TRACES: Lee Krasner

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most critical figures in the evolution of American art in the second half of the 20th Century, Lee Krasner (27/10/1908-19/6/1984). Lee Krasner was the only woman among originators of Abstract Expressionism, she nevertheless found relatively little recognition until some years after the death of her husband, Jackson Pollock, in 1956. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind one of the most critical figures in the evolution of American art in the second half of the 20th Century, Lee Krasner (27/10/1908-19/6/1984). Lee Krasner was the only woman among originators of Abstract Expressionism, she nevertheless found relatively little recognition until some years after the death of her husband, Jackson Pollock, in 1956. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

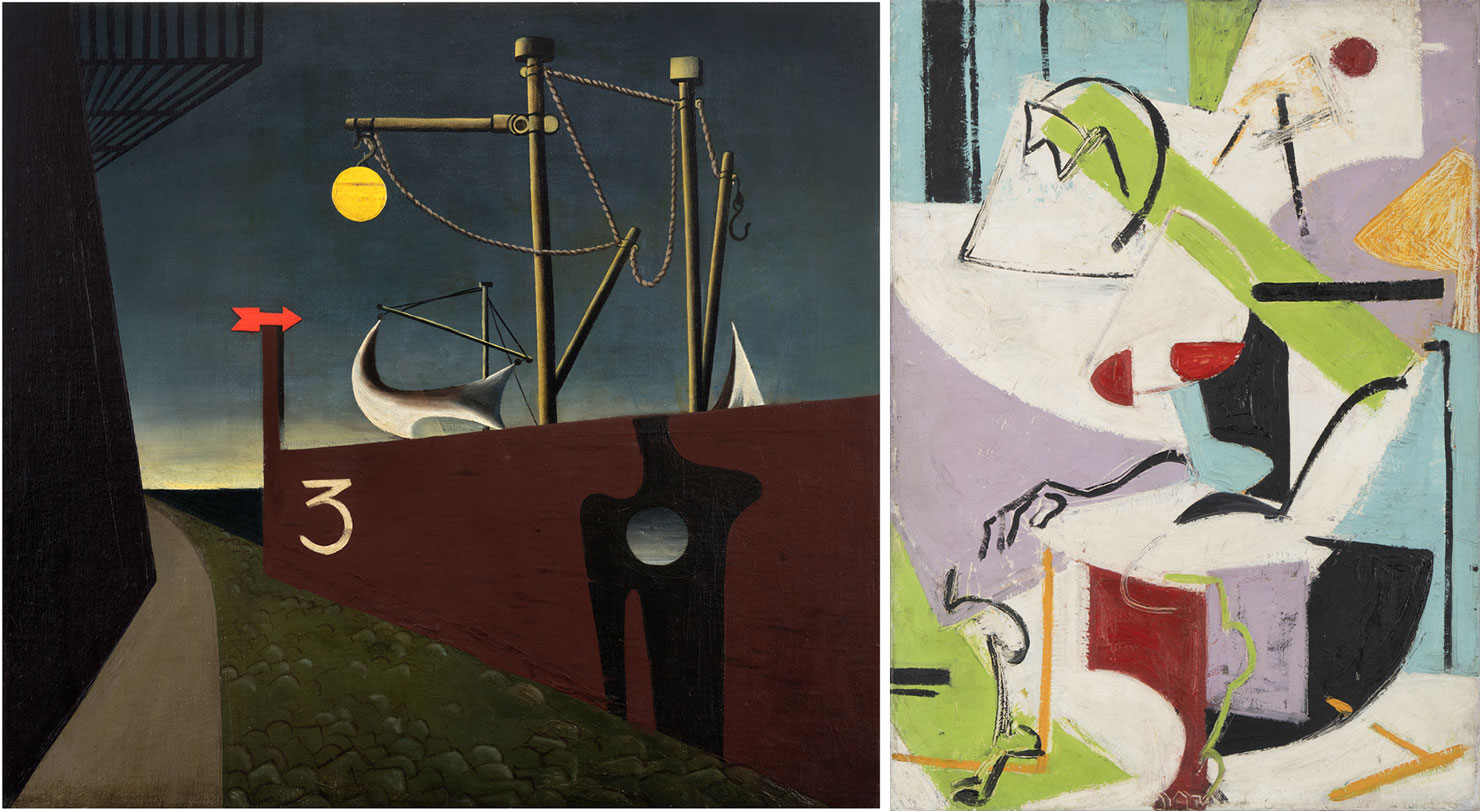

By Efi Michalarou

Lee Krasner was born to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. Krasner was the first in her family to be born in the United States, just nine months after her parents and older siblings emigrated due to growing anti-Semitic sentiment in Russia. At home in Brownsville, Brooklyn, the family spoke a mix of Yiddish, Russian, and English, though Krasner favored English. Krasner’s parents ran a grocery and fishmonger in East New York and often struggled to make ends meet. Her older brother Irving, to whom she was very close, read to her from classic Russian novels like Gogol and Dostoevsky. Though she was a naturalized citizen, Krasner felt connected to her parents’ homeland. Later in life, she often bristled at the suggestion that she was a fully American artist. At an early age, she decided that the arts-focused, all-girls Washington Irving High School in Manhattan was the only school she wanted to attend, as its arts focus was a rarity at the time. Krasner was initially denied entry to the school due to her Brooklyn residence, but she eventually managed to gain admission. Perhaps ironically, Krasner excelled in all classes except for art, but she passed because of her otherwise exceptional record. During high school, Krasner abandoned her given name “Lena” and took on the name “Lenore,” inspired by the Edgar Allen Poe character. After graduation, Krasner attended the Cooper Union, here she changed her name once again, this time to Lee: an Americanized (and, notably, androgynous) version of her given Russian name. Having attended two art-centric girls’ schools, the idea of being a woman artist was not remarkable to the young Krasner. It was not until she went to the National Academy of Design that she encountered resistance to her chosen career path. She was riled by the idea that women were sometimes kept from doing what the male artists were permitted to do at the traditionally-minded institution. 1929 was a notable year for Krasner. That year marked the opening of MoMA which exposed her to the Modernist style and the enormous possibility it represented. 1929 also marked the beginning of the Great Depression, which spelled disaster for many aspiring artists. Krasner joined the Works Projects Administration (WPA), which employed artists for various public art projects, including the many murals on which Krasner worked. It was on the WPA that she met critic Harold Rosenberg, who would later go on to write a seminal essay on the Abstract Expressionists, as well as many other artists. Krasner lived with Igor Pantuhoff, a painter of Russian origin and an alumni of the National Design Academy, for most of their ten-year relationship. However, Pantuhoff’s parents held anti-Semitic views of Krasner, and the two never married. In the late 1930s, Krasner took classes led by the expressionist painter and famed pedagogue Hans Hofmann. Krasner became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, a group formed in New York City in 1936 to promote and help the public appreciate abstract art. It was then that she met Pollock, moving in with him in 1941. The pair married in 1945, and the duties of promoting and managing the practical aspects of Pollock’s career fell to her. While Krasner generously embraced her new responsibilities, it meant her own career took a back seat to the increasingly famous Pollock. Krasner never stopped creating during her 11-year marriage to Pollock. Throughout their time together, Krasner struggled with his pronounced alcoholism and womanizing. When the couple relocated from Manhattan to the Springs, Long Island, in the late 1940s, and Krasner began her breakthrough “Little Imageseries” (1946-50), a body of work defined by the small size of the paintings and their repetitive, linear designs often in white pigment. Along with Newman, Krasner shared an interest in Jewish Mysticism, or Kabalah, which comes to light in these small canvases. Her traditional Jewish education and heritage shaped the process and look of this series in which she intuitively painted right to left, or the direction of Hebrew lettering and created Kabalistic symbols, in order to directly connect with her subconscious. Many modernists looked to other cultures, such as non-Western and tribal groups, for their artistic inspirations, whereas Krasner in fact was returning to her own cultural origins. Krasner possessed a lifelong admiration of Matisse’s work, and in the early 1950s began to experiment with collage, a technique that Matisse used late in his career. After a particularly frustrating day in the studio Krasner impetuously tore up her finished paintings, which she then later reassembled into constructions reminiscent of Cubism. Krasner’s 1955 exhibition of these works was positively received, prompting well-known and demanding critic Clement Greenberg to declare it one of the most important shows of the decade. The following year, Krasner began a large-scale Abstract Expressionist series called “Earth Green” (1956-59) after her husband’s death in a fatal car accident. Critics responded negatively to these works, which combined nature-inspired forms with a rhythmic, splattered technique, because they believed that the work was both derivative of Pollock’s and too decorative (a codeword for too feminine). In 1962, Krasner suffered an aneurism, which sidelined her artistic productivity for several years afterward due to ill health. In the following period, Krasner continued to work with her nature-forms in variety of ways, combining them with large areas of more solid color on her canvases (a choice inspired by Color Field Painting and Minimalism). In the late 1960s and 1970s, her work experienced a revival due to the women’s movement. In 1978, the exhibition “Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years” positioned Krasner in her rightful place alongside Pollock, de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb. Krasner’s experimental techniques and innovative use of color and scale were finally recognized in her first retrospective exhibition in October 1983 at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in Texas. Despite her poor health, Krasner was able to attend the exhibition, which subsequently traveled to San Francisco, California, Phoenix, Arizona, and Norfolk, Virginia. Unfortunately, Krasner died in June 1984 from internal bleeding due to diverticulitis and was never able to see her retrospective make its final stop at New York’s eminent Museum of Modern Art.

Lee Krasner was born to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. Krasner was the first in her family to be born in the United States, just nine months after her parents and older siblings emigrated due to growing anti-Semitic sentiment in Russia. At home in Brownsville, Brooklyn, the family spoke a mix of Yiddish, Russian, and English, though Krasner favored English. Krasner’s parents ran a grocery and fishmonger in East New York and often struggled to make ends meet. Her older brother Irving, to whom she was very close, read to her from classic Russian novels like Gogol and Dostoevsky. Though she was a naturalized citizen, Krasner felt connected to her parents’ homeland. Later in life, she often bristled at the suggestion that she was a fully American artist. At an early age, she decided that the arts-focused, all-girls Washington Irving High School in Manhattan was the only school she wanted to attend, as its arts focus was a rarity at the time. Krasner was initially denied entry to the school due to her Brooklyn residence, but she eventually managed to gain admission. Perhaps ironically, Krasner excelled in all classes except for art, but she passed because of her otherwise exceptional record. During high school, Krasner abandoned her given name “Lena” and took on the name “Lenore,” inspired by the Edgar Allen Poe character. After graduation, Krasner attended the Cooper Union, here she changed her name once again, this time to Lee: an Americanized (and, notably, androgynous) version of her given Russian name. Having attended two art-centric girls’ schools, the idea of being a woman artist was not remarkable to the young Krasner. It was not until she went to the National Academy of Design that she encountered resistance to her chosen career path. She was riled by the idea that women were sometimes kept from doing what the male artists were permitted to do at the traditionally-minded institution. 1929 was a notable year for Krasner. That year marked the opening of MoMA which exposed her to the Modernist style and the enormous possibility it represented. 1929 also marked the beginning of the Great Depression, which spelled disaster for many aspiring artists. Krasner joined the Works Projects Administration (WPA), which employed artists for various public art projects, including the many murals on which Krasner worked. It was on the WPA that she met critic Harold Rosenberg, who would later go on to write a seminal essay on the Abstract Expressionists, as well as many other artists. Krasner lived with Igor Pantuhoff, a painter of Russian origin and an alumni of the National Design Academy, for most of their ten-year relationship. However, Pantuhoff’s parents held anti-Semitic views of Krasner, and the two never married. In the late 1930s, Krasner took classes led by the expressionist painter and famed pedagogue Hans Hofmann. Krasner became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, a group formed in New York City in 1936 to promote and help the public appreciate abstract art. It was then that she met Pollock, moving in with him in 1941. The pair married in 1945, and the duties of promoting and managing the practical aspects of Pollock’s career fell to her. While Krasner generously embraced her new responsibilities, it meant her own career took a back seat to the increasingly famous Pollock. Krasner never stopped creating during her 11-year marriage to Pollock. Throughout their time together, Krasner struggled with his pronounced alcoholism and womanizing. When the couple relocated from Manhattan to the Springs, Long Island, in the late 1940s, and Krasner began her breakthrough “Little Imageseries” (1946-50), a body of work defined by the small size of the paintings and their repetitive, linear designs often in white pigment. Along with Newman, Krasner shared an interest in Jewish Mysticism, or Kabalah, which comes to light in these small canvases. Her traditional Jewish education and heritage shaped the process and look of this series in which she intuitively painted right to left, or the direction of Hebrew lettering and created Kabalistic symbols, in order to directly connect with her subconscious. Many modernists looked to other cultures, such as non-Western and tribal groups, for their artistic inspirations, whereas Krasner in fact was returning to her own cultural origins. Krasner possessed a lifelong admiration of Matisse’s work, and in the early 1950s began to experiment with collage, a technique that Matisse used late in his career. After a particularly frustrating day in the studio Krasner impetuously tore up her finished paintings, which she then later reassembled into constructions reminiscent of Cubism. Krasner’s 1955 exhibition of these works was positively received, prompting well-known and demanding critic Clement Greenberg to declare it one of the most important shows of the decade. The following year, Krasner began a large-scale Abstract Expressionist series called “Earth Green” (1956-59) after her husband’s death in a fatal car accident. Critics responded negatively to these works, which combined nature-inspired forms with a rhythmic, splattered technique, because they believed that the work was both derivative of Pollock’s and too decorative (a codeword for too feminine). In 1962, Krasner suffered an aneurism, which sidelined her artistic productivity for several years afterward due to ill health. In the following period, Krasner continued to work with her nature-forms in variety of ways, combining them with large areas of more solid color on her canvases (a choice inspired by Color Field Painting and Minimalism). In the late 1960s and 1970s, her work experienced a revival due to the women’s movement. In 1978, the exhibition “Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years” positioned Krasner in her rightful place alongside Pollock, de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb. Krasner’s experimental techniques and innovative use of color and scale were finally recognized in her first retrospective exhibition in October 1983 at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in Texas. Despite her poor health, Krasner was able to attend the exhibition, which subsequently traveled to San Francisco, California, Phoenix, Arizona, and Norfolk, Virginia. Unfortunately, Krasner died in June 1984 from internal bleeding due to diverticulitis and was never able to see her retrospective make its final stop at New York’s eminent Museum of Modern Art.