ART CITIES:Basel-Len Lye

Born in Christchurch, New Zealand (ΝΖ), Len Lye (is one of the most important experimental filmmakers of the period 1930-1960. Living first in New Zealand and Australia, then frorm1926 in London, and from 1944 in New York, he created a fascinating body of work that encompasses not just film but an artistic discipline, much of which, including his kinetic sculptures, has yet to be discovered.

Born in Christchurch, New Zealand (ΝΖ), Len Lye (is one of the most important experimental filmmakers of the period 1930-1960. Living first in New Zealand and Australia, then frorm1926 in London, and from 1944 in New York, he created a fascinating body of work that encompasses not just film but an artistic discipline, much of which, including his kinetic sculptures, has yet to be discovered.

By Efi Michalarou

Photo: Museurn Tinguely Archive

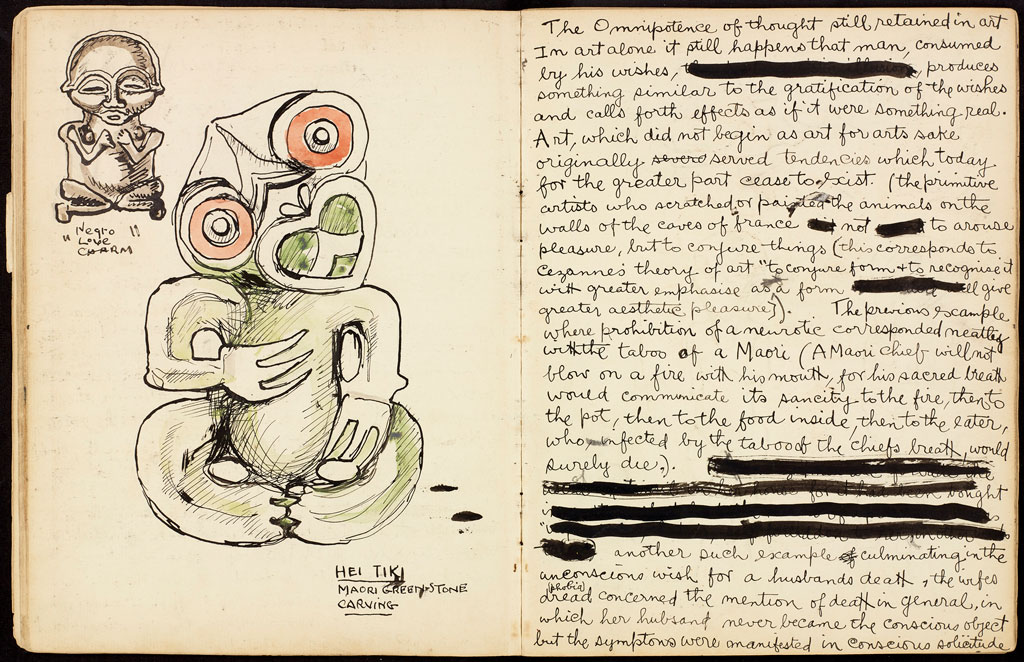

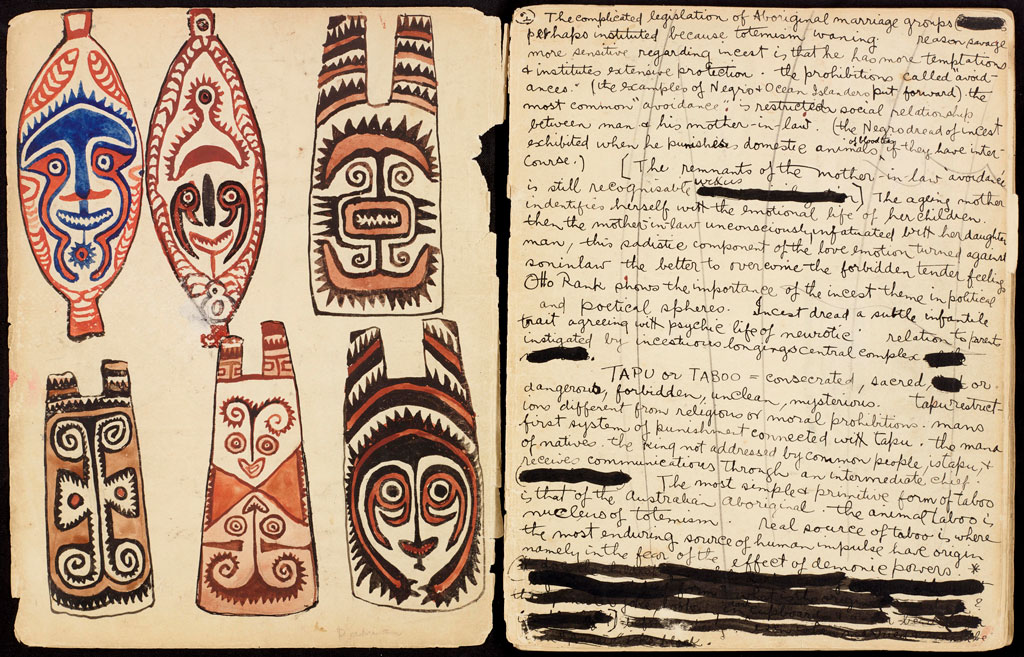

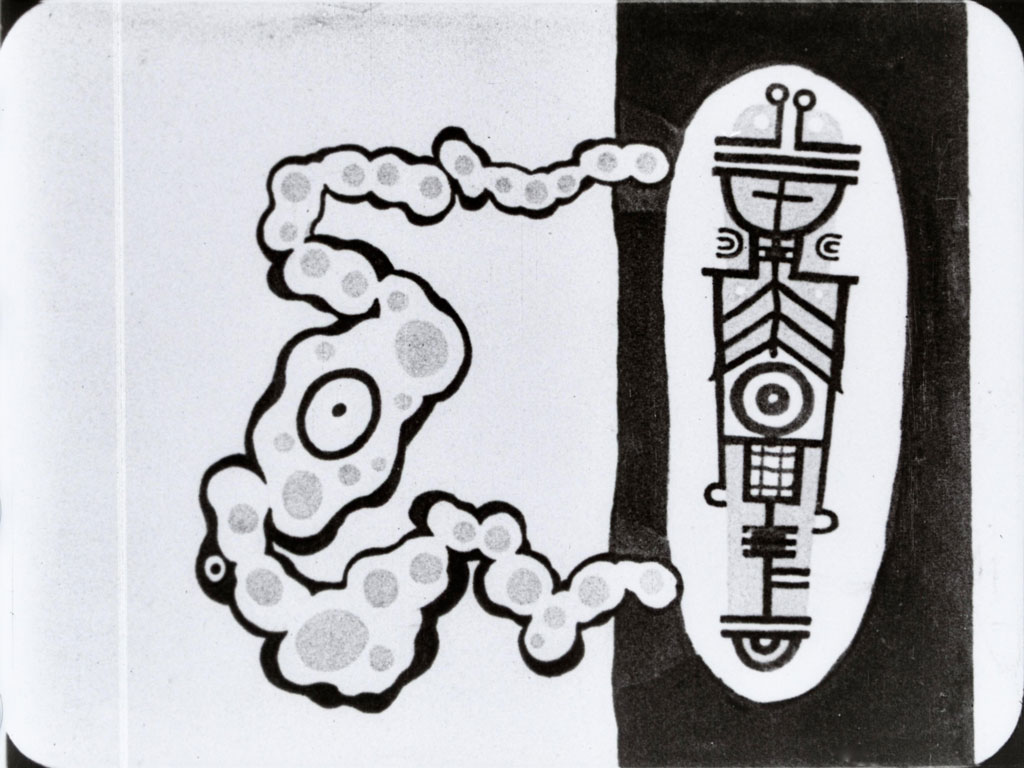

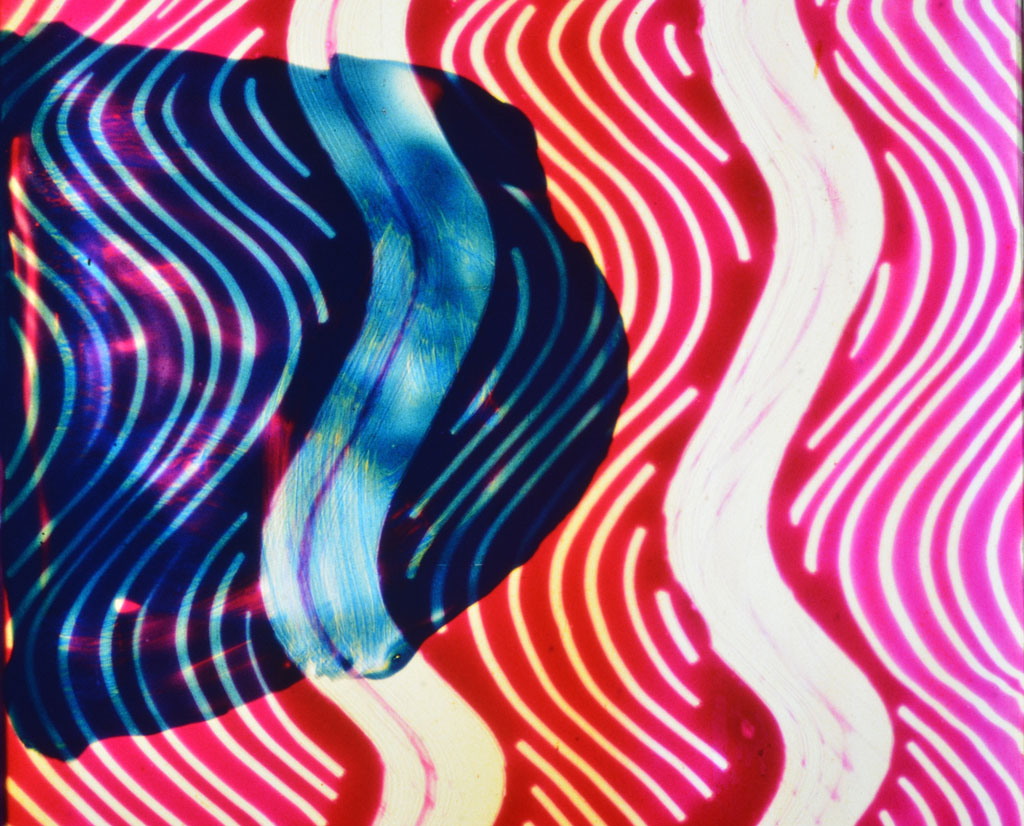

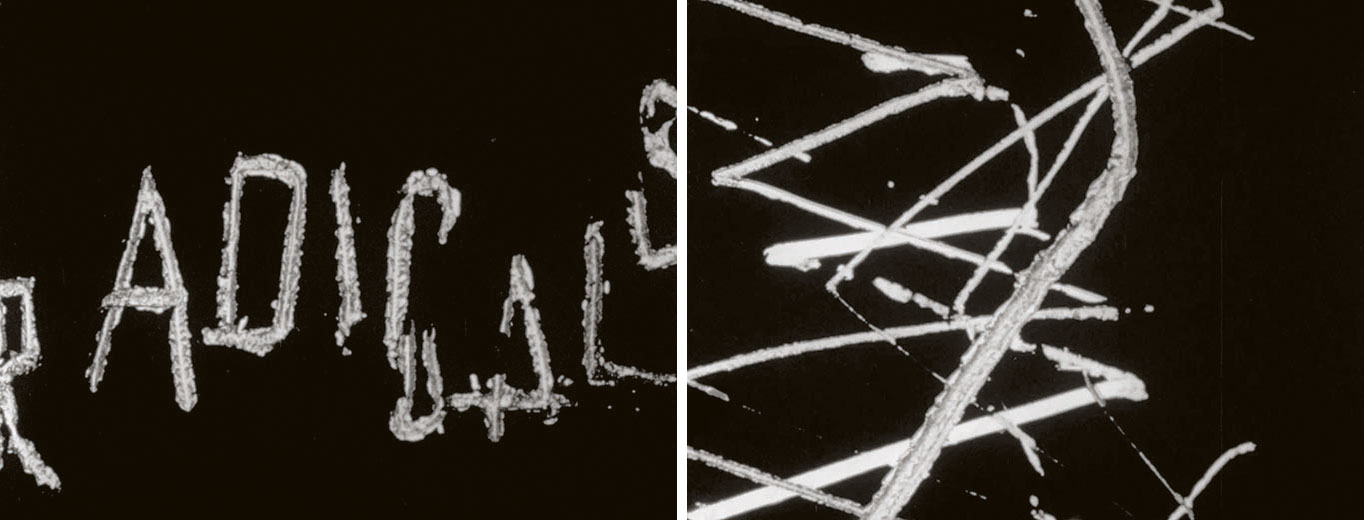

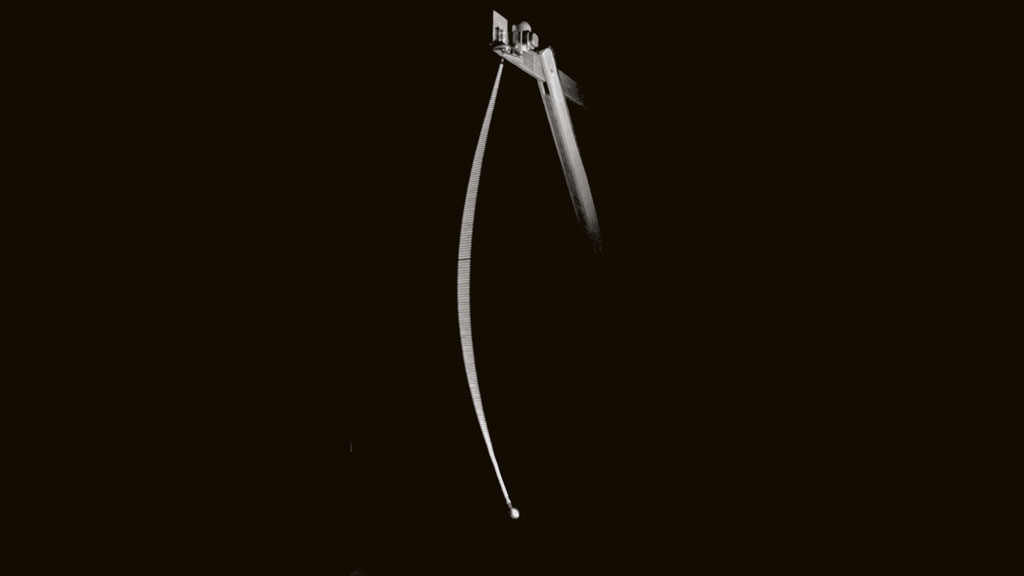

In the exhibition “Len Lye – Motion composeρ” at Museurn Tinguely, the full breadth of Lye’s oeuvre is be shown with a special focus on relations between different media. The museum visitors are invited to discover Lye’s universe with more than 100 artworks and to explore his life’s work through a variety of media including films, sketches and sculptures. The exhibition is complemented with a film program at the Stadtkino Basel presenting four films by and about the artist. Len Lye was born in 1901 into a family of modest means. After the early death of his father, he lived with his mother and brother at the home of his stepfather Ford Powell who worked as a lighthouse keeper in Cape Campbell. This was the time, he said, when he had his first experiences of light and movement – themes that would occupy him throughout his life. He described the moment when he found the motif of his art as follows: he was thinking about John Constable’s Cloud Study and about the way the painter imitated and conveyed movement: “All of a sudden it hit me – if there was such a thing as composing music, there could be such a thing as composing motion. After all, there are melodic figures, why can’t there be figures of motion?” He began drawing movements, in small notes and spontaneous doodles. At the beginning of the 1920s he spent several months in Samoa where he came into contact with the rich life of its indigenous people. During his years in Sydney (1922-26) he made the Totem and Taboo Sketchbook into which he transcribed Sigmund Freud’s text Totem and Taboo on the right-hand pages, juxtaposed with drawings of objects from various cultures (from Samoa, Africa, the Maori of his native New Zealand, the Australian Aborigines) and works by Russian Constructivists that struck him as related both aesthetically and in terms of content. His eye unobstructed by Eurocentrism, he created a work that was without parallel at the time, relating objects and cultures without any form of hierarchy or ranking. In 1926, Lye arrived in London and soon, besides paintings that often explored his subconscious and batiks that played with the formal idioms of foreign cultures, he made his first film, laying the foundations for his fame as an experimental filmmaker. 1929 saw the first screening of “Tusalava”, an animated film in which abstract figures and shapes relate to one another, becoming entangled and united. In the Surrealism-influenced circles in which Lye moved, this ten-minute film, accompanied by live music by Jack Ellitt (that has sadly been lost), made a big impact. In the mid-1930s, this was followed by Lye’s “direct films” for which he painted and wrote directly onto the celluloid, making a key contribution to the technique of camera-less film. “Α Color Box” (1935) was a colorful film with a soundtrack of Cuban dance music that advertised Britain’s post office. Other films followed and, through their use as advertising for various companies in cinemas, reached a broad audience. The combination of abstract color film and modern music was revolutionary and rightly earned Lye a reputation as the inventor of the music video. After World War ΙΙ, during which Lye made propaganda for the British, producing much admired films like “Kill or Be Killed” (1942), he lived in New York City, pursuing his career as an experimental filmmaker. In1947, he also made a series of photograms: portraits in which he applied the idea of camera -less film to still photography. One of the most radical films from his New York period is “Rhythm” (1957) in which the workings of an American car factory are presented, with a soundtrack of African drum music, as a dance of technology. In “Rhythm”, and even more in “Free Radicals“ (1958/1979), he used the technique of scratching into the emulsion of black leaders, giving the films a raw mood. At the end of the 1950s, Lye turned his attention to kinetic sculpture, quickly developing concepts for around 20 “Tangibles” as he called his sculptures driven by electrical motors, performing programmed sequences of movements based on simple principles like rotating a bunch of steel rods or shaking a sheet of steel. With these sculptures, he struck a chord at a time when people were looking for new art, for machines and movement. As early as 1961, he was able to show these works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York on the occasion of a lecture performance in which he explained and presented his ideas of programmed machine sculpture. Lye understood his sculptures as models that he wanted to realize on a larger scale. Because he lacked both the technical know-how and the financial means, most never moved beyond this project stage, but his will to up-scale was shown especially in the drawings for “Sun, Land and Sea” (1965) that only came close to realization years after his death in 1980. Lye’s role in the kinetic art of the 1960s should not be underestimated. His vision for using programmed machine sculpture to create a whole new kind of art paved the way for much that is now familiar and taken for granted – in the field of kinetic art, but above all in the fields of land art and installation where Lye played a pioneering role.

Info: Curator: Andres Pardey, Museurn Tinguely, Paul Sacher-Anlage 2, Basel, Duration: 23/10/19-26/1/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Sun 11:00-18:00, www.tinguely.ch