TRACES: Sophie Calle

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Sophie Calle (9/10/1953- ), one of France’s leading Conceptual artists. Her work is distinguished by its use of arbitrary sets of constraints, and evokes the French literary movement of the 1960s known as Oulipo. Her work frequently depicts human vulnerability, and examines identity and intimacy. She is recognized for her detective-like ability to follow strangers and investigate their private lives. Her photographic work often includes panels of text of her own writing. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

Today is the occasion to bear in mind Sophie Calle (9/10/1953- ), one of France’s leading Conceptual artists. Her work is distinguished by its use of arbitrary sets of constraints, and evokes the French literary movement of the 1960s known as Oulipo. Her work frequently depicts human vulnerability, and examines identity and intimacy. She is recognized for her detective-like ability to follow strangers and investigate their private lives. Her photographic work often includes panels of text of her own writing. This column is a tribute to artists, living or dead, who have left their mark in Contemporary Art. Through documents or interviews, starting with: moments and memories, we reveal out from the past-unknown sides of big personalities, who left their indelible traces in time and history…

By Efi Michalarou

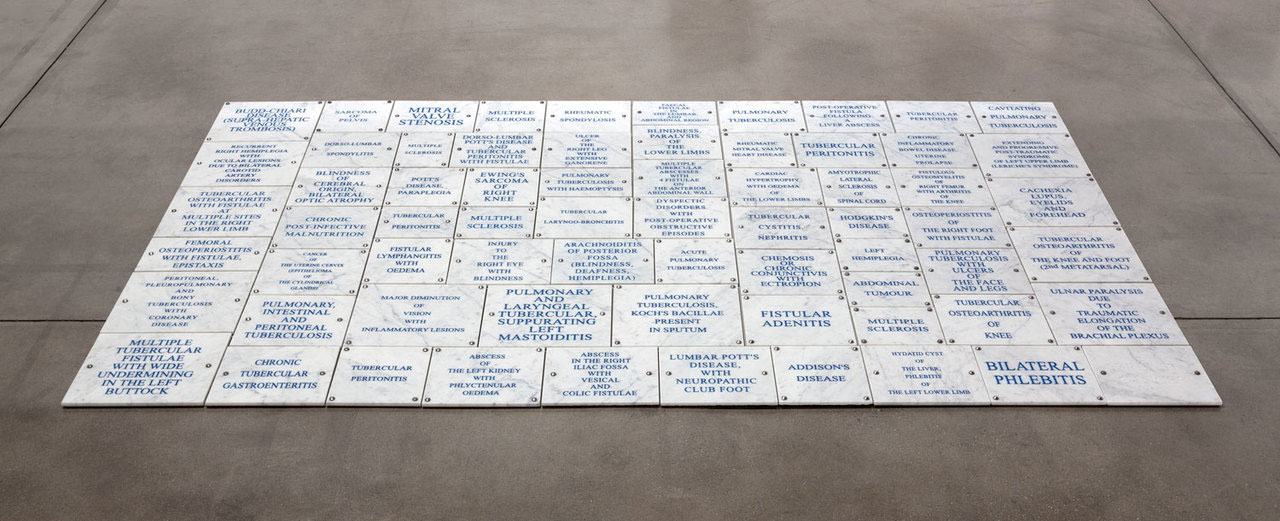

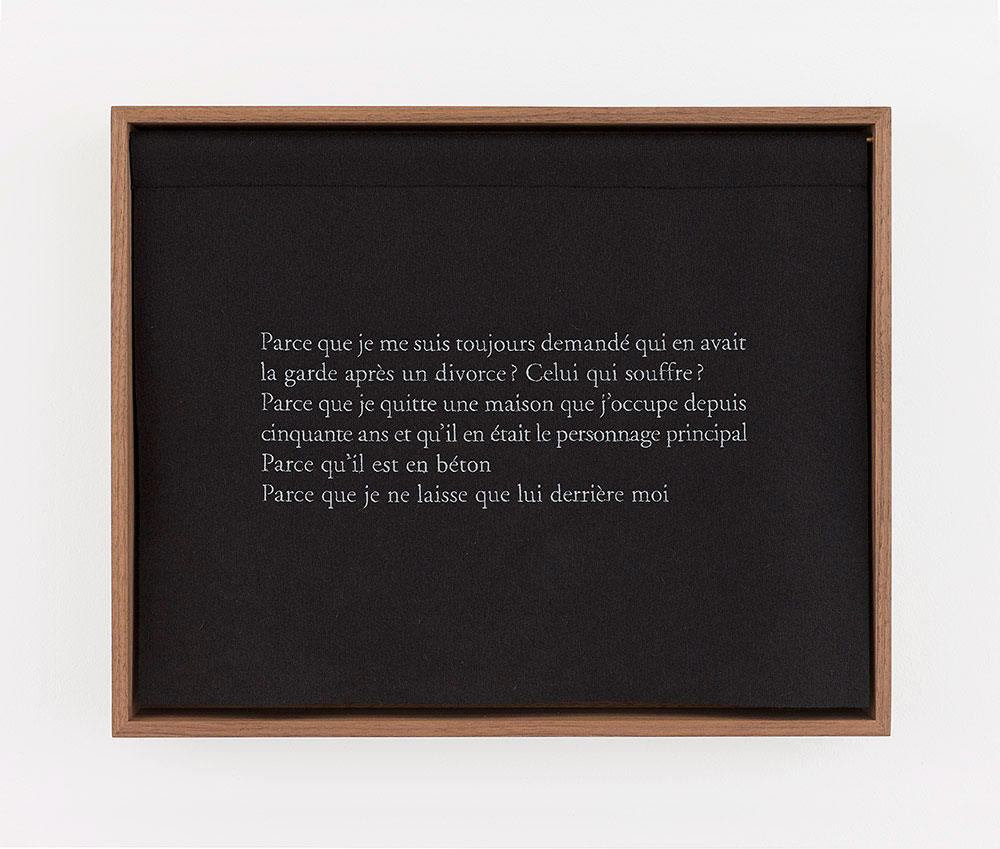

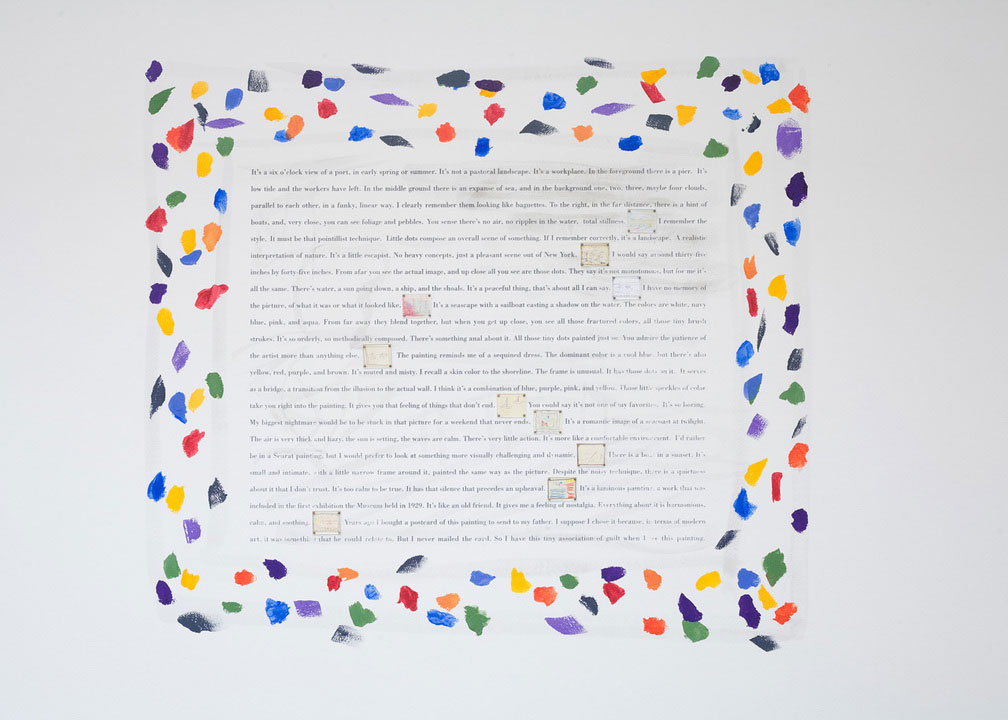

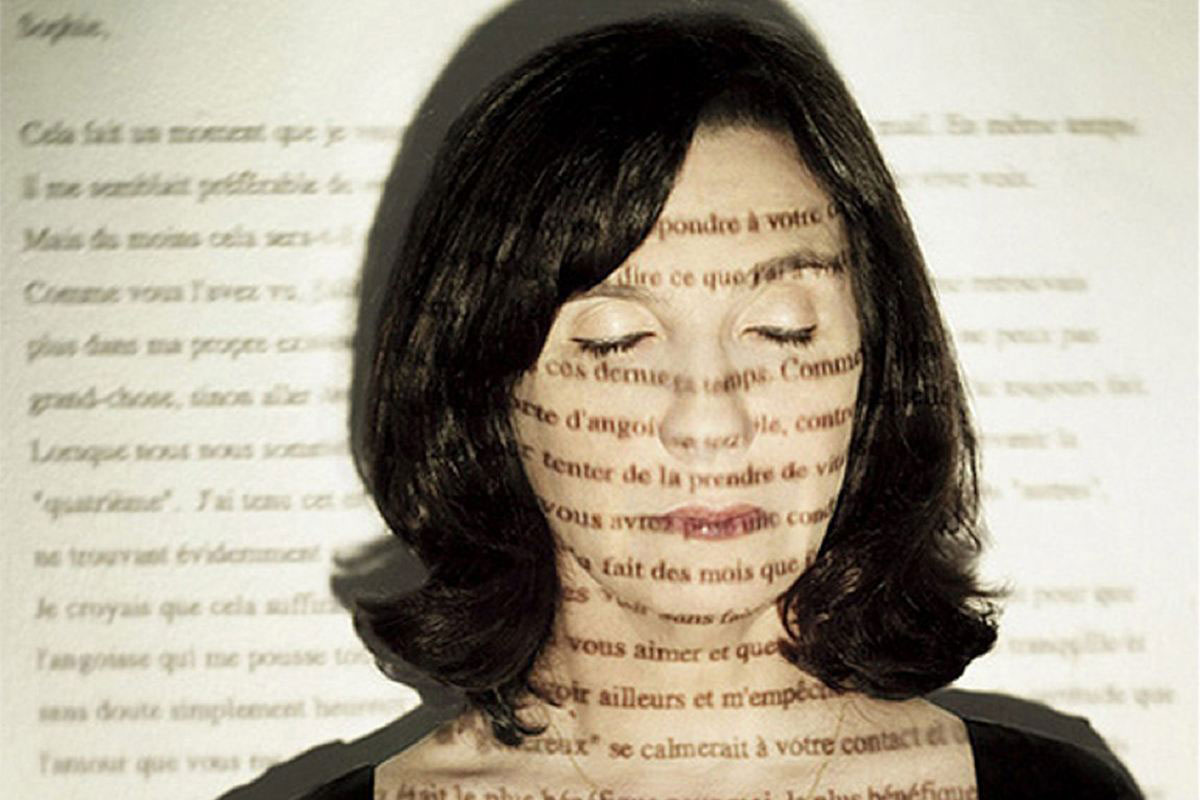

Sophie Calle was born into an intellectual and creative household in 1 Paris, where she experienced an unconventional childhood. Her oncologist father, Robert Calle, was a renowned art collector and former director of the Nimes’ Carré d’Art, a contemporary art museum. Her mother, Monique Sindler, was a book critic and press attaché, later described by Calle as “the wildest mother, who was always center stage.” In fact, she would later become a huge subject of her daughter’s work, as in the installation “Rachel, Monique” (2014) which was a tribute to the life and loves of her mother, featuring a video of the final moments of her life. Instead of attending art school, Calle studied for a diploma under the postmodernist thinker Jean Baudrillard. She later claimed that he had faked her qualification in order to help her skip studying in lieu of travel – travel that would only be funded by her father as a reward for academic success. After she finished school, Calle spent time in China, Mexico, and the United States. In California, she became interested in photography, learning to use photographic equipment and associated rudimentary techniques. At the age of 26, she arrived back in her home city of Paris and decided to attend photography classes. Her attendance of the classes was short lived after the first lesson failed to thrill her. Nevertheless, she was influenced by the work of Duane Michals, an American photographer who combined images and text, and whose work her father collected. This influence emerged as Calle began to formulate her own artistic practice with photography and installation, combining photos, texts, and videos to weave narratives of private experience. Brushing off the label of artist, Calle described her projects often as “private games”, saying, “I did not think about becoming an artist when I began. I did not consider what I was doing as art”. Much of her work carried, instead, a socio-anthropological vein, in which she would come up with an idea or question, formulate a set of rules or constraints for which she might go about exploring it, then set about on a road toward discovery. Oftentimes these “games” would spotlight and provoke ideas about intimacy, privacy, social engagement, interrelationship, absence, and presence. Calle’s first major work was entitled “The Sleepers” (1979). The project arose from a chance request by one of her friends who asked if she could sleep in Calle’s bed. This inspired the artist to ask 29 people, both friends and strangers, to spend eight hours in her bed while she photographed them, asked them questions, and made notes. “The Sleepers” was first shown in 1980 at the Biennale des Jeunes and was composed of the photographs and textual descriptions written in a detached anthropological tone, a modus operandi that would become the basis of much of Calle’s artistic practice. During the time she spent reacquainting herself with Paris upon returning from her travels, Calle’s artistic practice developed. She began to construct instances and engagements that explored human vulnerability. She began to spend time following strangers and recording their movements, even to the extreme of following one unsuspecting French man all the way from Paris to Venice, all the while building up a dossier of images and notes about his travels. Calle also took on the role of a stripper in a club in the Pigalle district of Paris, which resulted in the work “The Striptease” (1979). The piece was comprised of a book of photographs of the adult Sophie stripping alongside cards her parents had received from friends when Sophie was born. The work was made against the wishes of Calle’s father and her relationship with him continues to be both touching and distant. After her mother died, Calle took her jewels to the North Pole where she buried them in a ceremony. Suite venitienne” (1980) is one of Calle’s earliest key works. ln it she secretly follows a man (Henry Β.) she barely knows around Venice; she uses the numerous photographs she took, accompanied with diary-like texts, to describe not just the methods of her surveillance but also her own feelings. lt demonstrates the fusion of investigative methods, fictional constructs and scenes from real life, as well as the construction of the ego, that is so characteristic of her work. One of Calle’s first projects to generate public controversy was “Address Book” (1983). The French daily newspaper Libération invited her to publish a series of 28 articles. Having recently found an address book on the street (which she photocopied and returned to its owner), she decided to call some of the telephone numbers in the book and speak with the people about its owner. To the transcripts of these conversations, Calle added photographs of the man’s favorite activities, creating a portrait of a man she never met, by way of his acquaintances. Another of Calle’s noteworthy projects is titled “The Blind” (1986), for which she interviewed blind people, and asked them to define beauty. Their responses were accompanied by her photographic interpretation of their ideas of beauty, and portraits of the interviewees. In 1996, Calle asked Israelis and Palestinians from Jerusalem to take her to public places that became part of their private sphere, exploring how one’s personal story can create an intimacy with a place. Inspired by the eruv, the Jewish law that permits to turn a public space into a private area by surrounding it with wires, making it possible to carry objects during the Sabbath, the Erouv de Jérusalem is exposed at Paris’s Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme. The same year, Calle released a film titled “No Sex Last Night” which she created in collaboration with American photographer Gregory Shephard. The film documents their road trip across America, which ends in a wedding chapel in Las Vegas. Rather than following the genre conventions of a road trip or a romance, the film is designed to document the result of a man and woman who barely knew each other, embarking on an intimate journey together. In 1999 Calle exhibited the installation “Appointment” especially conceived for the Freud Museum in London, working with the ideas of her private desires. In “Room with a View” (2002), Calle spent the night in a bed installed at the top of the Eiffel Tower. She invited people to come to her and read her bedtime stories in order to keep her awake through the night. The same year, Calle had her first one-woman show, a retrospective, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. At the 2007 Venice Biennale, Calle showed her piece “Take Care of Yourself”, named after the last line of the email her ex sent her. Calle asked friends, acquaintances, and recommended women of all ages, including a parrot and a hand puppet, to interpret the break-up e-mail and presented the results in the French pavilion. ln her video work “Voίr la mer” (2011), Calle conveys the moment when people see the sea for the first time. She chose people who live in Istanbul, a city surrounded by the sea. For whatever the reason these people had never seen the sea, Sophie Calle invites them to do so. With their eyes covered, these people – men and women, young and old – are led down to the beach and filmed as they see the sea for the first time. What do they feel? We can only imagine, perhaps with the help of our own memories of seeing the sea for the first time, but with an inkling that this quiet moment may well change how they see the world.

Sophie Calle was born into an intellectual and creative household in 1 Paris, where she experienced an unconventional childhood. Her oncologist father, Robert Calle, was a renowned art collector and former director of the Nimes’ Carré d’Art, a contemporary art museum. Her mother, Monique Sindler, was a book critic and press attaché, later described by Calle as “the wildest mother, who was always center stage.” In fact, she would later become a huge subject of her daughter’s work, as in the installation “Rachel, Monique” (2014) which was a tribute to the life and loves of her mother, featuring a video of the final moments of her life. Instead of attending art school, Calle studied for a diploma under the postmodernist thinker Jean Baudrillard. She later claimed that he had faked her qualification in order to help her skip studying in lieu of travel – travel that would only be funded by her father as a reward for academic success. After she finished school, Calle spent time in China, Mexico, and the United States. In California, she became interested in photography, learning to use photographic equipment and associated rudimentary techniques. At the age of 26, she arrived back in her home city of Paris and decided to attend photography classes. Her attendance of the classes was short lived after the first lesson failed to thrill her. Nevertheless, she was influenced by the work of Duane Michals, an American photographer who combined images and text, and whose work her father collected. This influence emerged as Calle began to formulate her own artistic practice with photography and installation, combining photos, texts, and videos to weave narratives of private experience. Brushing off the label of artist, Calle described her projects often as “private games”, saying, “I did not think about becoming an artist when I began. I did not consider what I was doing as art”. Much of her work carried, instead, a socio-anthropological vein, in which she would come up with an idea or question, formulate a set of rules or constraints for which she might go about exploring it, then set about on a road toward discovery. Oftentimes these “games” would spotlight and provoke ideas about intimacy, privacy, social engagement, interrelationship, absence, and presence. Calle’s first major work was entitled “The Sleepers” (1979). The project arose from a chance request by one of her friends who asked if she could sleep in Calle’s bed. This inspired the artist to ask 29 people, both friends and strangers, to spend eight hours in her bed while she photographed them, asked them questions, and made notes. “The Sleepers” was first shown in 1980 at the Biennale des Jeunes and was composed of the photographs and textual descriptions written in a detached anthropological tone, a modus operandi that would become the basis of much of Calle’s artistic practice. During the time she spent reacquainting herself with Paris upon returning from her travels, Calle’s artistic practice developed. She began to construct instances and engagements that explored human vulnerability. She began to spend time following strangers and recording their movements, even to the extreme of following one unsuspecting French man all the way from Paris to Venice, all the while building up a dossier of images and notes about his travels. Calle also took on the role of a stripper in a club in the Pigalle district of Paris, which resulted in the work “The Striptease” (1979). The piece was comprised of a book of photographs of the adult Sophie stripping alongside cards her parents had received from friends when Sophie was born. The work was made against the wishes of Calle’s father and her relationship with him continues to be both touching and distant. After her mother died, Calle took her jewels to the North Pole where she buried them in a ceremony. Suite venitienne” (1980) is one of Calle’s earliest key works. ln it she secretly follows a man (Henry Β.) she barely knows around Venice; she uses the numerous photographs she took, accompanied with diary-like texts, to describe not just the methods of her surveillance but also her own feelings. lt demonstrates the fusion of investigative methods, fictional constructs and scenes from real life, as well as the construction of the ego, that is so characteristic of her work. One of Calle’s first projects to generate public controversy was “Address Book” (1983). The French daily newspaper Libération invited her to publish a series of 28 articles. Having recently found an address book on the street (which she photocopied and returned to its owner), she decided to call some of the telephone numbers in the book and speak with the people about its owner. To the transcripts of these conversations, Calle added photographs of the man’s favorite activities, creating a portrait of a man she never met, by way of his acquaintances. Another of Calle’s noteworthy projects is titled “The Blind” (1986), for which she interviewed blind people, and asked them to define beauty. Their responses were accompanied by her photographic interpretation of their ideas of beauty, and portraits of the interviewees. In 1996, Calle asked Israelis and Palestinians from Jerusalem to take her to public places that became part of their private sphere, exploring how one’s personal story can create an intimacy with a place. Inspired by the eruv, the Jewish law that permits to turn a public space into a private area by surrounding it with wires, making it possible to carry objects during the Sabbath, the Erouv de Jérusalem is exposed at Paris’s Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme. The same year, Calle released a film titled “No Sex Last Night” which she created in collaboration with American photographer Gregory Shephard. The film documents their road trip across America, which ends in a wedding chapel in Las Vegas. Rather than following the genre conventions of a road trip or a romance, the film is designed to document the result of a man and woman who barely knew each other, embarking on an intimate journey together. In 1999 Calle exhibited the installation “Appointment” especially conceived for the Freud Museum in London, working with the ideas of her private desires. In “Room with a View” (2002), Calle spent the night in a bed installed at the top of the Eiffel Tower. She invited people to come to her and read her bedtime stories in order to keep her awake through the night. The same year, Calle had her first one-woman show, a retrospective, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. At the 2007 Venice Biennale, Calle showed her piece “Take Care of Yourself”, named after the last line of the email her ex sent her. Calle asked friends, acquaintances, and recommended women of all ages, including a parrot and a hand puppet, to interpret the break-up e-mail and presented the results in the French pavilion. ln her video work “Voίr la mer” (2011), Calle conveys the moment when people see the sea for the first time. She chose people who live in Istanbul, a city surrounded by the sea. For whatever the reason these people had never seen the sea, Sophie Calle invites them to do so. With their eyes covered, these people – men and women, young and old – are led down to the beach and filmed as they see the sea for the first time. What do they feel? We can only imagine, perhaps with the help of our own memories of seeing the sea for the first time, but with an inkling that this quiet moment may well change how they see the world.