ARCHITECTURE:Gio Ponti-Loving Architecture, Part II

Gio Ponti was a highly influential Italian architect/designer and the creative force behind Domus magazine, which he founded and edited from 1928 to 1941 and again from 1948 to 1979). He was also a faculty member of the school of architecture at the Milan Polytechnic and practiced architecture and design professionally with Alberto Rosselli. While he broke new ground in the fields of design and furniture-making, Ponti is perhaps best known for the Pirelli Tower, a 33-story skyscraper in central Milan that was built with 33,000 cubic meters of pre-stressed, reinforced concrete (Part I).

Gio Ponti was a highly influential Italian architect/designer and the creative force behind Domus magazine, which he founded and edited from 1928 to 1941 and again from 1948 to 1979). He was also a faculty member of the school of architecture at the Milan Polytechnic and practiced architecture and design professionally with Alberto Rosselli. While he broke new ground in the fields of design and furniture-making, Ponti is perhaps best known for the Pirelli Tower, a 33-story skyscraper in central Milan that was built with 33,000 cubic meters of pre-stressed, reinforced concrete (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

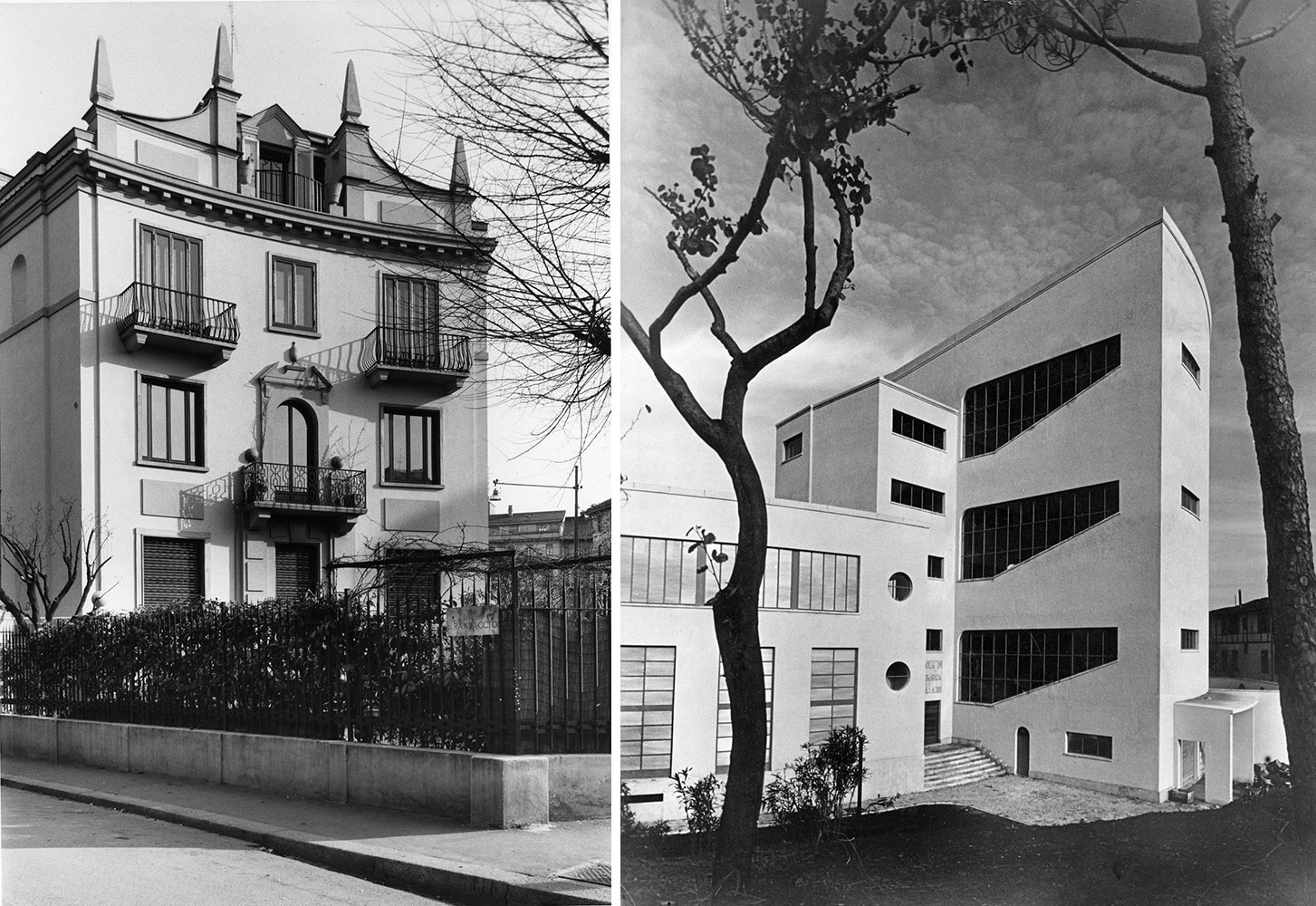

Photo: MAXXI Archive

Architect, designer, art director, writer, poet and critic, Gio Ponti was an allround artist who traversed much of the 20th Century, profoundly influencing the taste of his time, responding to its most significant demands and anticipating many of the themes of contemporary architecture. 40 years on from his passing, MAXXI, is devoting a major retrospective to this exceptional figure. The exhibition examines and presents his multi-faceted career, starting with an account of his architecture, a unique and original synthesis of tradition and modernity, history and progress, elite culture and quotidian existence. The exhibition title, “Loving architecture” echoes that of his best-known book, “Amate l’architettura”. On display are archive materials, original models, photographs, books, magazines and design classics closely associated with his architectural projects and organized into eight sections evoking key concepts expressed by Ponti himself. The sections are: Towards the exact house: The research of a definition of the exact house, or better the house that would be suitable to the life of those who dwell in it, the modern life of modern humans, was always central in Ponti’s production His research started from the typical Milanese Domus, i.e. from the origins of domestic tradition, developed through the pages of the magazines Ponti directed, “Domus” and “Stile”, and found its conclusion in Ponti’s apartment in Via Dezza – with its fluid spaces and visually connected rooms. A variety of types applicable to standardized lodgings can be found as early as the models designed for Feal, where adaptability was conjugated with the prefabrication of tower buildings. Living nature: Placed at the centre of Ponti’s design creativity, Nature establishes a biunivocal and osmotic relation with architecture. This is manifest when Ponti uses porticoes, terraces, pergolas and verandas, loggias and balconies as architectural elements that project architecture outside, and at the same time bring nature within. For Ponti, Nature par excellence reveals itself along the coasts of the Mediterranean, the cradle of classic architecture but also of modern architecture, as expressed by the projects studied with Bernard Rudofsky between the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1960s, the relationship between architecture and nature became more conceptual and took form in more organic and almost intimate projects, such as the house called Beetle under the leaf and the villa for Daniel Koo in California. Classicisms: The 1930s were a period which offered Ponti the opportunity to experiment with large projects, mostly on public procurement, characterised by a multi-scale vision, capable of integrating the urban dimension with the that of details. In the competition project for the Palazzo dell’Acqua e della Luce for the E42, in the university seats of Liviano and Palazzo del Bo in Padua, and in the School of Mathematics at Rome’s Città Universitaria, besides establishing a dialogue between architecture and art, Ponti started from the monumental scale and moved down to the design of interior spaces and furnishings. A similar method guided him in the design of the First Montecatini Building in Milan, undeniably a monument to labour, replicated and reiterated twenty years later with the Second Building. Architecture of the surface: Projects such as the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm or the Institute of Nuclear Physics at Sao Paulo in Brazil represent the accomplished expression of a design concept that reasons through planes rather than volumes. The façade becomes a two-dimensional surface that can be punctuated and folded as a sheet of paper. In the villas built in Caracas and Teheran, also thanks to the wealthy and enlightened clients, Ponti lightens the casing which detaches itself from the ground and reveals all his ability to handle complex plans, in which the domestic spaces follow one another and merge, with furnishing solutions and artistic interventions integrated into the architecture. These projects also attest to the international dimension that Ponti’s work had reached in the 1950s. Architecture as crystal: Ponti’s most telling and well known aphorism expresses the idea that the “finished form” is a guarantee of a correct architecture: It is not volume that makes architecture, but its closed, finished, immutable form. “Architecture […] when it is pure, is pure as a crystal, magic, closed, exclusive, autonomous, uncontaminated, incorrupt, absolute, definitive”. The faceted essence of the crystal manifests itself in the plan, with an elusive profile made of corners that multiply and chase each other without ever finding the absoluteness of two perpendicular faces, and in perforated and suspended surfaces that are the elevations of those plans. A consistent and univocal method that we find in impressive projects such as the Denver Art Museum or the chapel of San Carlo in Milan, and in the small scale design of door handles for Olivari, of bathroom fixtures for Ideal Standard, of ceramic tiles or the bodywork for a car called, not by chance, Diamante (Diamond). Light façades: The history of humanity, Ponti affirmed, advances from weight to lightness, from the big to the slender: the prophecy of “lightness” called for the rising of “a light and transparent style, a simple style connected to simplified social customs”. Therefore, lightness is not a literary metaphor for Ponti, but the answer to the construction methods of the 20th century, so much so that it takes on an ethical value, even before its formal one. The façades of buildings are “intact surfaces, as the white sheet of paper” on which the windows play the “arcane game of Architecture”, which is dematerialized as in the final result of the Co-cathedral of Taranto, where concrete becomes air and light. In his studies on prefabrication, his INA and Savoia office buildings in Milan, and his government buildings in Islamabad, the game of perforated façades wins over the lazy repetitiveness of elevations. Appearance of skyscrapers: Ponti’s aspiration towards lightness translated into and aspiration for verticality when applied to buildings that were to be inserted in a consolidated urban context. A vertical development in fact allows a limited footprint and allowed Ponti to foretell the appearance of skyscrapers in the skyline of modern cities. In his design of high-rise buildings, the plan remains however a finite form, closed and absolutely original. In his study of triangular-plan skyscrapers, the plan is functional to a multiplication of continuous window views, and a similar choice of light façades permeates the design for the Montreal Towers and that for the Italo-Brazilian Centre in Sao Paulo. However, Ponti’s skyscraper par excellence is the Pirelli Tower in Milan, a synthesis of many design themes presented in this exhibition. The spectacle of cities: On an urban planning level, Ponti developed an idea of the city that is intimately linked to the vertical development of architecture. He demonstrated this already in 1937 with the regeneration project of the former Scalo Sempione, where he fought against the concept of a horizontal garden district in favour of an organic composition of large ensembles placed along a wide tree-lined avenue, which ten years later (when he worked on the project once more with Mazzocchi and Minoletti) became the “Green River”, a backbone with sports facilities and tall collective buildings. Even on the small scale of a mountain town, Chiavenna, his proposal for a “School City” reflects the organic vision of an education district integrated into the fabric of the historical centre.

Info: Curators: Maristella Casciato, Fulvio Irace, Margherita Guccione, Salvatore Licitra and Francesca Zanella, MAXXI- Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Via Guido Reni 4A, Rome, Duration: 27/11/19-13/4/20, Days & Hours: Tue & Fri-Sat 11:00-20:00, Wed-Thu & Sun 11:00-19:00, www.maxxi.art