PHOTO:SITUATIONS-Deviant

SITUATIONS is an experimental exhibition format at Fotomuseum Winterthur that reacts dynamically to current photographic and cultural developments. A SITUATION may take the form of a photographic image, a video or a performance, an essay or quote aimed at an in-depth exploration of a topic. Numbered consecutively, SITUATIONS are presented as thematic clusters in the physical space and online.

SITUATIONS is an experimental exhibition format at Fotomuseum Winterthur that reacts dynamically to current photographic and cultural developments. A SITUATION may take the form of a photographic image, a video or a performance, an essay or quote aimed at an in-depth exploration of a topic. Numbered consecutively, SITUATIONS are presented as thematic clusters in the physical space and online.

By Dimitris Lempesis

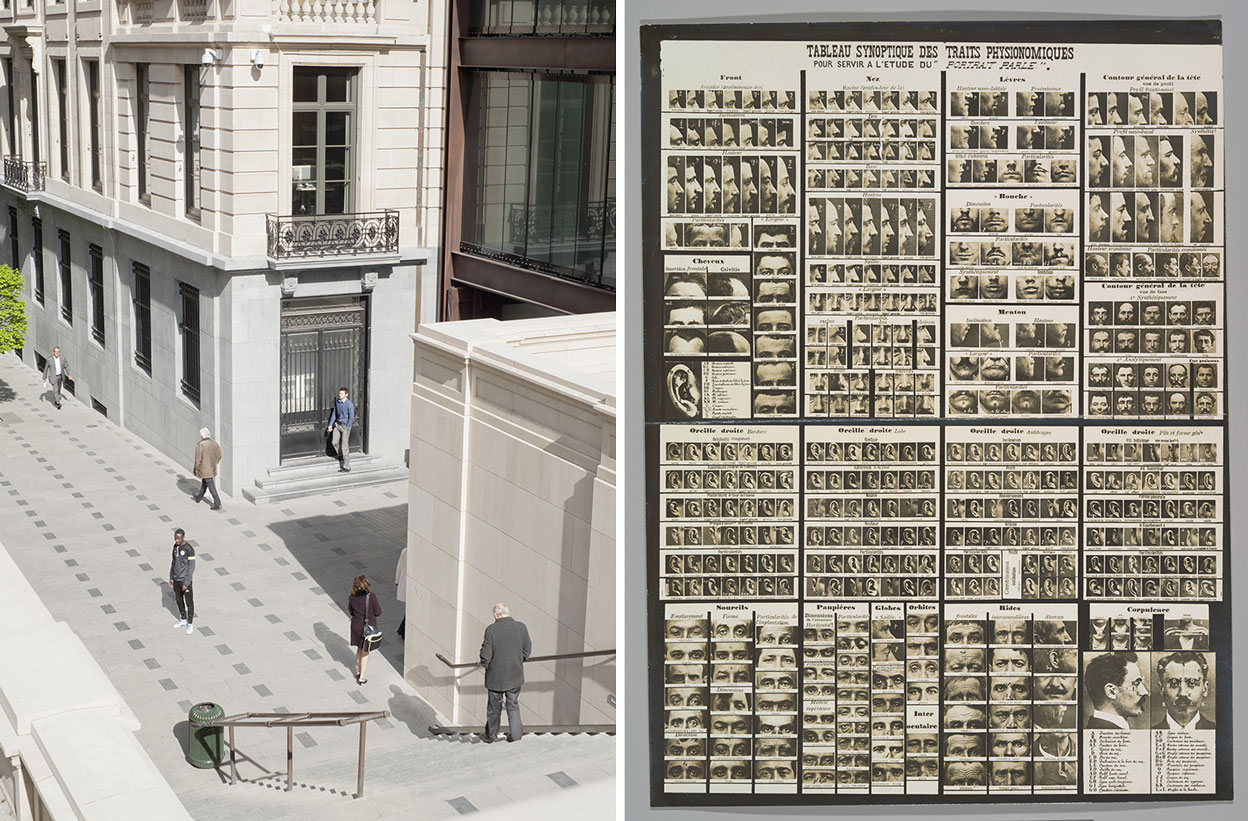

Photo: Fotomuseum Winterthur Archive

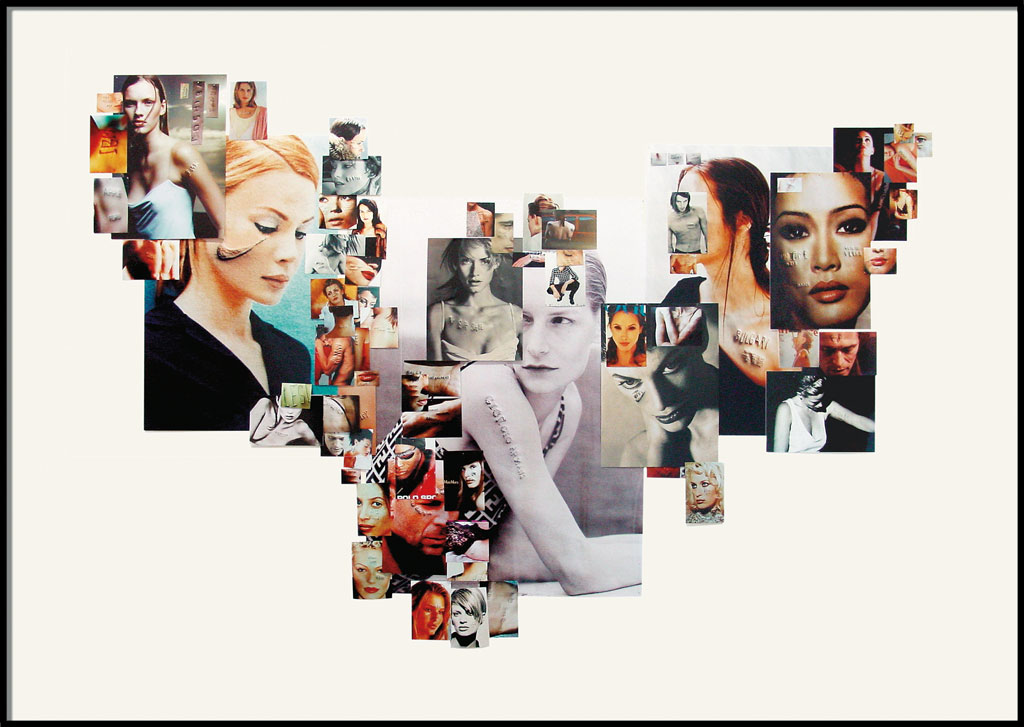

“Deviant” is the newest cluster as part of its ongoing exhibition format SITUATIONS. The artistic positions by Mitra Azar, Daniele Buetti, Esther Hovers, Simone C. Niquille, Carrie Mae Weems and Mushon Zer-Aviv examine the mechanisms of socio-cultural normalisation and deviation in the age of digital surveillance systems, algorithmic classification tools and preemptive technologies. The works by Mitra Azar, Daniele Buetti, Esther Hovers, Simone C. Niquille, Carrie Mae Weems and Mushon Zer-Aviv all revolve around the normative logics and effects of photographic images and the visualisation as well as reinforcement of (social) difference. Mitra Azar is an eclectic nomadic video-squatter and ARTthropologist with a background in aesthetic philosophy. Mitra admits to be haunted by images and by the relational-performative-philosophical aspect of engaging with them. The idea of border as fluid, flexible, amorphous entity and the political role of art and digital technologies within the frame of an aesthetic of crisis and of mass events have been the framework of his practice based research. In the last years, Mitra have been investigating crisis areas located both at geographical borders and during upraises and revolutions, focusing on offline/ online mass behaviors and politics of space mainly through the lens of visual anthropology, art, and media philosophy. Mitra have been field-researching in between filmmaking, media anthropology, tactical media and visual art for about 10 years, living as a nomad and working in some of the most critical area of the world. Mitra experienced prison in Iran during 2009 Green revolution and persuade a diplomat to smuggling out of the country the footage of his movie. He got captured in Alexandria by the military during the Egyptian Revolution – and went over night back to Cairo during his house arrest to hide and safe-copy his footage. He worked in China undercover on a movie about cyber-activism and internet censorship. He has crossed by feet around 20 of the most controversial borders of this planet and there managed to realize site-specific projects and interventions. Daniele Buetti explores fashion world, media codes, and our society’s obsession with beauty through a range of different media including photography, light-box installation, performance, and sculpture. After working for fashion editorials during the 90s, Buetti turned to fine arts. In his best-known series Looking for Love (1997-2000), Buetti modifies pictures of supermodels found in magazines or on the Internet by drawing brand symbols and ornaments just like scars or tattoos on the printed skin. Suddenly, the illusion we have of perfect beauty breaks down. More recently, Buetti’s work emphasizes on our obsession for fame as well as our relationship with the celebrity world, for example when he replaces famous people’s faces with mirrors to allow viewers to confront with their self-image. Simone C Niquille is a designer and researcher based in Amsterdam. Her studio Technoflesh investigates the representation of identity and the digitization of biomass in the networked space of appearance. She holds a BFA in Graphic Design from Rhode Island School of Design and a M.A. in Visual Strategies from the Sandberg Instituut Amsterdam. She teaches Design Research at ArtEZ University of the Arts Arnhem and is a 2016 Fellow of Het Nieuwe Instituut Rotterdam. Simone C Niquille is commissioned contributor to the Dutch Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. Her current work investigates standards of living and being embedded in parametric design processes. For her project “False Positives” (2015-16) Esther Hovers worked with intelligent surveillance system experts and based her project on a total of eight diagnosed “anomalies” in public space: Deviations from the usual behavioural norms, expressed through the body language and the movements of pedestrians. These deviations, tracked with visual technologies, are translated into data and fed into the algorithms of surveillance cameras. Intelligent surveillance systems reverse the temporal logic of surveillance: rather than just providing image material for the retrospective analysis of crimes, they are able to detect deviant, potentially criminal behaviour based on specific corporeal behaviours and can thus initiate an intervention even before a crime has occurred. Hovers’ photographs are imbued with the analytical gaze of the camera, while the tension between documentation and staging raises a discomforting concern: when is the preemptive intervention, i.e. the active and anticipatory intervention in a potentially imminent event, justified—and at what point do these technologies start producing their own reality? Carrie Mae Weems is known for creating installations that combine photography, audio, and text to examine many facets of contemporary American life. Weems, who is probably best known as a photographer, initially studied modern dance. She received her first camera at age 21. In 1978 she began her first photographic project, called “Environmental Profits”, which focused on life in Portland. That same year she started her first major series, “Family Pictures and Stories”, completed about five years later. Her landmark “Kitchen Table Series” (1990) uses images and screenprinted text panels to offer a polyvalent portrayal of the modern black woman. Featuring Weems as the recurring subject of staged photographs at a single table, either by herself or with others, the series centers on commonly overlooked or discredited roles and is intended to reflect the collective subjectivity of every woman, resonating across racial, temporal, and socioeconomic boundaries. In “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried” (1995–96), Weems appropriated images from the 19th and early 20th Centuries featuring black subjects, including J. T. Zealy’s ethnographic studies of enslaved people, and other objectifying portraits that reinforce racist tropes. Through her selection and presentation of these images, Weems interrogates the intentions of the white photographers who produced and disseminated them. She tinted each picture a deep red and overlaid on them lyrical texts that outline and lament a long-running history of exploitation and subjugation, articulating the myriad ways that photographic representation has been utilized to perpetuate dehumanizing stereotypes. “The Normalizing Machine” (2018), an interactive installation developed by Mushon Zer-Aviv in collaboration with the software developers Dan Stavy and Eran Weissenstern, deals with visual notions of “normality” and the ways in which bias is inscribed into and reinforced by algorithms and machine learning systems. While being captured on camera, visitors have to decide from a collection of previously photographed visitor portraits which ones seem more “normal” to them. The data sets assembled in this way are evaluated in order to generate an algorithmic image of “normality”. Zer-Aviv thus tracks face recognition techniques of the 21st century back to practices of facial measurement misused for propagandistic purposes under the Nazi regime as well as to the forensic image practices emerging as early as the 19th century. The Normalizing Machine examines how we perceive “normality” today, questioning whether we can do so beyond subjective categories—and the role of photographic technologies as supposedly “objective” techniques with regard to mechanisms of normalisation.

Info: Fotomuseum Winterthur, Grüzenstrasse 44 + 45, Winterthur, Duration: 19/10/19-23/2/20, Days & hours: Tue & Thu-sun 11:00-18:00, Wed 11:00-20:00, www.fotomuseum.ch