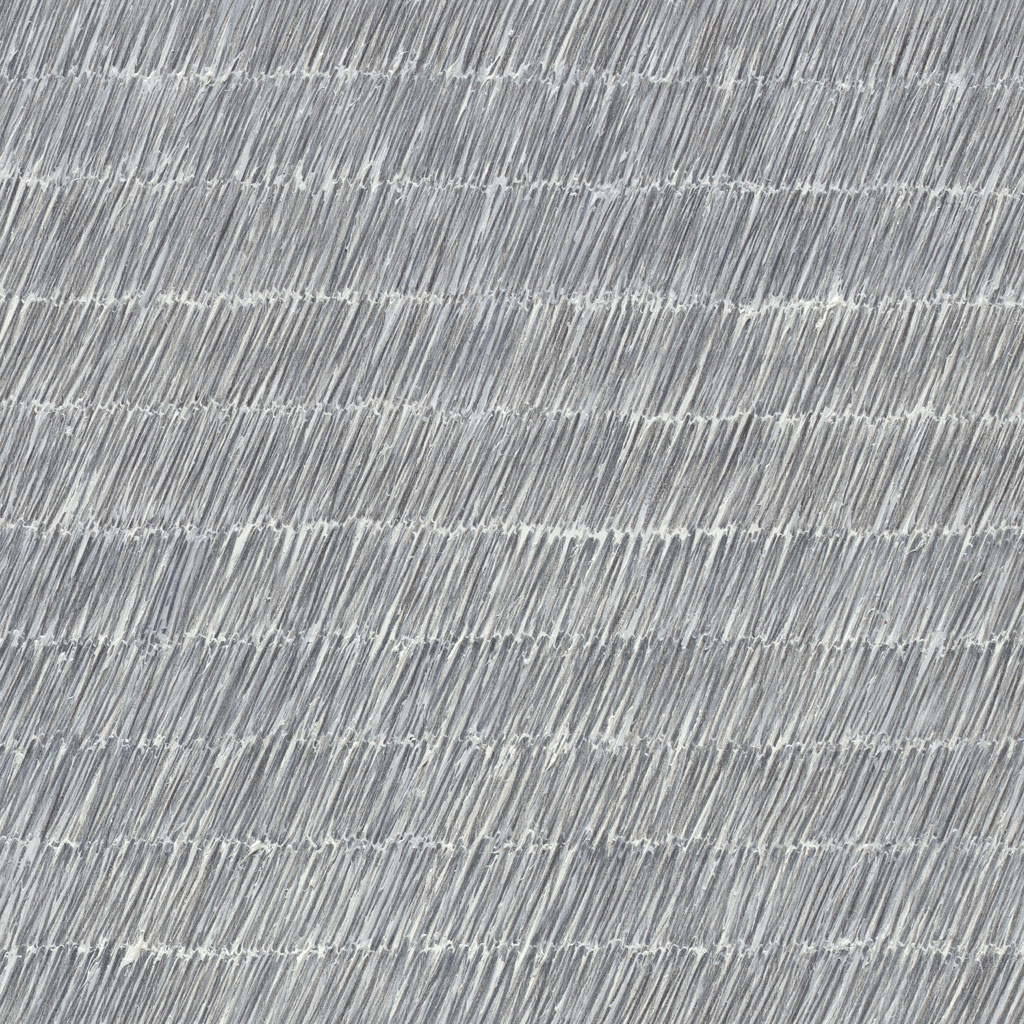

Park Seo-Bo is a seminal figure in Korean contemporary art and one of the founding members of the Dansaekhwa monochrome movement, a synthesis between traditional Korean spirit and Western abstraction, which emerged in the early 1970s in postwar Korea and has gained international recognition since. Although the Korean monochrome movement has never been defined with a manifesto, the artists affiliated with Dansaekhwa, including Chung Chang-Sup and Lee Ufan, are commonly known for their use of a neutral, their material emphasis on pictorial components and fabrics, and their gestural and systematic process. In Park Seo-Bo’s paintings, process and discipline prevail a departure from the artist’s early aesthetics, which were inspired by Art Informel, a French movement that arose parallel to American Abstract Expressionism during World War II and became prevalent in Europe throughout the 1950s. As early as 1957, he helped establish the Hyun-Dae Artists Association around the principles of Art Informel, the gestural and abstract techniques of which, like those of Action Painting and Color-field in the USA, would enable young Korean artists to express their anguish in the immediate aftermath of the Korean War.

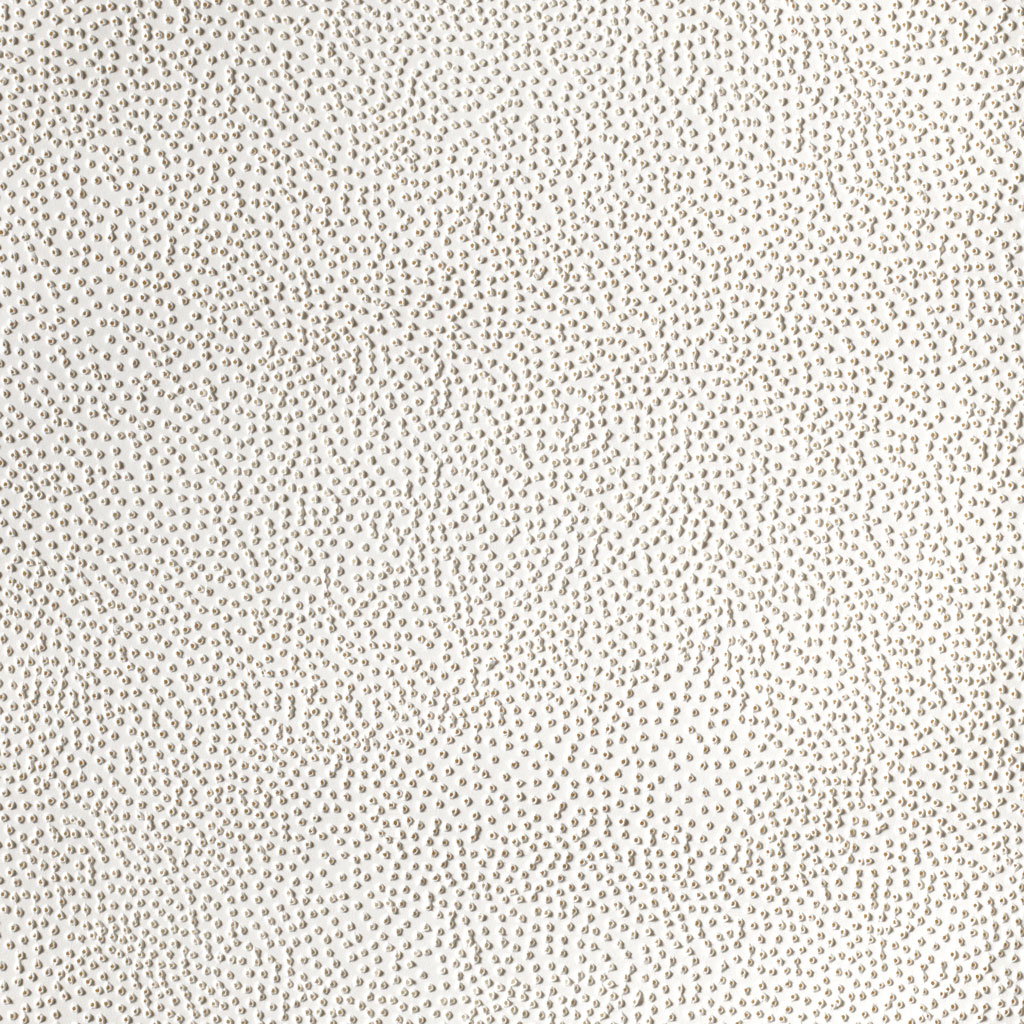

Born in 1937 in Aligarh, India, Zarina Hashmi, who prefers to use her first name only. After receiving a degree in mathematics, she went on to study woodblock printing in Bangkok and Tokyo, and intaglio with S. W. Hayter at Atelier-17 in Paris. The work of Zarina is defined by her adherence to the personal and the essential. An early interest in architecture and mathematics is reflected in her use of geometry and her emphasis on structural purity. While her work tends towards minimalism, its starkness is tempered by its texture and materiality. Her art poignantly chronicles her life and recurring themes include home, displacement, borders, journey and memory. Best known as a printmaker, Zarina prefers to carve instead of draw the line, to gouge the surface rather than build it up. She uses various mediums of printmaking including intaglio, woodblocks, lithography, and silkscreen, and she frequently creates series of several prints in order to reference a multiplicity of locales or concepts. For example, her seminal work “Home is a Foreign Place” consists of 36 woodblock prints, each of which represents a particular memory of home. Each subject is inscribed in Urdu beneath the print to signify the vital role language plays in her work, as well as to pay homage to a mother tongue in decline. Other works explore geographical borders and contested terrains, particularly those areas which are scarred from political conflict. She has long been interested in the material possibilities of paper and in addition to printing on it, she creates works which entail puncturing, scratching, weaving and sewing on paper. Zarina also creates sculpture using a variety of media such as bronze, aluminum, steel, wood, tin, and paper pulp.

Born on a farm in rural Saskatchewan, Canada, Agnes Martin immigrated to the United States in 1932 in the hopes of becoming a teacher. After earning a degree in art education, she moved to the desert plains of Taos, New Mexico, where she made abstract paintings with organic forms, which attracted the attention of renowned New York gallerist Betty Parsons, who convinced the artist to join her roster and move to New York in 1957. Over the course of the next decade, Martin developed her signature format: six by six foot painted canvases, covered from edge to edge with meticulously penciled grids and finished with a thin layer of gesso. Though she often showed with other New York abstractionists, Martin’s focused pursuit charted new terrain that lay outside of both the broad gestural vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism and the systematic repetitions of Minimalism. Rather, her practice was tethered to spirituality and drew from a mix of Zen Buddhist and American Transcendentalist ideas. In 1967, at the height of her career, Martin faced the loss of her home to new development, the sudden death of her friend Ad Reinhardt, and the growing strain of mental illness; she left New York, and returned to Taos, where she abandoned painting, instead pursuing writing and meditation in isolation. Her return to painting in 1974 was marked by a subtle shift in style: no longer defined by the delicate graphite grid, compositions display bolder geometric schemes, like distant relatives of her earliest works. In these late paintings, Martin evoked the warm palette of the arid desert landscape where she remained for the rest of her life.

Info: Curator: David Max Horowitz, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York, Duration: 18/12/19-20/7/20, Days & Hours: Mon, Wed-Fri & Sun 10:00-17:30, Tue & Sat 10:00-20:00, www.guggenheim.org