ART-PRESENTATION: California Dreams,Part II

With artworks and historical objects from numerous Californian and European lenders the exhibition “California Dreams” draws, for the first time in Europe, a many-faceted portrait of the city of San Francisco over four centuries. It touches upon important global issues of our time, especially those of migration and displacement. The exhibition celebrates San Francisco as a place whose pluralistic identity is constantly being renegotiated to this day (Part I).

With artworks and historical objects from numerous Californian and European lenders the exhibition “California Dreams” draws, for the first time in Europe, a many-faceted portrait of the city of San Francisco over four centuries. It touches upon important global issues of our time, especially those of migration and displacement. The exhibition celebrates San Francisco as a place whose pluralistic identity is constantly being renegotiated to this day (Part I).

By Dimitris Lempesis

Photo: Bundeskunsthalle Archive

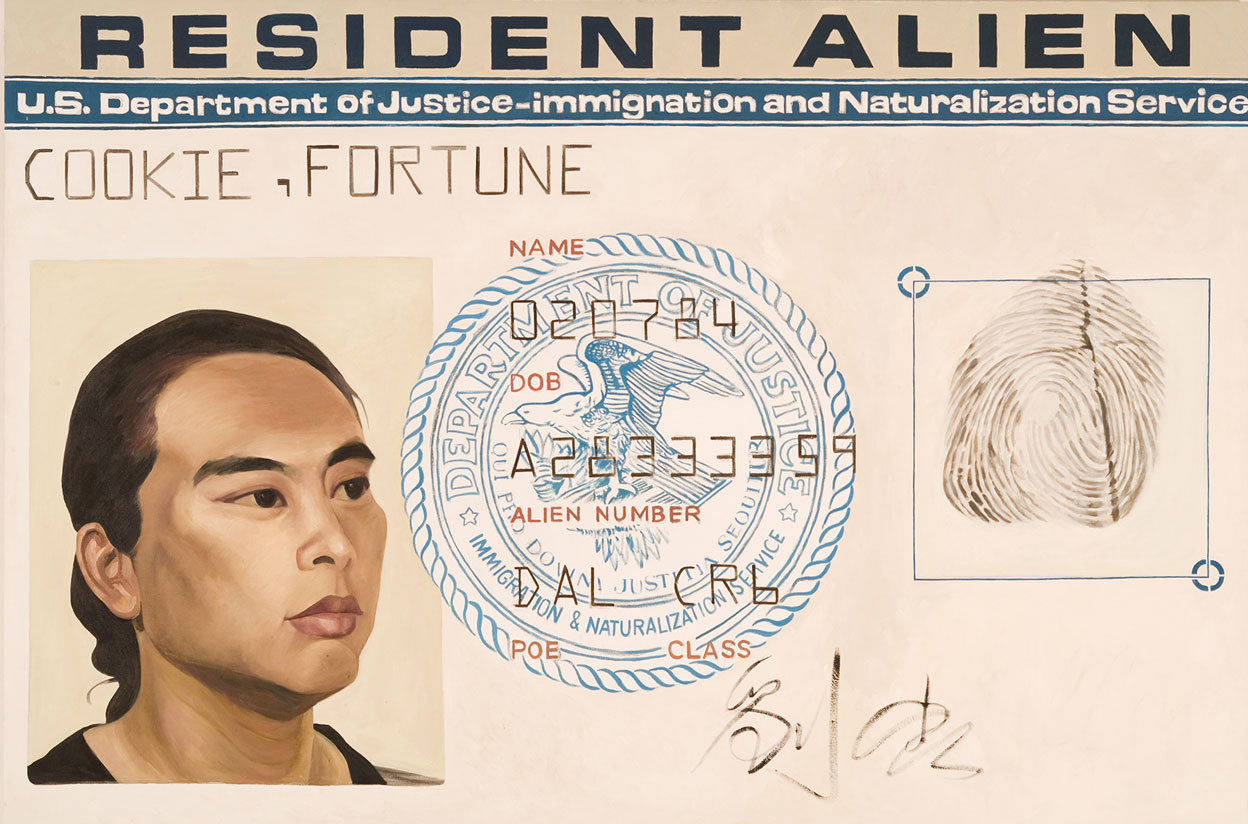

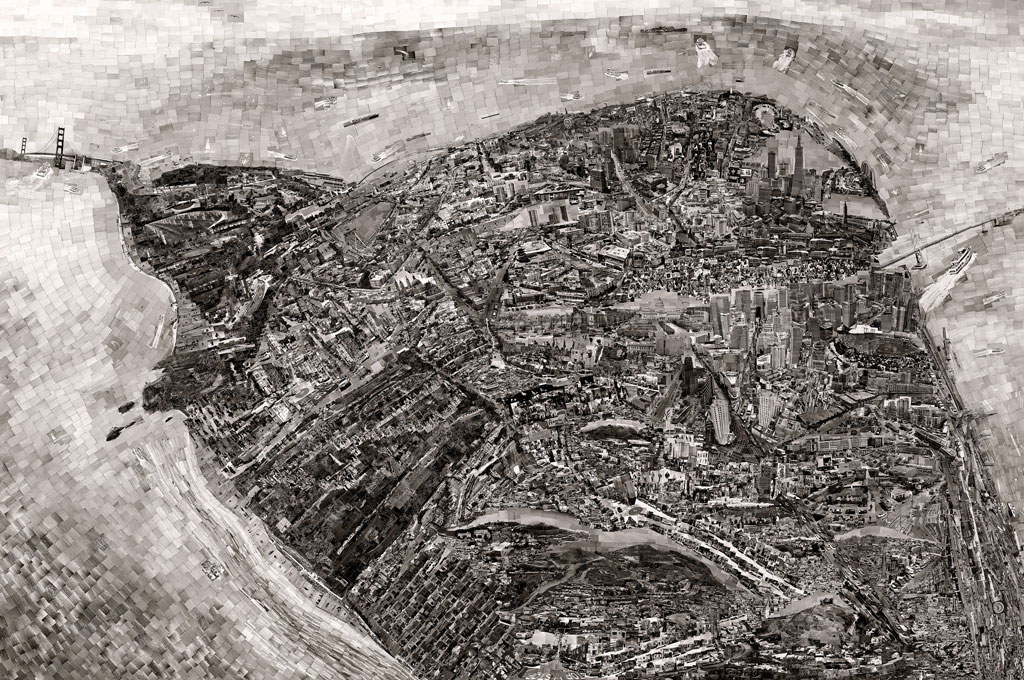

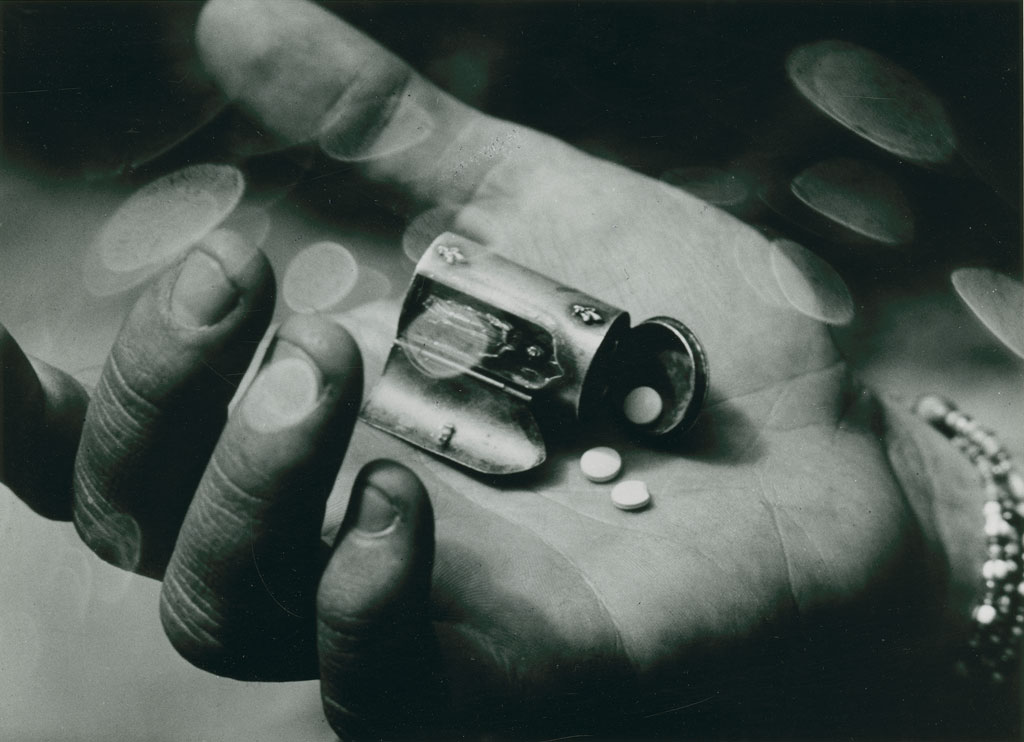

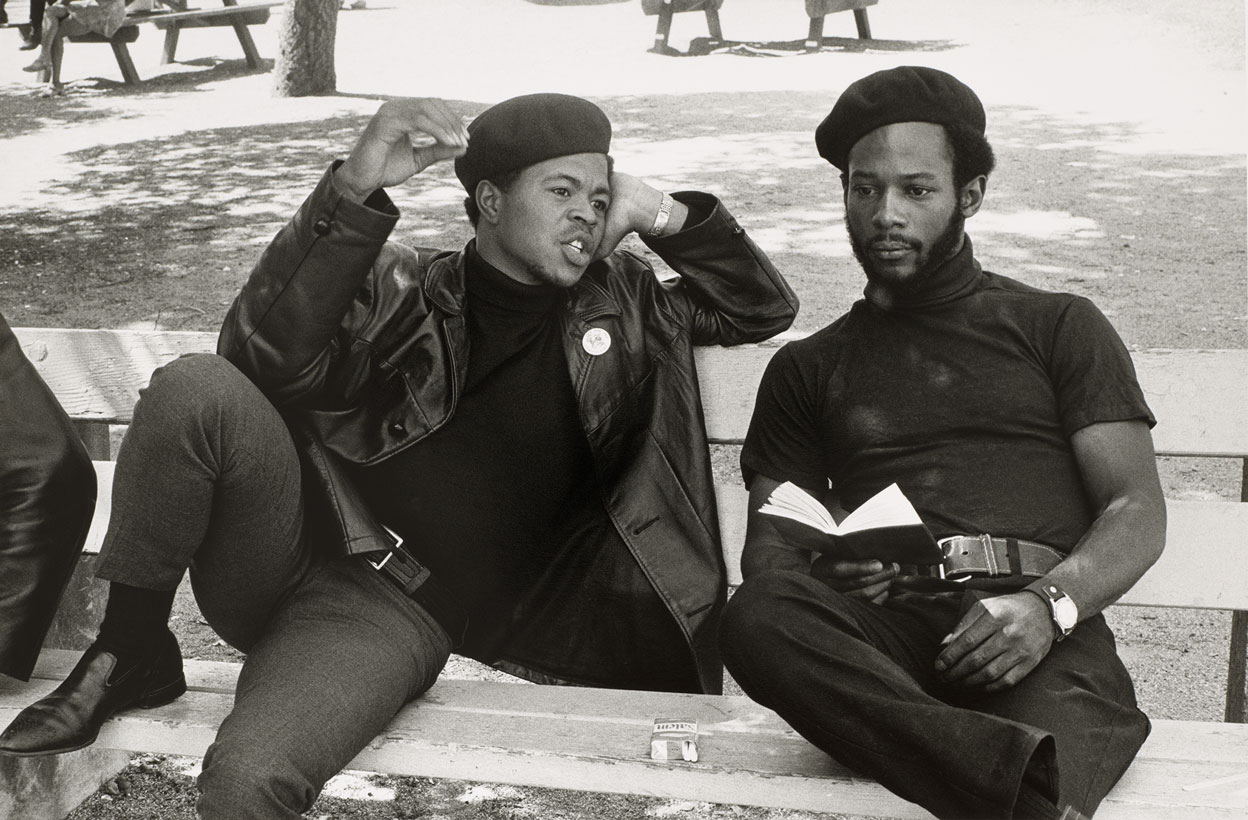

As places of longing, California and San Francisco in particular have always stood for the dreams of a “better life”: dreams of prosperity and abundance, of other (at times utopian) social orders, innovative life styles, creative artistic perspectives, and new technological horizons. Both the Asian-Pacific region in the west and Europe in the east have had a lasting impact on San Francisco. The exhibition “California Dreams” dedicated to the dreams and realities of the people of the San Francisco Bay Area, past and present inn three sections: GLOBAL DREAMS AND INDIVIDUAL HOPES: California was home to over 70 indigenous peoples, who tapped the country’s rich natural resources as fishermen, hunters, and gatherers. After the first landfalls in the course of the European voyages of exploration of the 16th Century, the territory was nominally claimed for both the Spanish and English crowns. Often covered in mist, however, the bay of present-day San Francisco was discovered only in the 18th Century. Founded in 1776 under the reign of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the mission San Francisco de Asís, the military base (Presidio) set up for its protection, and the small port town of Yerba Buena formed the nucleus of today’s San Francisco. Farther north on the Pacific coast, Russian fur traders established Colony Ross as the southernmost outpost of their possessions in North America in 1812. The Mexican War of Independence put an end to Spanish colonial rule in 1821 and made California a Mexican province until 1848, when it became part of the United States after the U.S. victory in the Mexican-American War – just a few days after the first discovery of gold. For the indigenous peoples of California, these colonial and national power struggles resulted in forced conversion to Christianity, economic exploitation, the loss of their land base, and deaths from introduced diseases and arbitrary persecution. While up to the mid-nineteenth century it was mainly imperial visions that attempted to direct California’s fate, the gold rush of 1849 attracted global migration flows of an unprecedented scale to the Golden Gate. Hundreds of thousands of people arrived in search of a better life, of gold and wealth, or of new economic opportunities, and San Francisco developed into a metropolis in record time. The cityscape was shaped by immigrants from Europe and Asia, whose cultural diversity, however, cannot obscure the ethnic and social hierarchies prevailing from the outset. Already in the 1850s, 80 percent of personal property and real estate in San Francisco were in the hands of less than five percent of its White population. DREAMS OF SURVIVAL AND THE AMERICAN MAINSTREAM: San Francisco had become the leading economic and cultural metropolis on the American West Coast when on 18 April 1906 one of the worst natural disasters in the history of the United States hit the city: a magnitude 7.8 earthquake destroyed a large portion of the city and left hundreds of thousands of its inhabitants homeless. The geographic location of San Francisco near the San Andreas Fault – the boundary between two tectonic plates – still makes the threat of an earthquake an everyday danger. Devastating forest fires and man-made environmental damages since the gold rush further threaten the ever-expanding population of the San Francisco Bay Area. Especially the indigenous populations had fought for their physical and cultural survival since the invasion of the Europeans. Ishi (c. 1860–1916), “the last Yahi” was “discovered” in 1911, after hiding for many years from White society. He was taken to the Museum of Anthropology of the University of California, where Alfred Kroeber with Ishi’s help reconstructed Yahi language and customs. His fate is reminiscent of the expropriation, displacement, and extermination of the indigenous peoples of California, but it also illustrates their persistent cultural self-assertion. Irrespective of the outbreak of World War I, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915 not only celebrated the completion of the Panama Canal in the year before, but also the rebuilding of the city and the unbroken economic optimism of its citizens. Despite the war and the Great Depression, the confidence in technological progress and in consumer society based on religious-conservative values had remained part of the American self-image and found renewed expression in the World Fair of 1939, which not least celebrated the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge (1937). However, the internment of some 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans during the World War II – an easily forgotten chapter in American history – illustrates all too clearly that the “land of opportunity” was not equally open to everyone. COUNTERCULTURES AND VIRTUAL DREAMS: The political movements, alternative lifestyles, artistic innovations, and not least the technological revolutions originating in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 20th and 21st centuries had and continue to have a global impact on politics and society. After World War II the artists of the Beat Generation broke with the social norms heretofore regarded as valid. After New York, San Francisco became their creative center in the 1950s. With their themes of sexual liberation, their interest in Far Eastern religions, and their experimental use of drugs they provided path-breaking stimuli for subsequent generations. Hardly any other protest movement has achieved a comparable global radiance as the Hippie Movement of the 1960s, which refused to accept the traditional ideals of prosperity and bourgeois constraints. Accompanied by student revolts at the University in Berkeley and the Native American occupation of Alcatraz, the Hippie Movement found its socio-political focus in the protest against the Vietnam War and its cultural culmination in the legendary “Summer of Love” of 1967. Nostalgically kept alive, it continues to shape the image of San Francisco until today. Founded in Oakland, the Black Panther Party called for resistance against the social oppression of the Black population and reflected the African-American self-confidence that had grown during the civil rights movement. Since the 1950s, decisive impulses were also provided by the movement for the rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender people (“Queer Liberation”), which demanded the social recognition and legalization of homosexuality on a national and international level. As the Mecca of the IT and high-tech industry, Silicon Valley in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area has become a new magnet for immigration. The global utopian ideas sold from here close the circle of the exhibition and once again demonstrate the close proximity of dream and nightmare: environmental pollution, underpayment, and homelessness are the other side of the visionary billion dollar business.

Info: Curators: Sylvia S. Kasprycki and Henriette Pleiger, Bundeskunsthalle (The Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany), Helmut-Kohl-Allee 4, Bonn, Duration: 12/9/19-12/1/20, Days & Hours: Tue-Wed 10:00-21:00, Thu-Sun 10:00-19:00, www.bundeskunsthalle.de